- Category

- Perspectives

Professor Timothy Snyder on Why Ukraine’s Road to Victory Runs Through Russia’s Total Defeat

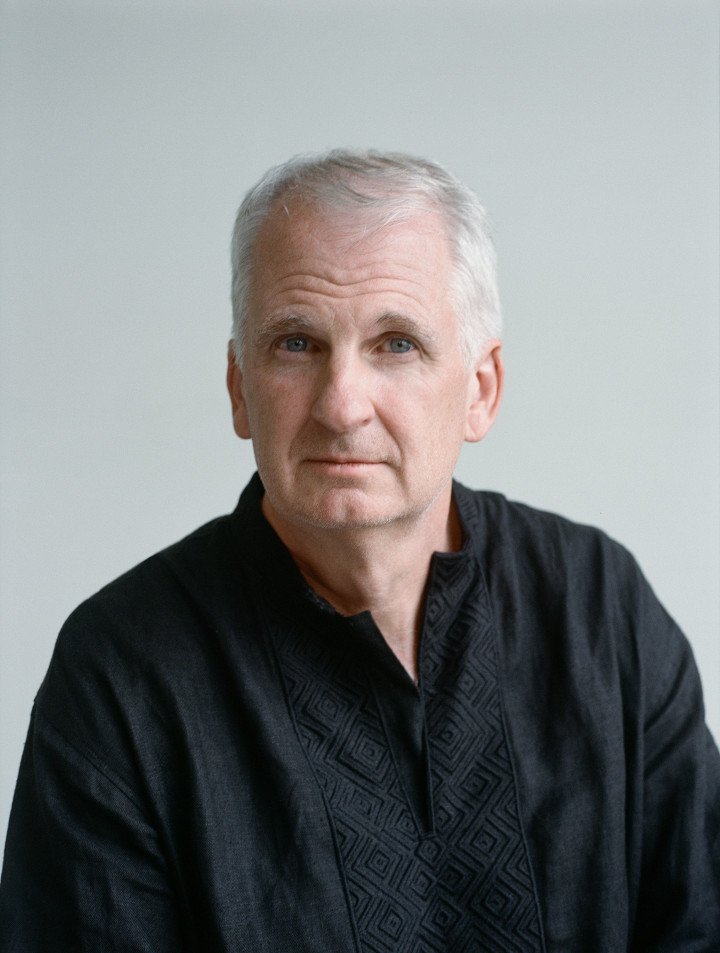

Renowned American historian Timothy Snyder shared his insights on the Ukrainian victory, the dangers of nuclear bluffing, and why Russia’s defeat is vital for the future of world security. In Kyiv, our reporter Zhenya Melnyk sat down with Professor Snyder to discuss some of the most pressing questions surrounding Ukraine today.

Professor Snyder is the author of several bestselling books, including Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, The Road to Unfreedom, and Our Malady. He holds the Richard C. Levin Professorship of History at Yale University and is a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. He also serves as an ambassador for UNITED24 and is a dedicated advocate for Ukraine.

When you were last in Ukraine, you said that the West must do everything possible to ensure that Ukraine wins—this will protect the next generation from the larger war. How do you think victory will look now, given the current situation?

A Ukrainian victory is when Ukrainians believe that they've won. But maybe more importantly, it's when Russians believe that they have lost. Russia has to lose in such a way that it doesn't start another war. I understand what Ukrainians think, first of all, in terms of their victory, but I tend to think in terms of Russia's defeat—[Russians] have to be defeated so that they know that they've been defeated. That, for me, is the key thing.

How exactly would that look like in your vision?

It's very hard to know what it looks like because the end of a war is a political thing. Nothing is purely military. Everything that is military is also political. In a dictatorial regime like Putin's, a war is over when the person who started the war doesn't want to do it anymore. Or when he's afraid the war is going to lead to him losing power or the war does, in fact, lead to him losing power. The way to think about winning is by applying various kinds of pressure to the center of the Russian state. Much of that is on the Ukrainian battlefield. But some of it is also economic and some of it's also psychological and some of it takes place inside Russia.

Now it is physically taking place inside Russia, I mean the Kursk operation. What is your opinion on that?

Americans don't always realize that we are very slow thinkers sometimes and we're very slow actors. As much as we've been on the right side in this war, and much as the people in the White House definitely want the right things and have done some very important things, we've tended to make up some new rules of warfare or even worse, we’ve accepted rules that the Russians made up and we somehow treat them as normal. So it's very important that Ukraine crossed the border, because when there's a war, when you've been invaded, you're allowed to strike back. International law permits that. Common sense pretty much demands it in a situation like this. It was an important lesson in reality, at least for a lot of Americans, because Ukraine crossed the Russian border and nothing happened.

The UK and the U.S. were supposed to allow Ukraine to finally strike inside Russia (during the Washington talks in September—ed.) That did not happen. A day before, Putin once again threatened escalation, stating that if Ukraine gets this permission to strike back, it's a war against NATO. Can we say that Russia is the number one threat to the world as we know it right now?

