- Category

- World

Russia’s “Eyes and Ears”—and Hands. How the Kremlin Recruits Europeans for Its Hybrid Warfare Against the West

“We need eyes and ears in Ukraine and Europe,” reads a message from an anonymous Telegram user. This recruiter’s mission is to scour EU citizens to photograph NATO military bases and equipment. But if they can push for more, they will.

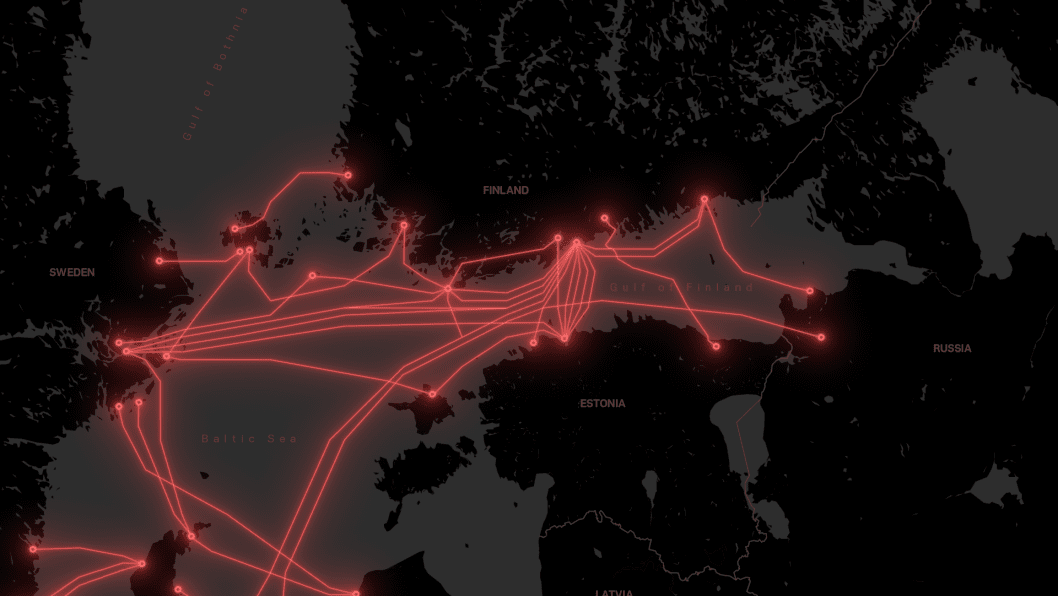

Russia’s hybrid warfare has infiltrated Europe, using sabotage, espionage, cyberattacks on government and civilian agencies, and even damaging underwater internet cables. In 2024 alone, nearly 100 of 500 suspicious incidents across Europe were linked to Moscow, with UK intelligence calling the Russian sabotage campaign “staggeringly reckless.” From graffiti defacing NATO’s Cyber Defence Center to arson at Germany’s Diehl Metal defense plant, no target is off-limits. While preparing covert bombings, arson attacks, and infrastructure damage on European soil—both directly and via proxies—Russia shows “little apparent concern about causing civilian fatalities,” said European intelligence officials.

