- Category

- War in Ukraine

Is the Modern-Day Nuremberg Tribunal for Putin and Other Russian War Criminals Finally About to Happen?

What would a tribunal for Vladimir Putin look like? It wouldn’t be just about him. It would be about hundreds of Russian commanders, soldiers, propagandists, and officials who enabled and committed atrocities across Ukraine.

Europe is expected to formally endorse the creation of a Special Tribunal on May 9 to prosecute Russia for the crime of aggression, with the primary goal of holding Putin accountable. Discussions on a special tribunal for Russia have been ongoing since 2022, as no existing international court currently has jurisdiction over the crime of aggression. Momentum picked up in early 2025: at the 13th meeting of the Core Group on February 4, member states finalized a draft statute and agreed to establish the tribunal. Technical work concluded in late March, producing three key documents: a bilateral agreement with Ukraine, the tribunal’s statute, and a management agreement.

But there are hurdles.

"The Special Tribunal will not try Vladimir Putin in absentia as long as he is president of Russia," said a representative of the European Union in Brussels. The same applies to Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov.

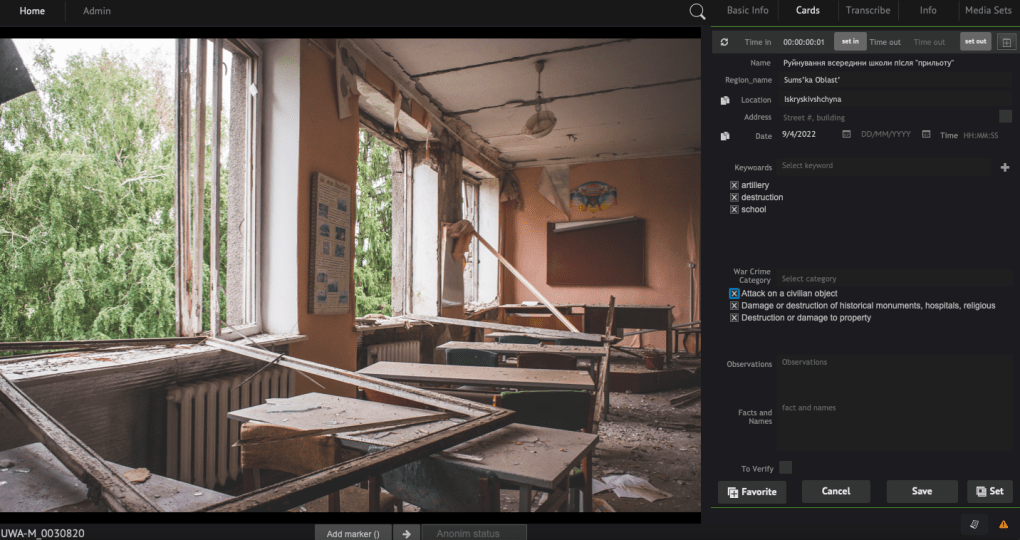

While the Special Tribunal targets the crime of aggression at the highest political level, a parallel effort in Ukraine is focused on exposing the full machinery of Russian terror.

The Ukrainian-led Tribunal for Putin initiative is building what could become the legal case of the century, with nearly 85,000 documented war crimes and nine submissions to The Hague. Despite the name, the initiative focuses on all those responsible for war crimes in Ukraine, not just Putin.

To understand how this effort works, we received exclusive input from the human rights organizations Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group and Truth Hounds, as well as the Ukraine War Archive, which preserves critical evidence of Russian atrocities.

