- Category

- Culture

“Where are we now?”: An Exclusive Interview with Photographer Boris Mikhailov on Ukraine’s Past and Present

Boris Mikhailov: Ukrainian Diary—a color-rich portrait of post-Soviet Ukraine—opens in London after debuting in Paris in 2022. Ukrainian Photographer Boris Mikhailov and Paris-based curator Laurie Hurwitz reflect on the decades-long artistic journey that shaped the exhibition, from the radical Kharkiv School of Photography to the transgressive Case Study series, and on creating art in the midst of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

The famed Ukrainian photographer, Boris Mikhailov, answers our questions in deliberate paragraphs from Berlin, dividing his time between there and Kharkiv.

Mikhailov’s vast body of work, composed of a series such as Case History and At Dusk, made him the photographer we know so well today: voracious, ironic, romantic, prophetic, and sometimes cruel.

His career began in the 1960s, when simply owning a camera could invite suspicion. Dismissed from his job as an engineer after the KGB discovered nude photos of his wife, Vita Mikhailov, in his lab, Mikhailov continued photographing what a Soviet lens would hide—the imperfect and often, the absurd.

For the second edition of the exhibition, curator Laurie Hurwitz writes from London. The first, iteration of Boris Mikhailov: Ukrainian Diary, at Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP), ran in Paris from September 2022 (in the year of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine) to January 2023.

This recent exhibition, at The Photographer’s Gallery, opened in London on October 10. After the opening of the second edition, Hurwitz writes eloquently about the show’s evolution.

She recalls how the exhibition changed through constant rethinking. The initial 600-photo plan was pared down as Hurwitz, Mikhailov, and his wife, Vita, worked in Berlin, endlessly refining. “Nothing was ever fixed—the exhibition remained open and alive,” Hurwitz says.

Kharkiv, Mikhailov’s hometown, still endures near-daily missile and drone attacks. Once the cradle of the Kharkiv School of Photography—the underground collective that rebelled against Soviet realism with irony and experiment, now straddles the front line. When the war began, the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography evacuated its archive to Germany and Austria to save it from bombardment.

Boris Mikhailov, writing from Berlin

You lived through the 1990s in Ukraine. How did that period influence your style?

Boris Mikhailov: The 1990s in Ukraine were a long goodbye to Soviet life. My work is inextricable from life, so of course it was influenced in myriad ways. After the collapse of the USSR, I began looking for ways to document how everything was changing. In 1991, things were falling apart.

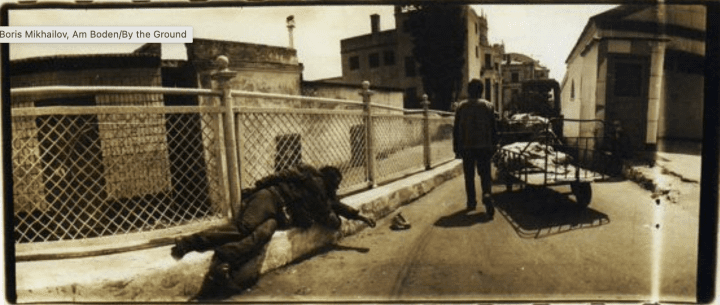

The streets were overflowing with poverty. That was when I made By the Ground, my first panoramic photos. It begins with a photo of a woman lying on the sidewalk—one of the first homeless people I had ever seen.

I felt the need to photograph everything, to shoot and shoot and shoot life at ground level. I also made At Dusk and Green, which were more about the passage of time, like moss growing slowly over the ruins of Soviet life. In the Soviet period, we knew who the heroes were—they had been assigned to us. But in the early 1990s, that idea had collapsed.

Now, there could only be an antihero. That was the starting point for a different kind of series, I Am Not I, a search for a new protagonist. I was drawn to figures from Western mass culture, like Rambo. I photographed myself trying on their identities, as if testing whether they fit this strange new reality.

Later, I captured a situation in transition. In 1997–98, after a year on a stipend in Germany, I returned to Kharkiv and found the city transformed.