I read that whole thing quite differently. My understanding is that the only major victories the Russians are winning in this war are psychological. They're mostly psychological victories in American heads, in German heads. I don't connect anything that Putin says to any action that will then follow. What he's trying to do is to get us to do the things that he wants us to do. That's been his only success.

The whole business of nuclear war is there for us to be afraid so that we can act slowly. Our acting slowly is the only thing that has kept Russia in the war. So you can expect him to keep making these kinds of threats. That's totally normal. But he knows perfectly well two things. He knows that it's normal in a war, that if you attack a country, they might respond. He also knows perfectly well that if there was an intercontinental nuclear war—an exchange of ballistic missiles—he would be dead. He's not going to do that. And we knew that, too. There's no reason why we should be more afraid than he should be.

This war is a conventional war. It's been fought as a conventional war. If you let countries nuclear-bluff you, then you're giving them absolute power. If you say Russia can invade Ukraine because it has nuclear weapons and talks about them, that means Russia can invade Kazakhstan. It also means China can evade Taiwan. It means America can invade Mexico. It means anybody with a nuclear weapon is allowed to do whatever they want. That's a much less safe world than the one we're in now, not least because if nuclear bluffing works, then more countries are going to build nuclear weapons either to carry out nuclear bluffs or to defend themselves against nuclear bluffs.

You’ve visited Ukraine multiple times during the war. What did you notice that has changed in Ukrainian society, after nearly three years of full-scale war? The biggest war since the Second World War.

Most of what's changed is very sad. There are fewer people. More people have been killed or more people who have been injured. Another thing which has changed is the normality of it all. At first in 2022 one could believe that it would be over soon. One way or another, after the fall of 2022, one could imagine that Ukraine might win quickly. It's hard to imagine it ending quickly now, one way or another.

A third way, and I'll end with something a bit more positive, is that I think Ukrainians for the first time—not just in the last three years—but really coming to Ukraine for 30 years (I've been coming to Ukraine for a while, for a long time), it's the first time that I think Ukrainians are beginning to understand how good they are at things. I think one of the bits of Ukrainian national character is a kind of modesty, a sort of humility. Even when Ukrainians are very good at things, you don't really notice because they don't talk about it. But in my field, in culture, the last ten years have been extraordinary. Then the war years have also been extraordinary. The poetry and the prose of the war has been extraordinary. There are a lot of marvelous Ukrainian journalists and Ukrainian culture in general. I mean, Ukrainian textiles, all sorts of fields and culture have gone really well. And in fighting the war itself, right? Ukraine had certain kinds of help for sure, but an awful lot of things Ukrainians had to figure out for themselves. An awful lot of things Ukrainians had to make for themselves and an awful lot of things Ukrainians had to repair for themselves—and they've done all of that. I think now there's a bit more awareness that in this world, where there have always been Poles and Germans and Russians and so on, Ukrainians are actually capable of doing a lot of things. That's what I think Ukrainians now take for granted in a way that maybe they didn't three years ago.

Putin often uses history to justify the invasion, depicting Ukraine as a byproduct of a great Russian empire. He repeats the same justification time and time again, in the interview with Tucker Carlson also. How did Putin manage to convince not just Russia, and not just his inner circle, but even the West of his version of history?

That's a great question, and I'm going to answer it as a historian. History is very important. If we don't teach kids history seriously at university, then there's a big vacuum where there's just a big empty space and then any dictator can come along and fill that space. Putin does this quite well. Other people do it, too. We don't know anything about the past. Therefore when someone tells us a fairytale or someone tells us a story or a myth, we believe it.

This version of history which Putin is telling, his particular telling of it, is quite brutal and simplified and particularly idiotic. It comes from the Russian imperial historiography of the 19th century. This basic story about Vladimir and the Baptism, that basic story has been taught in universities across Europe and North America for almost 100 years. If anybody knows anything about Russia, they've probably read a textbook that has, again, a more subtle version of what Putin says. But the idea that something called “Russia” began a thousand years ago because someone called Vladimir got baptized and somehow nothing has changed since then, that basic story was an imperial story, which was spread well beyond Russia well before any of us were born.

We haven't taught history. History is important not just for knowing facts, right? It's important to know that the Rus were Scandinavians. It's important to know that the man that you'd like to call Volodymyr, had a very complex life. It's important to know that many things happened on these territories well before Rus, and many things happened on these territories well before Russia. It's important to know things, but it's also just important to know how to be critical. If you don't know history, you don't know how to be critical of someone else's story, you just kind of tolerate it. Then when you tell a story like this, you're tolerating the idea that the really existing people, who are on the planet, are doing things that somehow shouldn't exist because they don't fit the story, right? You can't tolerate that sort of thing. You have to be critical. But to be critical, you have to have practice in being critical.

