- Category

- Perspectives

Do World Institutions Still Work and Global Leaders Still Lead? Here’s What One of Ukraine’s Most Prominent Diplomats Thinks

-7a13108e007da669337bd6ec35c24256.jpg)

From Ukraine’s first independence days to today’s global diplomacy, one of Ukraine’s most prominent diplomats, Volodymyr Yelchenko, offers his view on the realities shaping international institutions and leadership in this exclusive interview with UNITED24 Media.

Volodymyr Yelchenko has been at the heart of Ukraine’s diplomatic evolution. From witnessing the birth of Ukraine’s diplomacy post-independence, including chairing the electoral commission in New York during the independence referendum, to confronting Moscow’s aggression as Ukraine’s Ambassador to Russia in 2014, Yelchenko has seen it all. Having served as Ukraine's Ambassador to the US, UN, OSCE, Austria, and more, he was also present when Ukraine's new flag replaced the Soviet one at UN headquarters, recalling how the Ukrainian diaspora worked tirelessly overnight in 1991 to make it happen:

“Turned out, we needed not one, but three. One to fly outside with the flags of all UN member countries, another as a reserve in case something happened, and the third as a protocol sample. I had to rush to the local Ukrainian community to ask for more, but time was running out. The next day, President Leonid Kravchuk was set to visit the UN, and everyone wanted to ensure everything was ready. That moment marked the beginning of independent Ukraine’s history as part of the UN.”

The first year of Ukrainian independence was far from easy.

“Russia essentially took over the USSR’s UN membership, disregarding established rules, procedures, and the UN Charter. Since then, Russia has been the only member that bypassed the usual process all other countries followed. At the time, we were powerless to stop it. This issue remains a point of contention, and today, our diplomats are working to challenge Russia’s legitimacy and revoke its status. It’s politically difficult, but suspending their credentials is possible – and this is what our diplomats are currently working on.”

How did Ukraine begin building its diplomatic network after independence?

“That was a complex period in our history. Countries began recognizing us at a rapid pace – Hungary, Poland, the Baltic states, Canada, and the United States. We had to build a diplomatic network. At the time, Ukraine only had a mission in New York, with small offices of one or two people in Geneva, Paris, and Vienna. Our first embassy was in Poland. Imagine – in early 1992, Ukraine’s entire foreign ministry staff was about 45-50 people. We had to find ambassadors, embassy staff, and the necessary funds to rent or purchase premises, vehicles, and communication systems.

We were lucky that Ukraine, like Belarus, had a small established Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a few dozen staff. This provided a foundation that other post-Soviet states didn’t have. Our international relations faculty at Kyiv University and its institute helped by supplying many graduates for diplomatic service. We had to make numerous laws.

An important law I was directly involved in was the law on Ukraine’s participation in peacekeeping operations. By the mid-1990s, our troops were part of missions in Africa. Plus to that, Kosovo, Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia, and even Lebanon, Colombia, and Haiti. This required a solid legal framework covering military service procedures and compensation. That period of diplomatic expansion was crucial – laying the groundwork for what we have today.

Now, the primary challenge is war, but those early years were also tough. My colleagues and I are proud to have been part of the birth of modern Ukrainian diplomacy.”

