- Category

- Culture

Legendary Photographer Oleksandr Glyadyelov Opens Major Exhibition 'For Ukrainians About Ukrainians’

-c0ff8b1aa9c90939807f99ea2024c861.jpg)

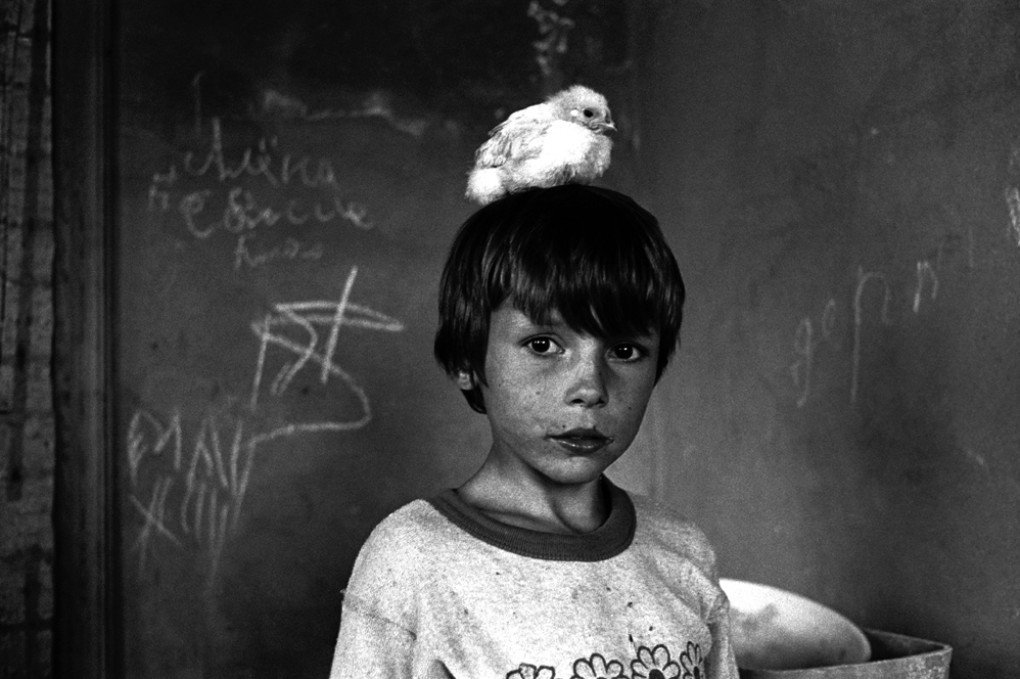

Glyadyelov’s new retrospective spans 35 years of Ukraine’s momentous history. But it is in the quiet, lived moments—the exhaled breath of a city under fire—that his photographs truly resonate.

