- Category

- Opinion

If We Stop Resisting and Russia Occupies Ukraine, We Simply Will Not Exist

Ukrainians continue to fight against Russia for even the slightest chance that their children might one day live in a peaceful, democratic society—that is, to have the freedom to live without fear of violence and with a future to look forward to. Because the fastest way to stop the war is to lose it. But then, there will be no peace.

It’s the fourth year of the full-scale invasion—one that, according to both Russian and Western analysts, was supposed to end in four days. Ukraine chose not to play the role of the perfect victim, but to resist.

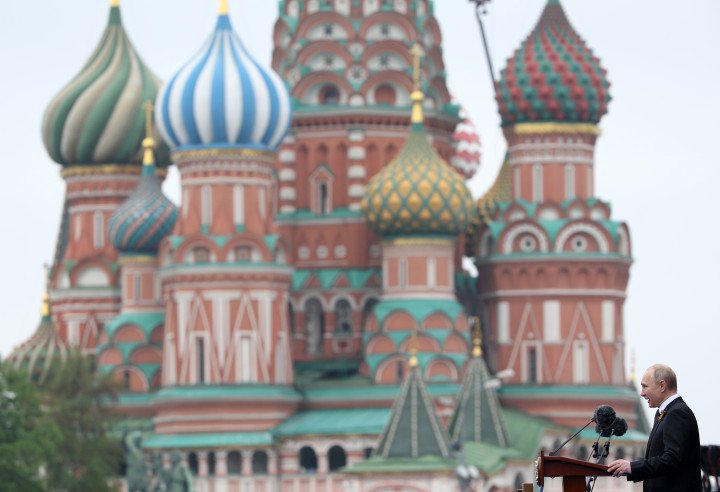

Putin didn’t launch the full-scale invasion just to seize another piece of Ukrainian land. It’s naive to think that Russia has sacrificed hundreds of thousands of its soldiers just to occupy Avdiivka or Bakhmut. Putin launched the full-scale invasion to occupy and destroy all of Ukraine—and then move further. His logic is historical: he dreams of restoring the Russian Empire. That’s why people in other European countries live in relative safety, only because Ukrainians continue to hold back the advance of the Russian army.

The truth is that the outcome of this war will determine what Europe—and the world as a whole—will look like. The decades of freedom that followed the fall of the Berlin Wall could easily give way to decades of mere survival. So when I’m asked how Ukrainians envision achieving a just and lasting peace, I always ask that the question be framed correctly. This is not just Ukraine’s problem—not when a permanent member of the UN Security Council tramples the UN Charter, launches a war of aggression, and tries to redraw internationally recognized borders by force.

You can’t build paradise—even if you’re an island—when part of the world is still bleeding.

Human rights lawyer, head of the Center for Civil Liberties, Nobel Peace Prize recipient (2022)

Many things in this world don’t stop at borders. And it’s no coincidence that I want to speak about one of those things: the role of culture in achieving a just and lasting peace.

Russia’s war is genocidal

Putin openly claims that there is no Ukrainian nation, no Ukrainian language, no Ukrainian culture. For years, we—human rights defenders—have been documenting how these words translate into horrific practice.

In the occupied territories, Russians are physically eliminating active members of society—mayors, journalists, children’s authors, priests, musicians, teachers, entrepreneurs. They ban the Ukrainian language and culture. They loot and destroy Ukraine’s cultural heritage. They conscript Ukrainian men into the Russian army. They send Ukrainian children to so-called “re-education” camps, where they’re told they are not Ukrainian but Russian—that their parents or relatives have abandoned them, and that they will now be placed in Russian families who will raise them as Russians.

Russia tries to portray our resistance to occupation and the destruction of Ukrainian identity as actions that “undermine peace.” So we are forced to constantly explain things that are obvious to us—but not obvious to the world. Peace does not come when a country under attack stops defending itself. That’s not peace—that’s occupation.

Occupation is the same war, just in a different form. Occupation is not simply the replacement of one flag with another. It is forced disappearances, rape, torture, the adoption of your children by the aggressor, the denial of your identity, filtration camps, and mass graves.

