- Category

- War in Ukraine

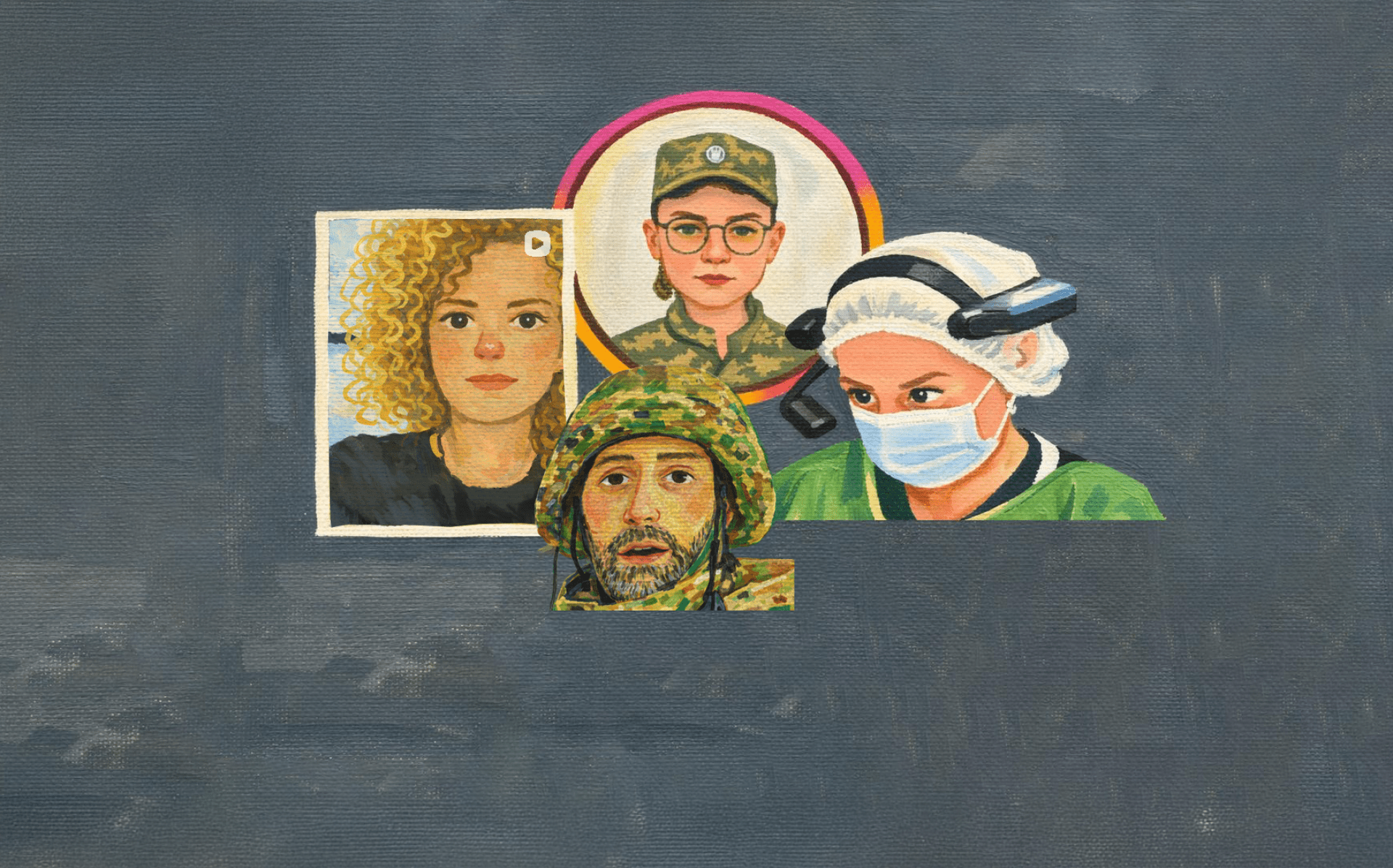

Why Resist? How Ukrainians United to Defend Their Freedom

“When your loved ones, your homeland, your entire nation are under threat—what do you do? You fight back.” For millions of Ukrainians, that answer has become a daily reality since Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has lasted nearly twelve years—this February 24 will mark four of it full-scale. Millions have taken part, each in their own way: soldiers, medics, volunteers. What keeps them going?

The healer at the front

Svitlana Halych, 61, is a professor and senior obstetrician-gynecologist with a Doctor of Medical Sciences degree and nearly 40 years of experience. She’s helped deliver around 4,000 babies. Served over three years in the Ukrainian Armed Forces under the callsign “Svitlyachok” (Firefly).

I always knew that if my country went to war, I would join the army. During wartime, a doctor must help the wounded—that was just my default setting.

I served in one of the mobile hospitals, where we provided staged medical care to wounded, injured, and sick service members.

What stays with me most is the daily, quiet heroism of our defenders. People who had never planned to be soldiers, who weren’t part of the military before the war, stood up and went to defend the country—defend all of us—when it became necessary. And then there are the professional soldiers who’ve devoted themselves entirely to this cause. It’s an incredible feeling to stand beside them, to help.

