- Category

- War in Ukraine

Not Kids Anymore. Six Stories of Ukrainian Gen Z Who Defend Their Country

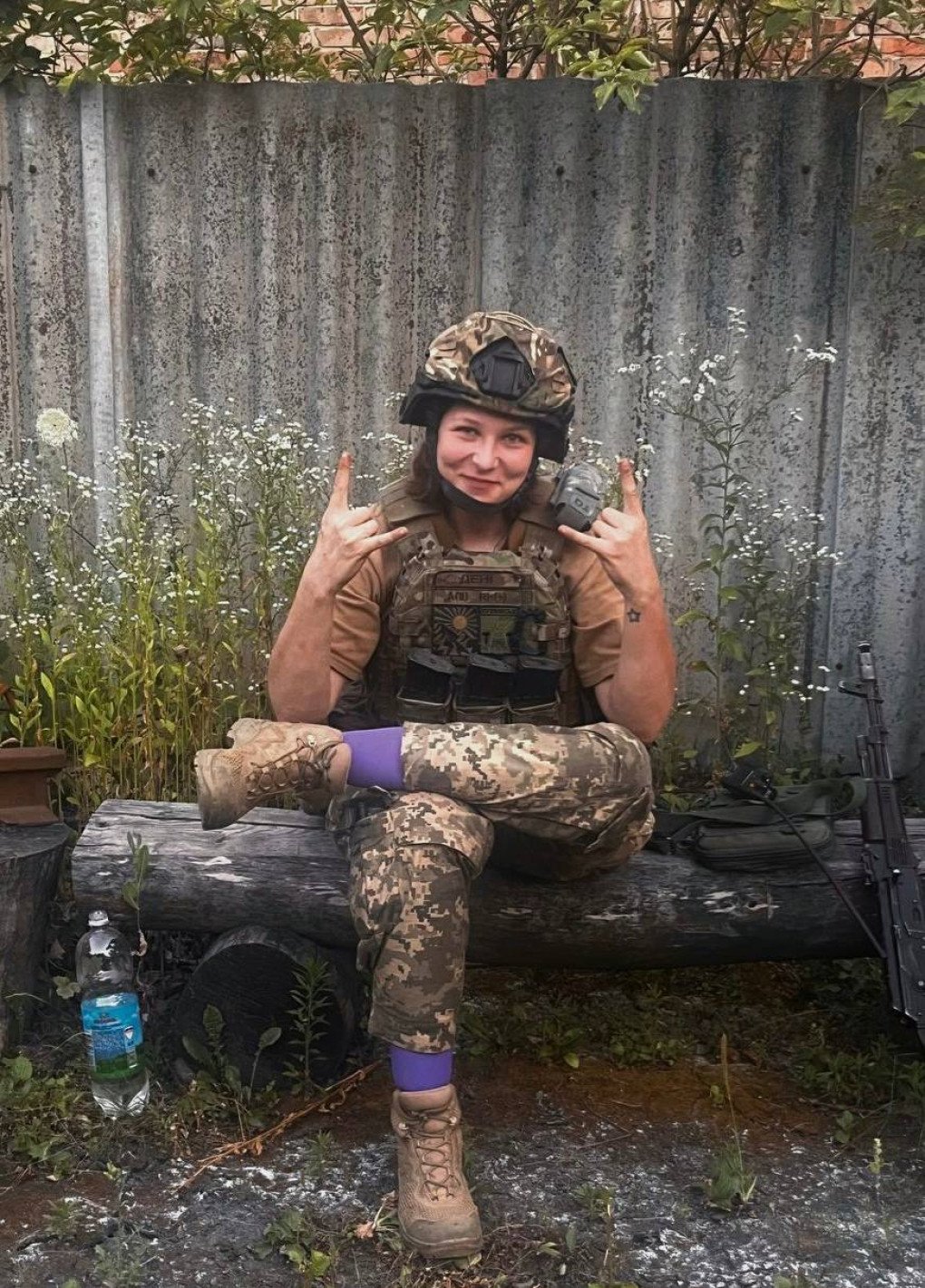

“I had a wonderful childhood, a great life, and good friends,” says Dany, a 27-year-old drone pilot, recalling her home city of Luhansk with a wistful smile. When Russia occupied Luhansk in 2014, she was just 16. Today, as Russia bombards Kharkiv and Kyiv—the cities she now calls home—Dany is no longer a child. Today, she serves in the Ukrainian Armed Forces and fights back. “I won’t let them take my home from me twice.”

Ukrainian Generation Z has been born to a free and independent Ukraine—the only Ukraine they’ve ever known and the only one they want to live in. When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, these young Ukrainians faced the stark reality that had loomed over their adolescence: Russia’s war.

