- Category

- Opinion

What Does “Forward” Mean When Russia Is at War? The Art World’s Soviet Propaganda Fetish

How long will art spaces keep turning the symbols of violent power into trendy visuals, stripping them of the destruction they represent, while platforming Russians who stay silent even as Russians bomb cities under those very slogans?

When you enter the Art Basel Unlimited section , you’re greeted by a strange pairing: an installation reminiscent of a circus, and on the left side of it, two 6x6 meter paintings by Russian artist Erik Bulatov. His works assert the same word in red (orange?) and black:

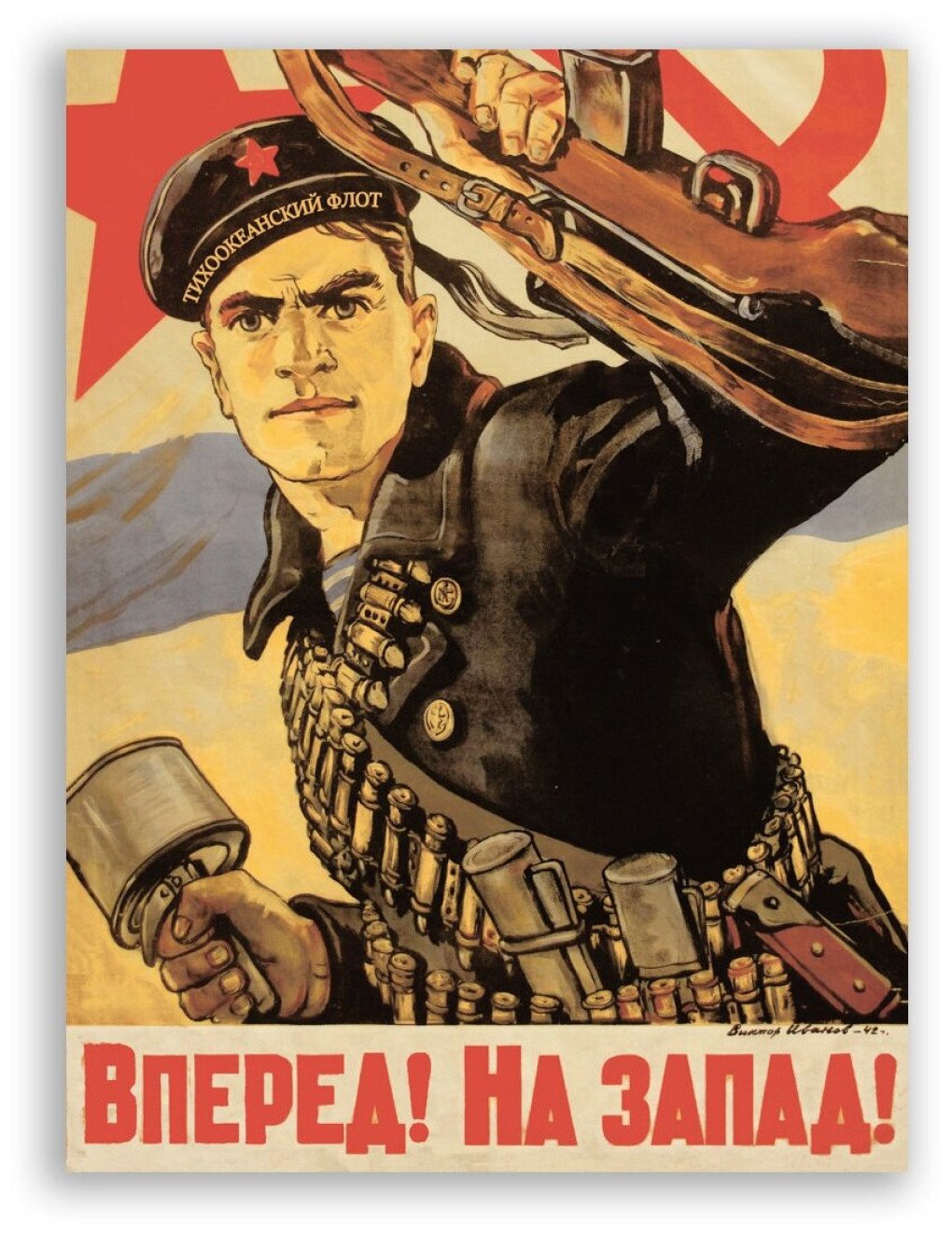

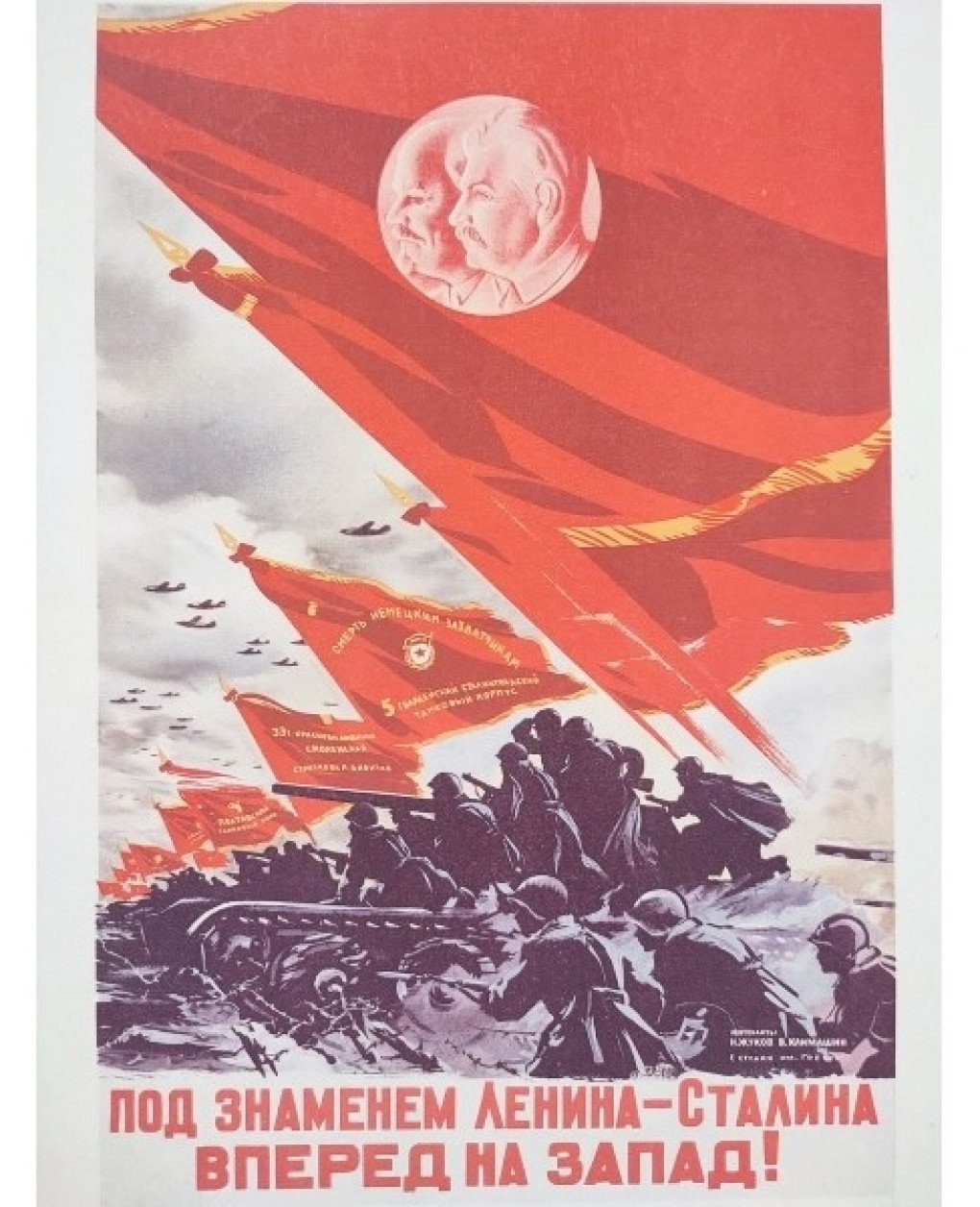

ВПЕРЁД — “Forward” / “Go ahead.” [russian lang.]

The description of the artwork states:

“In the Soviet world, this word was a slogan of the Communist Party: People were used to hearing or seeing it everywhere. Fascinated by the size and power of the graphics, the viewer is drawn in, then blocked and pushed back.”

Since its debut in 1970, Art Basel has become the premier platform for Modern and contemporary art. With annual art shows on three continents—Europe, North America, and Asia—it is the only art show with such global reach.

Interestingly enough, here, in Basel, Switzerland, the curator assumes we will be fascinated by the size and power of the graphics that revive the Soviet world.

The description continues:

“Unlike a superficial reading, and in opposition to a propaganda slogan, these paintings invite us to reflect.”

Having seen “ВПЕРЕД!” not in the historical books, but in the news, I perform an undesirable superficial reading of the work and subsequently skip the phase of fascination.

It tells us these paintings aren’t propaganda, but a call for “reflection.”

So—let’s reflect.