I saved the first piece of shrapnel I removed from a soldier. You see, I used to deliver babies—that’s the highest concentration of life. A newborn is pure energy, the start of an entire life. But now, I was pulling something entirely different from a human body—something deadly, malicious. That was a turning point for me.

I kept that first piece of shrapnel. I don’t know why—maybe to remember.

Obstetrics and gynecology is a field where you rarely cross paths with patients again. But once, I was on duty for wound care, and a soldier came in. Turned out, exactly five years earlier to the day, I had delivered his wife’s baby. He recognized me and was stunned: “Is that really you?”

I’ve also seen on Facebook that babies I delivered ended up in different hospitals after being injured in the war.

I even delivered babies during the war. We were stationed next to a hospital that lacked essential staff—a surgeon, an obstetrician, and an anesthesiologist. So our medical team would often help them out. Twice, they brought in women in labor and called me in.

I remember one wounded scout—a small, skinny guy—who, I was told, had carried seven comrades off the battlefield. When he regained consciousness, he was distraught that he hadn’t saved his commander. But it turned out he had—he just didn’t remember. The commander was in our ICU, so I brought the scout to see him so he could know he had saved everyone.

That commander was twice the size of the scout. How did he carry him out? It was sheer strength of spirit—stronger than any physical power. There were many stories like that. On paper, they’re feats of heroism. But if you ask the soldiers, they’ll just say it’s part of the job.

When I reached retirement age, I stayed on another year. I couldn’t stop. When they brought in the wounded—covered in soil, burned, but unbroken—it was deeply motivating. Their resilience filled me with gratitude. It was for them that I served all three years and one month.

The eyes in the sky

Callsign Kafa (she/they), 24, is a drone operator and aerial intelligence analyst with the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

When the full-scale invasion began, I was 21, living and working in Germany. But there’s a broader context—I was born and raised in Crimea. So Russian imperialism is deeply personal for me. Even my call sign, Kafa, comes from the ancient name of my hometown, Feodosia.

On the day it all started, my father called me. My immediate thought was: What can I do? I helped organize a support system for Ukrainians in Berlin—volunteering at train stations, translating, and helping refugees. But soon I realized it wasn’t enough. I couldn’t just choose a privileged life abroad and close my eyes to what was happening. I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had to do something. I took responsibility—and six months later, I returned to Ukraine. Eventually, I signed a contract with the Armed Forces.

I joined the 93rd Mechanized Brigade “Kholodnyi Yar” and took part in the battle for Bakhmut. Later, I served in another unit as an aerial reconnaissance specialist and analyst, fighting in Kharkiv, Donetsk, and Zaporizhzhia regions.

I’ve experienced a lot—some of it tragic, some of it absurd. I remember we tried to rescue a sheep we’d seen regularly on drone footage. When it came time to change positions, I convinced the guys we should take the sheep with us—we couldn’t just leave it behind. So my comrade and I went to find it. Turned out, it wasn’t a cute little sheep—it was a massive ram, glaring at us. We tried to catch it, but quickly realized it wasn’t going to work. The ram ran off—and my comrades still tease me about it.

In my line of work, I don’t keep score of what we’ve destroyed. It’s not a competition. The key is consistency—doing your job every single day. Drone operators save infantry blood. That’s our main goal.

Why didn’t I stand aside? Because I don’t want anyone else to live under occupation. I don’t want our children raised under Russian culture. I don’t want another Ukrainian home to be touched by war.

Russia is the ultimate evil. And the best thing an individual can do in life is resist that evil. I just knew it had to be done. Every injustice must be met with resistance. Russia took my home—and it has to pay for that.

I think about home. About Crimea. I want to return and see the sea I grew up with again.

The preacher in a flak jacket

Callsign Ovsii, 53, is a military chaplain serving with the Ukrainian Armed Forces. A former journalist and religious leader.

Before the full-scale invasion, I worked in media for nearly 20 years—on television, even as an editor-in-chief. At the same time, I was active in religious work: I helped found the Islamic Cultural Center in Dnipro and later worked with the Religious Administration of Muslims of Ukraine.

In early 2022, my family and I already sensed that a major war was coming. We woke up to the first missile strikes. By 9 a.m., my son and I were enlisting in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. I had no doubts—when there’s aggression, it must be met with resistance.

I have a degree in history, so I knew: Russia has always tried to swallow Ukraine. Every time, it’s been a tragedy for our people. If we don’t resist, we’ll be wiped out. So I didn’t even question whether to fight. When your loved ones, your homeland, your entire nation are under threat—what do you do? You fight back.

I’m Muslim, and in Islam, questions of war are resolved more clearly than in Christianity. It’s written plainly: if someone attacks you, you are obligated to resist evil.

Over these nearly four years, I’ve lived what feels like an entirely separate life in the military. There have been assaults, losses, and deep friendships. We support local communities where our unit is stationed—helping a school and the children who study there.

