- Category

- War in Ukraine

What Happens to a Kid Abducted by Russia? Survivors and Detention Camp Maps Reveal a System of Indoctrination

Russia wages war on Ukraine not only with tanks and missiles, but with paperwork, orphanages, and name changes targeting a generation of young Ukrainians—abducting them, militarizing them, and preparing them to fight against their own home. How does Russia transform stolen Ukrainian children into tools of its war and where are they now?

Nearly 20,000 Ukrainian children have been forcibly transferred to Russia or Russian-occupied territories since Russia started its full-scale invasion. There, they are subjected to brutal “reeducation” aimed at erasing their language, culture, and roots.

Where the children are taken

Thanks to the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s Bring Kids Back UA initiative, just over 1,300 children have been returned so far. Drawing on intelligence gathered by Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) and the Bring Kids Back UA team, this report reveals where these children are being taken, the conditions they are subjected to, and how the Russian state is systematically working to erase their Ukrainian identity.

Russia calls its kidnappings an “evacuation,” “humanitarian aid,” or “rescue.” International law is clear: deportation and forced displacement are war crimes.

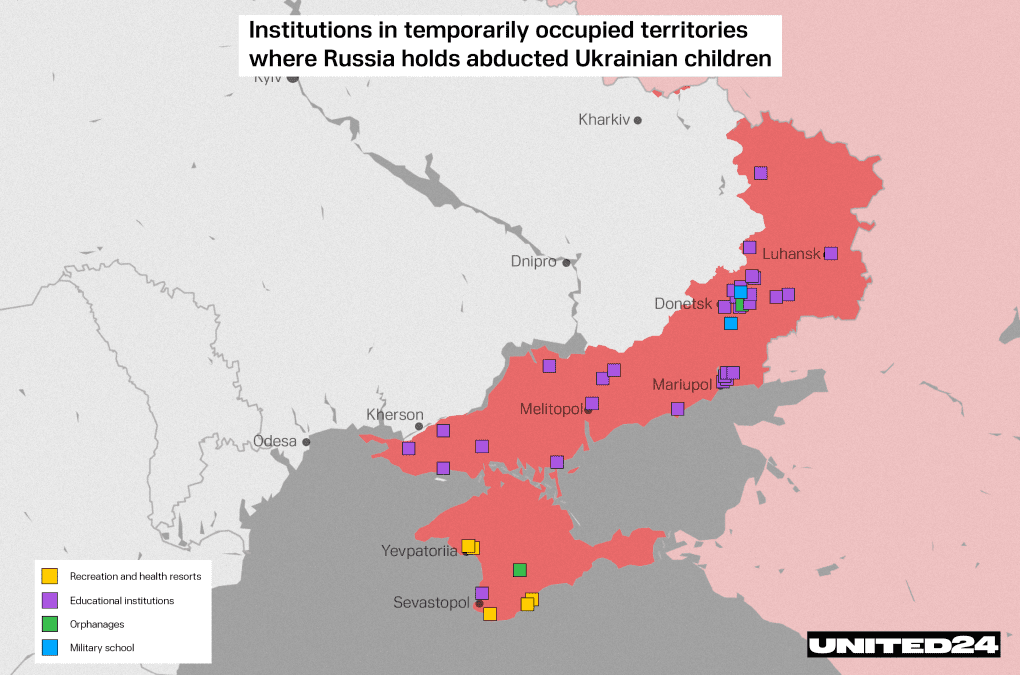

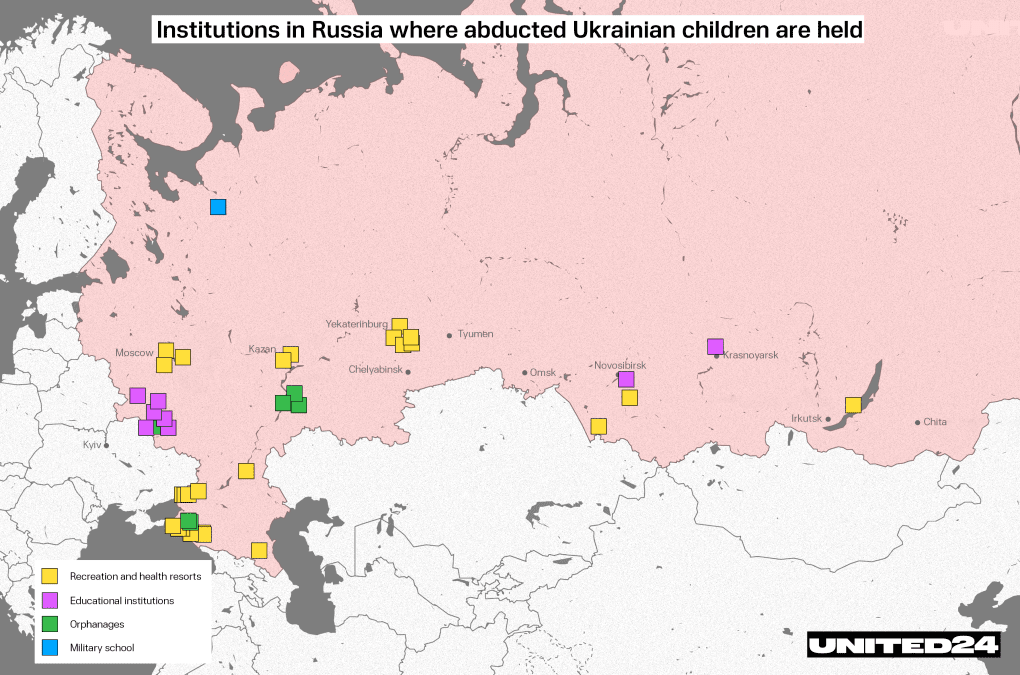

The SBU has identified over 150 locations where Russia is holding or has relocated abducted Ukrainian children, including families involved in illegal adoptions. These are around 40 camps, over 40 adoptive families, more than 50 educational institutions, and several Russian state-run facilities—spread across Russia and the temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine.