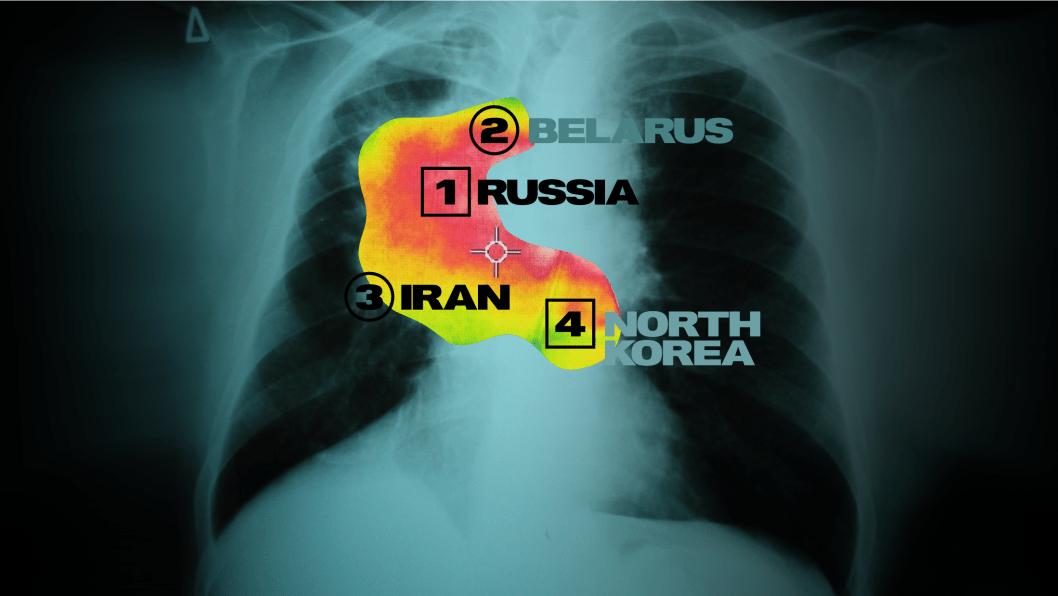

The war in Ukraine seems to have united Europe in ways not seen in years. On the other hand, Russia and its “axis of evil” are fueling fresh global tensions. Do you believe the world is slipping back into Cold War-style divisions, and can diplomacy still bridge these divides?

“The actions of Russia and its allies on this ‘axis of evil’ leave little room for optimism. The key difference today, compared to the Cold War, is that international law has been almost completely discarded. This system, which underpinned global relations for nearly two centuries, is now broken. The international law we see now was born in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, following numerous wars across Europe.

This system solidified after World War II, with the creation of the United Nations. From that point on, the system largely prevented major global wars. Cracks began to appear around the mid-1990s: the Yugoslav Wars, the Syrian War, the Russian aggression in Georgia, and, eventually, in Ukraine. This has shattered the old system.

Some call the Cold War the World War III and argue that we are now in the Fourth. This war isn’t only fought on battlefields; it’s hybrid. Ukraine is at the epicenter, but far more countries are involved than you might think. A handful of countries back Russia, even during UN votes. They're not our allies. Then there are dozens of neutral nations. Some want to avoid confrontation with Russia, while others feel detached from the war. This is part of the problem. The system has been dismantled, and it leaves us in a precarious position.”

Do institutions like the UN still hold real influence in today’s world? And is it possible to reform them to meet modern challenges?

“When I am asked if we can reform the UN like after the League of Nations was dissolved post-WWII, I say it's only possible with a real World War III. The world’s changed so much that only a global catastrophe could show the current international system is not working. At the core of the problem is Russia, with its veto power in the UN Security Council, blocking everything—this isn’t just about Ukraine, look at Syria. Something has to change.

I hope one of the lessons from this war, after our victory, is the creation of a new international system. Essentially, it’s already forming. A union of democratic countries. Some call Ramstein its backbone, around which a future international system could be built. Over time, more countries will join.

Yet, there’s still a question of the Global South. Many countries there either misunderstand the war or simply don’t care. They feel it doesn’t affect them directly, which is why they do not assume a more active position in Ukraine’s support. However, I believe that, in time, they will come to understand the stakes. Until then, we need to continue holding the flag high.

Everyone is anxiously awaiting when Trump assumes the presidency in the United States. His statements have been contradictory, and it’s difficult to predict his policies. Still, I hope that justice and fairness will guide him, which could lead to Russia’s defeat and the formation of a new international order.”

Is there still a significant step the UN could take right now to counter Russia’s aggression?

“The UN should bring the issue to a vote and pass a resolution that questions Russia’s credentials. While this wouldn’t physically expel Russia, it would be a serious moral and emotional blow to its diplomacy. This might prompt reconsideration among countries in the Global South, who currently pay little attention to the situation.

This step wouldn’t bring about a dramatic shift, but it would mark the beginning of a new international order – a process many experts talk about, though few can fully envision what it might look like.

Unfortunately, unlike in 1945 after WWII—or even during the Cold War—there are no leaders today, in the West or globally, of the same caliber as back then. The kind who, as we say now, can ‘see over the horizon’—who can anticipate what might or might not happen in ten, twenty, fifty years if certain actions aren’t taken today. I’m talking about leaders like Churchill, Reagan, Thatcher, or Mandela. We don’t have such people now. That’s why we see hesitation in supporting Ukraine—fear of Russia or nuclear weapons. Western politicians are more focused on their next election and on how to be liked by the people.

Look at France, Germany—even the UK, though Britain has been more assertive on the global stage. There just aren’t enough bold leaders. I mention Reagan for a reason—his efforts helped break the Soviet Union. It didn’t happen to Russia in 1991-92, but this empire could have been dismantled further. If it had been, we wouldn’t be dealing with today’s problems—not just in Ukraine, but across Africa, Latin America, and beyond. This ‘axis of evil,’ led by Russia, exists because the West let it happen. Gas deals, and ignoring Russian aggression—these choices brought us to this crisis.