Do you notice any tendencies in the way that Ukrainian history is being taught now, in Europe or the United States? Is anything changing?

It's changing fast. I mean, this is another thing that has changed. That has to do a little bit with modesty. Maidan helped a little bit, but the war has helped a lot, Ukraine has become a “normal” European country. It's misunderstood now on similar levels to other European countries. You've entered this kind of European community of misunderstanding where each European country knows a little bit about its neighbors. But I think that's reassuring. Ukraine belongs to this group now where no educated person would now say, “I don't have to know anything about Ukraine.There's no such place as Ukraine.” That has really changed.

But history teaching moves really slowly because somebody has to write a book. Somebody has to write a textbook. Somebody has to revise the textbooks. So it takes five or ten years for these things to actually cycle through.

I'm doing another big project called Ukrainian History Global Initiative, along with about 90 colleagues, most of them Ukrainians, for the next three years, which is about producing a big, accessible history of these lands and peoples. Hopefully, that will help with this problem.

Given the terrible similarities with how events developed in the Second World War, like the invasion of Poland by Germany, the same thing [is happening] now in Ukraine. How far are we, or are we close even to, World War Three, and what can be done to prevent this?

This is a conflict on the scale of a World War. The casualties are on the scale of a World War. The only real comparisons for wars this big in Europe are the First and Second World Wars. The terrain in question is also roughly the same. Ukraine was very important in the First World War and it was absolutely central to the Second World War. The curious thing is that it's a World War in which only one country is fighting. Those of us who are not fighting, I think, should see it that way. Rather than saying, “Ukraine has a war and that's a problem, we're worried,” we should say, “Ukraine is doing all this by itself. They're holding off something much worse,” which is the second way that I see this analogy.

If I were going to use an analogy, it would be Czechoslovakia in 1938. Ukraine is Czechoslovakia, and it’s an imperfect democracy in Eastern Europe. Ukraine has a complicated history, a complicated politics, but it’s a democracy and things are basically going in the right direction. And then it has a neighbor who says it doesn’t have a right to exist, “Your nation isn't really real. Your leaders are corrupt. I have the right to invade you.” That's what Germany says about Czechoslovakia in 1937 and 1938. That's what Putin says about Ukraine.

The difference is that Czechoslovakia didn't resist. If they had resisted, things might have been very different. Ukraine did resist. And since it resisted and it’s still fighting two and a half years in, that means that it’s keeping us in 1938—and 1938 is not a great time, but it's better than 1939 and is better than 1940 or 40, 41 or 42.

If we think about the analogy in terms of place, it's that it's a World War, but one country is fighting it. If you think about it in terms of time, I think Ukraine’s efforts are keeping us all in 1938. I think about this all the time—I think about how people in California, or in Ireland, or in Sicily or whatever, are just living their normal lives, like in 1938. Sure there's stuff that they're afraid of, and they might talk about it, but they just get to live their normal lives because Ukraine is keeping [the world] there. And so the idea would be to stop it. World War is won on these terrains because we understand what the stakes are.

Yesterday you were called the most efficient UNITED24 ambassador. How come it is so important to you, and how come you're so productive?

It's important for me because there's this horrible war and there are people out there in the world who really want to do something, but they don't know how, and they don't know who to trust and they don't know what channel to act through. So what UNITED24 does with its ambassadors is it says, “Hey! Look! Here are some people who you might like or you can trust. Here's Imagine Dragons. Here's Brad Paisley. Here's Mark Hamill. Here's Tim Snyder. They're going to show you something that you can do.” In that way, people can do something, feel like they're doing the right thing, and that the thing they’re doing is consequential.

The stuff that Mark Hamill does is consequential. It actually makes a difference. I like to think that our drone project and our demining project are consequential. It actually makes a difference. So UNITED24 is linking up this country with the rest of the world. It’s linking up people here with people elsewhere who want to help. It’s making a bit of a difference in the war or it’s making people safer during the war. That's why it's important to me. It's making the connection because when people give $5 or $50 to UNITED24, the money is important.

[Donors also] think, “Okay, like now I've done the right thing today and I'm doing it along with other people. I'm doing it along with this guy I admire, but also I know I'm doing it along with 100 other people or a thousand other people.” That little bit of solidarity. What is that? There are good people who want to do something, but they need to know they're doing it with other people and that it's serving some specific purpose, which [us ambassadors] can explain. You guys make that possible.

UNITED24 Ambassadors Timothy Snyder and Mark Hamill are raising funds for 30 demining robots to clear 139,300 square kilometers of explosive-contaminated land in Ukraine through the SAFE TERRAIN fundraiser. Donate now to help make Ukraine safe.

-588ae190d45987800620301cc34e2cf8.png)

-886b3bf9b784dd9e80ce2881d3289ad8.png)

-c42261175cd1ec4a358bec039722d44f.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)