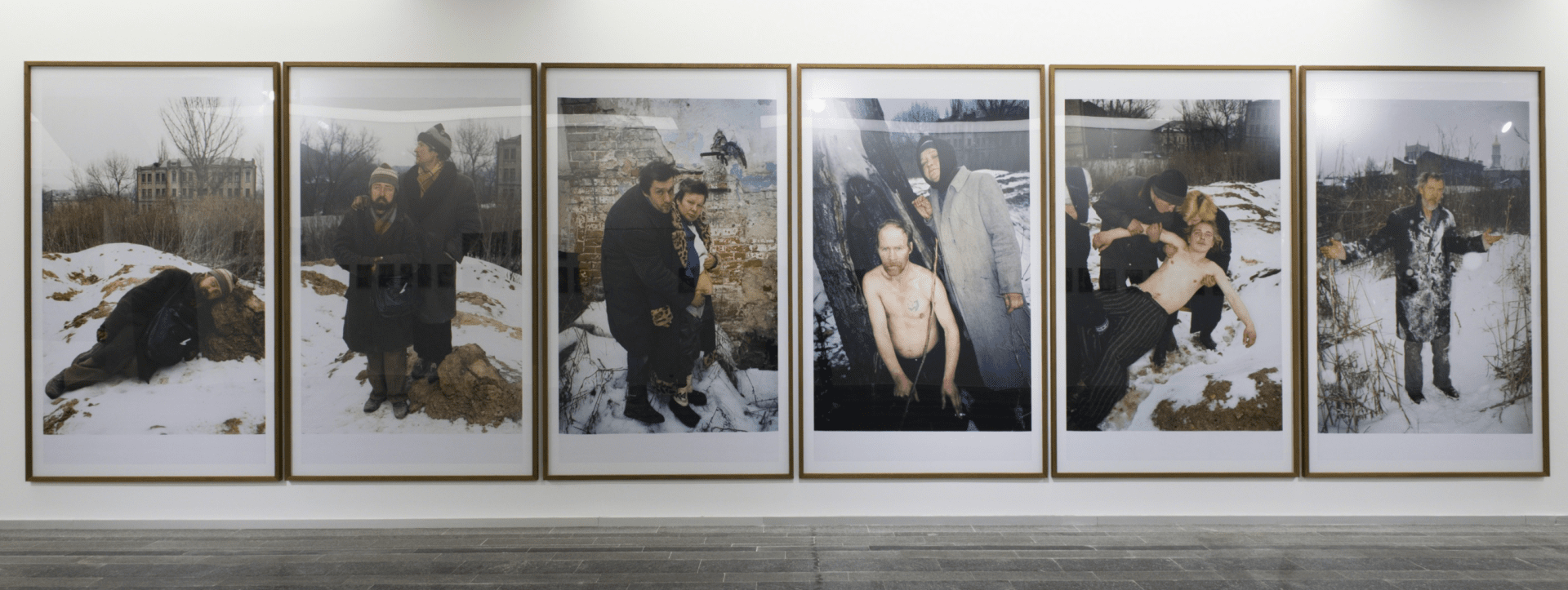

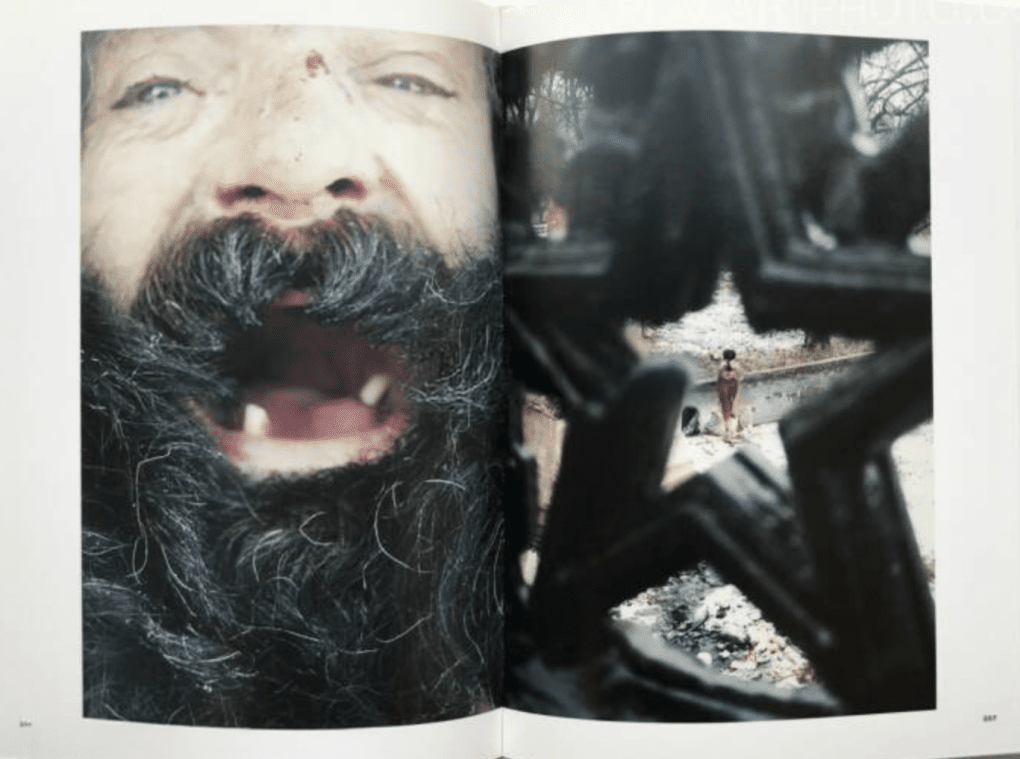

People seemed wealthier, the city more beautiful, the streets full of cars. But I also noticed the shadows—more and more homeless people, ignored or unseen. That’s when I began Case History, a kind of requiem for those disappearing from view. In their nakedness and defenselessness, I saw something even more tragic. The scars on their bodies told their own story. I felt a responsibility to document this reality.