When Putin told Trump in Alaska that he would wage a war to eliminate its “root causes,” those root causes are our very existence. Because to destroy a national group you don’t have to kill all its members. You can forcibly erase their identity, and the entire national group will disappear.

We cannot stop resisting Russian aggression. If Russia occupies Ukraine, we simply will not exist.

Countries that grow tired of proving their identity disappear.

Human rights lawyer, head of the Center for Civil Liberties, Nobel Peace Prize recipient (2022)

The war is changing how Ukrainians are perceived in the world

Every nation is a narrative—a story it tells about itself. But for centuries, Ukrainians lived in the shadow of the Russian Empire. And empire is not just about controlling land, resources, and people. It’s about controlling the knowledge—about how we speak about each other. It’s about the power to name things.

We entered this full-scale war as a society without context. People on other continents knew only one thing about our part of the world: that it was “Russia.” Our history wasn’t written by us. We are a country whose literary classics haven’t even been translated. Even today, I still get asked whether Ukrainian language is actually different from Russian.

In response, I often tell the story of a painting by [Edgar—ed.] Degas at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It depicts girls in national dress. For many years, the painting was titled “Russian Dancers”—but the girls are wearing vyshyvankas and flower wreaths, traditional Ukrainian clothing. For years, Ukrainian art historians sent letters asking for the painting to be renamed or at least annotated. No one listened.

Only after the full-scale invasion did the Met change the title. It’s now called “Dancers in Ukrainian Dress.” The museum administration probably still believes they’re Russian dancers who just happened to be wearing Ukrainian costumes—but still, it’s a meaningful shift. Ukraine is beginning to appear on the world’s mental map. Sadly, at a very high cost.

We are a vivid example that a country’s agency is not measured by its national income or possession of nuclear weapons, but by the willingness of its citizens to defend their freedom. The freedom to be an independent state, not a Russian colony. The freedom to preserve one’s identity, not to re-educate Ukrainian children as Russians. The freedom to have a democratic choice—the ability to build a country where every person’s rights are protected, where power is accountable and transparent, where courts are independent, and where the police neither beat nor disperse peaceful student protests.

At the same time, we see that interest in our country is gradually fading. And that’s natural. This war is far from the only hot spot on the planet. The humanitarian crisis and military conflict in Sudan have been ongoing for over 20 years. Millions of women in Afghanistan are forbidden to speak in the presence of men. A third of all imprisoned writers in the world are held in Chinese prisons. And right now, many people across different parts of the world are fighting for their freedom and human dignity. Only a few make it onto the front pages of the global media.

If Ukraine is perceived solely through the lens of Russian crimes and victimhood, while Russia is seen through the prism of its “great culture,” we will lose.

Human rights lawyer, head of the Center for Civil Liberties, Nobel Peace Prize recipient (2022)

Images of bodies on the streets of Bucha or the destroyed drama theater in Mariupol can easily be replaced by images of other victims. But we can be interesting beyond our pain and suffering. People can grow tired of sympathy, but they cannot grow tired of inspiration.

Culture is a legitimization of the state

Culture as an autonomous phenomenon emerged relatively recently. Before that, culture was part of church life or served monarchs and helped strengthen their power. The process of separating culture from authority stretched over several centuries.

For some reason, today, art “outside politics” is often understood as art free from anything that causes discomfort or prompts decisive action. But historically, it meant that art no longer serves the ruling elites. Our theme for the coming years is the question of war and peace. If we talk only about anything else, we will be out of step with the reality of our time.

