- Category

- War in Ukraine

The Western Tech Inside Russia’s Warplanes Bombing Civilians

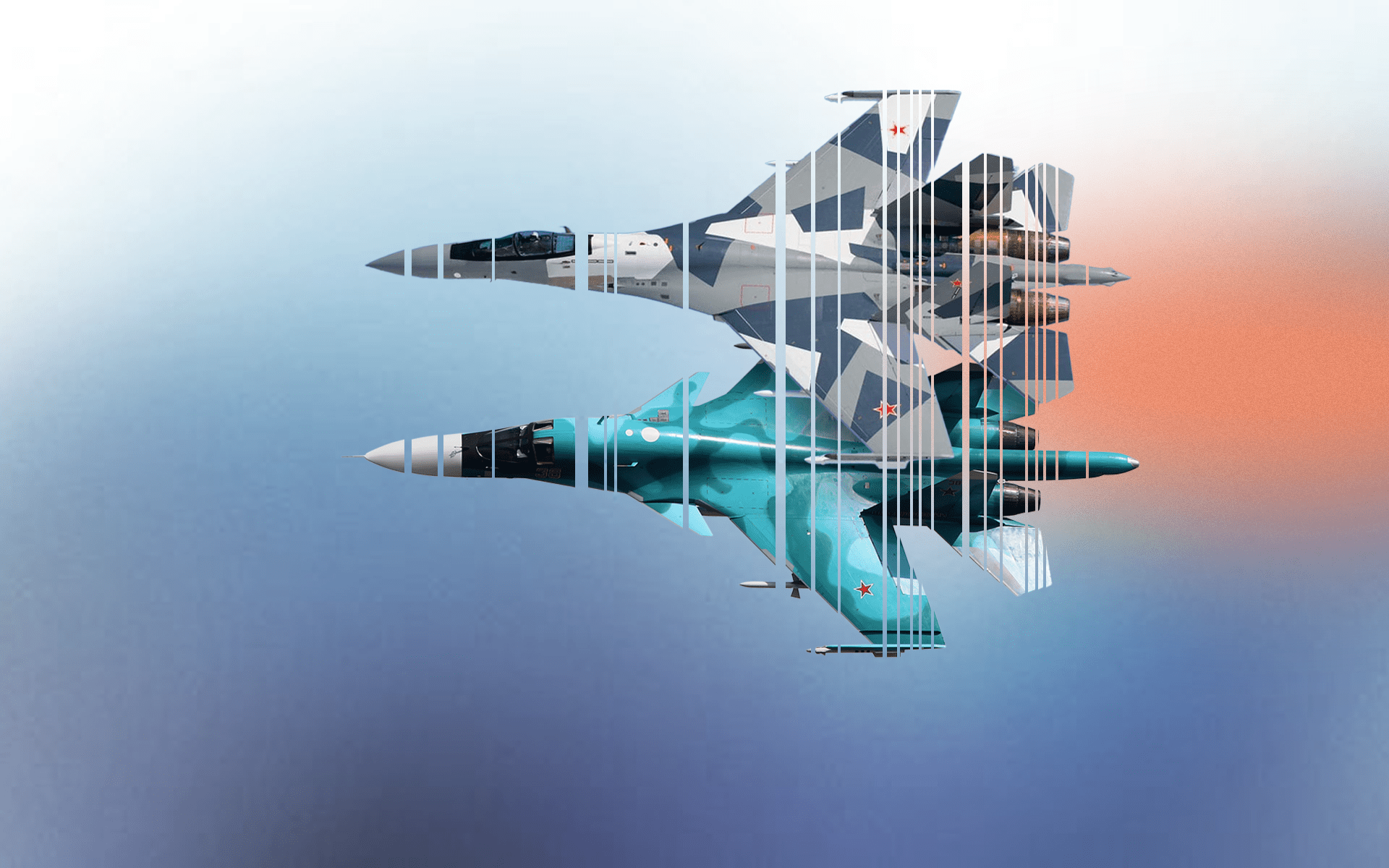

Despite more than a decade of sanctions, Western tech is still powering Russia’s deadliest weapons linked to deliberate strikes on Ukrainian civilians. A new investigation uncovered more than 1,100 foreign-made microchips inside Russia’s most advanced fighter jets: the Su-34 and Su-35.

The Su-34 and Su-35 are two of Russia’s most advanced combat aircraft, capable of hitting long-range targets while carrying a heavy payload of precision-guided munitions. These include KAB and UMPB D30-SN bombs, as well as Grom-1 missiles—the exact weapons that Russia has repeatedly used in strikes on civilian infrastructure across frontline cities in Ukraine.

These jets have been central to Russia’s role in at least 60 Russian airstrikes against Ukrainian cities between 2022 and 2024. These attacks killed 26 civilians and injured 109 more in places like Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Kherson, and Sumy. In all of them, no military targets were visible.

The new joint investigation by the International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR), NAKO, and Hunterbrook Media found instead the patterns of Russia’s deliberate strikes on civilian infrastructure—evidence that points directly to war crimes.