When Vita and I were working on the series, I often thought of the American Depression—how the US government had commissioned photographers to capture what was happening. We had no such commission; we did it because we had to.

Two years later, I began photographing the city again, now in an independent Ukraine shaped by Western capitalism. Everything was for sale. Billboards, plastic goods, tote bags, vendors calling out at tram stops—it was a new visual language of transition: East and West, past and present, dissolving into each other. Commerce moved into the streets. Old women pushed carts full of goods, calling out “Tea, coffee, cappuccino…” in the underpasses.

That became the title of the series: Tea, Coffee, Cappuccino… We’d never heard of cappuccino before. It was a small thing, but it was a sign of the times. Behind it all was Kharkiv—the city that shaped me, full of tension, energy, and contradiction. My first teacher in art wasn’t a person—it was the building I grew up in there: a massive grey constructivist structure from the 1930s, full of square planes and dark hollows. It reminded me of Malevich’s Black Square. That building shaped how I saw and measured the world. It represented Soviet progress, but also its absurdity. That geometry and that tension are still in my work.

In your recent work, you often use a split screen, as in the installation Our Time is Our Burden. Is there a reason for this approach?

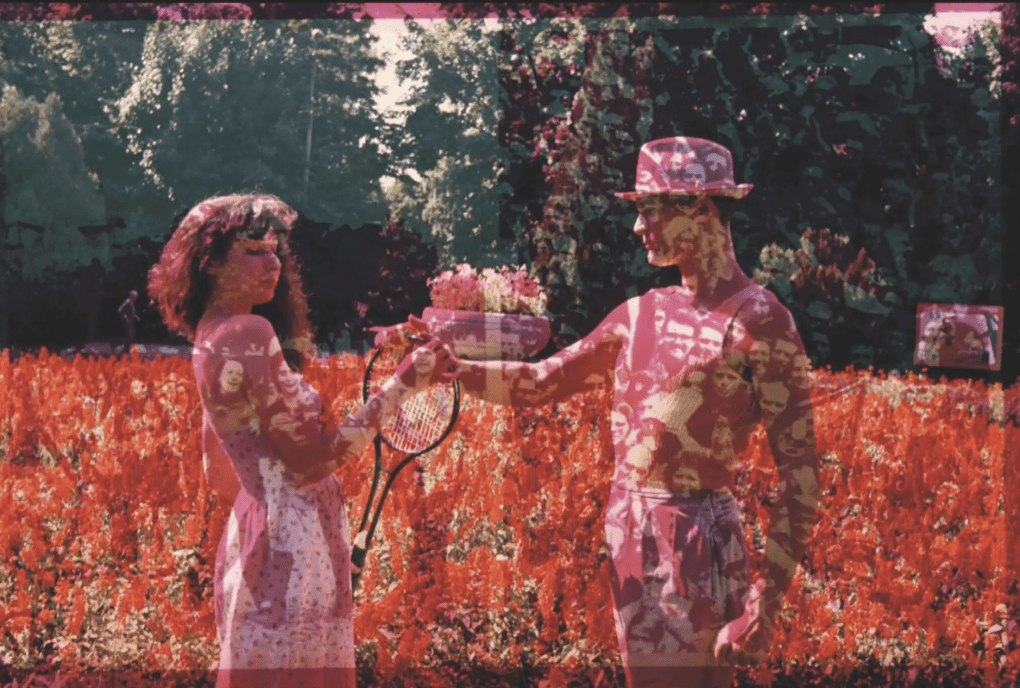

Boris Mikhailov: The idea of duality has been with me since the 1970s. It first emerged almost by accident, with Yesterday’s Sandwich. I was self-taught and not especially disciplined; I would develop rolls of film and toss the slides onto the bed. One day, two of them stuck together, and suddenly I saw something unexpected: a layered, metaphorical image.