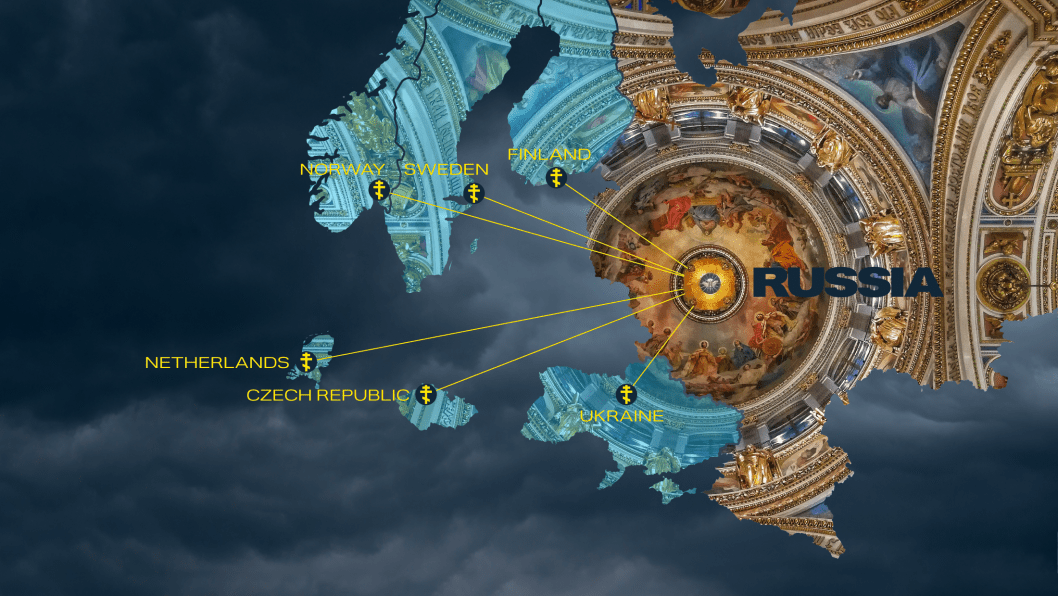

The Kremlin’s mission? Cut off support for Ukraine’s war effort, slow arms transfers, and sow fear and more divisions in the West. All while recruiting locals to do the dirty work.

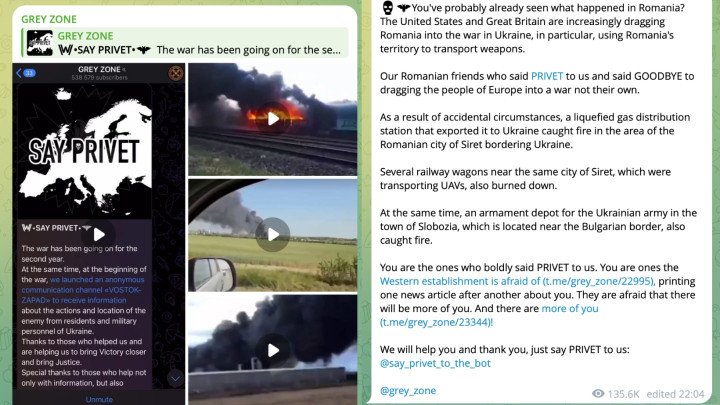

Recruitment process: Just say PRIVET

It begins with a job offer. Recruitment ads often appear in pro-Kremlin Telegram channels or private chats. They are deliberately vague.

“We pay well,” promises a recruiter behind a Telegram account, Privet Bot . “From $10,000 per mission.” Privet Bot is talking to 26-year-old Valeriy Ivanov, an Estonian citizen. But “Ivanov” is no real person—he’s a fake persona created by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and European media outlets to investigate how the recruitment works. Together, they created a social media presence and a forged ID to pose as a potential recruit.

“Ivanov” seems to be a typical target—a young man in need of extra cash. The recruiters usually focus on Russian-speaking residents of Europe, people struggling financially, and living on the fringes of society. A criminal background is a big bonus.

The questions Privet Bot asked Ivanov provide insight into a Russian recruiter’s main points of interest about a would-be saboteur: Whether he has military experience and knows how to use weapons, whether he is self-motivated and willing to act independently, and whether he is prepared to undertake dangerous work.

Once someone expresses interest, the vetting begins. Recruits are often asked for IDs to “prove reliability.” Questions about military experience, weapons knowledge, the ability to operate independently, or readiness to take on dangerous tasks might follow—revealing exactly what Russian recruiters prioritize in a would-be saboteur.

While large sums are promised, the tasks rarely justify the compensation. For instance, €400 might be offered for something as simple as spray-painting graffiti. Payments are typically made through untraceable methods like cryptocurrency or digital banking apps, with partial payments often made upfront to build trust.