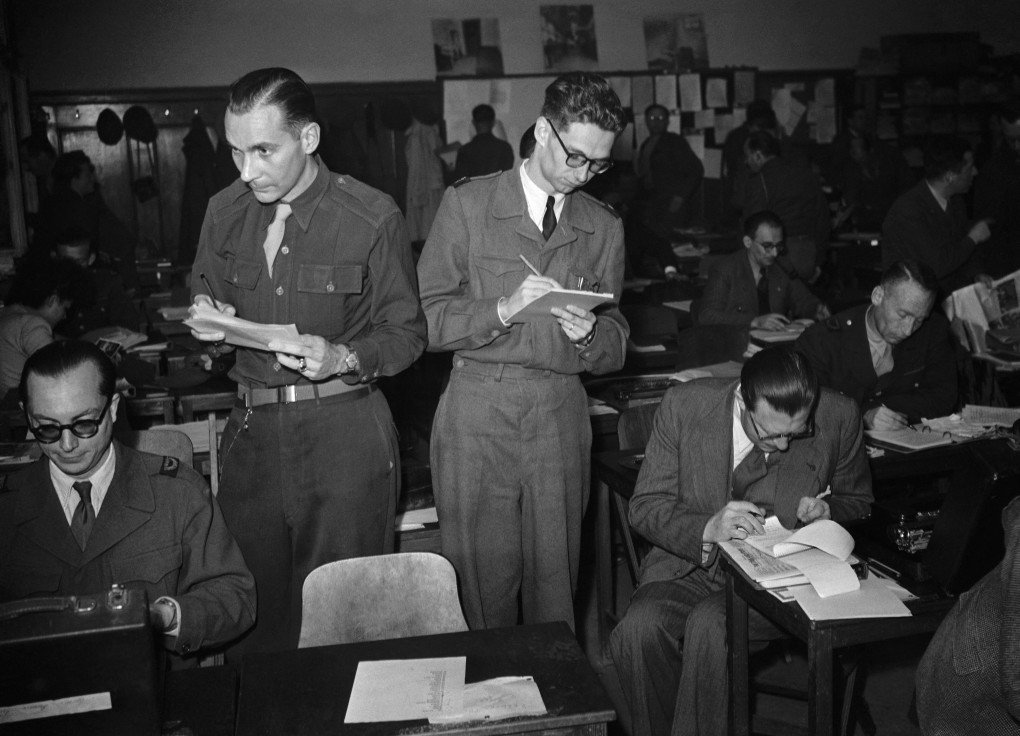

The Nuremberg Trials

After World War II, Allied investigators combed through the ruins of Europe gathering everything the Nazis left behind: execution orders, transport lists, mass shooting footage, and survivor testimonies. That evidence became the backbone of the Nuremberg Trials (1945–1946), where leaders of the Third Reich were prosecuted for crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

But the legal foundation for Nuremberg was laid even earlier. In 1943, the Declaration of Atrocities promised that perpetrators would be returned to the scenes of their crimes and judged under the laws of liberated countries, making justice visible, immediate, and real.

Now, nearly 80 years later, Ukrainian human rights defenders are documenting war crimes across cities devastated by Russian attacks: mass graves, tortured civilians, intercepted orders. Their evidence feeds into the Tribunal for Putin initiative—an alliance of legal experts, NGOs, and advocates building cases for crimes of aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

This grassroots effort complements a broader international push to revive Nuremberg’s legacy. With Europe expected to endorse a Special Tribunal to prosecute Russia’s crime of aggression, the legal architecture for accountability is taking shape, with one level targeting Putin and his inner circle, the other exposing the full machinery of terror behind the invasion.

If Nuremberg marked the fall of a regime, this pushes for something more urgent: justice while the bombs are still falling, because accountability cannot wait for the end of war.

Born in wartime

The Tribunal for Putin initiative began in March 2022, just weeks after Russia launched its full-scale invasion. It was founded by three of Ukraine’s most prominent human rights organizations: the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, the Center for Civil Liberties, and the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union.

“The sheer scale of atrocities was overwhelming,” says Yevhen Zakharov, Director of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group. “We had to begin collecting information immediately—before any evidence could be lost or destroyed.”

Today, more than 40 civil society organizations form the backbone of T4P. But Tribunal for Putin is not a formal tribunal—at least not yet.

“This is a global initiative,” says Zakharov. “Its role is to collect, verify, and organize evidence of crimes, international crimes that the Russians committed against our state and its citizens. So that the perpetrators—especially those who issued criminal orders—can be prosecuted for everything from bombing energy infrastructure to forced deportation of children. That’s why it’s called a tribunal”

More than 100,000 incidents have already been documented. Of those, over 5,000 have progressed into criminal cases. T4P maintains two databases: one open to its network of documenters, the other a confidential archive for legal professionals. The latter, managed by the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, includes court-ready files and protected witness accounts.

We dream of becoming unnecessary. All human rights defenders dream of the day they can be dismissed.

Oleksandra Romantsova

Executive Director of the Center for Civil Liberties

How the Tribunal for Putin works

Since the Tribunal for Putin is not a single organization, but a collaborative initiative connecting independent and government-affiliated groups documenting war crimes across Ukraine, its purpose is to help organizations stay informed about one another’s projects, coordinate efforts, and reinforce each other’s work, says Dmytro Koval, co-director of the human rights group Truth Hounds.

“If something significant arises in the course of an organization’s work—even if it’s not directly tied to the initiative—others can still learn from it, replicate its success, or amplify the findings in international forums, like the Council of Europe or within civil society,” Koval says.