“Our findings are unambiguous: Russian aircraft committing probable war crimes are assembled with Western microchips,” said Ukraine’s Independent Anti-Corruption Commission (NAKO) Executive Director Olena Tregub.

What’s inside the Su-34 and Su-35

Ukrainian military and government investigators began by analyzing wreckage from downed Su-34 and Su-35S jets, alongside procurement data leaked from inside Russia. They combined this with high-resolution imagery of internal systems posted online. Together, these sources allowed for one of the most detailed open-source breakdowns of Russian jet avionics available outside of the Pentagon.

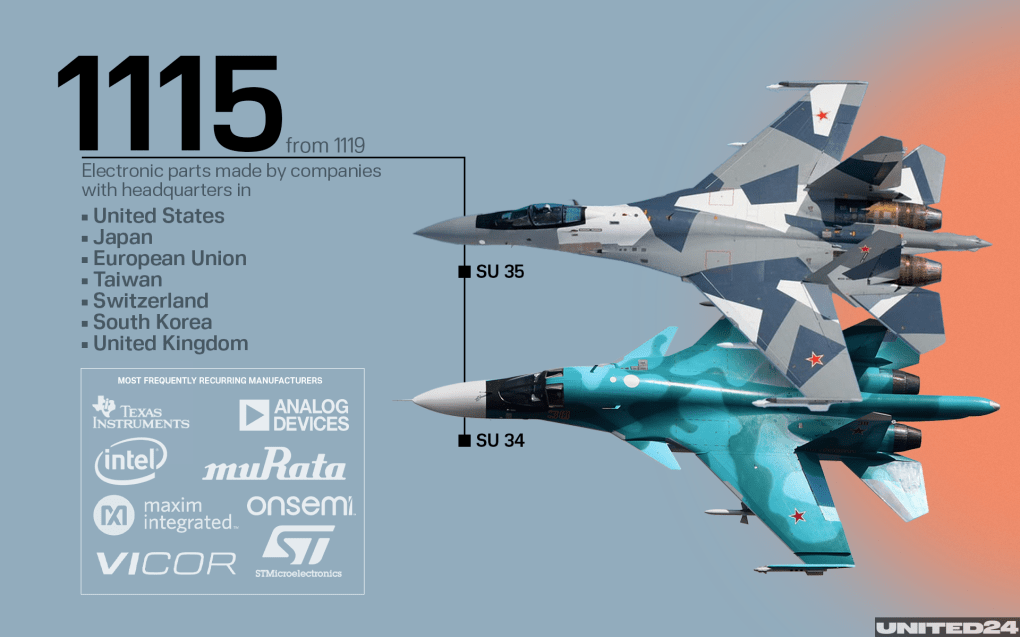

Out of 1,119 distinct components identified inside the Su-34 and Su-35, an almost unbelievable 1,115 were made by companies headquartered in the United States, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, or France. These aren't obscure parts or numbers; they are essentially every part of the plane that flies, navigates, and kills.

Some of the most frequently recurring manufacturers include:

Texas Instruments (US): Known for robust analog chips and microcontrollers that appear in radar interfaces and targeting computers.

Analog Devices (US): Supplies high-performance amplifiers and converters, used in signal processing and communication systems.

Intel (US): Their processors and memory chips have been found in mission computers and onboard data storage units.

Murata (Japan): Produces ceramic capacitors and filters, likely embedded in power management and navigation modules.

Maxim Integrated (US): Known for voltage regulators and signal chips that help manage everything from display outputs to missile control systems.

OnSemi (US): Supplies power transistors and diodes used in flight control electronics and thermal management.

Vicor (US): High-efficiency power converters that ensure the jet’s electronics remain operational under intense conditions.

STMicroelectronics (France): Found across a variety of systems, including GPS modules, inertial sensors, and microcontrollers for guidance and telemetry.

Each of these chips serves a critical function, from radar and guidance systems to flight control and communications. They allow these jets to lock onto targets, carry out precision strikes, and coordinate missions. The technology enabling those attacks (often on civilian infrastructure) is overwhelmingly Western.

These components are what make the Su-34 and Su-35 lethal: they handle navigation, targeting, radar, and electronic warfare. Without them, the fighter jets lose their edge. And most of this tech isn’t classified or hard to get; it’s commercial off-the-shelf, dual-use, and easily rerouted to Russia through third countries.

How Russia bypasses export restrictions

Sanctions were meant to cut Russia off. Since 2014—and even more aggressively after the 2022 full-scale invasion—Western governments have imposed export controls, blacklists, and licensing restrictions to restrict access to dual-use technology. But as the report notes, “the real problem lies in weak or absent end-user checks… Companies rarely follow up once their product leaves the warehouse.”

Russia’s microelectronics industry lags decades behind, still producing older‑generation chips that can’t match the performance needed for modern fighter jet avionics. Of the 1,119 components identified in the Su‑34 and Su‑35, 1,115 were made abroad, pointing towards a very apparent reliance on Western tech. Without the “gray” import networks keeping those parts flowing, much of Russia’s precision strike capability would eventually grind to a halt.

