- Category

- Culture

Three Ukrainian Films Gain Spotlight on 2025 European Film Awards Shortlist

At the 2025 European Film Awards, three shortlisted Ukrainian films confront war and belonging, marking Ukraine’s expanding presence on the European cultural stage.

Ukraine on Europe’s cultural map

Three Ukrainian films have been shortlisted for the 2025 European Film Awards: Militantropos, Songs of a Slow Burning Earth, and Daddy’s Little Scratch. Each one, in its own language of silence, confrontation, and care, places Ukraine at the center of Europe’s moral and artistic conversation.

The announcement came from the Ukrainian Film Academy earlier this week. For a country that has long been defending its physical borders, its cultural ones are now expanding, not only through the rhetoric of resilience but also through cinema. These works do not plead for recognition, do not use voice-over, and steer remarkably clear of “telling you what to think.”

Founded in 1989 by a group of European filmmakers led by Ingmar Bergman, the European Film Academy has positioned itself as a collective conscience of the continent’s cinema. Its members (now numbering more than 5,000) have sought to define what “European” means beyond language and geography. This year, Ukraine’s presence within that definition is no longer peripheral.

The European Film Academy, under the presidency of Juliette Binoche and the direction of Matthijs Wouter Knol, continues to emphasize unity through diversity—a phrase often attributed to EU sentiment.

The human as battlefield

Militantropos, directed by Alina Gorlova, Simon Mozgovyi and Yelizaveta Smit, the film takes its name from a word invented by their colleague Maksym Nakonechnyi. It fuses the words “militant” and “anthropos,” which, in their eyes, equates to a human reshaped by conflict. Militantropos is composed of ordinary and extraordinary lives, of landscapes and steady camera shots, all caught within the gravitational pull of war. The film is a collective mosaic, each scene placed one after the other with no direct link or particular location in Ukraine. There is also no narrative guidance.

It doesn’t dramatize Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; it dissects its imprint on the human condition. People flee, lose, resist. The directors describe it as an “encounter with possible non-existence”—an experience of facing death that transforms not only individuals but the collective itself.

What Militantropos offers Europe is not reportage, but recognition. War, it suggests, is no longer a distant phenomenon observed from the safety of peacetime societies. It is universal, irreversible, and here.

A burning earth

If Militantropos charts the transformation of the individual, Songs of a Slow Burning Earth turns its lens toward collective consciousness. Directed by Olha Zhurba, the film unfolds as an audiovisual diary of the first two years of Russia’s full-scale invasion. It gathers fragments: faces, landscapes, and silences. There is no central character. The protagonist is time itself—how it stretches and numbs.

In the film’s description, the war “became normalized.” That word, stripped of sentiment, is where Zhurba’s project locates its emotional weight. Her images do not dramatize trauma but document its absorption into everyday life. Against this backdrop of exhaustion, the director observes a generation that still imagines a future.

Zhurba quotes the 33-year-old poet and soldier Maksym “Dali” Kryvtsov, who was killed in 2024: “When they ask me what war is, I’ll answer without hesitation: it’s names.” The line distills the film’s central tension: between anonymity and remembrance, between collective and intimate lives.

For European audiences, Songs of a Slow Burning Earth reads as a warning, suggesting that Europe’s identity, so often debated in bureaucratic terms, is being redefined by those living at its frontier.

Fathers and daughters

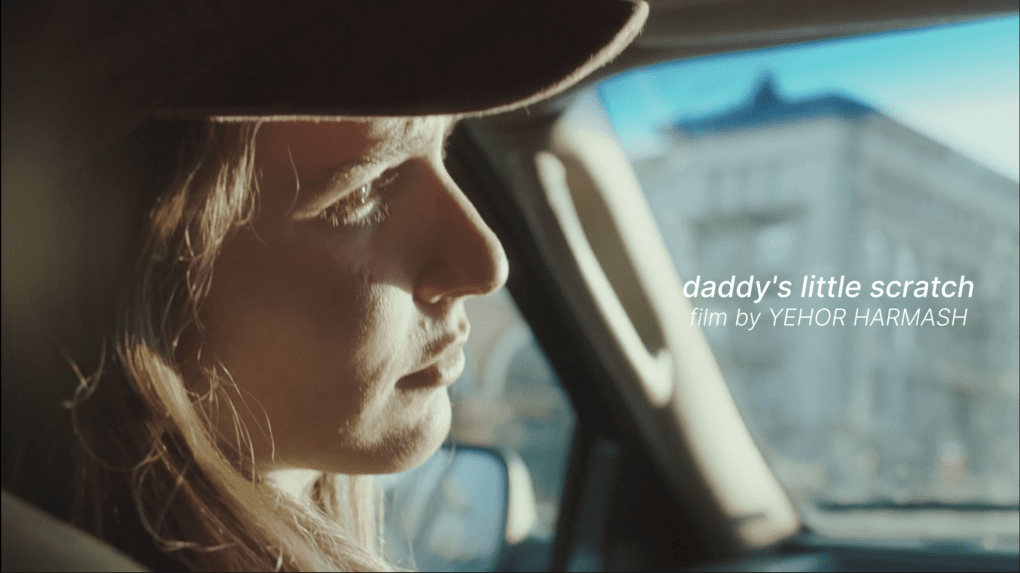

In Daddy’s Little Scratch, Yehor Harmash turns from the public to the personal. The short film follows a girl, Slava, spending a single day with her father, Roman, who is home on leave from the front. They travel to return an expensive carpet he bought for her, a simple errand that becomes a study in estrangement.

Years of absence have fractured the affection between father and daughter. What remains are gestures or attempts at care that fail to bridge the silence.

Harmash, who based the story on his own experience with a father who served in the army, treats war not as a backdrop but as a distance or echo. The camera observes how love persists yet transforms under pressure. The result is a quiet film that refuses sentimentality.

Europe’s expanding frame

The inclusion of these three films on the European Film Awards shortlist marks more than recognition of national cinema; it signals a shift in Europe’s cultural center of gravity. Ukraine is not being invited into European culture; it is, in some ways, redefining it while also complexifying what it means to be European.

Since 2022, Ukrainian filmmakers have become fixtures in international festivals from Berlin to Locarno, their work forcing curators and audiences alike to reconsider what constitutes the “European experience.” When Dmytro Sukholytky-Sobchuk’s Pamfir was nominated for a European Film Award two years ago, it hinted at this transition.

Cinema has long served as the continent’s mirror, reflecting both its fractures and its ideals. This year's Ukrainian entries offer no comfort, no polished image of endurance. They show a Europe under strain, insisting that the European project remains alive precisely because it can hold such contradictions.

-29ed98e0f248ee005bb84bfbf7f30adf.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)