Since 2015, Ukraine’s Ministry of Youth and Sports has tracked its youth perspectives. In a 2023 poll, over 80% rejected territorial concessions for peace, calling instead for Russia’s demilitarization, nuclear disarmament, and a buffer zone, while advocating for stronger Ukrainian military capabilities.

We spoke with six Ukrainian young adults who joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces in 2022 to defend their country: Dany, Ivan, Kyrylo, Maksym, Oleksandr, and Typhoon. They come from various corners of Ukraine and have unique journeys to this decision. Their motivations and experiences, however, share a common goal: to protect their homes and loved ones.

Growing up amid war

At just 16, Dany’s understanding of the war was still childlike. Yet, she grew up fast. Her fight first started when Russia’s grip tightened on Luhansk. “My friends and I would paint Ukrainian flags on walls, attend pro-Ukrainian rallies, and try, in our naive, childish way, to disrupt the Russian propaganda. We’d paint over Russian symbols with Ukrainian ones. Often, ‘militants’ would stop us, threatening to shoot us in the knees or take us to the basement. They’d find our blue and yellow paint and ask what it was for. We’d reply, ‘It’s blue and yellow; what do you think it’s for?’ They were so dumb.”

She remembers the danger vividly. “There were stories of people being taken or shot for speaking Ukrainian. I attended a pro-Ukrainian rally in Luhansk, where a shooting erupted. We were there for 10-15 minutes before chaos broke out. No one knew where the shots came from, and everyone scattered. Despite being naive children, we did everything we could to assert that Luhansk is Ukraine.”

Dany saw people at rallies with Russian flags, pretending to be Ukrainians who supported Russia’s presence. “You could tell they weren’t locals. Some locals supported it, but there were many outsiders. They’d ask in Russian, ‘How do I get there? Where is this? What is this?’ I’d think, if you’re a local, why don’t you know your own city?”

Oleksandr, a 23-year-old captain in the Ukrainian Armed Forces and Kyiv native, recalls, “I was in the ninth grade. Our school was close to Maidan , and we saw the echoes of the protests even during class. My uncle and father, both military servicemen, immediately went to Donbas to defend our land.”

Ivan, a 24-year-old combatant, was also just a schoolboy back then. He remembers sneaking out to see the protests. “I climbed on some of the barricades and saw with my own two eyes what was going on. Then I quickly ran home because my mom would kill me. I told her, ‘You know what is happening at Maidan?’ She said, ‘What? Have you been to Maidan? I told you to stay back!’”

Kyrylo, a 23-year-old Ukrainian Armed Forces officer, recalls more than just the Revolution of Dignity. “My earliest memories include the Orange Revolution in Dnipro, where I was sitting on my dad’s shoulders with orange ribbons. In a way, I belong to the generation molded by Ukrainian revolutions.”

Kyrylo’s teenage years were a whirlwind of change. In 2013, he witnessed the emergence of a nation with a heightened sense of civic duty. By spring 2014, the atmosphere was charged with fear, though he says Dnipro felt less intense compared to Kharkiv, Odesa, or Donbas. “The annexation of Crimea marked the end of my childhood.”

Kyrylo talks about the early days of the ATO with a heavy heart. “Dnipro became a key coordination center for eastern Ukraine. We saw the first major losses in late spring and early summer, especially after the Il-76 aircraft was shot down near Luhansk, carrying soldiers from brigades in Dnipro and its outskirts. The image of Lenin’s monument being toppled in Dnipro’s central square, juxtaposed with old Soviet cars unloading coffins, set to the haunting melody of ‘A Duckling Swims in the Tysa,’ became a stark symbol of our fallen soldiers.”

Maksym, a 23-year-old senior soldier in the Ukrainian army, also recalls this folk song. “Watching those farewells on TV was heart-wrenching. Each tribute, each ‘Duckling Swims in the Tysa,’ was a painful reminder.”

Maksym hails from Mytchenky near Baturyn, the historic “Hetman’s capital” in the Chernihiv region. He shares his story with a chuckle. “Growing up, I was quite a rascal.” Maksym’s sports school coach, however, shaped his worldview, instilling a deep appreciation for his land and its history. “The Revolution of Dignity was a powerful and rare event in our country, but to me, it was also a form of expression. Then, the students were beaten, and many people joined the movement. The fear of uncertainty, especially with Yanukovych in power and the possibility of falling under Russian control, was terrifying.”

Growing up, Maksym did what he knew best—helping people. “I got involved in volunteer work in Chernihiv and Kharkiv, organizing lectures and media literacy projects. It was about making a difference.”