We need a leader, or a group of leaders, who finally get it—if decisive action isn’t taken against Russia now, it could lead to a full-scale World War III. Since everyone knows that war would be nuclear, the consequences for our planet could be catastrophic.”

Speaking of leaders – When UN Secretary-General António Guterres visited Russia, was it a genuine act of diplomacy or a move that inadvertently legitimized a dictator? Do such diplomatic efforts hold any real value in the face of aggression?

“I view Guterres in the same category as leaders like Viktor Orbán or Robert Fico—people who don’t have the right to be leading serious states. Guterres is one of the weakest. Perhaps corruption, fear of Russia, or simple hesitation holds back stronger responses. Guterres, in particular, is nearing the end of his second term and doesn’t need to secure re-election, so I don’t understand his reluctance to take a firmer stance.

The same applies to other leaders like Lukashenko, who clearly fits into the ‘axis of evil.’ Everyone recognizes the problem, yet no one takes decisive action. Economic sanctions, while important, are often too lenient or full of loopholes that allow Russia and its allies to circumvent them. Take Iran, for example – it has existed under sanctions for about 40 years. Russia, too, has adapted to sanctions remarkably well. Why? Because there are too many exemptions and workarounds.

All this talk about the umpteenth sanctions package – it’s just window dressing. It doesn’t really get results. Honestly, I don’t think any economic or financial sanctions can truly rein in a country that refuses to comply with the existing world order.”

Do you think international courts hold real sway in modern geopolitics, especially considering cases like Mongolia's failure to arrest Putin despite the ICC's ruling?

“No, they don’t. This ties into what I mentioned earlier – the international legal system is effectively broken. When the overall system lacks credibility, how can we expect individual institutions to have any authority?

Like with Mongolia, why not sanction it if it is established that the country has violated its obligations? But nothing is done about it. If an aggressor state ignores the very rules and agreements it once signed and sees that there’s no accountability, it will keep up its actions. This is what has led to the chaos we’re now seeing across the globe.”

Reflecting on your time as Ukraine’s Ambassador to Russia in 2013-2014, could anything have been done to prevent today’s full-scale war?

“There was very little action. There were strong words – non-recognition of Crimea’s attempted annexation, condemnation of sham elections in Donbas – but real, impactful measures were scarce. Yes, sanctions were imposed, but they didn’t significantly affect Russia’s economy. Even today’s stronger sanctions haven’t completely crippled Russia.

In 2014, more decisive actions were needed. The West could have pushed harder for Ukraine’s NATO membership or formed a coalition to deter Russian aggression. But back then, Ukraine wasn’t ready for NATO – far less so than today. And yet, no one even nudged us toward membership.

A pro-Ukrainian coalition could have been created, something like what was done with Ramstein that came much much later. But why couldn’t this have been done back then? We could have stopped Russia then.

When I left Moscow in March 2014, I told my colleagues at the embassy that we were witnessing the beginning of a large war. Russia’s aggressive stance, coupled with the West’s hesitation, made it clear that this would escalate. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened in February 2022.

No one acted preemptively back then. Everyone – at least in the West – thought that if they gave Russia a little something, things with Ukraine would stop there. They believed it wouldn’t affect them. But now, things are starting to shift. The right decisions and actions that could have changed the situation weren’t made in time. And that’s exactly why we are where we are today.

The same thing as in 2014 could happen again. They'll push us into talks with Russia, maybe even a ceasefire. Then, it'll drag on with endless debates over who owes what, whether to return territories and what to do with Crimea and Donbas. This could go on for years, maybe decades, and eventually lead to another conflict explosion.

We might hear talks of Western troops in Ukraine in a few years, but again nothing will come of it. Some would say, again, ‘What about Russia’s consent?’ But Russia will never consent. Isn’t that clear by now? What are we waiting for then? Until the Russians take all of Left-bank Ukraine? Only then will the West send in its troops? We need to act, not just hold endless discussions on matters that affect not only our survival as Ukrainians but the survival of Europe because Putin will never stop until he achieves his goals or until someone truly stops him.”

-588ae190d45987800620301cc34e2cf8.png)

-886b3bf9b784dd9e80ce2881d3289ad8.png)

-c42261175cd1ec4a358bec039722d44f.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)