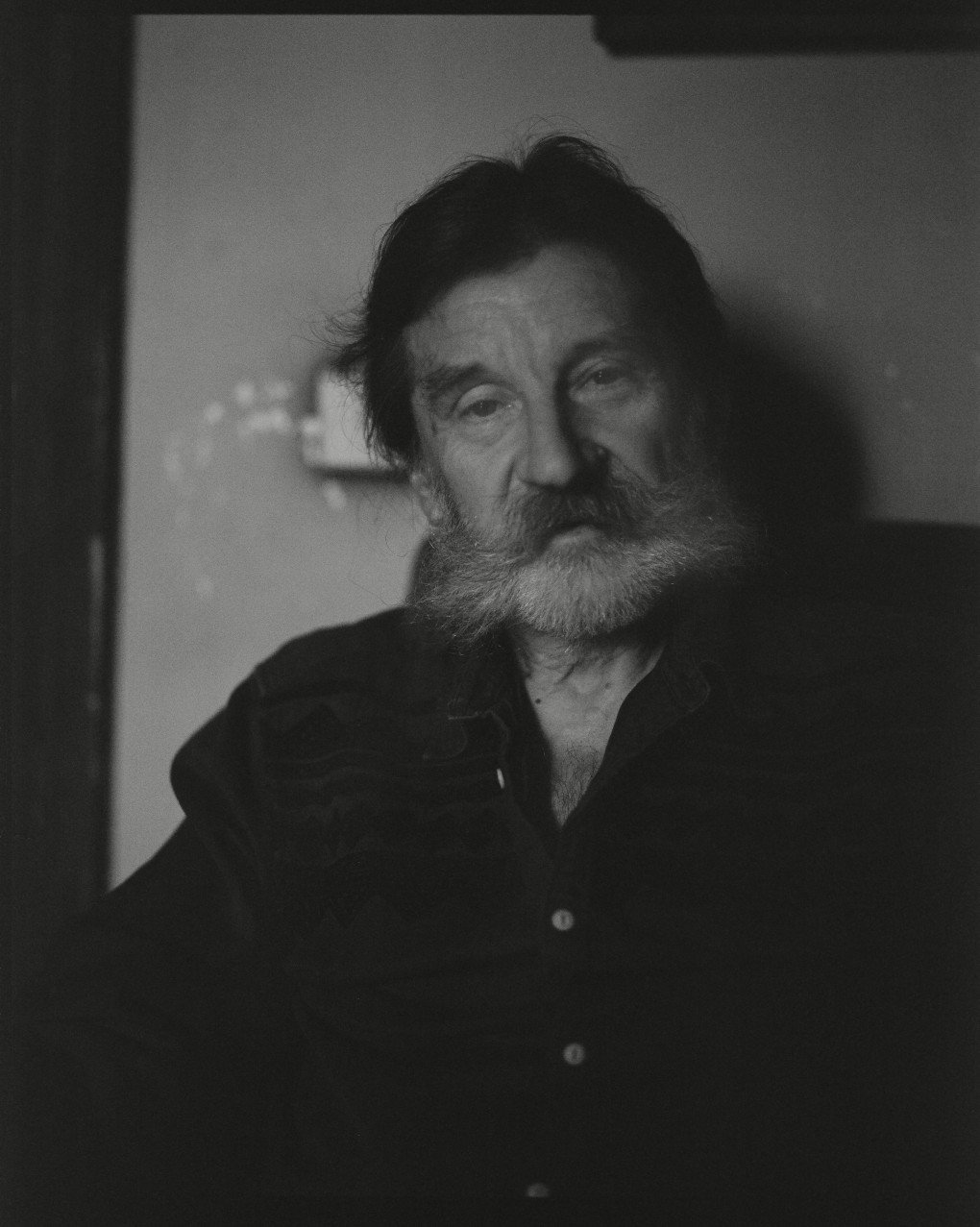

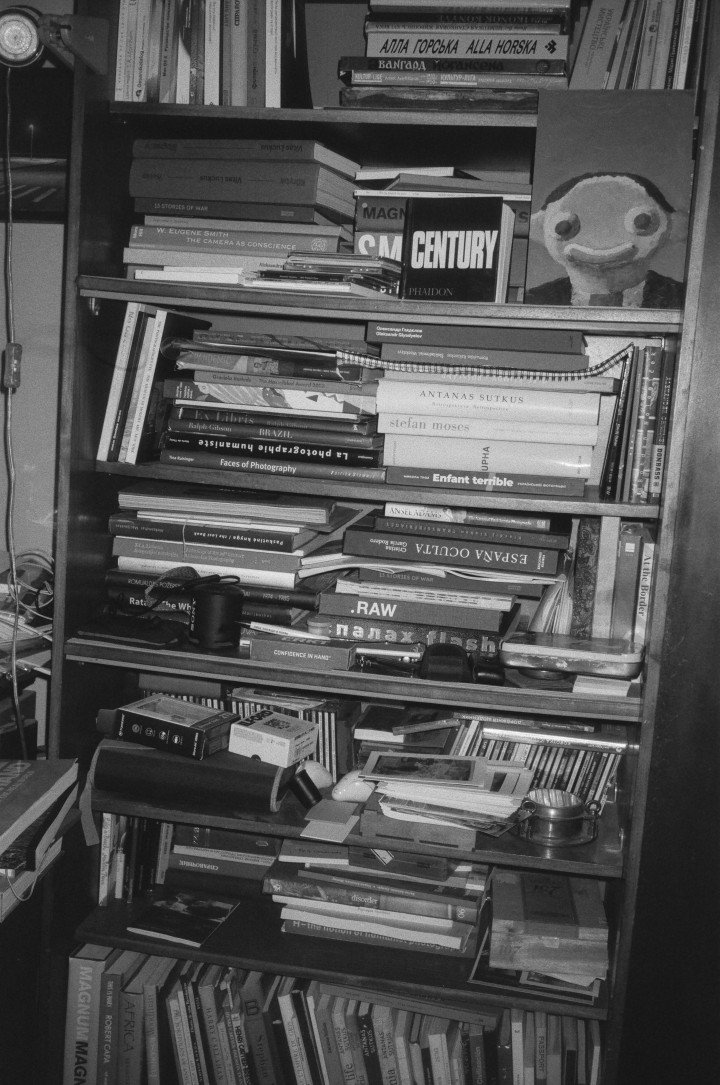

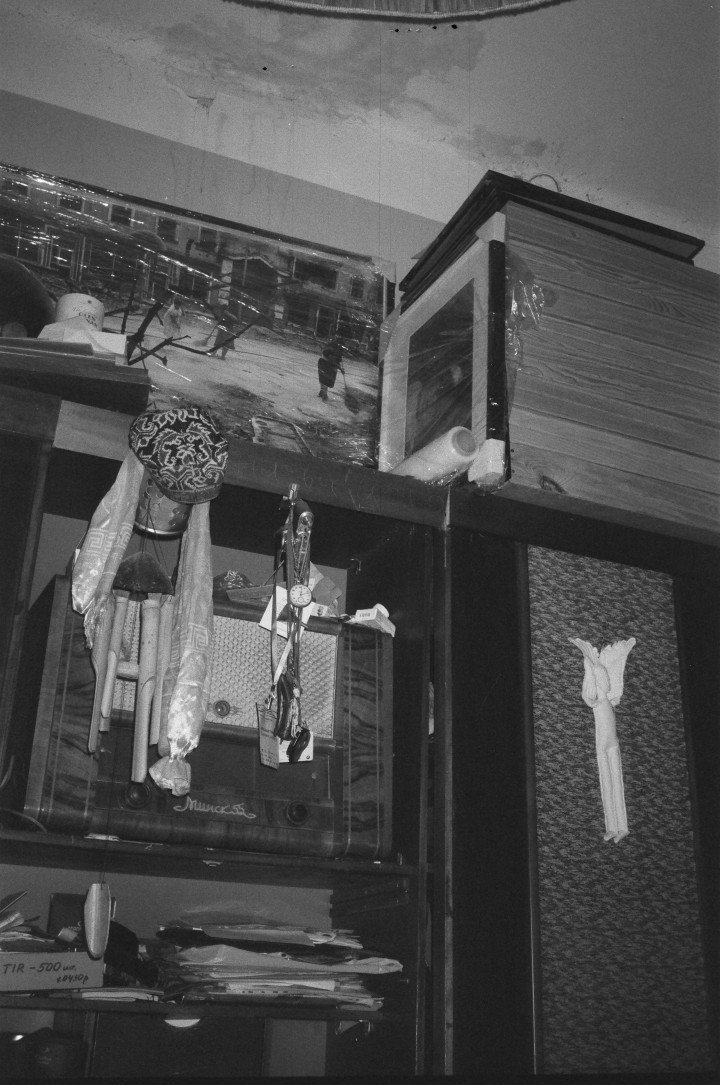

“Gifted people exist,” says Oleksandr Glyadyelov at our first meeting, commenting on a collection of work by the American photographer Francesca Woodman. Standing in his living room, tying up his long grey hair, the sunlight filtering in illuminates shelves crammed with photobooks, wine, and flak jackets.

Ukraine through Glyadyelov’s lens

Glyadyelov’s exhibition "And I Saw" opened on September 5 at The Ukrainian House in Kyiv. It is essentially a retrospective that includes 323 black-and-white photographs taken exclusively in Ukraine over the past 35 years.

Dubbed “Ukraine’s photobook,” the exhibition stands as a chronicle of the country’s extensive narrative snatched away from any sort of Russian lens. Glyadyelov serves as Ukraine’s critical swivel, history circling his Leica M6. What is then unraveled, stretched out onto three levels of the exhibit, is proof of Ukraine’s resistance—not, as is often falsely perceived in the West, something born in 2022, but a force that has existed for centuries.

"And I Saw" is being held at the Ukrainian House in Kyiv—a circular structure that looks a little like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim museum. It is near Dynamo Stadium, where the special police Berkut violently dispersed protesters from the central Maidan Independence Square on November 30, 2013. It became a battleground, birthing some of the strongest imagery of the 2014 Revolution of Dignity. The Ukrainian House is also a short walk from Maidan Square itself.

Glyadyelov was there for all of it. Beginning with the period known in Ukraine as “the 90s,” when a large swath of society delved into widespread poverty caused by hyperinflation, which then incurred a dramatic decline in living standards.

Then he covered the 2004 Orange Revolution, the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, and the subsequent fight in the East of Ukraine against Russian-backed forces, and finally the Russian 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine, amongst other defining historical events.

“What would you like to drink?” asks Glyadelov, “Red or White?”

From Diane Arbus to Ilovaisk

We sit down, and Glyadyelov takes off his glasses and rests them on his thigh. The living room testifies to his established presence within the world of contemporary photography. He grew up looking at images by Lee Friedlander, Diane Arbus, Eugene Smith, Ansel Adams, and the famed photo agency Magnum.