These forced relocations are part of what human rights groups call a state policy of Russification. Children are placed in camps or foster families, issued Russian passports, and compelled to forget their heritage. Some are enrolled in military schools, others are sent deep into Russia, given new biographies as if their pasts never existed.

Additionally, Russia illegally took at least 2,219 Ukrainian children to Belarus, where many are undergoing “re-education,” the Regional Center for Human Rights 2024 report says. Teenagers are fed propaganda claiming that Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories rightfully belong to Russia and are told fabricated tales of Ukrainian atrocities. These “Russian world” narratives are embedded in Belarus’s school system, starting as early as elementary education.

It’s still unclear how many of these children—if any—have been returned. Belarus actively hides their whereabouts and identities, making tracking nearly impossible. The RCHR, ZMINA, and Freedom House report at least 18 indoctrination camps for Ukrainian youth are currently operating inside Belarus.

In March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Russian leader Vladimir Putin and Children’s Rights Commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova for their role in the systematic deportation of Ukrainian children. But the crimes continue to this day.

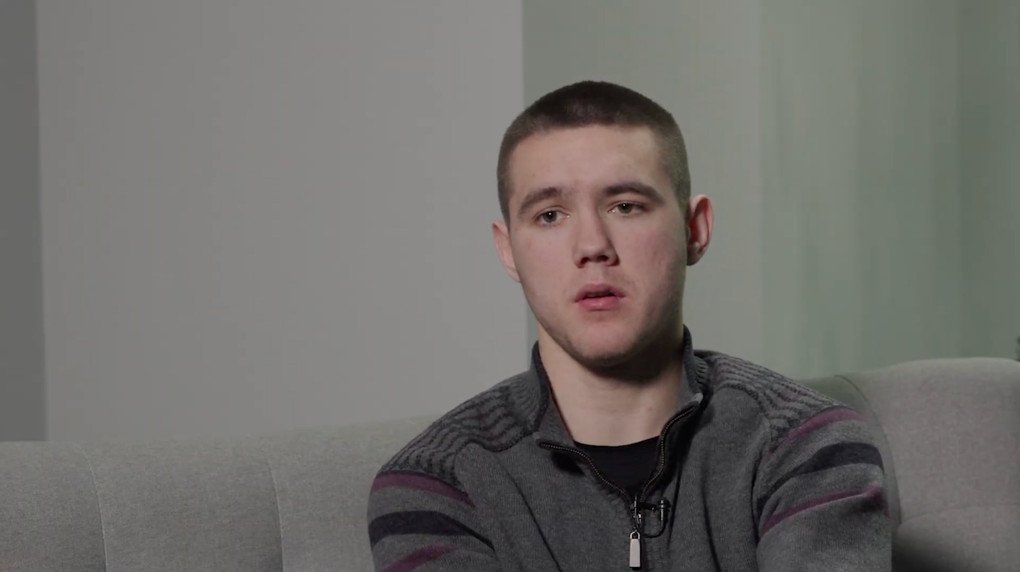

Artem, 19

“When the full-scale war started, I was 16. I lived in a village with my mom and dad. When the first explosions happened, we ran to the basement under my parents’ workplace and spent the night there. Then, the Russian soldiers arrived. They stayed in the village for three and a half months.