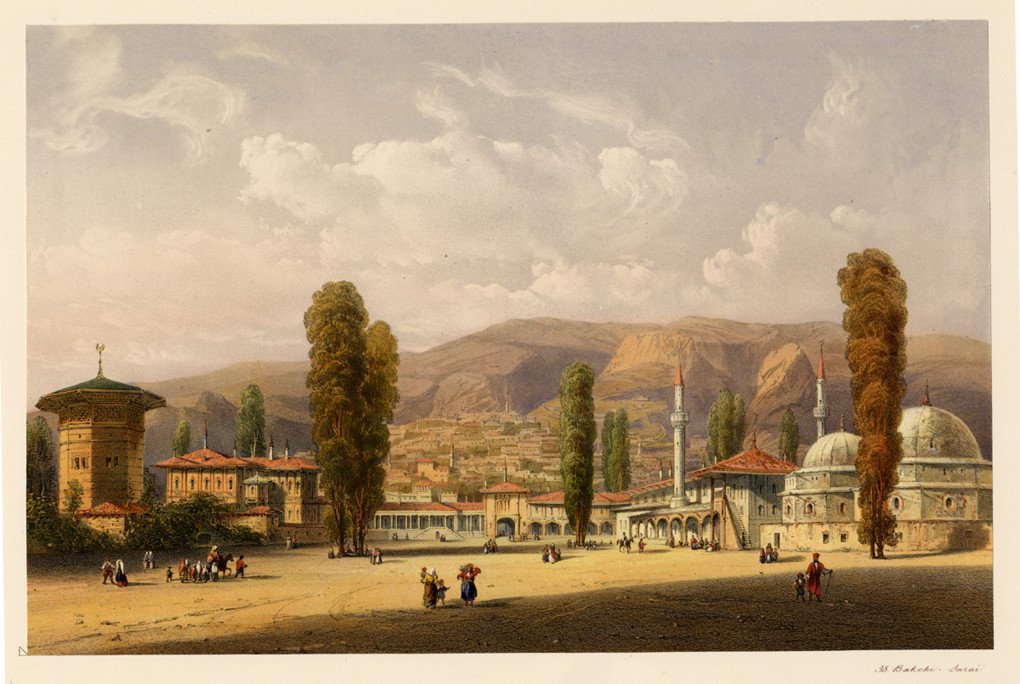

Culture is also the continuity of experience between the present and the past. And this continuity has often been violently broken in our case. So it is our task to restore these breaks and to give voice to those whom the empire erased from history. The destruction of the Khan’s palace in Bakhchysarai is not just an act of barbarism but a deliberate policy. The archaeological sites in Crimea stand as silent witnesses that Russian rule does not originate from ancient times. More than that, they compel us to understand that this rule is temporary.

Culture is not only about works of art or mass-produced products; it is about meanings passed down from generation to generation, shaping established patterns of behavior in society. For a long time, the problem of our society was its inability to call evil by its name. We lived in a country where streets bore the names of the executioners of Ukrainians. Monuments stood in honor of these executioners. And this bothered almost no one.

