- Category

- War in Ukraine

One Night with a Drone Hunting Unit, Guarding Ukraine’s Skies

Every day across Ukraine, sirens pierce the skies. Someone, somewhere, is in danger—or worse. But who are the men and women working behind the scenes to protect them? When the sirens sound, they don’t run to bomb shelters. Instead, they rush to their posts, ready to defend.

Go time

It’s 8:30 p.m. and the sun has set in southern Ukraine. Our team stops at a gas station—it’s the last place of safety before we head off into the night to hunt for drones with Ukraine’s 35th Marine Brigade. My colleagues and I strap up in the parking lot with body armor and helmets, and it’s hard to tell if the weight on my chest is from the metal plates or the anticipation of potentially being gunned down by a Russian Shahed drone.

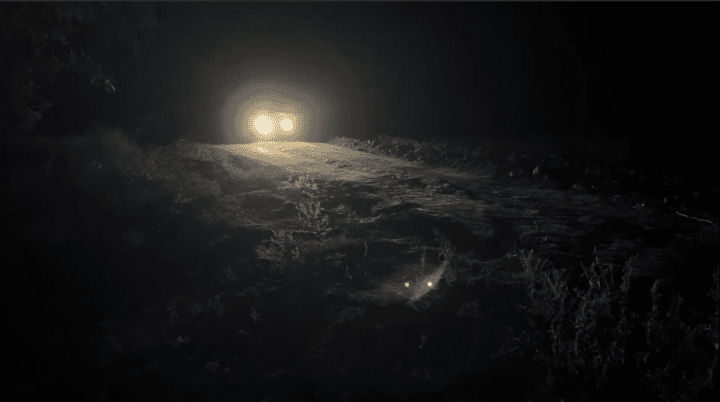

We drive in silence towards the Google pin, which leads to an undetermined location off the side of the highway. As we pull off the road, the only landmark in sight is a bombed-out petrol station—no doubt destroyed in the crossfire of the counteroffensive of November 2022, when Ukrainian Armed Forces pushed Russia out of Kherson city. Our headlights illuminate a car with two men standing outside it—members of the brigade are waiting to meet us. After verifying our IDs, we get in their vehicle and take off into the night with great speed and little regard for the axle.

Along the journey, we make small talk with the soldiers. My two colleagues and I sit shoulder to shoulder in the back seat while the press officer and another soldier sit in the front. The car travels further and further into Ukraine’s sprawling sunflower fields. I sigh and try to let go of any last bit of expectation or control I think I have over this evening.

The car suddenly slows down as a flashlight blinks twice in the distance. With a sharp jerk, we veer off toward the light. The man holding the flashlight is the head of the unit. We step out of the vehicle and follow him into the field, guided by the red glow of his torch.

“You are journalists?” he asks as we trudge through the dirt. He tells me how important it is for the West to see what Ukrainian soldiers are doing here, how hard they are working to protect their freedom. This war, perhaps more than any other, relies heavily on fundraising, forcing brigades to get creative by using social media and the press to equip themselves. Out here in the tall grasses of Ukraine’s farm fields, the champagne politics of Washington feel like a world away. Listening to the commanders' words, I’m reminded of the John Donne poem “For Whom the Bell Tolls.”

No man is an island, Entire of itself. Each is a piece of the continent, A part of the main. If a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe is the less. As well as if a promontory were. As well as if a manor of thine own Or of thine friend’s were. Each man’s death diminishes me, For I am involved in mankind. Therefore, send not to know For whom the bell tolls, It tolls for thee. |

I walk clumsily, struggling to keep up in the dark, when suddenly we come upon it—the drone hunter. Slightly larger than a pickup truck, it sits inconspicuously among the tall grasses. Beneath a camo net, a mounted machine gun rests on its tail bed. This vehicle, like many others, is part of a vast network of thousands of drone hunters.

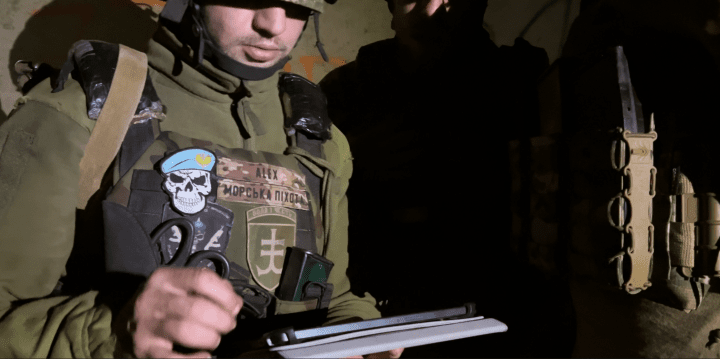

Each drone hunter communicates via a Command and Control system operated on a simple $150 Android Tablet. While not always accurate, the speed and cost of these tricked-out trucks outweigh the alternative. For shooting down drones, air defense missiles are simply not worth the cost, considering an interceptor missile for a Patriot system costs approximately four million US dollars.