One day, the soldiers came to our house. They said a weapon had gone missing and were looking for ‘partisans.’ Even though they found nothing on my father, they beat him in front of us and took him away. They said he’d be back soon, but he was gone for 33 days. He later told us he was tortured with electric shocks during interrogations.

I continued studying online in secret. I was just about to receive my 9th-grade certificate.”

Tools of assimilation and abuse

Artem and his parents took a serious risk. In such cases, Russian puppet authorities in occupied Ukrainian territories threaten parents with fines, loss of parental rights, or arrest if they refuse to send their children to Russian-run schools or if their children study remotely under the Ukrainian curriculum.

Schools themselves became instruments of control. Children’s phones were checked for pro-Ukrainian content. In Mariupol, Ukrainian textbooks were burned in schoolyards, and teenagers were arrested for singing the national anthem. All of this is part of a vast system of Russification and cultural erasure disguised as “rescue.”

Illia, 12

“I was nine when it all started. We lived in Mariupol: me, my mom. I loved school and my friends. We had a beautiful home.

Then the explosions began. A missile hit our house, and we couldn’t live there anymore, so we went to a neighbor’s. But that night, there was another blast. I was hit by shrapnel. My mom was hit in the forehead. We buried her in the yard.

Then the Russian military came and ordered us to leave. That’s how I ended up in Donetsk. I had several surgeries there. The first one, without anesthesia, to remove a fragment.

They made me learn to write in Russian. One doctor told me I shouldn’t just say ‘Glory to Ukraine’ anymore, but ‘Glory to Ukraine as part of Russia.’”

Then one day, my grandma saw me in a propaganda hospital video. She managed to come and take me back—we arrived in Kyiv on my birthday. We didn’t celebrate—I was unwell, and doctors removed four more pieces of shrapnel. But now I want to become a doctor myself.”

Language erasure and re-education

Illia’s story is not just one of personal loss — it reflects a broader Russian tactic. The methods of abducting Ukrainian children include:

Killing or separating parents during filtration operations;

Removing children en masse from institutional care facilities;

Stripping parental rights under false pretenses;

Forcing parents to sign consent forms allowing their children to be taken to so-called “recreation camps” for a few weeks, from which children are never returned.

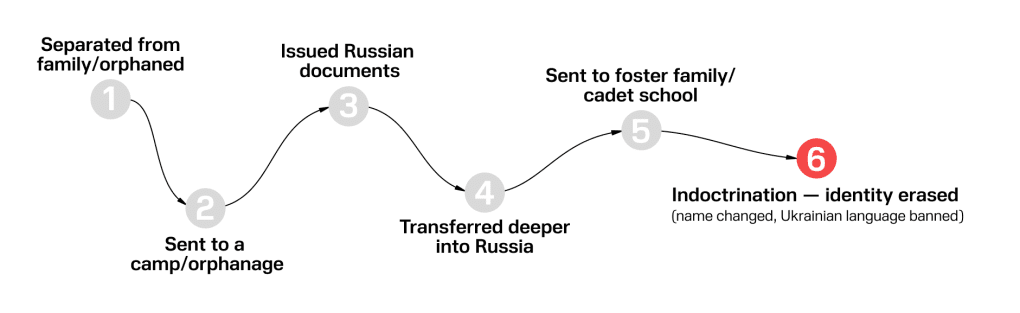

This is what Russia’s process of indoctrinating Ukrainian children often looks like:

Valerii, 19

“I was 16 when the Russian occupation started. Russian soldiers entered our village, acting arrogantly, like we owed them something. They handed out ‘humanitarian aid,’ filmed it, and made it seem like people welcomed them. But no one trusted them. We avoided the village center and rode bikes to get bread—quick in, quick out.

They offered to send kids to ‘camps,’ but we all heard what happened—kids left and didn’t come back. Or if they did, they were changed—they left normal, came back totally brainwashed.

We needed an ambulance once, but you couldn’t get one without Russian documents. So we had to agree to get them.”

Children separated from their families often end up in closed institutions—special schools, camps, or orphanages—where reeducation awaits. Russian officials openly declare their intent to “correct pro-Ukrainian attitudes.”

“At first, the children spoke badly of the president [of Russia], sang the Ukrainian anthem, and expressed negative feelings,” said ICC-wanted Maria Lvova-Belova, commenting on the “reeducation” of Ukrainian children. ”Eventually, that negativity turns into love for Russia.”