From a photo snap to killing for cash

The job often starts small: gathering intelligence. A Novaya Gazeta Europe investigation reveals that recruits are tasked with snapping photos of NATO bases, collecting detailed maps and guides, and even buying anonymous SIM cards to send to Russia. Recruiters prioritize intel on military equipment movements, storage facilities, and locations training Ukrainian specialists. Areas near the Belarusian border are of particular interest— NATO forces may be concentrated there. Questions about the purpose of this data or its potential use for sabotage are brushed aside with responses like, “Let’s start small—information.”

But “small” may quickly escalate. Tasks shift to sabotage—vandalism, arson, bombing, and cryptocurrency laundering. Instructions arrive as detailed text messages or images, specifying locations, tools needed, and exact steps to complete the task. Operatives are provided with necessary resources—spray paint, cameras, or even Molotov cocktail ingredients—or the cash to buy them.

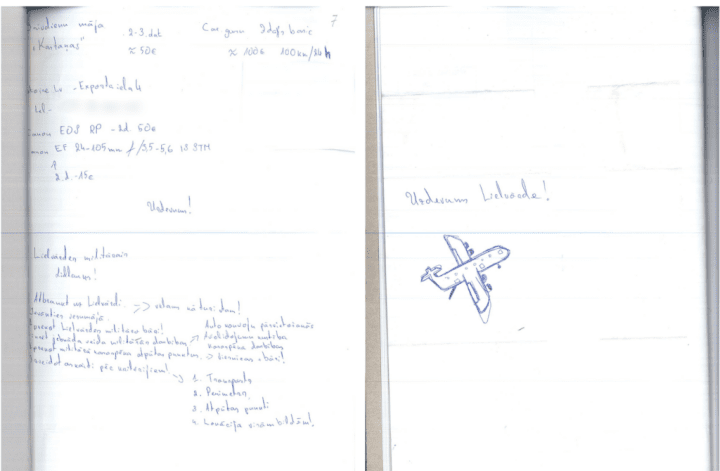

Take the case of 21-year-old Sergejs Hodonovič from Latvia, reported by the journalists from Re:Baltica. First tasked with photographing an airbase, Sergejs and his partner spray-painted “Killnet hacked you” outside the NATO Cyber Defence Center in Tallinn, coinciding with cyberattacks on Estonian state services. Investigators linked Hodonovič to Russia’s GRU after uncovering photos of military targets and espionage instructions on his phone.

Higher-paying jobs come with bloodier price tags. After tasking “Ivanov” with practicing throwing a Molotov Cocktail, the recruiter behind Privet Bot upped the stakes: “Have you ever killed? Committed any crimes?”

When “Ivanov” tried to steer the conversation to lower-stakes tasks, like torching a car, the recruiter dismissed it. “We’re interested in military objects and military equipment,” the recruiter said. “A civilian car? That’s not even a mission.” Preferred targets included tanks, armored vehicles, and radar stations—especially NATO’s, though any radar would do, depending on the price. When asked how much killing pays, the recruiter responded: “$10k per head.”

Who’s behind the recruitment?

Operating under aliases and disposable accounts, these recruiters remain anonymous. The user behind Privet Bot is unknown and has not been linked to any specific sabotage incidents, but officials from four European security agencies confirm that its tactics resemble Kremlin-linked sabotage recruitment operations. Latvia’s Security Service added that Telegram is a known tool for Russian intelligence.

Some accounts tied to these recruitment efforts have been identified. Ksenia Temnik, an official within the Russian puppet administration in Crimea’s military wing has been linked to an account KS, which distributes recruitment posts across Telegram groups, according to Novaya Gazeta Europe journalists. A Russian passport holder since 2014, Temnik allegedly manages several pro-Kremlin groups on Telegram. Meanwhile, the bot operator contacted by the journalists hinted that their handlers are linked to Russian Airborne Forces (VDV).

Behind the recruitment of Hodonovič is a network of operatives. A middleman known as Green (Gļeb) facilitated low-level tasks—graffiti, espionage, and arson—while also running a money-laundering operation to help “mules” withdraw cash and convert it into cryptocurrency. At a higher level, a user nicknamed MOT (Martins Griķis) oversaw payments, vetted recruits, and coordinated operations with a Russian handler named Alexander. Over two years, Griķis reportedly pocketed €10,000 in commissions, while Alexander kept everything under wraps, communicating exclusively through Telegram, frequently changing usernames and phone numbers.