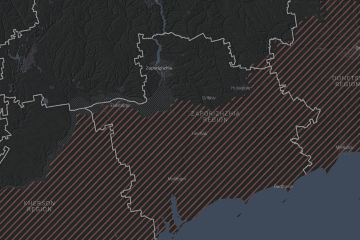

Typhoon, a 20-year-old mortar commander from Lutsk, looks back on his volunteer work in Svitlodarsk, a city in the Bakhmut district in the Donetsk region, with a hint of nostalgia.

“In 2021, I went there for an educational mission,” he says. “It was Christmas, and we organized nativity plays for the kids, while I gave talks about dissidents. I am a descendant of people from Chełm Land . It was interesting to talk to people from Donetsk, who, logically, don’t know much about Chełm Land.”

By 2022, Svitlodarsk and then Bakhmut fell under Russian occupation. When Russia’s assault was devastating Bakhmut, Typhoon was on the front lines, fighting for the ones he had come to understand and cherish. “My goal was to stand up for those lands,” he says. “I had seen that region and its youth. I know many people who have lost their homes.”

Facing Russian invasion again: February 24, 2022

“As my comrade put it, ‘By February 24th, everyone had chosen the path their life had prepared them for,’” said Typhoon. His grandmother’s cries woke him up. She handed him the phone, and his father’s voice came through, “Son, get up, the war has started.” With no prior combat experience, he immediately sought out volunteer battalions and was placed in the reserve section of one.

Ivan was abroad studying video game development when he received a call from his mother, saying, “Son, I think the war broke out.” Ivan has never heard bombardments before, “But that's when I heard it: on the phone, talking with my mother,” he says.

He packed a small backpack and rushed home to Kyiv, arriving just as Russian troops were closing in. The bus driver nearly led them into a Russian ambush.

“Our guys saved us,” Ivan recounts with a hint of humor. “We ran into a Ukrainian tank, and in my autistic head, I thought, ‘Oh, this is like in Fury with Brad Pitt!’”

But then reality hit—Ivan was in real danger. “The tank commander asked, ‘What are you doing? Where are you going?’ to which we replied, ‘We’re going home!’ Frustrated, the commander said ‘Don’t you know, Russians are over there?”

Ivan joined Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Battalion as soon as he arrived. “Did we stoically defend Kyiv?” he smiles. “No, we were just defending some of the first Javelins when they came to Kyiv.”

When a group was being assembled to break the Azovstal encirclement, Ivan eagerly volunteered. “It was a one-way trip. I thought, ‘Alright, let’s fight like hell.” But fate had other plans—the unit had to be trained first. “This is where the real movie starts,” he says. “Imagine any movie where they are preparing Navy Seals. They gave us these three weeks of hell.”

Typhoon’s training, led by Americans, Finns, and Lithuanians, was equally grueling. “They taught us how to communicate. Essential in combat.”

Only after rigorous training did Typhoon and Ivan finally see a real battle. “When I got back from the first battlefield, I understood that that's a lot more than I was asking for,” says Ivan. “But I wasn't complaining at all.”

“We had this image of war from World War II, trenches, and everyone dying,” says Dany. “I mentally said goodbye to everyone and went into the unknown. In reality, I started intercepting Russian communications and gradually moved closer to the front lines, eventually flying drones within a kilometer of the enemy.”

Oleksandr was the only one of the six with full military training before the full-scale invasion, thanks to his military academy education. His training proved crucial when the invasion began. Despite this, he faced challenges adjusting to working with much older colleagues. “Some were old enough to be my grandfathers! But we formed a strong team.”

Kyrylo, witnessing Kyiv’s transformation into a ghost town on February 24, saw long lines for essentials and the looming threat of Russian troops entering the city. “The thought of seeing Russian flags or tanks at places like St. Sophia Cathedral was unimaginable. We were conscripted, first as soldiers and then as junior sergeants, rather than officers. We put on the uniforms we had from our military training department and went to enlist.”

Kyrylo’s commitment to his country led him to represent Ukrainian youth at the UN, participating in the 78th UN General Assembly as a delegate and engaging in international events.

What fuels the resolve of Ukrainian youth

“I want to reclaim my home in Luhansk,” Dany declares with steely determination. “I didn’t like the frozen conflict in Donbas, the Minsk Agreements that left us vulnerable. Watching our forces get shot at, unable to respond was excruciating, especially with so little international action.”

Dany says she is ready to fight for the full restoration of Ukrainian territory to the 1991 borders and to join NATO and the EU. She dreams of rebuilding Donbas and other cities, devastated by Russia. “It might be idealistic, but it’s my ultimate goal. We must see this through to the end.”