Mykhailo Podolyak, advisor to Ukraine’s Presidential Office, responded: “According to her [Lvova-Belova], abducted children from Mariupol curse Putin and sing the anthem. ‘We’ll fix that,’ she promises. They invaded, destroyed their city, killed their parents, and now strip away their identity. That’s what genocide looks like.”

A report by the New Lines Institute in Washington and the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights in Montreal says Russia is violating two articles of the 1948 Genocide Convention. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has also demanded the safe return of Ukrainian children forcibly transferred to Russia or territory it temporarily occupies, as well as punishment of those who carried it out at all levels.

In some cases, the consequences are irreversible. In January 2024, 18-year-old Oleksandr Yakushchenko, abducted by Russians from Kherson and placed in a Russian foster family, died by suicide in Krasnodar Krai.

Valerii, 19 (continued)

“At school, the Russian flag was everywhere. They made us watch military films, tried to make us admire the Russian army. Soldiers came in to ‘inspire’ us.

Everyone had to attend the flag-raising. If you didn’t, they took your photo and your name. Later, they came to your home and beat you. My friend was taken to the basement eight times—just for skipping.

They forced me to sign a draft summons. A Russian soldier with a gun was standing right beside me, looking at me like I owed him a hundred bucks.

That evening, my mom called: ‘There’s a chance to escape.’ At the Russian border, they questioned me—name, surname, mother’s birthday. I forgot the exact date — they started beating me with batons. Said, ‘You’ll be sent straight to the meat grinder.’ After two hours, they let me go.

After we left, the Russians moved into our home.”

The children’s gulag

Children from occupied Ukrainian regions are systematically transferred to Russia and enrolled in Russian schools. Their education system is now saturated with military propaganda, and some Ukrainian children are placed in outright militarized institutions like cadet academies, with the most notorious one being the ultrapatriotic military organization Yunarmia (Young Army or Youth Army), which indoctrinates children to instill loyalty to the Russian state and its military agenda. Just from the temporarily occupied Zaporizhzhia region, Russia has recruited approximately 1,000 children into the Yunarmia. There, they rise at 6 a.m., wear uniforms, sing the national anthem, and train with Kalashnikov rifles.

Satellite imagery analyzed by Portuguese company Hala Systems has recently revealed 136 such facilities where Ukrainian children are held. The network of detention camps for Ukrainian children is reminiscent of the Soviet gulags.

Ukraine had also identified camps for forced “reeducation” in Belarus, occupied Crimea, and even Russia’s Far East. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe OSCE confirmed that youth in these environments are subjected to targeted indoctrination.

Artem, 16 (continued)

“I studied secretly in a Ukrainian online school. To get my 9th-grade certificate, I had to go to Kupiansk. But Russian troops seized all of us, loaded us into a bus, and took us somewhere.

At first, we thought it was just another school. But then we realized it was an orphanage.

I was there for six months. We shared a room with nine boys, slept on sagging metal beds, no bedding — just blankets. Terrible sanitation. Every day, we ate barley, stew, strange compote, and crackers. I can’t eat barley anymore—it makes me sick.

Walks were 5–10 minutes long and supervised. Ukrainian was banned, but we spoke it anyway.

Classes were in Russian. When officials visited, we had to wear Russian uniforms and sing the anthem. They handed out printed lyrics — I threw mine out. They threatened to send me to a foster family.

Then I found out my classmate Dima had a phone. He let me call my mom. When she heard my voice, she cried. Four days later, she came and got me.”

Despite the dangers, economic hardship, and humanitarian crisis, 91% of Ukrainians value freedom above all, followed by security (79%), justice (76%), and dignity (71%), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) study reveals.

Vladyslav, 19

“When the war began, I was 16 and living in Kherson. The college was operating under the Russian curriculum, so I stopped attending. One morning, when I was home alone, three Russian soldiers knocked on our door. One was armed. They told me to pack and come with them.

They took me to the river port, where other children were gathered. They said we were going to Crimea. We boarded a ferry, then 17 buses. It felt like a convoy.

At the Crimean border, they held us for two hours. A woman gave us entry papers, but they only had an entry date, not an exit date. I thought: How do I go home?”

“Vacation” with the taste of a prison camp

Behind the façade of “sanatoriums” and “recreation camps” lie institutions where children are not healed, but broken. These are places where loyalty to all things Russian is instilled through humiliation, fear, and propaganda. In Vladyslav’s case, this meant isolation, psychological abuse, and filmed humiliation—all under the banner of a state claiming to be a savior.

Camps became ideological training centers: war briefings, letters to soldiers, drill exercises, all meant to turn Ukrainian children into citizens of the aggressor state.

