- Category

- War in Ukraine

“It’s a Protocol to Destroy Them”: War Crimes Investigator Father Desbois Details Russian Torture of Ukrainians

French Catholic priest Father Desbois has spent decades uncovering Holocaust crimes across Eastern Europe. Now, he and his team are documenting Russian war crimes in Ukraine’s liberated territories—gathering evidence and testimonies in the hope of bringing perpetrators to justice. UNITED24 Media talked to them for a deep dive into the Kremlin’s genocidal playbook in Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine.

Only a few days before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Father Patrick Desbois was in Jerusalem with Ukrainian officials as a scientific advisor for Kyiv’s Babyn Yar Center.

The news from Ukraine’s border was alarming. “I told the Ukrainian delegation: Leave now, take the first flight to Kyiv—you won’t get another,” he recalled saying to them.

His best friend, Ruslan, turned to him and said, “Will you come to visit our mass graves?”

Father Desbois and his team had spent decades documenting war crimes committed by the Nazis during the Holocaust in Eastern Europe with the Yahad-In Unum organization. Now, he would have to return to Ukraine, this time to document yet another genocide unfolding in real time.

Documenting torture

His team started documenting war crimes in March 2022.

As of August 2023, Yevhen Tereshchenko, a prosecutor with the war crimes unit for the Kherson region, estimated that 4,000 to 5,000 civilians were detained between February and November 2022, but the actual number may be much higher.

As of April 2025, Ukrainian authorities have documented over 183,000 alleged war crimes committed by Russian forces since the full-scale invasion began in February 2022, according to President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

“We collected the testimonies of 70 torture cases, but we have many more war crimes-related cases,” Father Desbois told UNITED24 Media.

The team has interviewed approximately 300 people so far, according to Andrej Umansky, a lawyer in charge of building cases for the International Court of Justice.

Torture chambers

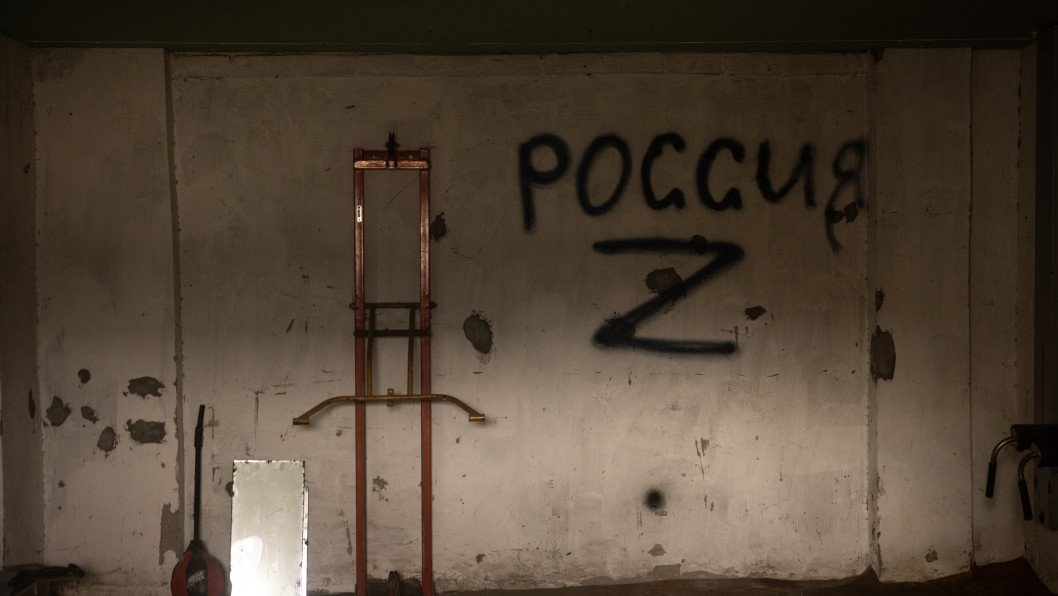

It’s in Kherson, just after the city’s liberation in November 2022, that Father Desbois entered his first Russian torture chambers.