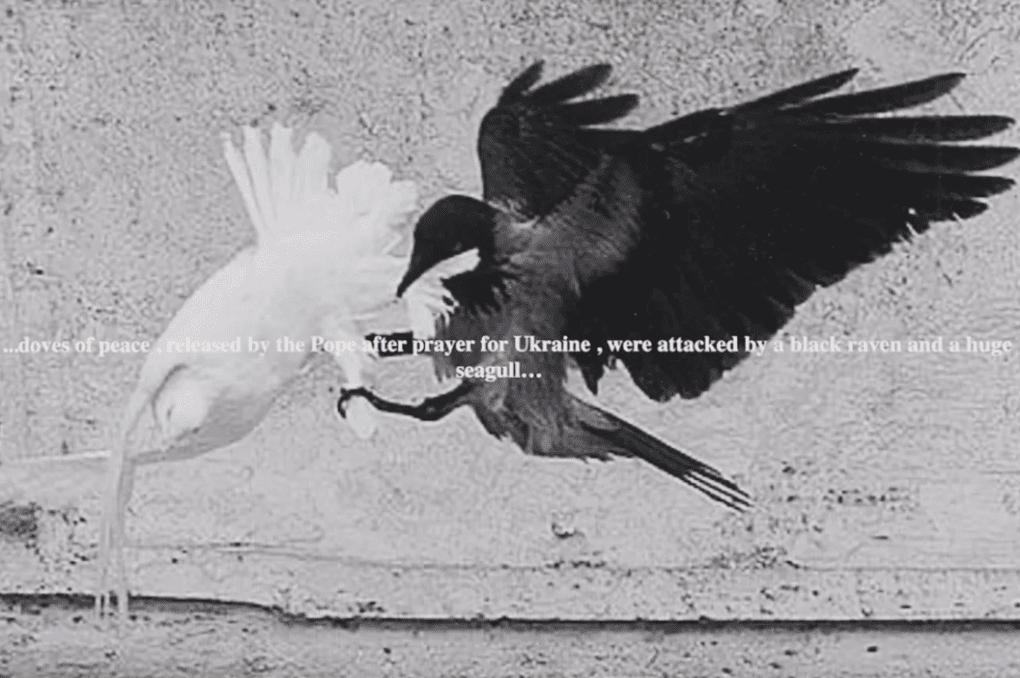

From that moment on, I began working with superimposition, layering one image over another to create new meaning. I call it “programmed accidentality.” Often, I didn’t even know why I was taking a particular picture, only that someday it might find its counterpart, and together they would enter into dialogue, often through contrast or contradiction. That sense of duality—of things existing in tension—was deeply embedded in Soviet consciousness in the 1960s and ’70s. We lived with overlapping realities: the past and the present, totalitarianism and a democratic façade. The transparency of those double images became a kind of political metaphor. Life wasn’t linear or clean; it was layered, conflicted, and full of unseen connections.

This visual logic continues today in my diptychs and split-screen videos, like The Temptation of Death (2019) and, more recently, Our Time is Our Burden. These works bring together images from different times and places—old and new, memory and present experience—fragments of a personal story assembled into a kind of visual novella. The diptych, like the pages of an open book, creates space for comparison, contradiction, and connection. Perhaps I use this format now because a single image is no longer enough. It takes two to hold the world’s tension.

There’s an old parable about a group of blind men who each describe a different part of an elephant—one feels the trunk, one the tail, one the tusk—and each is convinced he understands the whole. But none of them do, not alone. I think about that often. A single image can’t contain the truth. I need the sum of the images, the vibration between them, to create space for doubt and for possibility.

You are known as an innovative photographer. Do you think it is more difficult to introduce innovative approaches in photography today?

Boris Mikhailov: For me, photography is closely tied to a sense of freedom—like that expressed by the famous Ukrainian painting Zaporozhian Cossacks by Illya Ripyn. It’s about liberation, yes, but also about the essential feeling of being a Ukrainian citizen. And innovation, in my case, comes from that freedom—not just technical innovation, but a theoretical freedom, a freedom of vision. I was an engineer who became a photographer. In the 1960s, I worked at a research institute, like many others in Kharkiv, and we had a photo lab. We started using those spaces to make art. There was no demand for photography—no money, no commissions, no institutions. And strangely, that gave us freedom. We were unofficial. Nobody cared what we did, so we could do anything.

With the Thaw , the old taboos began to shake: criticism of the regime, religion, erotica, mysticism—things we hadn’t been allowed to touch before. So we touched them.

There was nothing happening in the streets except for parades and official events—nothing to photograph. But we made something out of nothing, and everyone saw that “nothing” differently. We experimented in the darkroom—layering images, manipulating prints, trying to make photography do what painting could do. We were inventing new worlds, breaking the rules, breaking the grid—because everything around us already felt broken.

I can’t speak for other artists, but in my own practice, innovation often comes through chance. A photographic accident can be more interesting than a carefully planned collage. I was thinking about this recently: you photograph one subject, then another, and when you place them side by side, an unexpected connection appears. That unintentional link can become a story—sometimes even a story about life in its entirety. For me, that’s the essence of photography: chance transformed into meaning. Time also changes everything. It dictates what matters—what themes to explore, what aesthetic to follow, even what equipment to use.

