- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Kharkiv's Underground Schools Protect Kids from Russian Bombs as Classes Resume

Despite relentless Russian aggression, Ukraine’s school year began on schedule on Monday, September 2, with 2 million students returning to classrooms. Since the 2022 invasion, Russia damaged nearly 3,800 schools, with 365 reduced to ruins, reported Ukrainian Human Rights Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets.

Ukrainian society has adapted in the face of Russia’s persistent aerial threats. President Zelenskyy reported that while 2 million students have resumed in-person classes, another 1 million are participating in a dual-format educational program across more than 10,500 schools.

Underground learning in Kharkiv

“Mom, when will I finally go to school?" asks Lev, a third-grader who spent the last year studying underground at the "University" station in the Kharkiv metro. His mother, Lilia, has heard this question nearly every day in the week leading up to the new school year.

This September, Lev moved from the metro to a Kharkiv school basement equipped with a certified radiation-proof shelter. While Lev is excited to see his teacher and classmates, many parents remain wary, as they haven’t seen the shelter yet. Nearly half of the parents oppose the move, but with no alternatives, they’ll have to overcome their fears—unlike their children, who seem unfazed.

In Kharkiv, 53,000 students are currently attending school, with another 50,000 studying online from outside the city. Most continue with online learning as in previous wartime years, but about 5,000 in Kharkiv and 13,000 in the region will attend classes in a mixed mode—part online, part in underground spaces. Mayor Ihor Terekhov says that fully in-person classes are nearly nonexistent, with a few first-grade classes attending metro schools four days a week, all in two shifts.

What are the options?

Kharkiv parents, given the limited availability of places, have three alternatives to online learning.

The most popular option, introduced last year, is the "metro school." Full classes are held 10 meters underground across six metro stations, utilizing service rooms, corridors, and balconies. A total of 3,500 students attend these classes offline each day, reported Olha Demenko, Director of Kharkiv’s Department of Education.

"It will never be the same as before the war because we have an evil, treacherous, and cruel neighbor,” she said. “We started teaching in the metro last school year. Now, we're expanding to six metro stations, where about 3,500 children will study.”

The second option is certified shelters in regular Kharkiv schools, though only two are currently available. Soviet-era school basements aren’t sufficient for missile or airstrike protection. Since 2023, the government and local authorities have started building and upgrading shelters, but this isn’t feasible everywhere, and the costs are nearly as high as building new schools, slowing progress. While only two shelters are ready, officials say more are close to completion.

The third option is new underground schools. The first, built in Kharkiv's KhTZ district (named after the Kharkiv Tractor Plant), was designed for 900 students but will now accommodate 1,100. Three more are under construction across the city. In the Kharkiv region, six are being built, with funding secured for 14 more, according to Oleh Synehubov, head of the Kharkiv Regional Military Administration. The first completed school, located six meters underground at a municipal lyceum in KhTZ, looks just like a regular school.

"The underground school at Lyceum No. 88 was built to meet all modern safety requirements,” said Demenko. “It has a powerful ventilation system that provides both heating and cooling, along with a fire alarm system and video surveillance—everything required by safety standards. It includes 20 full classrooms, a resource room for psychological relief, and a versatile hall that can be transformed by combining or separating three classrooms. From May to July, the school already functioned as a center for the National Multi-Subject Test and postgraduate entrance exams, ensuring future specialists from Kharkiv could take these tests in safe conditions."

Children will be transported to the underground school by bus.

"We've finalized the transport details, with about 20 bus routes serving these locations,” Demenko explained. “If you live nearby, you walk; if you're farther away, you'll be bused. We've easily adapted the logistics from last summer's metro school to the new underground sites.”

A new era of education

"Today, we’re welcoming a large number of children—1,100 students—to the underground school,” said Valentyna Pukhliy, the principal of Kharkiv's first underground school, adding that it is "the brightest day in the last three years" for the institution.

“We’re thrilled that children can study in person again, as distance learning simply can't match the quality of face-to-face education. Direct communication between parents, children, and teachers yields the best results. Today, we warmly welcome the students back, undeterred by the explosions in Kharkiv. You can see the joy on everyone’s faces as they reunite.”

Elementary students attend in the first shift, while older students attend in the second. All underground locations offer only three to four lessons daily, limited by space and the need to run two shifts due to high demand. Priority is given to first-graders and elementary students. High school students in Kharkiv haven’t attended in-person classes for nearly five years—two years due to the COVID-19 pandemic and three years of Russia’s full-scale war.

"Socialization is vital for elementary school children—and for everyone—because it helps develop communication skills, discover talents, and build leadership and organizational abilities,” said Demenko. “It’s also psychologically crucial. That’s why we prioritize first-graders and elementary students. I also want to highlight that since January 2024, we’ve been working with five-year-olds preparing for school. They attend metro school classes on Saturdays and Sundays. The metro school is never empty: five days a week, it’s a school, and on weekends, it transforms into a preschool for school preparation."

Challenges and plans

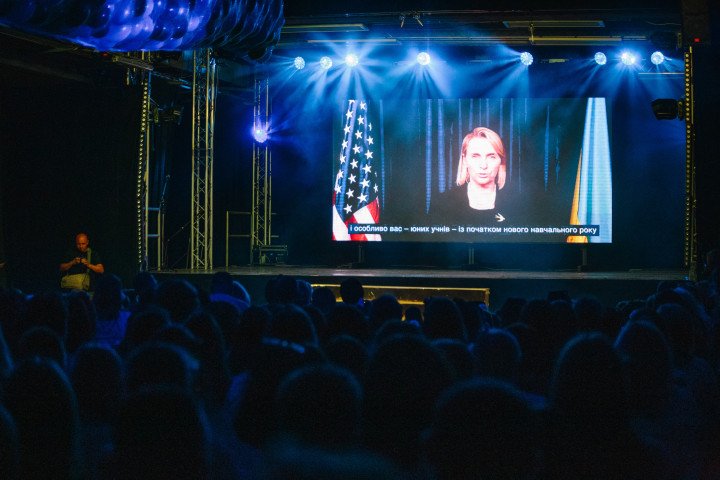

Kharkiv’s first underground school was built with municipal funds, costing 58 million UAH without equipment, said Mayor Terekhov. International aid, including from USAID, is helping to equip classrooms. The total cost, including equipment and landscaping, will reach 70-75 million UAH ($1.7-1.8 million). High construction costs and lack of state funding have slowed progress, meaning only 10% of Kharkiv’s students can attend in-person classes this year.

"We’re building three schools at our own expense, with municipal budget funds,” said Terekhov. “Two will accommodate 900 students each in two shifts, like the existing school. The third, in a remote area of Kharkiv, will serve 150 students. All three are expected to be ready by the late fall.”

Kharkiv will continue building underground schools, said Terakhov, but with current funding, it will take years.

“All 50,000 students could attend underground schools, but it requires more money, time, and project planning,” he said.

Kharkiv's underground school designs have been adopted in Zaporizhzhia, where similar schools are being built due to the ongoing Russian threat.

"Zaporizhzhia visited us, and we provided the project documentation,” Terekhov shared. “They're now constructing an underground school. This model is crucial in areas under constant attack where regular schooling isn't possible.”

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-7f50738271c122a9b5e663cb80703dd6.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)