Each member focuses on a specific region. This division of labor allows field teams to work with deep local knowledge of the terrain, communities, and context. Some track the destruction of hospitals and cultural heritage. Others collect survivor testimonies.

The initiative also plays a strategic role. “Our messaging helps persuade international partners that continued support for Ukraine is essential—and that accountability must remain part of the agenda,” Koval adds.

He cites two recent examples: Russia’s destruction of the Kakhovka Dam and the militarization of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (NPP). Both became high-level investigations coordinated across the network.

“Kakhovka’s destruction had clear environmental consequences with no real military advantage. That allowed us to reframe it as a global issue, not just a Ukrainian one,” Koval says. “We crafted legal and political recommendations, involved environmental groups, and helped others use our findings in their communications. And they did.”

The threat of radioactive contamination in the Zaporizhzhia NPP case, he adds, underscored how fragile nuclear safety has become.

T4P documenters rely on two main sources: open-source intelligence and fieldwork. They geolocate videos, analyze satellite images, and cross-check witness accounts. Every incident becomes a legal case file—with verified metadata and source tracking—that can be submitted to courts or prosecutors.

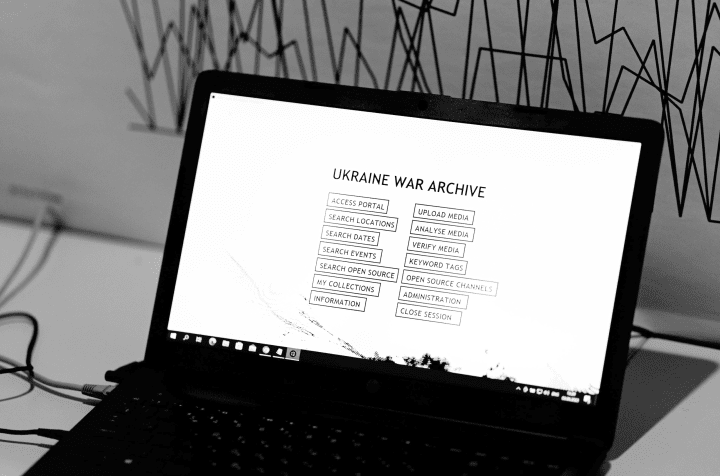

Ukraine War Archive

Behind every war crimes report and ICC submission lies an invisible but essential backbone: the data infrastructure. That’s where the Ukraine War Archive comes in.

“We consider the war in Ukraine to be the most documented war in human history,” says Maksym Demydenko, co-founder and Executive Director of the archive. “Yet much of the data remains fragmented.”

The Archive, built by Ukrainian digital archivists, unifies that evidence into a single, secure repository. It stores more than 280 terabytes of data, including 36,000 documented events manually recorded by the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group and other contributors to the T4P initiative, along with 7,200 interviews and 26 million files from over 150 sources.

The system ingests new material daily—satellite imagery, forensic reports, social media, witness accounts—but the Archive’s foundation lies in a different kind of data: unique and highly vulnerable records provided by partner organizations. These exclusive testimonies form the backbone of the Archive’s work.

And the Archive’s access is tightly controlled. Only verified and authorized partners can interact with its contents.

“We reconcile data across platforms,” says Demydenko. “If a partner is researching Russian locations, we can scan all transcribed interviews and open-source content to find relevant matches.”

Each file is assigned a unique digital fingerprint, or hash code, to guarantee authenticity—ensuring that it cannot be altered without detection.

“It ensures we can prove decades from now that not a single pixel has changed,” Demydenko says.

But the archive isn’t only about legal evidence.

“It’s not just about war crimes,” Demydenko says. “It’s about what it meant to be Ukrainian during this war: how people lived, taught their children, made art, kept their language alive.”

The legal architecture of accountability

For T4P, documentation is just the beginning. The end goal is prosecution.

Since 2022, the initiative has submitted nine communications to the International Criminal Court, citing offenses under the Rome Statute: war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide—and eventually, the crime of aggression.

“The sooner this is done, the better,” Zakharov says. “Because evidence fades. Witnesses pass away.”

National prosecutors in Ukraine handle cases against direct perpetrators—those who killed, raped, abducted, or shelled civilians. Many trials have been launched, but most are conducted in absentia because the accused remain outside Ukraine’s reach.

The ICC, meanwhile, targets top-level officials. In March 2023, it issued two arrest warrants: one for the Russian leader, Vladimir Putin, and another for his Commissioner for Children’s Rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, for the forced deportation of Ukrainian children to Russia.