That’s how many of my historical series came about. In the 1960s and ’70s, the arrival of color slide film was revolutionary—suddenly, color entered a world that had been mostly black and white. In the early 1990s, I began using panoramic cameras for By the Ground and At Dusk. Later, in 1997–98, I used Kodak color film for the Case History. These technical shifts weren’t just formal; they reflected a change in perception, in how I was experiencing and responding to the world around me. So yes, innovation is always possible, but sometimes, it’s about staying open to accidents and to what time, chance, and vision offer you.

Do you think there is a distinct Ukrainian color palette in your work? And if so, how has it evolved?

Boris Mikhailov: I wouldn’t say I intentionally use a distinctly “Ukrainian” palette, but color has always played a central and evolving role in how I reflect life in Ukraine—especially during and after the Soviet period. There is, of course, the Red series—a fragmented grid of over 70 images from the late 1960s and ’70s, all featuring the color red. At the time, red was inescapable—a powerful symbol of the Russian Revolution, Soviet ideology, and collective identity.

Everyone associated it with communism, but few noticed just how deeply red had seeped into our everyday lives. It was everywhere: in uniforms, flags, posters, curtains, and playgrounds.

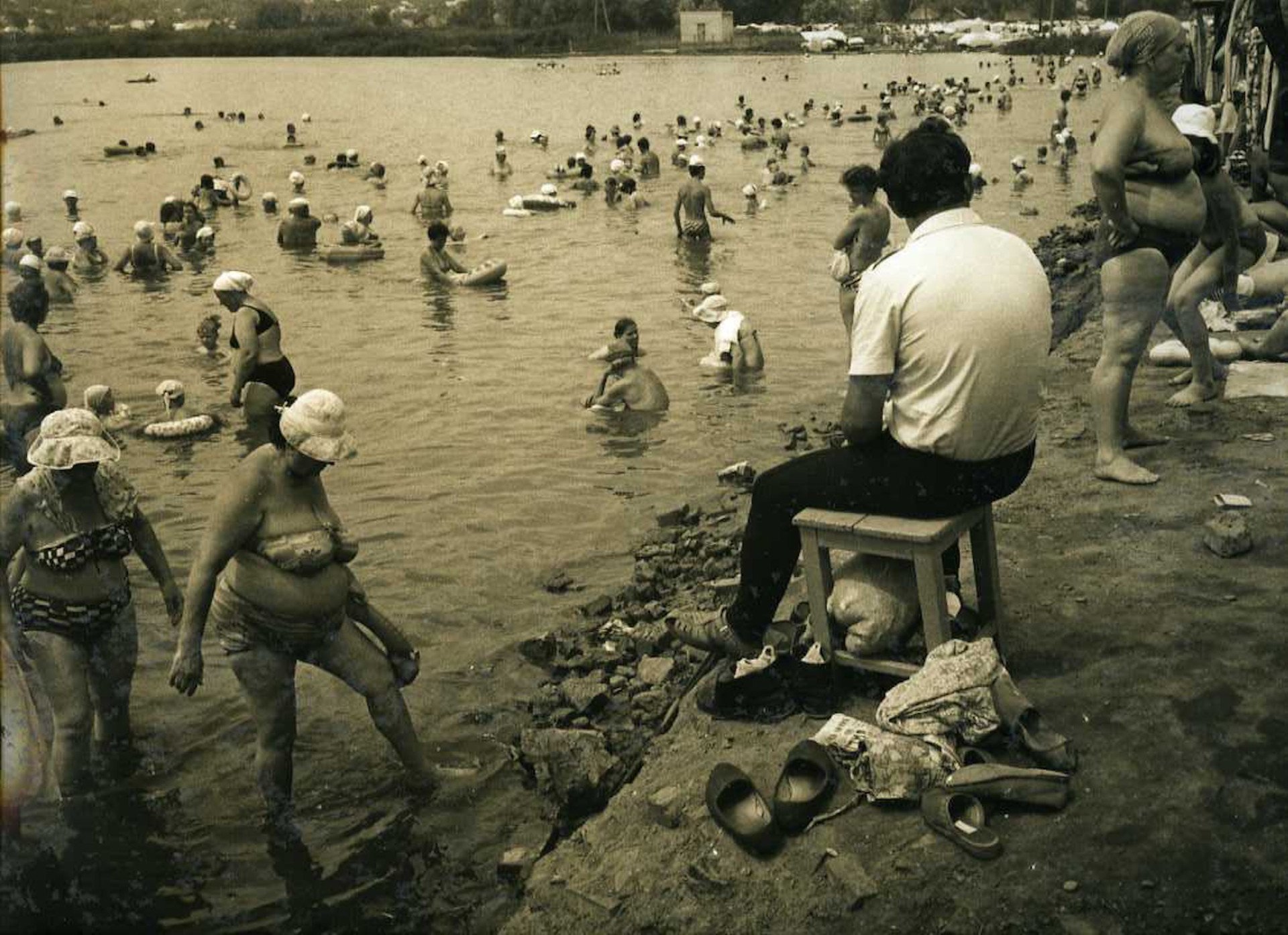

In the 1970s, I began hand-coloring black-and-white photographs with aniline dyes—garish, kitschy tones that mimicked how Soviet propaganda tried to artificially brighten what were, in reality, dull, gray, oppressive scenes. That color was both ironic and revealing. Oddly enough, this doctoring of the photograph, this awkward, vulgar coloration, brought the image closer to reality. It made it unacceptable, because that’s how life really was. In series like Berdyansk Beach and Salt Lake, I used sepia to evoke a sense of nostalgia—to make modern images feel like they belonged to another era. I call this effect “parallel photo-historical association.” When something new looks old, it raises the question: where are we now? When I made At Dusk in 1993, I tinted the prints cobalt blue—the color of blockade, of hunger, of war. In 1941, I was three years old. I still remember the sirens, the bombings, the searchlights cutting through the deep blue night sky.

Blue, blue, light blue… It stayed with me—a color linked to fear, memory, and silence. And then there is gray—the color of nothingness and stagnation. Sometimes I photographed things so empty, so forgotten, it felt as if even color had abandoned them. The gray wasn’t an aesthetic choice—it was existential. It reflected a country caught in a frozen everyday, stalled in time. I once wrote on a photograph: Everything here is so gray in gray that there isn’t even anything to color. So, in the end, maybe there is a Ukrainian palette, but it’s a palette made from lived experience. Color becomes not just a formal choice, but a way of recording history.

Laurie Hurwitz Curator of Boris Mikhailov: Ukrainian Diary