When "forward" leaves only death behind

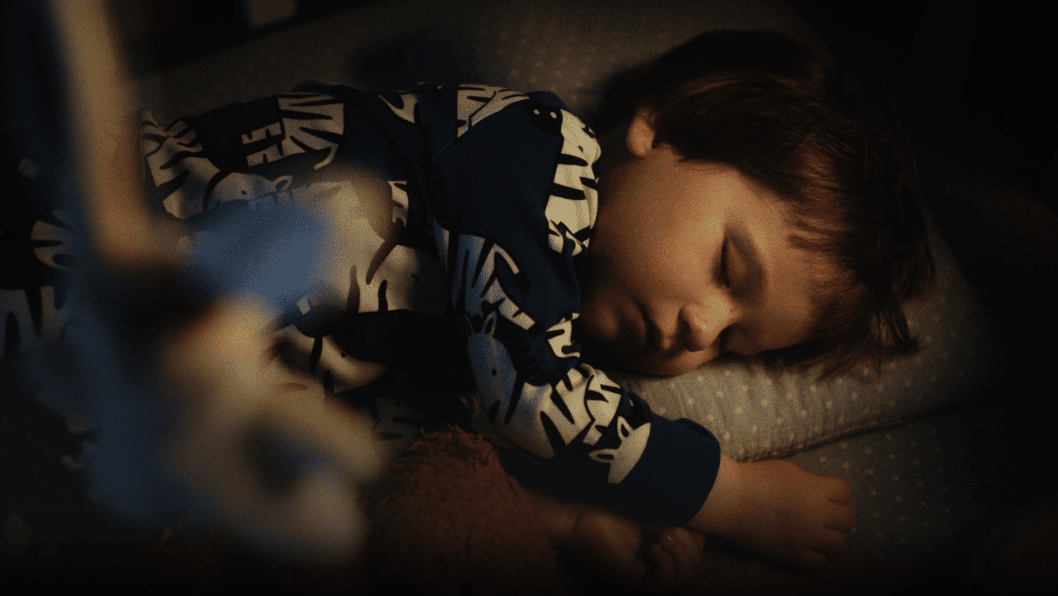

On the day Art Basel opened, Russia launched over 450 aerial attacks on Ukraine.

In Kyiv alone, over 130 people were injured, and more than 20 killed. And the first words 88,000 visitors saw walking into the Unlimited section confidently said:

ВПЕРЁД.

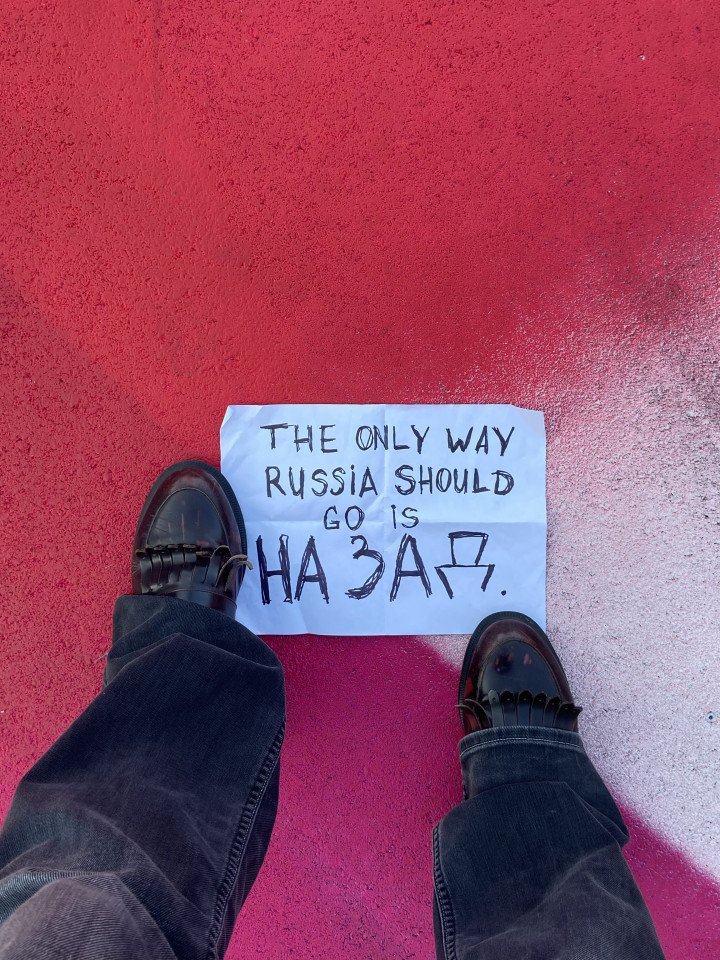

Having experienced Russian “movement forward” enough by now, I took a piece of paper, wrote “the only way Russia should go is ‘НАЗАД’ [back]” on it, and raised it above my head.