Still, the ICC cannot prosecute the crime of aggression unless both countries involved have ratified the Rome Statute. Ukraine has. Russia hasn’t—and won’t. That legal gap is exactly why Ukraine and its allies are pushing for a Special Tribunal.

The tribunal, focused specifically on the crime of aggression, is expected to be hosted in The Hague under the framework of the Council of Europe. Signing is set for May 9 in Kyiv—Europe Day.

“All the legal work done up to this point by legal advisers from 40 countries—resulting in a package of documents—will now receive political backing,” said Ukraine’s Deputy Head of the President’s Office Iryna Mudra, adding that the Special Tribunal could become operational in 2026. “This year, we are finalizing the legal framework and beginning to set up the tribunal: recruiting judges, establishing the secretariat, and implementing work rules and procedures.”

Once signed, the deal will go to the Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly, where a two-thirds majority is needed. Approval is expected given widespread support, and no single country can veto the process. Democracies such as Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan are also expected to join.

But some organizations cannot wait.

“When crimes are this serious, they’re not just Ukraine’s problem, they’re humanity’s problem,” says Koval. “We use the principle of universal jurisdiction to open cases wherever possible, even outside Ukraine.”

Investigations are already underway in Switzerland and Germany, with several more pending in jurisdictions Koval cannot yet disclose.

“Universal jurisdiction cases take years, and they depend heavily on whether the accused can be apprehended,” he says. “But history shows it’s possible.”

He cites the Rwandan genocide and wars in Syria and Liberia—contexts where individuals implicated in war crimes later surfaced in Europe. Some were prosecuted years later, after fleeing violence in their home countries.

“When large population movements occur, you can reasonably expect that some perpetrators will be among them,” Koval says. “That means some of these cases will eventually lead to arrests—and justice.”

What justice means for survivors

For the Ukrainian civilians who’ve endured occupation, torture, forced displacement, or the loss of loved ones, accountability isn’t a legal abstraction—it’s personal. Thousands of testimonies have been recorded by T4P member organizations. Each one carries legal weight, but also emotional cost.

“The first challenge is documenting sexual violence,” Zakharov says. “People are afraid. They’re ashamed to speak. As of April 1, only 349 such crimes had been officially registered. But the real number is far higher.”

Over a quarter of those survivors were identified through outreach by Zakharov’s team—but not all were ready to speak to law enforcement.

Russia, meanwhile, hides the scale of its abuses. “Russia conceals where prisoners are held—especially civilians,” Zakharov says.

Nearly 63,000 people are officially listed as missing by Ukraine’s Interior Ministry, both civilians and soldiers. Tens of thousands more are confirmed to be held in over 115 Russian detention sites. Fewer than 2,000 civilian detainees have known locations.

“Russia refuses to say where they are,” says Zakharov. “What are we supposed to think? Were they killed? What happened to them? How can a state imprison people and not even say where they are? Imagine what that does to their families.”

Many are held without trial, without charges: for speaking Ukrainian, refusing to sing the Russian anthem, or take a Russian passport, resisting indoctrination.

“These are political prisoners,” Zakharov says. “And torture is widespread, brutal. It happens everywhere. No one is spared—not women, not children, not the elderly.”

-b6013e0451ca4c734e6776477f8efb15.png)

The ICC focuses on the top. National courts go after those on the ground. But T4P also holds records of the shadow actors in between: the commanders, officials, and bureaucrats who made the system of occupation and repression work. They sign the transfer orders, run the prisons, or look away from brutality. Even propagandists may be held accountable, Zakharov says, for inciting genocide and legitimizing crimes.

“What we have is just the tip of the iceberg. We’ve already documented more than 5,000 such cases.”

All evidence is secured and meets international confidentiality standards. Upon request, it can be submitted to the courts.

“Russia’s recent attack on Kryvyi Rih, for example, shows Russia’s typical strategy of denying any civilian casualties,” says Koval. “Denying that a civilian target was attacked, or—even if we were to assume for a moment that there was some military objective involved—the sheer disproportionality of the attack is staggering. The harm inflicted on civilians is staggering.”

Therefore, the Tribunal for Putin’s effort is not unlike a historical precedent.

“Nuremberg was the first special tribunal,” says Zakharov. “It created the legal frameworks we rely on today—the Rome Statute, the Genocide Convention. Nuremberg showed that natural law can be higher than positive law.”

“When Ukraine wins,” he adds, “accountability will follow. Just as it did in Germany, after the regime fell.”

-050b2b5554ed561c87f909a001f905b9.png)

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)