“They are infants, teenagers, and so many young lives that should not be scattered across Russia, taught to hate Ukraine, but instead should be with their loved ones, in their own country,” said Zelenskyy. “Forcing children from one nation into another and erasing their identities is clearly a genocidal practice.”

This kidnapping and coerced adoption program “was initiated by Putin and his subordinates with the intent to ‘Russify’ children from Ukraine,” Yale University’s Humanitarian Research Lab reported. It details how Russia’s Aerospace Forces, under the direct command of Putin’s office, flew multiple groups of children from Ukraine on military transport planes.

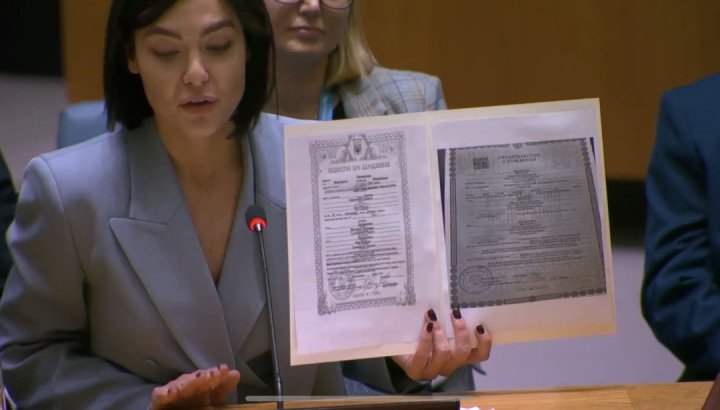

Some children were separated from their siblings in the course of illegal adoptions. Others had their names and citizenship changed. One case involved Russian politician Sergei Mironov, who took 10-month-old Margaryta Prokopenko to Russia under the pretense of “medical examinations and rehabilitation.” Later, the girl’s name and citizenship were changed—within the pro-Putin politician’s family, she became “Marina Mironova” with her place of birth altered from Kherson, Ukraine, to Podolsk, Russia.

Another abducted child, 7-year-old Oleh Pskovskyi from Donetsk, was “adopted” by a Russian paratrooper, Viktor Filonov, accused of killing civilians in Ukraine, including in Bucha.

Russia plans another mass deportation in summer 2025—more than 50,000 Ukrainian children from the occupied Donetsk region, under the false pretext of “vacation,” Ukraine’s National Resistance Center reported. The children will be subjected to ideological programs promoting the “Russian world” — part of a deliberate strategy to erase Ukrainian identity.

During negotiations in Istanbul on June 2, the Ukrainian delegation handed the Russians a list of Ukrainian children whose return they demanded. The head of the Russian delegation, Vladimir Medinsky, responded: “Don’t put on a show for bleeding-heart European old ladies,” The Economist correspondent Oliver Carroll reported.

Vladyslav, 19 (continued)

“They brought us to Camp Druzhba . Out of 17 buses, only 3 or 4 entered—no idea what happened to the rest.

The security chief read the rules: sing the Russian anthem, raise the Russian flag, follow the schedule.

I hated it. I pulled the Russian flag down and hung my underwear in its place, then tossed the flag in the trash. They gave me two choices: a psychiatric ward or five days in isolation. I chose isolation.”

The SBU report we obtained reveals where abducted Ukrainian children are being sent. The list includes an orphanage for children with brain disorders in Krasnodar Krai and a psychiatric hospital in occupied Crimea. It seems Russia hasn’t let go of its Soviet-era practice: silencing dissent through punitive psychiatry.

“Then they moved me to another camp in Luchyste village. We kept asking when we could go home. They said: when Russia retakes Kherson.

Next, we were transferred again to a naval academy in Lazurne. The place was completely locked down. I was there for five and a half months.

One day, my mom called my friend’s phone. She promised to come get me. When she arrived in Crimea, they detained and interrogated her. Then they came to me, said there was nothing for me in Ukraine, that I’d live in a basement.

But I wanted to go home.

They held my mom for three days. Eventually, they let her take me. Before leaving, we had to record a staged video about our ‘future plans in Russia.’ We agreed—just to get out.

A week later, we were back in Ukraine. Home.”

While as of spring 2025, the Bring Kids Back UA initiative has managed to return about 1,300 children, at least 19,546 are known to have been deported or forcibly relocated—many deep into Russia. Another 1.6 million Ukrainian children remain in temporarily occupied territories.

These children now answer to new names, are forced to sing a foreign anthem, and have had their life stories rewritten and their childhoods stolen.

Every story here is real. We only know them because these children have managed to make it back.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-ca1a63b87c648c14784932e034e42964.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)