I often remember when we decided to go fishing just a few kilometers from the front. We found a tiny pond, maybe a meter deep, made makeshift fishing rods, and cast our lines. Soldiers would drive by on their way to and from the front lines, laughing and spinning their fingers at their temples—“What are these guys doing?” We didn’t catch a single fish.

As a chaplain, the religious aspect is just part of my work. Most often, soldiers come for support. Family issues, interpersonal conflicts—you name it. I act more like a psychologist. Once, my comrades asked me to explain the Israel-Palestine conflict. I gave them a full-hour lecture—it’s a centuries-old struggle. We used to have real philosophical debates in the mess hall—cooks would stay after hours just to talk. But now, with the enemy targeting even small gatherings, we have to avoid that.

What keeps us going after nearly four years of war? The understanding that we can’t stop. Like a runner in Antarctica—if he stops, he freezes and dies. If we stop, we’re finished. It’s a simple choice: either the imperial enemy dies, or we do.

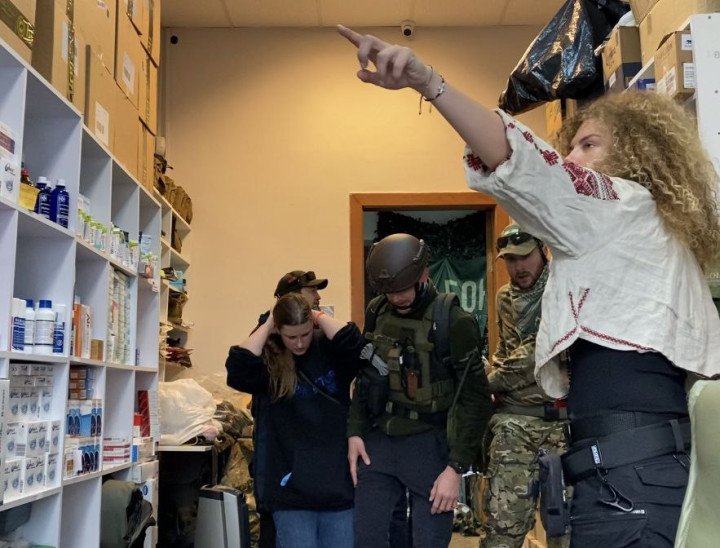

The architect of aid

Oresta Brit, 35, heads the BON Foundation, a Ukrainian nonprofit providing humanitarian aid to civilians and families affected by the war. Graduated from the Sorbonne with a degree in public relations.

In July 2014, when Russia invaded the east of Ukraine, I traveled to the Luhansk region with soldiers from the 12th Battalion. At a checkpoint, the soldiers said, “Let the volunteers through.” That was the first time I heard the term used about me. It turned out we were among the first volunteers to arrive in that region.

Before the full-scale invasion, the BON Foundation was more of a side project. After February 24, 2022, it became my full-time profession—an expansive platform for delivering aid and saving lives. I built the foundation for myself, my family, and my future children. I sincerely hope that one day its scale will shrink, and Ukraine will become a country that no longer needs massive charitable organizations. That charity will simply be a noble Ukrainian tradition.

We began preparing a few months before the invasion—buying generators, sand, bags, and other supplies to build defensive structures in Luhansk and Donetsk regions. When the full-scale war began, I realized some of that aid hadn’t reached the military—“Nova Poshta” depots we sent it to had been occupied. Thankfully, they managed to save the cargo, and three months later, after the liberation, it was delivered to the troops.

When the invasion began, I was in Lithuania setting up a branch of a foundation to legally receive humanitarian aid. I immediately returned to Kyiv with the first aid convoy we organized in Lithuania. We had to set up support points around Kyiv and coordinate BON and its volunteer groups—over 150 people at the time—handling evacuations, cooking hot meals for checkpoints and shelters.

As an official and recognizable foundation, we could travel between checkpoints in Kyiv—divided into sectors—under escort from police, territorial defense, and the military, delivering aid directly to those in need. This network operated until Russian forces were pushed out of the Kyiv region. Afterward, we focused on helping the liberated areas and retrieving bodies.

Our reported aid totals about $10 million. The foundation works with civilians, while the affiliated NGO works with the military. 100% of donations go directly to aid; our administrative costs are covered by partner organizations and friends. We’ve helped over a thousand families of fallen or missing defenders, and distributed emergency aid in the liberated areas—though exact figures there are hard to track. Our military assistance figures are detailed but classified.

Why do I do this? In my family, lack of empathy is seen as a sign of personal decline. When your country faces a catastrophe of this scale, how can you stand aside?

In the early years, I tried to tell foreigners more about Ukraine, our struggle, the cyclical nature of history, and the consequences of inaction. Today, I urge them to learn from our experience. Reality shows they’ll need it. We’re ready to share our hard-earned knowledge of defense and resilience. That’s one of BON’s missions.

Over the past year, foreigners have finally begun to understand this—and actively seek our expertise. Through our courage and strength, we’ve gained—and now share—unprecedented knowledge of resilience.

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)