The Art Basel staff did not leave my suggestion unattended and came to speak. My response, according to Art Basel staff, was “too literal”—too personal, implying that my interpretation was governed mainly by my personal experience. And they were right.

However, they must have missed one thing: It is the knowledge gained from this exact experience. My concern about Bulatov’s works stems directly from it. From the context they tried to ignore.

So let’s be clear about the timeline and context. The Forward paintings were created in 2015–2016—two years after Russia first invaded Ukraine. At the same time, the slogan “ВПЕРЁД” ("Forward") was gaining renewed traction in Russian propaganda, including in Oleg Gazmanov’s 2015 song Вперёд, Россия [Go forward, Russia]—a patriotic anthem backed by fighter jets on its cover, promoting a vision of revived imperial strength.

In 2018, Bulatov collaborated with Russian designer Gosha Rubchinskiy on an autumn/winter collection presented in Yekaterinburg, Russia. The show featured Bulatov’s artwork, militarized streetwear, and not a hint of critique.

The same Rubchinskiy returned in 2025 with a new project titled День Победы ("Victory Day ") at Photo London—once again dipping into Soviet iconography without accountability.

Despite his reputation for producing work often interpreted as anti-authoritarian, Bulatov’s paintings continue to circulate among Russian elites, with reports—including from Russian media—suggesting that figures like Russian billionaire oligarch Roman Abramovich have purchased his pieces. His recent exhibitions include solo shows at the Nizhny Novgorod State Art Museum (2023), the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow (2024), and, of course, his prominent display at Art Basel (2025).

Bulatov offered no statement about the Russian invasion of Ukraine and hasn’t commented when an anonymous Ukrainian artist wrote the phrase “Russia is a terrorist state. Art is political” directly on the floor beneath the diptych on the Art Basel opening day (the phrase was successfully removed and unanswered).

In one of his interviews Bulatov has described Forward as stemming from his visit to an old foundry-turned-gallery in 2015. According to AMMA Studio , “he coined the word ‘forward' to encapsulate the aspirations of his generation and its subsequent state of disillusionment with reality.”

As much as I would want it to, the word “ВПЕРЁД” does not lose its charge just because a gallery calls it “form.” That’s like painting “Blut und Boden” in retro fonts and calling it design theory.

This is not just “unfortunate timing.” This is a curatorial decision that refuses to think politically, while bathing in political aesthetics. And here’s the paradox: tey get to borrow Soviet slogans and iconography—but deny any responsibility for what those symbols still do in the world.

Form obscures function

Contemporary theorists of subversive affirmation , like German curator Inke Arns and Slavist Sylvia Sasse, point out that strategies where creators incorporate dominant ideological aesthetics—such as Soviet slogans, uniforms, and iconography—only to reveal their symbolic nature rather than endorse them always involve a simultaneous distancing. The theorists caution that presenting such imagery without context risks neutralizing its critical power, effectively silencing what those symbols continue to signify in the present.

Although Russia’s aggression has continued into its fourth year, Western institutions remain willing to platform Russian cultural figures with clear pro-Kremlin ties. Soprano Anna Netrebko, who has long praised Putin and never condemned the war, is set to perform at the Zurich Opera House in November 2025, despite her 2024 concert cancellation over security concerns. Valery Gergiev, Russian conductor and another vocal Putin supporter, is scheduled to conduct in Spain in 2026, despite being dropped from several major orchestras in 2022. Sergei Polunin, the controversial ballet dancer with Putin tattoos and pro-Putin views, continues to tour internationally, with planned performances through 2025. Seems like Western galleries, opera houses, and festivals are once again open to artists aligned with a regime actively waging war—as long as the message is muted behind aesthetic distance.

The description on the wall near Bulatov’s work asks: “What does forward mean?

To understand that we might need a map. The directions may vary: perhaps Georgia (again?) or Baltic countries (where Soviets once marched equipped by “their powerful graphic skills”).

But the question from the curatorial text that interests me the most and that I'd like to reverse to Art Basel is Where are we going? And why?

I am still waiting for a response from the Art Basel Unlimited section curator, as promised, and I will be glad to engage in the dialogue to contextualise their choice of artworks.

-7a6104529316d12703ad12dcfd198ea4.jpg)

-657d7bbeba9a445585e9a1f4bccfb076.jpg)

-c48eebd28583d39a724921453048d33f.jpg)

-56360f669cb982418f455a4b71d34e4e.jpeg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)