- Category

- Anti-Fake

How the Soviet Passports Kept Millions in Slave-Like Conditions Until the Computer Age

When was slavery abolished in your country? The Soviet Union’s myth was one of promised equality and progress. Yet millions lived as state-bound peasants—for them, serfdom was reintroduced and didn’t truly end until the 1970s.

After the Soviet Union was established, the government eventually introduced a single form of identification in 1932. Before that, the ID only contained basic personal information, and a photo could be added at the owner’s discretion. When it finally became mandatory for city residents and workers, it still excluded most rural citizens—for over 40 years.

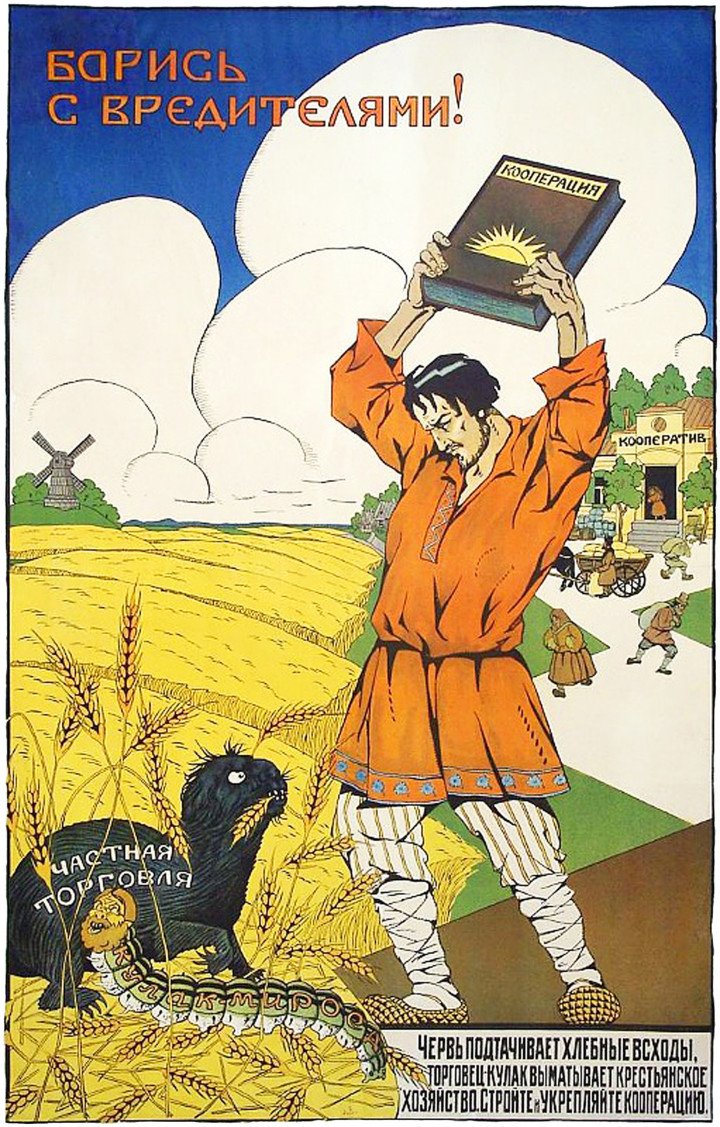

Forced collectivization

In the early years of Soviet history, passports were considered a relic of the past. The Small Soviet Encyclopedia of 1930 stated:

“The passport system was one of the most important tools of police control and tax policy in the so-called police state… Soviet law does not recognize a passport system.”