The city was reeling after months of ordeals under the Russian yoke, an occupation synonymous with systemic abduction and torture.

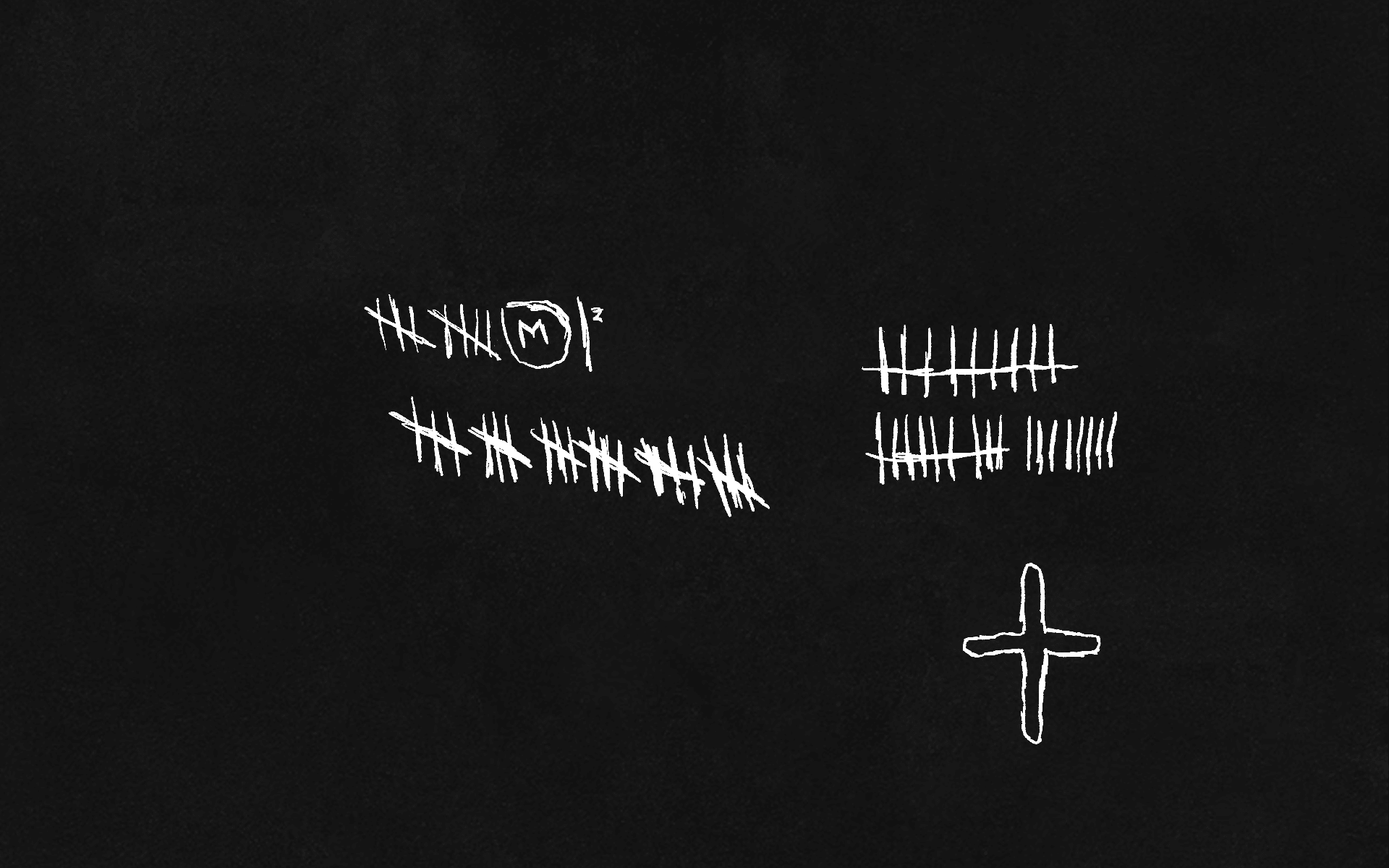

Father Desbois recalled Kherson’s sordid prisons’ cells without chairs or tables, where up to seven detainees or more could be crammed in two by three-meter rooms.