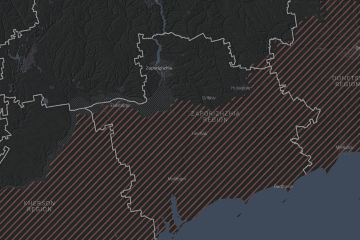

Though the soldiers can’t share exactly how far away the next unit is or how many there are, they tell me that a machine gun’s range is approximately 2.5 km. “We cover all of Ukraine’s territory,” says the commander. With the help of their software, these units create a grid across Ukraine of drone hunters ready to shoot down incoming threats.

Incoming threats

Our location is approximately 25 kilometers away from the frontline, which is too far for the FPV drones that have been terrorizing Kherson City by dropping petal mines and anti-personnel mines on civilians. This is a tactic chillingly referred to on Russian Telegram Channels as a “Human Safari”. Tonight, the primary threats are Iranian-supplied Shahed drones and surveillance drones.

There are, on occasion, larger incoming threats. The young men recount a story from ten days prior when Russia launched three large rockets: one weighing 500 kg and two 250 kg. One of the rockets landed dangerously close to their unit as they were resting, narrowly avoiding what could have been a devastating loss. Resting, it seems, is a significant part of their routine, and I’m reminded of Hemingway’s words: “Ask the infantry and ask the dead. They will tell you it’s about the waiting — ninety percent of war is waiting.”

They go on to explain that Shahed drones are typically launched between 9:00 p.m. and midnight, adhering to a surprisingly consistent schedule. Over time, Russian drones have been almost exclusively deployed under the cover of darkness, making them harder to detect and shoot down. Yet, there’s a darker dimension to this tactic: psychological warfare. By targeting Ukrainian cities at night, civilians are left lying awake, constantly on edge, their sense of safety eroded by the ever-present threat of an attack.

War is hell

After a short inspection of the vehicle, the soldiers beckon us into an abandoned grain storage a hundred yards away — too much light could betray our position to enemy surveillance drones. As I talk with the three young men and their captain, I can’t help but consider who they were before the war — an electrician living in Poland, one tells me, the other an artist. After the war, the electrician says he wants to stay in Ukraine and buy his own farm to grow strawberries. I don’t have the chance to talk to the third, who is tall, quiet, and conventionally attractive.

“War is hell,” one of them says. Looking at these bright-faced young men, it’s hard not to agree. After all, there isn’t much that separates us except the countries we were born in. We are all close in age, and it feels strange to speak with such formality—them as soldiers and me as a journalist.

Suddenly, the soldier holding the tablet is distracted. The three begin to chatter and move towards outside.

“Drone,” one of them turns and says. My fingers fumble to my camera as we quickly make our way toward the truck. The three soldiers are already on the tailgate. In the darkness, I hear the clanking of metal, the satisfying click of loaded ammunition, and then the eerie metallic creaking of the gun turning on its mount. Then silence.

“Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat” the gunman fires what sounds like hundreds of bullets into the sky. “Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat.” The other soldier is looking at his tablet. A spotlight ascends towards the sky, shining on a flying object. “Rat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat-tat.” A burst of orange light.

Click, clank, and then again, the metallic creaking of the gun swiveling back into a locked position. The other two soldiers climb back onto the tailgate and begin fastening the various bits before throwing the camo netting back over the machine gun. They pack up with a sense of urgency- it’s all too likely that a Russian recon drone has picked us up and the firing of incoming could be imminent.

“We go now,” one turns to me and says. The press officer beckons me back across the field, “Go, go, go,” and the three soldiers jump into the truck and drive away. I watch their red tail lights speed off ahead, my heart still racing. What had just happened? Did they shoot it down? Where were they going?

Silent guardians

Drone hunting units report an impressive 80% success rate. According to one of the developers of Kropyva Command and Control software, the margin for error depends solely on the gunner’s skills. Software systems like Kropyva provide exact coordinates to the drone hunting units, taking into account wind and other ballistic factors.

The destruction of a drone, however, is sometimes a group effort. One gun may “injure” a drone before the next one takes it down. No matter which unit is responsible, all the soldiers agree there’s no better feeling than shooting one out of the skies.

Making my way back toward Mykolayiv, the adrenaline begins to wear off, and I’m greeted by the familiar sight of the gas station whizzing by. The time is nearing curfew. Our vehicle is stopped at a checkpoint entering the city. “You’re going to your hotel?” the soldier asks. We nod, and he waves us through.

Back in Mykolayiv, the city is quiet. A few dim streetlights illuminate the empty sidewalks, and straggling cars whizz by to make it home before midnight. I think about the people sleeping peacefully before my mind wanders back to the three young soldiers. Somewhere in the darkness, they, and countless others like them, lie awake, gazing at the night sky—not for stars, but drones. When the air raid siren blares, they will spring into action while others take shelter in their homes. The siren, like a funeral bell, echoes its grim message: “Send not to know for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee.”

-fca37bf6b0e73483220d55f0816978cf.jpeg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)