Laurie Hurwitz: We made the conscious decision to remove more playful series, such as Football, and instead foreground The Theater of War, photographed in Kyiv in December 2013 during the early days of the Maidan protests. These images, charged with a palpable tension and almost theatrical composition, resonate with a foreboding anticipation of the conflict to come.

Boris and Vita both saw this series as a direct reflection of the war’s origins. In a deliberate curatorial dialogue, The Theater of War was installed opposite Tea, Coffee, Cappuccino, a vivid portrayal of the burgeoning small-scale capitalism in post-Soviet Ukraine, populated by street vendors, branded plastics, and a new vernacular of survival.

Nearby, the seminal Case History series revealed a grimmer reality. Created in the mid-1990s, I documents Kharkiv’s homeless population in the aftermath of the Soviet collapse, an unflinching and profoundly empathetic study. Mikhailov photographed over 400 individuals, engaging with them through payment, sustenance, and carefully composed tableaux that evoke the solemnity of religious painting. In the exhibition, we juxtaposed a handful of these monumental photographs with more than one hundred small test prints, amplifying the sheer scale and intensity of the suffering portrayed.

Together, these works—spanning decades—form a powerful narrative of a society in flux, suspended between history and the present, despair and resilience.

What was the first step in approaching such a large archive of Mikhailov’s work?

Laurie Hurwitz: The first step in shaping the exhibition began more than a year before its opening in Paris. I traveled to Berlin, where Boris and Vita live, equipped with several maps of the museum spaces and a provisional framework. But from the very beginning—particularly through long, searching conversations with Vita, my ultimate partner in crime, whose clarity, intuition, and grace shaped every part of this project—those early ideas were quickly undone.

We spoke constantly, questioned everything, rethought structure, content, tone. I made nearly a dozen trips to see them, and each time we spent long days looking through images, changing our minds, arguing, laughing. We would rearrange sequences, double back, and start again. Nothing was ever fixed, and that was essential: the exhibition remained as open, searching, and alive.

Boris is extraordinarily prolific. For the first and largest iteration of the exhibition, we included twenty-five series—more than 600 photographs, in color and black and white, large and small—works that stretch and subvert the photographic medium with restless invention. And still, there were many more we couldn’t include. Across months of work, we looked through thousands of images, constantly uncovering unfamiliar pieces, new sequences, and unexpected threads.

The process unfolded during a particularly charged moment. Just a few months before the exhibition opened, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Relatives from Kharkiv came to live with Boris and Vita in Berlin. Grief, disorientation, and a constant sense of urgency were in the air. That heightened emotional atmosphere filtered into every part of our process, intensifying the choices we made and deepening our sense of responsibility.