“The detainees were wrecked. When the doors opened, they were forced to salute (Vladimir) Putin. They couldn’t even stand; torture was rampant.”

Father Patrick Desbois

Priest, war crime investigator

One of the survivors told him that as the Russians ran out of space in the torture rooms, they tortured him in the corridor. However, some larger cells had metal furniture, where “only three prisoners” were held.

The gathered testimonies quickly revealed that the Russians brought in some psychologists during interrogations to search for their breaking points and force the local community’s most influential figures, such as teachers or civil servants, to swear allegiance to the Kremlin on video.

The Kremlin also sent a vast number of FSB agents in Kherson to gather and interrogate these people, a sign of a pre-planned ploy to take over occupied territories through a centralized and organized method, he said.

Two teams tortured them, one following a textbook, while using physical abuse, and another one adapting it to each detainee through psychological violence.

“One of them was deported to Crimea, where he was tortured for six months,” Father Desbois said. “The Russians told him: “We’re torturing your mother next door, work for us and we’ll stop.”

He broke. His tormentors made him sign a paper saying he was pro-Russian and filmed his forced confession to send it to the Ukrainian side to blackmail him in case he changed his mind. If he refused, he could be sent to a Russian jail for 15 years.

Meanwhile, a “well-dressed” man came up to him with a job offer he couldn’t refuse anymore.

“That was a mystery at first, when some Ukrainian official told me that when the Russians arrive somewhere, “roughly 100 people disappear,” he said. “They don’t disappear, they’re sent to Russian prisons, are tortured, or killed.”

“They torture them to make them renounce their Ukrainian identity,” Father Desbois said.

Rape as a weapon of war

One of Kherson’s Russian jailers was from Chechnya. His job was to rape men, survivors told Father Desbois.

The torture cases’ testimonies included severe beatings, electricity shocks and rape, including of men. “One man was tortured in a makeshift torture cell, in a basement behind a house. He was attached to another prisoner; they were completely destroyed,” Father Desbois recalled.

“At the end, they told him they’d rape him, and the detainee begged: “Please, no, Jesus-Christ, I’ll kill myself if you do that.”

The soldiers ended up raping the detainee he was attached to.

Over 68% of Russian soldiers' sexual abuse in detention was committed against men, according to figures from a United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) report published in December 2024, documenting 370 cases of sexual violence since February 2022.

However, the numbers are likely much higher, as sexual abuse remains taboo.

Russian soldiers systematically raped and committed sexual violence against women of ages ranging from 19 to 83 years, often together with threats or commission of other violations, according UN official Erik Møse.

“Frequently, family members were kept in an adjacent room, thereby forced to hear the violations taking place,” Møse said.

“It’s a machine to break people, and there’s a protocol, it’s part of a system to destroy Ukraine’s identity.”

Father Patrick Desbois

Priest, war crime investigator

The difference between Russia’s war crimes and the Nazis is that the Nazis were not torturing Jewish people for them to become Nazis, he added.

“Here, the aim is not to destroy the last Ukrainian but to destroy the Ukrainian identity,” the priest said. “We see a will to annex this identity.”

Need for justice

The team must approach violent traumas delicately, Father Desbois said.

“We’ve been doing it for 20 years, we know what happened, so we never directly talk about it; it’s better to wait for the person to open up.”

In Iraq, for instance, rape survivors would never say it directly but say “Someone took my honor,” yet, in Ukraine, people tend to talk about it, especially when they witnessed sexual abuse.

The definition of war crimes extends beyond torture. Missile strikes on civilians, for instance, also count.

In some cases, Russian soldiers also regularly ambushed civilians in cars as they were following a convoy. All of a sudden, the Russians appeared out of nowhere and started shooting at everybody, killing the husband and the kid. One woman had her kid on her belly; she felt the bullet go through her child.

“One of our first witnesses was the hardest,” Father Desbois recalled. It involved a woman who hid with her son and sister in a corridor to escape a strike. But when the missile hit, the violence of the strike had beheaded her son, and her sister was in pieces.