The system thrives on compartmentalization. Operatives rarely interact directly, relying instead on middlemen to relay instructions. Handlers exploit Telegram’s encrypted messaging, auto-delete features, and pseudonyms to maintain their anonymity, ensuring the Kremlin’s fingerprints are nearly impossible to trace.

The known cases

“There is a psychological impact [on the West], but also a material one [for Ukraine],” said Jenny Mathers, a specialist in Russian intelligence services at Aberystwyth University in Wales, referring to the fact that most of the targets are either ammunition depots intended for the Ukrainian army or infrastructures in the supply and delivery chain, such as rail networks or airports.

Over the past year, European countries have exposed several possible Russian intelligence-backed sabotage operations:

Estonia: Suspects detained for vandalizing monuments and wreaking officials’ property in February.

Latvia: Two men on trial for attempting to torch the Occupation Museum with Molotov cocktails in February. Same month, Russian-Estonian citizen arrested over the vandalism of memorial.

Lithuania: An IKEA store caught fire under suspicious circumstances in May.

Poland: A Russian spy group was uncovered in 2023, accused of planning to sabotage a railway delivering aid to Ukraine. A man arrested after trying to collect information about security at Rzeszow airport in April. Then, fires in Warsaw’s biggest shopping center in May suspected as arson attacks.

Germany: Two Russian-German nationals were arrested in April for plotting attacks on US military sites. In May, a fire at the Diehl Metal Defense Factory that manufactures IRIS-T air defense systems used by Ukraine was linked to Russian saboteurs.

United Kingdom: Two British men were charged with assisting Russian intelligence after an arson attack on a Ukraine-linked warehouse in London in March. Next month, an explosion rocked British defense contractor BAE Systems’ factory in Wales. The factory also manufactures weapons for Ukraine.

US-bound planes: Devices intended for sabotage were intercepted in Lithuania, Poland, and Germany. Police suspect these were test runs for attacks on transatlantic flights, bound for the United States and Canada.

Additionaly, US artillery shell factory in Scranton, Pennsylvania, that ships some of its products to Ukraine went up in flames in April.

The reckless and the desperate

Many of those involved in sabotage have criminal records, a fact that MI6 Chief Richard Moore says exposes Moscow’s growing desperation: “Criminals do stuff for cash. They are not reliable, they are not particularly professional, and therefore, usually, we are able to roll them up pretty effectively.”

Hodonovič, whose sloppy work led to his capture, is a prime example. Since the Telegram chat automatically deletes messages, he wrote sabotage instructions on a piece of paper—and then lost it. The paper was later found by a woman in her driveway. Similarly, the perpetrators of the Latvian Occupation Museum arson, with previous drug offenses, left behind masks and gloves that police traced back to them.

Yet, despite the blunders, the attacks continue. Even if Russia doesn’t aim high when it comes to sabotage, going for “so-called low-level agents,” attractive for their accessibility and expendability, according to a source from a German security agency, the long chains of middlemen make it difficult to attribute the recruitment to specific actors. “All three Russian secret services would be capable of doing this.”

Research by Leiden University’s Bewaken en Beveiligen project, led by Professor Bart Schuurman, underscores Europe’s unpreparedness. “What we are witnessing is a clear escalation of Russian tactics. These are no longer limited to cyberattacks or propaganda but now include actions with direct consequences for physical infrastructure and civilian safety.”

Marta Tuul, a member of Estonia’s KAPO intelligence agency, believes the goal of these operations is clear: to “incite fear, discontent, and confusion within society.” The Kremlin uses chaos to further its geopolitical agenda while avoiding direct involvement. Latvian Interior Minister Rihards Kozlovskis calls it a prime example of Russia’s hybrid warfare, stating that a successful museum attack would have “caused a significant public outcry and achieved the intended goal.”

Schuurman warns, “Europe must invest in resilience and develop a joint strategy to effectively combat sabotage and hybrid warfare,” or risk further destabilization.

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)

-661026077d315e894438b00c805411f4.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)