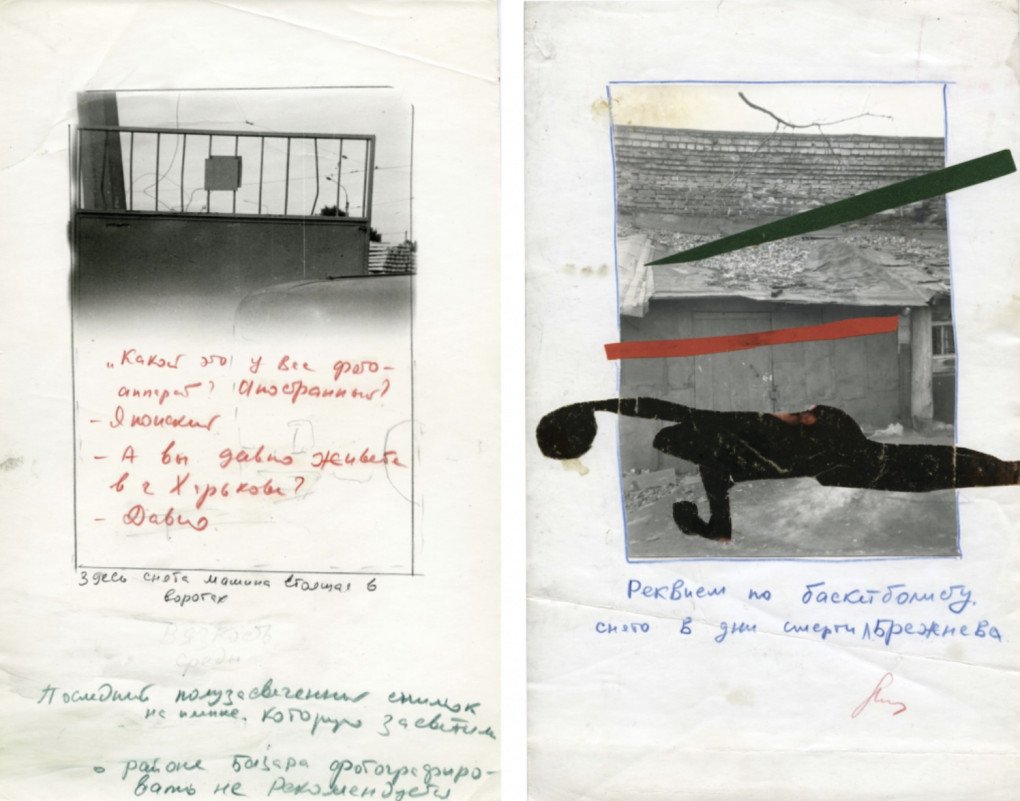

That emotional intensity made the experience of working together more necessary, more human, more profound. In addition to Mikhailov’s most iconic series, we included several lesser-known works that reveal his early conceptual thinking. Viscosity, created in the 1980s, for instance, merges image and text in a rough, intuitive format that anticipates the artist’s book. Photographs are glued to paper, surrounded by scribbled fragments—banal, poetic, philosophical – that don’t explain the images but exist alongside them, forming a dual voice that reflects the stagnation and coded absurdity of Soviet life.

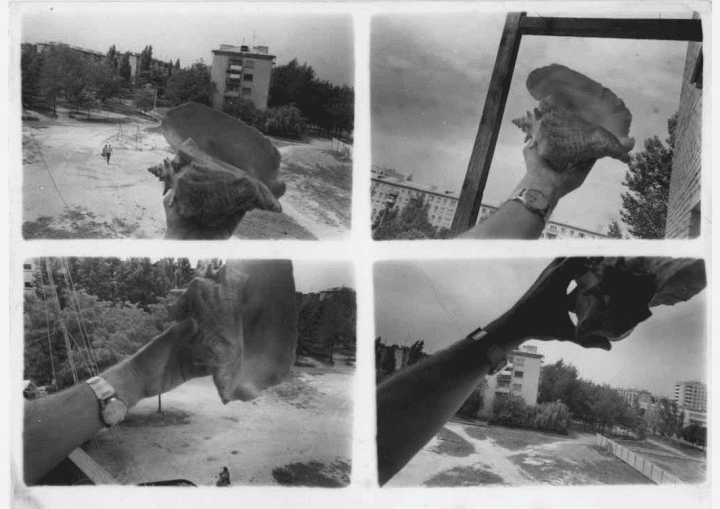

We imagined new configurations for the Series of Four, which emerged from a practical limitation—a lack of small-format paper that led Mikhailov to print four images per sheet. When drawn from the same time and place, they suggest a compressed, fractured view of reality. That accidental structure became method: a cinematic way of resisting linear narrative, embracing ambiguity, and reflecting the drab repetition of daily life in late Soviet Kharkiv.

From the beginning, we conceived two video works as conceptual bookends. At the entrance, Yesterday’s Sandwich—a seminal project from the late 1960s—presents a hallucinatory sequence of double exposures set to music by Pink Floyd. These psychedelic, surreal images, rejecting Soviet visual orthodoxy, open up a new, rebellious visual language. At the exit, Temptation of Death (2019) offers a quieter, meditative counterpoint. Combining images from a crematorium in Ukraine with intimate portraits and cityscapes, it evokes the myth of Charon, ferryman of the dead, and a journey through time, loss, and transformation. Together, these two works, created nearly fifty years apart, frame the exhibition with a meditation on mortality, reinvention, and the fragile persistence of life.