She was the only survivor.

“She insisted on talking, gave us her name, number — we don’t have anonymous testimonies. Everyone wants their torturers brought to justice.”

Father Patrick Desbois

Priest, war crime investigator

Proving genocide

And this is where Andrej Umansky comes into play. “We borrow a bit from criminal police methods,” the organization’s lawyer said. “We really focus on the facts.”

It means asking as many questions as possible about the perpetrators: what they were like, how they spoke, tattoos, hair or eye color, but it’s no easy feat, since the victims usually had bags on their heads during torture sessions.

From the start, Umansky’s goal was to preserve information for judicial purposes and safeguard the memory of concrete facts.

“I’m also a criminal lawyer, and we say that witnesses are still, to this day, the most important part of a trial,” he said.

Like Father Desbois, Umansky was struck by the witnesses and survivors’ willingness to talk.

“What surprised me—and it’s also why we had so much success and were able to interview so many people—is that people wanted to talk. They wanted their words to be preserved so they could be used in court.”

Andrej Umansky

Lawyer

War crimes are easy to prove and prosecute, he said, since they’ve been committed en masse.

Meanwhile, crimes against humanity, which carry the same penalty as genocide under the Rome Statute (info button), are easier to prove than genocide, the lawyer explained, because the prosecution only needs to show a systematic attack on the population of a country.

In case of genocide, the prosecution must prove intent. While there’s no judicial consensus on the topic, some experts like Eugene Finkel, an associate professor of international affairs at Johns Hopkins University, believe Russia is intentionally targeting a national identity group.

Finkel notably referred to the dehumanizing rhetoric coming from Moscow, pointing to an article titled "What should Russia do with Ukraine?” published in the early days of the full-scale invasion and calling for mass extermination of Ukrainian elites and “reeducation,” the Russian way.

Concerning crimes against humanity, it is enough to “demonstrate that in Ukraine, everywhere the Russians were occupying, crimes were committed,” Umansky said, to counter the Russian narrative that those were isolated events.

Some courts, like German courts, also have “universal competence,” meaning that if the court isn’t linked to the perpetrators or the victim in a crime committed abroad, the culprit can be judged there.

Umansky, for instance, initiated legal proceedings for a Ukrainian woman who had been raped and later recognized her Russian rapist online.

The German judiciary has agreed to exercise its universal jurisdiction, and the survivor traveled from Ukraine to Germany to give her testimony. The proceeding is still ongoing, but it’s a good sign, according to Umansky.

Their investigations also target soldiers or low-ranking officers, who cannot hide behind “orders” and can be arrested anywhere in the EU if they decide to travel there, as these crimes have no statute of limitations.

“So even if, in one year, five years, or ten years, that person decides, 'Oh, I’d like to take a vacation on the French Riviera because I love France,' they will be arrested. And they won’t be able to say, “Oh, but that’s ancient history, it happened a long time ago,” Umansky said.

One caveat: justice takes time.

“Trials do take place, just not immediately, in three years, five years, ten years,” he said.

“These kinds of trials and procedures require patience. And in my view, in the end, not for all, but for some of the perpetrators—they will end up in court.”

Andrej Umansky

Lawyer

Yet, some danger lies in war fatigue, especially in public opinion, when cold statistics overshadow the personal stories of the victims, Father Desbois said.

“And it’s not good, because when someone loses his wife, he loses a loved one, not a number.”

Father Desbois' fight for justice is inextricably linked to his faith and commitment as a priest, he said.

“You know, it’s the beginning of the Bible. Cain kills Abel, and God doesn’t ask, “Why did you do it?” He says, “Where is your brother?” the priest said.

“And so, it’s very curious that God’s question is, “Where is he, where is the other? And Cain replies, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” And God says, “Your brother's blood is crying out to me from the ground!”

“And so I’ve always felt that we cannot accept, in society, the mass killing of civilians, whoever they may be, and then go on to build society as if they were never killed.”

Father Patrick Desbois

Priest, war crimes investigator

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)