“I have to say Diane Arbus' photographs moved a lot of my generation. We had a book with her pictures, and the book was passed around many photographers' apartments. It was the end of the Soviet Union.”

Today, many young Ukrainian photographers would put “Sasha,” as he is known, on their list of influential photographers, just as he had put Arbus on his.

When Glyadyelov first started using a single-reflex Leica, “it was in 1992,” he recalls. He never uses lens caps; “you have to be ready,” he states. Manifestly, he’s a true advocate of this: his M6 was slung across his chest when he came to pick us up downstairs from his apartment.

His presence, tall and rail-thin with an ample moustache and beard, gives him the air of a photographic guru. He is surrounded by objects that are mainly gifts from friends, often other photographers. “I have a lot of friends who are good photographers,” he smiles.

Gifted people have always accompanied Glyadyelov. In the rare photobook Ilovaisk, published by Blank-Press in 2022, he shares pages with Ukrainian photojournalistic royalty: Maxim Dondyuk, Markiyan Lysoyko, and Maksym Levin (who was executed by Russian forces in 2022).

The book, which relates through a mix of colour and black and white imagery the 2014 Donbas war against Russian troops, concentrates on one particular moment: from August 24 to 26, 2014, Ukrainian troops were surrounded by the Russian forces, trapping them in the “Ilovaisk Cauldron.”

Then, on August 29, Russian leader Vladimir Putin falsely claimed a humanitarian corridor had been created for Ukrainian forces to retreat. On August 30, 2014, Russian forces ambushed Ukrainian troops in the corridor, killing between 366 and 1,000 soldiers. Glyadyelov left three days before the encirclement of Ilovaisk as he was wounded.

How curators Oleg Sosnov and Tetiana Lysun brought a vision to life in wartime Ukraine

The curators of “And I Saw,” Oleg Sosnov and Tetiana Lysun, are also Glyadyelov’s friends. Sosnov met Glyadyelov through the iconic French photographer Antoine Dagata in 2011, but the idea to create a huge retrospective had already started to foment in Sosnov’s mind. The place he thought would be the Ukrainian House.

Sosnov grouped the funds for the exhibit, step by step. He describes himself as conservative, though behind his short, parted hair and pragmatic demeanor, you glimpse his immense passion for artists and contemporary Ukrainian art.

Finally, in 2024, The Ukrainain House started preparing the expansive exhibition in conjunction with Sosnov and Lysun. The curators refer to the project jokingly as “our baby—our family business.” Lysun, who is tall and poised, smiles often as she recalls the ups and downs of organising a major retrospective. Sitting around their kitchen table, in an apartment not dissimilar to Glyadyelov’s, the couple’s collection hangs on all the walls, paintings by Pavlo Makov, a lithography by Joan Miro, and, among many, many others, photographs by Vladyslav Krasnoshchok.

Though just recently opened, the exhibition has generated a huge and overwhelmingly positive reaction from the public, made up of all different generations. It’s not uncommon for people to recognise themselves in Glyadyelov’s photographs, sometimes printed over one meter wide. “Yesterday, I was giving a tour for my parents. My father was trying to find himself in the room covering the Orange Revolution. He was looking at all the faces,” says Lysun enthusiastically.

The real challenge, say Lysun and Sosnov, was organising an exhibition in the middle of a war. Lysun touches on one example, “many men are currently mobilized. We couldn’t find a team to construct the walls. Only after our fifth attempt did we find a team capable of building them.”

And yet, like Glyadyelov, the project came to life through the participation of friends. Sosnov explains it like this: “In a certain sense, Ukraine is a homeland of volunteers.”

“Where would we be today?”: Glyadyelov’s exhibition reflects on Ukraine’s past

While preparing for the installation, as they placed Glyadyelov’s photographs side by side, new meanings appeared. The room depicting Ukraine during the 1990s, drunks asleep on the floor and children huffing glue, for example, shaped a new understanding: “Where would we be today if we had stuck with Russia?” says Lysun forcefully. Both believe the exhibit enables Ukrainians to recontextualize themselves. “It’s a project about timing,” say Lysun and Sosnov, who, together with French scenographer Igor Ouvaroff, had this specifically in mind during the planning.

The audience circling the Ukrainian House are Ukrainian themselves, living in the midst of 2025. All of them have seen the walls of a shelter, some have children fighting on the frontlines, and many know death on a scale other Europeans could not fathom.