For Oleksandr, the motivation is straightforward. “This is my country, where I grew up. This is where my family lives, and where my future children will grow up. I refuse to let the enemy occupy my land. This conviction drives me forward.”

Maksym’s drive is deeply personal. “My main goal is to save as many of our people as possible. It’s also about my younger brother, who is just 11 years old. He once opened up to me and told me his dream is for the war to end. That really struck me. Usually, he’d say, ‘I want a toy car,’ which is understandable because he is still young. I know why he said this, though—he looks up to me, he misses me. I want to make sure he grows up in peace.”

Ivan’s motivation is rooted in love and duty. “Everything I hold dear being right here keeps me going. This is my country, my land. My mother, who was always furious with me, and my granddad who’s about 98 years old. God bless him. My countless brothers and sisters in arms—they all need protection.”

He smiles and asks if I know who Billy Talent is. “There’s a song that goes, ‘When the storm hits your front door…’ What will you do? Will you turn your back or will you run away? You can’t run forever. Everyone will face their storm eventually.”

Ukrainian young generation’s vision for the future

“I don’t think much about the future—maybe just the short-term future,” Typhoon admits. He compares his mindset to U.S. Admiral William McRaven’s advice during SEAL selection: “When you’re facing hell week, every five minutes your body wants to quit. The trick is—not to think globally.”

Thinking too much about everything happening at the front and behind the lines can be overwhelming. Typhoon focuses on staying cool-headed and rational, breaking his tasks into small, manageable steps. “That’s how I’ve adapted to this life.”

“Before the war, I thought about 50 years ahead,” says Maksym, “Now, it’s more like one or two years.”

He hopes Ukraine—and its people—will embrace change more readily. “We need to stop resisting necessary transformations. Change is hard, but it’s needed from government officials to everyday citizens.”

Ivan envisions his future as an instructor. “We’ll need to train our civilians to handle stressful environments. With constant threats of bombardments and shellings, people need to know how to defend themselves and operate firearms. The days of computer games are behind me.”

Ivan later adds that his future depends on two things: if the war ends and if he is still alive.

“Our generation has to work tirelessly, regardless of whether the outcome is optimistic,” Kyrylo says, his expression serious, heavy. “We must move beyond old notions of a happy life. The country we were born into has a unique global role: to demonstrate that the ideas and values of past decades—centered on self-satisfaction and healthy selfishness—are no longer feasible. Whether for better or worse, this is our new reality. We must work hard, even if the world hasn’t caught up. Our role is to be an example, even if it’s an unpleasant one.”

Ukrainian Gen z’s message to the world

“The youth defending Ukraine are both courageous and diverse,” Maksym says, adding that he doesn’t want people to romanticize them. “Their motivations vary widely. Some are driven by boldness and desperation, while others are guided by thoughtfulness and strategy.”

Many of his comrades, aged 18 to 25, are still grappling with the scars of war. “Young people are struggling to forge a stable identity under constant strain. We need more understanding and patience. All servicemen and women deserve support—not just in resources but in personal connections.”

Thinking of his brother, Maksym urges to nurture the future generation. “Those in their early twenties today are bearing the toll of this war. [The even younger generation] will need to honor those who fought for them—both the living and the fallen.”

Typhoon underscores that his generation is not one that was drafted or coerced. “I could have avoided military service by staying in university until I was 25. Instead, I’m in my third year of combat. We’re a unique generation because we chose to fight.”

He implores to approach his generation’s decisions with understanding. “We’ve risked our young, unformed lives with no place to return to once all this chaos ends.”

Ivan reflects on his experience, advising, “Prepare yourself, mentally and physically. Not just for your possible conscription, ending up in a war. Every day you are going to experience something traumatic or something that will shape your very core of existence, you gotta be ready for it.”

His message is existential, reminding that any moment can be the last one, especially for those who live in Ukraine. “If you live in the outside world—pay attention to Ukraine. Don’t think it will just blow over. What is happening here is going to have ramifications of untold magnitude. Whether it’s oil prices or the probability of the Third World War, you got to be ready. And don’t forget—appreciate what you have at this moment.”

Dany’s message is one of hope and action: “It’s tough, and I struggle with hope too. But believe and do what you can. Donate if you can, or join the Armed Forces. Collective action makes a difference. We need unity and kindness.”

She reminds that the young people defending Ukraine embody the country’s pride and hope. “Many young defenders are just in their twenties, serving as assault troops and pilots. My closest friend joined at 18 and is now 20. It’s an honor to witness this new, conscientious generation emerge, carrying forward the legacy of those who have fallen.”

She pauses, then smiles, “I am deeply proud to serve alongside them in the Armed Forces of Ukraine.”

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)