Throughout this long process, Boris and Vita were incredibly generous and accompanied me in ways of working that were playful, irreverent, yet always deeply intentional. They taught me to dwell in contradiction, to hold doubt, to embrace complexity. That spirit runs through the exhibition, including its current adaptation for London’s Photographers’ Gallery.

Did you need to explore the Ukrainian cultural or economic context in depth?

Laurie Hurwitz: Absolutely. To engage deeply with Boris Mikhailov’s work, understanding the cultural and political context from which he emerges is indispensable. Trained as an engineer, Mikhailov is a self-taught photographer. Early in his career, he was given a camera to document the state-owned factory where he worked, but instead used it to take nude photographs of his wife. When these images were discovered by KGB agents, he was promptly fired.

At the time, photographing the naked body—and unflattering scenes of daily life—was strictly taboo. Artists who strayed from the official Soviet aesthetic faced harsh consequences: surveillance, harassment, arrest, and even imprisonment. Mikhailov was no exception. He was trailed in the streets, harassed, his cameras smashed, and his film routinely confiscated or destroyed.

The constraints of Soviet censorship also shaped Mikhailov’s use of coded visual language. In the 1970s, with real news scarce and open discourse suppressed, artists resorted to hidden meanings and encryption to explore forbidden subjects such as politics, religion, and nudity.

Mikhailov’s early series Yesterday’s Sandwich exemplifies this approach. It defied official tenets by embedding multiple layers of coded allusions, forcing viewers to look beyond surface appearances to uncover deeper truths. His embrace of “poor quality” or statistically average photographic techniques was another act of quiet rebellion.

Mikhailov recognized that aesthetic “imperfections”—damaged prints, grainy textures, or crude compositions—could undermine official ideology by introducing a sense of eeriness and unease. Before fully dedicating himself to photography, he worked in cinema and created a film based on archival documentary photographs from his factory. Though many of these images were degraded or flawed, their very imperfection amplified their emotional power and sense of dread. Through such methods, Mikhailov intentionally violated the rigid canons of Soviet photography, producing work that was “wrong” in subject and style—but profoundly truthful in its portrayal of lived experience.

Building on this foundation of subversion, the series created after the Soviet collapse marks a striking shift in both form and content. Mikhailov employed a panoramic camera—a format traditionally reserved for grand, romantic landscapes—to capture the bleak, fractured street life of post-independence Ukraine. These images challenge the hopeful narratives of freedom and renewal, instead presenting a raw portrait of devastation and dislocation.

In short, engaging with Mikhailov’s oeuvre demands not only a knowledge of Ukrainian history and politics but also an appreciation of the subtle visual codes and poetic strategies he developed in response to repression. It is this tension between censorship and creativity, official narrative and personal truth that animates his work and continues to resonate today.

To further illuminate these complex historical layers, for the book and select iterations of the exhibition, we also prepared a detailed timeline outlining the evolution of Ukrainian history alongside key moments in Boris Mikhailov’s artistic journey. This timeline provides vital context, helping viewers and readers trace the interwoven relationship between the country’s turbulent past and Mikhailov’s evolving visual language.

Was there any series you hesitated to include in the exhibition?

Laurie Hurwitz: No. Boris’s work frequently ventures into uncomfortable, even unsettling terrain, but that discomfort is intrinsic to its power. Some series are raw, confrontational, and bleak, yet always profoundly human.

The real challenge was not whether to include certain works, but rather how to present them with the respect their complexity demands. This often meant careful consideration of placement, installation, pacing, and the dialogue between series, allowing some pieces the space to resonate quietly, while others were intentionally set in stark conversation.

Did you design the exhibition as a journey through Mikhailov’s work, or was there another goal in mind?

Laurie Hurwitz: The exhibition unfolds largely as a chronological journey, tracing the development of Mikhailov’s practice and artistic concerns over time. This approach enabled us to bring together an exceptional breadth of his series in one space, crafting a nuanced narrative that acknowledges both continuity and rupture within his oeuvre. Yet, we consciously departed from a strictly linear narrative at pivotal moments, allowing thematic and formal resonances to emerge across different periods.

Mikhailov’s work inherently resists conventional storytelling; it is cyclical, marked by recurring motifs and an interrogation of its own internal logics. Thus, while chronology provides a structural framework, the exhibition embraces shifts in tone, medium, and perspective, fostering a dynamic dialogue between works. Central themes—heroism, failure, power, the body, identity, absurdity, ideology—recur throughout, not as definitive conclusions but as open-ended provocations that invite sustained contemplation. In this way, the exhibition operates as both a temporal sequence and a constellation of moments—fragmented yet interconnected—that collectively evoke the complexity, contradictions, and richness of Mikhailov’s visionary practice.

-f223fd1ef983f71b86a8d8f52216a8b2.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-d3a157681c162cfaad134697053ff774.jpg)