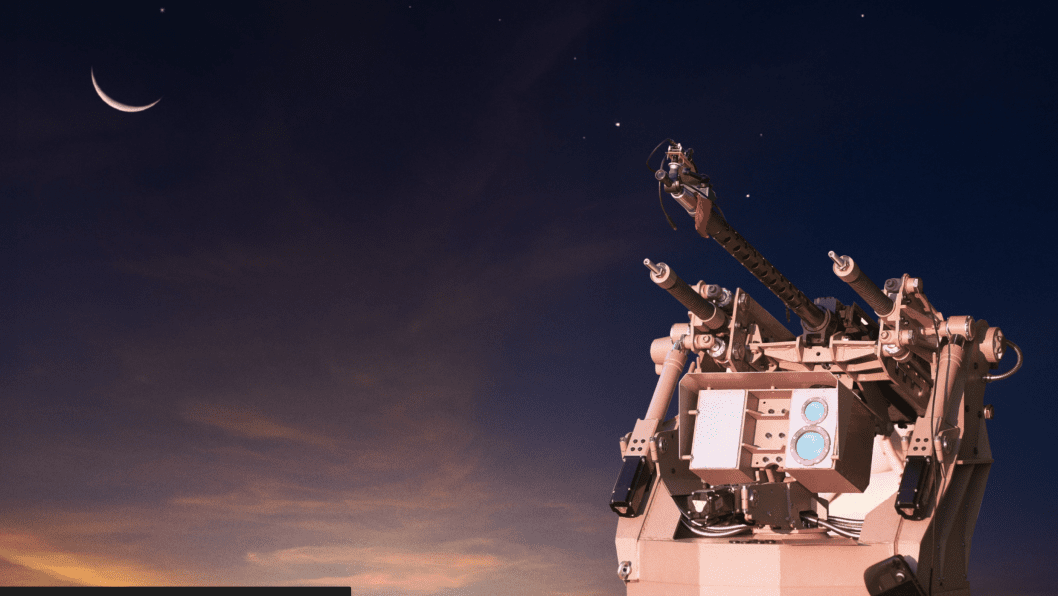

This war has a value dimension. It is not a war between two countries, but a war between two systems—authoritarianism and democracy. Each corresponds to its own set of values.

And we fight not only because we are not them, but because we defend values incompatible with the Russian way of life.

Culture creates and promotes meanings

Like many in Ukraine, I was born on the ruins of the Soviet Union. But through this struggle, we have become Europeans. Because Europe is not about geography—it’s about values. Ukrainians are rethinking the values of freedom and security, which Western societies have long taken for granted.

First, for us, freedom is not just a value of self-expression—paradoxically, it is a value of survival. We would not have survived or emerged as a nation if, over the centuries, we had not stubbornly pursued freedom.

Second, we do not see freedom and security as opposites. We need freedom for security, and security for freedom. Because when we lose one, we inevitably lose the other.

Third, for us, the state is an environment for existence—not just a set of services. It is what preserves our identity.

You can love something even if it’s not perfect—and that’s exactly why even the imperfect must be defended and preserved.

Human rights lawyer, head of the Center for Civil Liberties, Nobel Peace Prize recipient (2022)

Fourth, we believe that the efforts of ordinary people matter. We’ve never had the luxury of relying on efficient state institutions, so self-organization and grassroots agency are our vital force. The question is: how do we talk about all of this? Blame, fearmongering, or hysteria don’t work.

I often use what I call the “mirror test”—reminding myself how Ukrainian society behaved before the full-scale invasion. The only right tone of voice is dignity.

I once recorded the testimony of Ukrainian philosopher Ihor Kozlovskyi. He spent 700 days in Russian captivity. Before that, I had interviewed hundreds of people who told me how they were beaten, raped, locked in wooden boxes, had their limbs cut off, or electric shocks applied to their genitals. One woman told me how her eye was gouged with a spoon. So by that point, there was very little left that could shock me.

But Ihor mentioned a detail that seemed insignificant for legal evidence—and yet it struck me. He was describing his daily life in solitary confinement. It was a basement cell, previously used in Soviet times to hold prisoners on death row. There were no windows, no sunlight, barely any air—it was hard to breathe. Sewage leaked across the dirty floor. Rats would crawl out of the drain. And this man—a philosopher known across the country—told me how he gave philosophy lectures to those rats, just to hear the sound of a human voice.

Legally, Ihor Kozlovskyi was a victim—he was abducted, held in inhumane conditions, and tortured to the point that he had to relearn how to walk. But he always said that none of this gave him the right to live or see himself as a victim. Because the foundation of our existence is dignity, not victimhood.

And dignity is action. It’s not just about feeling responsible for what happens—it’s about doing the right things to change it. Dignity gives us the strength to fight, even in unbearable circumstances.

We are not hostages of circumstance—we are participants in this historical process. And the honest answer to the question of a just and lasting peace is that it’s still too early to draw final conclusions. But already today, we must clearly define what peace means to us—and what victory means in this war.

A return to our state borders is not victory—it is the restoration of international law. Victory is the achievement of our historical goals: a final break with the “Russian world” and a return to European civilizational space—with its values and meanings. And those who plan for the long term are the ones who win.

-9e5ee659005c07077a59186b7eebd750.jpg)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)

-da3d9b88efb4b978fa15568884ef067f.jpg)

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-f3bede69822b36ac993a6cd5b65014f9.png)