The report alleges that in 2023 alone, Russia imported more than $800 million worth of high-priority microelectronics, components essential for building missiles, drones, and combat aircraft such as the Su-34 and Su-35. These parts aren’t slipping through by accident. They’re being routed through a sprawling network of intermediaries, shell companies, and third-country distributors designed to exploit weak enforcement and jurisdictional gaps.

These “gray” supply chains operate out of:

China

Hong Kong

Türkiye

United Arab Emirates

Multiple EU member states

The process is simple: Companies in these countries legally buy dual-use electronics from Western manufacturers. They then re-export them to Russian firms tied to the defense sector, often under vague or incomplete end-use declarations. The paperwork may be clean, but the destination is clear.

As the report notes, “Russia’s procurement networks are adept at exploiting gaps in export controls and the complexity of global supply chains.” With no effective global system to track the end use of exported components, they can still move parts into Russia within weeks of placing an order.

The role of the US, Germany, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and France

It's been established that the electronics inside Russia’s most advanced fighter jets aren’t homegrown, but what’s concerning is that they come from companies headquartered in the United States, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and France.

Together, these companies manufacture nearly all the critical avionics-grade chips found in Russian Su-34 and Su-35 jets. We're talking about components for radar systems, satellite navigation, encrypted communications, flight control, and precision targeting. Some of the parts are niche and highly specialized. Others are off-the-shelf commercial goods that weren’t designed for weapons but ended up in them anyway.

Most of these firms have no direct ties to Russia’s defense industry. They aren’t shipping components to Moscow knowingly or breaking export laws outright. But their products keep ending up in Russian missiles and aircraft, because the global supply chain is massive, opaque, and designed for speed, not scrutiny.

A chip’s path from a Western factory to a Russian warplane is rarely a straight line. Investigators say a component manufactured in the Bay Area or Bavaria might be sold to an overseas distributor, packed into a bulk shipment with thousands of other commercial parts, and routed through logistics hubs in Dubai, Shenzhen, or Istanbul. From there, it can be re-exported under vague end-use declarations to a Russian importer posing as a civilian business. Within weeks, that chip could be installed in the radar or targeting systems of a Su-34 or Su-35 flying missions over Ukraine.

Each step looks legal in isolation, but taken together, it’s a sanctions evasion machine built on global trade, deregulated re-export markets, and the anonymizing qualities of sheer mass. That’s what makes it so effective. As the report notes, “Russia’s procurement networks are adept at exploiting gaps in export controls and the complexity of global supply chains.”

Strikes powered by imported tech

The report links Western-made microelectronics directly to Russian airstrikes on civilians in Ukraine. Investigators examined more than 60 attacks by Su‑34 and Su‑35 jets between 2022 and 2024, focusing on ten in Kharkiv, Kherson, Sumy, and Chernihiv regions. In those cases, Russian forces killed 26 civilians and wounded 109, using precision-guided KAB bombs and Grom‑1 missiles—munitions that depend on imported chips for guidance, navigation, and targeting.

One example came in March 2023 in the Kharkiv region, where a Su-34 dropped a KAB-500 guided bomb on a residential block, killing four people and injuring more than a dozen. Investigators found no military positions nearby. Another strike, in July 2023 in Chernihiv, hit a hospital complex, killing two staff members and wounding patients. Both attacks, the report says, were likely war crimes.

In each case, the jets’ avionics were powered by chips from companies in the US, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and France, which enabled the precision that made these strikes possible. The link is not speculative: the same component types identified in wreckage from downed aircraft match those required to operate the weapons used in these attacks.

Why it matters

This isn’t just a story about how Russia builds its weapons. It’s a spotlight on how the lack of market controls by the rest of the world lets them. The systems meant to control where sensitive tech ends up—licensing, verification, oversight—are undeniably flawed. The cost of its failures is measured in civilian deaths, cratered homes, and schools reduced to rubble.

If there’s a frontline in this war outside Ukraine, granted one that is not very dynamic, it runs through shipping routes, customs offices, and boardrooms in democratic countries. That’s where the next strike can be stopped—if anyone’s willing to take responsibility before the next shipment goes out.

The report doesn’t accuse manufacturers of breaking the law, but it shows how weak end-user controls, re-export loopholes, and an unmonitored global supply chain make sanctions easy to dodge. A chip made in California can end up in a Kharkiv airstrike with no one stopping it.

“Companies from democratic countries have a moral obligation to strengthen control over their supply chains,” said NAKO’s Olena Tregub. Governments and customs agencies share that responsibility, yet components keep appearing in Russian weapons. Firms typically insist they comply with all export laws, and officials point to expanded control lists — but evidence shows those measures aren’t enough.

The investigation identifies companies and governments whose components were found in Russian military aircraft, but makes no allegation of legal wrongdoing by the manufacturers. It does not claim that these companies directly or indirectly supplied the Russian military, breached sanctions, or violated any laws. Links between the components and Russian airstrikes in Ukraine are drawn solely to highlight ethical and moral concerns.

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)