All three, Glyadyelov, Lysun, and Sosnov, report that some visitors can’t get through the exhibition in one go. They have to leave, pause, maybe smoke a cigarette, or come back to finish the visit the next day. “Actually, most visitors witnessed what you see on the wall, even if they weren’t physically there. They probably remember each of these moments,” adds Sosnov, who decided with Lysun to include a disclaimer: This section of the exhibition presents photos depicting exhumations. If this topic is sensitive for you, please take care of your mental health and feel free to proceed to the next part of the exhibition.

While wanting to be soft with the viewers and not “retraumatize,” Lysun and Sosnov worked to keep a balance and not protect the viewer either. It becomes clear how risky putting on the exhibition actually was, “we were scared nobody would come,” admits Lysun, “because they might not want to see these things again.”

As Ukrainians themselves, the two curators' stated goal was to reveal where Ukrainian resilience comes from: “Because in the Western world—in the States, in Europe—they were saying Kyiv would fall in three days,” explains Sosnov.

Expansively, and a common theme throughout is Ukraine’s relationship to protest; photographs depict the 90s “Day of Earth” protests, led by the movement RUCK, up to the drastic amplification that was the Revolution of Dignity almost 20 years later. Glyadyelov remembers the night the Revolution started, November 21, 2013. He was walking back from a night with friends and saw “kids start to riot.” He went home, changed clothes, filled his pockets with film, “And then it was like a wheel. Till the last days of fighting.”

A horizontal Ukraine rising above the Russian hierarchy

“There is a saying in Ukraine, it will take a husband 10 years to fix the toilet, but 15 minutes to build a barricade.” Glyadyelov laughs as he pours out another glass of wine. In his opinion, Ukraine works on a horizontal level, far from the vertical hierarchy that the Russians tried so hard to impose on the country.

This understanding cemented Glyadyelov’s belief, since the middle of the 90s, that “there will come a big war. I understood the kind of war it would be.”

During the Russian invasion of Kyiv, Glyadyelov stayed in the city. As people were fleeing the surrounding neighbourhoods of Irpin and Bucha, he remembers civilians talking to him as he photographed them, “They would say ‘Slava Ukraini,’ you could see how important that moment was for them, just to say it,” remembers Glyadyelov.

When Kyiv was liberated, he visited Irpin and Butcha again and again, both sites where Russian atrocities took place, documenting the mass graves they left behind.

“Day by day, I was in these places documenting what was happening,” says Glyadyelov. He went to Hostomel, Borodianka, Makariv, and many other villages and towns in the region. Every evening, Glyadyelov would come home to Kyiv and recount to his neighbors what he had seen. They’d be sitting around the table, drinking coffee, tea, sometimes brandy. “It wasn’t a ritual—at the time it was just part of everyday life,” he says.

Taking us up to the third floor, he stands in the exact place where he had documented the scene three years ago—a woman bringing him over a stool by candlelight, and a small group huddled around a table in the building’s hall.

Like many photographers, you could qualify Glyadyelov as obsessive. When asked if he thought about the future, he simply answered, “Of course, I think of how long I have to make my pictures.”

In his apartment’s darkroom, he sometimes spends 24 hours printing. “There’s a white piece of paper, and then you see the picture. It’s a kind of magic,” he says as he opens the cupboards and blue binders packed around him. As a young student, he would go to the library and leaf through the legendary American publication Life, page after page, after page, he recalls.

At a party in his apartment, after our interview; young curators, artists, and photographers sit on the floor, or huddle together on the couch. Glyadyelov goes through his PDFs with a friend in the corner, essentially Glyadyelov’s digital archive; the list on the computer is sorted by year: 1996, 1997, 1998, and so on. Scrolling and scrolling, he stops on pictures he took when he used to go mountaineering in the Pamir Mountains, two cameras on his hip, one black and white, one colour.

For Glyadyelov, this question of archiving arises more and more frequently, not only because of the war but also because of the negatives' potent importance as historical records. Glyadyelov explains that now he’s moving to negative filing boxes to preserve the negatives from dust and is even considering Sosnov’s suggestion to purchase some kind of inflammable lockbox.

Glyadyelov is steadily preparing for this phase, though when asked if he is an organized person, he repeatedly answers, “no.” It seems he just has never had the time, not one to stop and catch his breath.

Like the visitors, who often space out their visit to “And I Saw,” Sosnov and Lysun often brought up the necessity of breath, how they purposely paced and spaced the exhibit so as not to overwhelm. Glyadyelov, on the other hand, breathes through the act of photographing itself. Up in the mountains as a young man, working with Médecins Sans Frontières in Sudan, three months on the Maidan Square in the freezing winter, covering Donbas in 2014, Glyadelov has never stopped, and in doing so has exhaled Ukraine’s archive into being.

-6c7b568bf1f65853b7afd9dc1c3ca1fe.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)