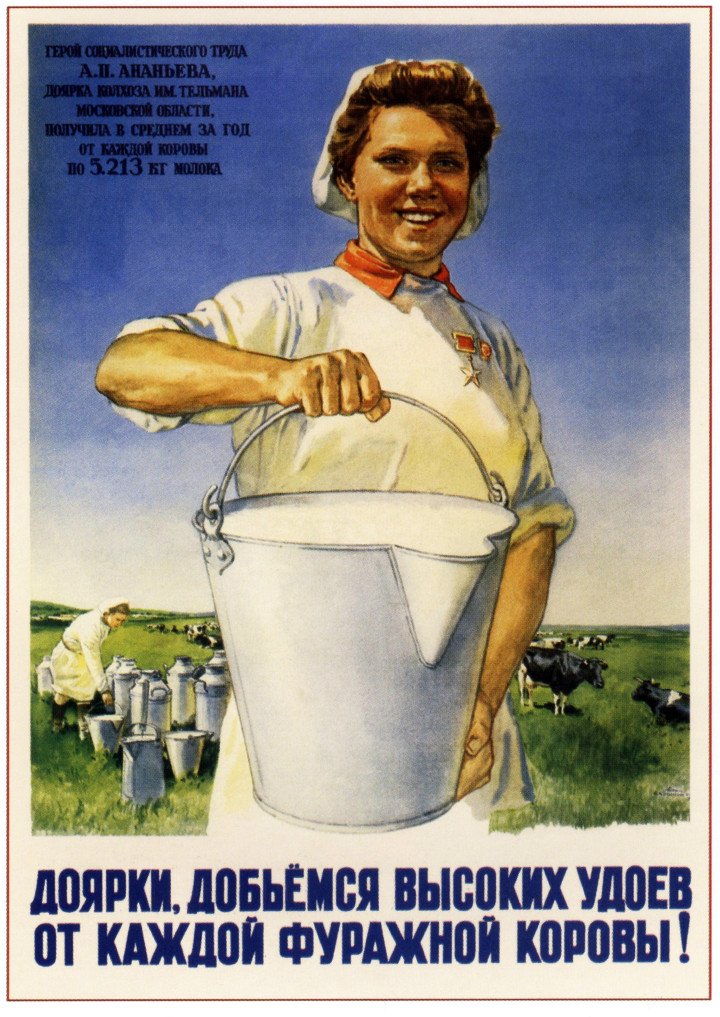

However, things were already beginning to change. The USSR launched forced collectivization—the creation of large collective farms based on peasant households. In practice, the goal was to turn all rural and urban labor into workers for state enterprises. This gave the communists total economic control over the population.

One consequence of collectivization in the early 1930s was famine, which, due to the policies of the Soviet leadership, was particularly devastating in Ukraine. There it became known as the Holodomor. As a result of deliberate restrictions, terror, and the confiscation of food by the authorities, an estimated 3 to 7 million Ukrainians died. Today, dozens of countries — including the United Kingdom, Italy, Canada, Germany, the United States, France, Brazil, and Australia—recognize the Holodomor as an act of genocide.

As peasants fled forced collectivization and famine, the Soviet government sought to regain control. In 1932, it abandoned the principles of its own encyclopedia and introduced an internal passport system. But this system wasn’t meant for everyone—and certainly not for the convenience of citizens.

“The same as under serfdom”

The passport system did not apply to most peasants. At age 16, they were “voluntarily” enrolled in collective farms (kolkhozes). They could not travel farther than their district center without written permission from the local authorities. Unauthorized travel was punished by a fine; repeated violations could result in up to three years in prison.

Passports became a tool of control for peasants. In cities, they became a means of combating “unreliables.” Those denied passports were automatically expelled—banned from living within 100 kilometers of major cities. In just the first months of 1933, Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, and other Ukrainian cities lost several hundred thousand residents.

Writer and journalist Olga Bergholz kept a diary during those years. In it, she mentioned a certain Zemskova—likely a collective farm chairwoman—and recalled how she scolded a friend’s son:

“Zemskova said that Kolya is a terrible boy. The teachers even cried because of him. They were studying serfdom in class, then talking about how free life is now. He said — it’s still the same as under serfdom. Everything goes to the collective farm, from there to the state, and we get the scraps.”

The only real difference between collective farmers and slaves was that a peasant could no longer be sold or traded for a horse or a pedigree dog. In every other respect — backbreaking labor for an all-powerful state and a total lack of rights or freedom of movement — little had changed.

When oppression became inefficient

This system of control lasted for decades. Peasants had no documents and no right to move freely. Migration to cities was only possible with permission from local authorities. Even in 1967, 37% of the USSR’s population—some 58 million rural adults—still lived without passports.

It was also a form of colonization. Russians were resettled into cities, while even native Ukrainians were pressured to switch to Russian. The Ukrainian language was increasingly stigmatized as “rural” and backward. Those who spoke it and managed to move to a big city often had to adopt Russian to blend in.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Soviet leadership realized that the ruthless exploitation of collective farm “serfs” was economically inefficient. The countryside no longer needed as many workers as the rapidly growing industries in the cities. Change was inevitable—not out of humanitarian concern, but for economic gain.

In 1974, while NASA’s Pioneer 11 became the first spacecraft to fly past Jupiter, the Altair 8800 ushered in the personal computer revolution, and scientists Georges Köhler and César Milstein developed monoclonal antibody technology—the USSR finally decided to relax its system of oppression.

1974: Passports for peasants

That year, the Council of Ministers approved the Regulations on Passports in the USSR. The key innovation: all citizens, including rural residents, would now receive passports at age 16. For the first time in nearly half a century, collective farmers gained limited freedom of movement and the right to choose their place of residence.

Still, they could not take a job in a city without documentation from their collective farm administration. A former peasant could move to a city only by accepting work in industries with harsh or hazardous conditions—jobs city dwellers generally avoided.

The new passports began to be issued in 1976, and by the end of 1981, around 50 million peasants had received them.

With those very passports, they witnessed the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991—a state where elements of serfdom survived until the final quarter of the 20th century.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)