- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Amid a War Full of Phone and Drone Footage, Ukraine’s Babylon 13 Makes Cinema

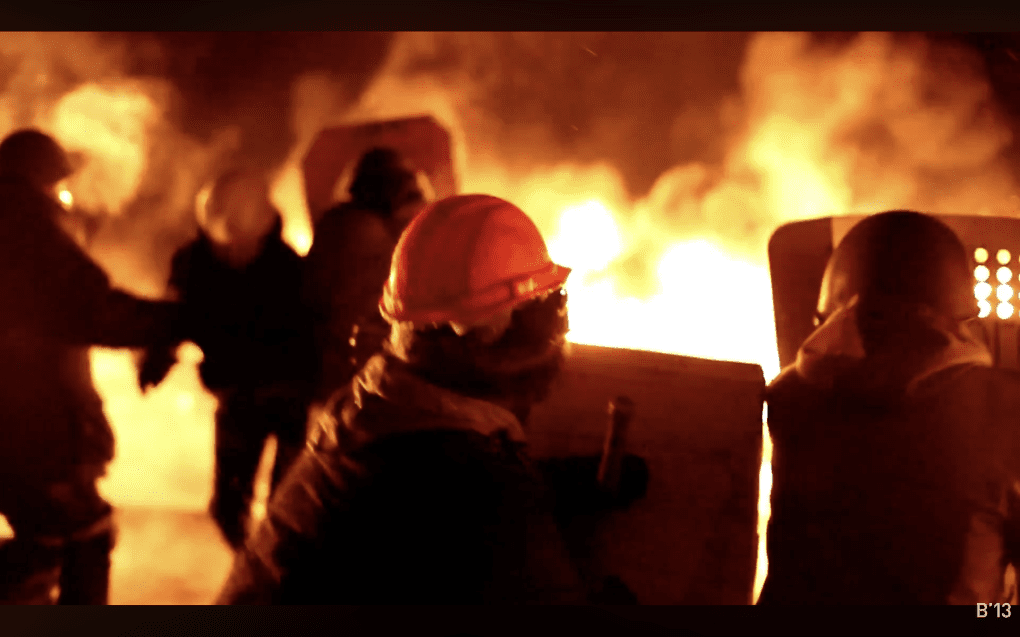

Born amid the street clashes on Kyiv’s Independence Square in 2013, the Ukrainian documentary collective Babylon 13 has spent more than a decade filming the country’s resistance—from the Revolution of Dignity to Russia’s full-scale invasion. What began as rapid, anonymous shorts shot on the barricades has evolved into one of Ukraine’s most extensive cinematic archives.

Faced with a constant flow of images depicting the war and its consequences, how do Ukrainians manage to process reality and offer their compatriots—and the world—a structured and reflective understanding of the events Ukraine has experienced, from the Maidan Revolution of 2013–2014 to the fourth year of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine?

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine appears to be the most filmed war in history. These images serve as proof of combat, evidence of war crimes, and tools to counter Russian disinformation. But they also form the basis for a broader reflection on Ukrainian identity—its evolution and its place in the world.

This is the footage of the russian Shahed drone attacking an oil mill belonging to the American company Bunge.

— Oleksiy Goncharenko (@GoncharenkoUa) January 5, 2026

As the result, more than 300 tons of oil was spilled, causing serious damage to the mill and environment. pic.twitter.com/JflSn2NkBd

Since 2013, the community of filmmakers known as Babylon 13 has become one of the most dynamic examples of this effort. With hundreds of short films and dozens of feature-length films released on YouTube, screened at festivals, and shown in cinemas in Ukraine and around the world, Babylon 13 has, for 12 years, accompanied and extended the Revolution of Dignity through cinema.

The Revolution of Dignity was also a documentary film revolution

In November 2013, following a sudden decision—rejected by the vast majority of the population—made by then-president of Ukraine Viktor Yanukovych to withdraw from the EU Association Agreement and move Ukraine closer to Russia, thousands of people gathered at Independence Square in Kyiv. This marked the beginning of what the world came to know as Euromaidan, and what Ukrainians call the Revolution of Dignity.

Denys Vorontsov, Volodymyr Tykhyi, Ivan Sautkin, Maryna Vroda, and other filmmakers from the fiction world sensed that something historic was unfolding—and that a new method was needed to support the protests.

“There were six of us who shot small interviews, and already that night we edited it in Ivan Sautkin’s workshop,” said Volodymyr Tykhyi, director and co-founder of Babylon 13.

They picked up cameras, filmed the first day of protests, edited the footage, handled post-production, subtitled it in English, and released the film anonymously on YouTube—all in less than 24 hours. This mode of production would remain one of their defining trademarks.

Fewer people were throwing Molotov cocktails than people filming those who were throwing them.

Volodymyr Tykhyi

Film director / Co-founder of Babylon 13

Inside Kyiv’s Cinema House, which they chose as their base, the group picked a name: Babylon 13—taken from the Wi-Fi password of the Babylon bar located there, itself named after Babylon XX, the cult film by Ukrainian director Ivan Mykolaichuk. One month later, the collective had grown to around 50 members. Filmmakers were joined by students, accountants, and IT specialists, all gathering despite the serious risks to their safety.

Censorship affected all national media outlets, with journalists particularly targeted by repression under then-President Viktor Yanukovych’s administration. The Babylonians took risks that no foreign filmmakers were taking at the time because they were both actors in and witnesses to the unfolding revolution. As Volodymyr Tikhyi says, foreign correspondents, often based in Russia, struggled to grasp the situation and filtered events through the prism of Moscow.

“They perceived everything through the lens of events that had happened in Moscow one and a half or two years earlier. And we didn’t like that. Who could like that?” Tykhyi said.

The internet became the only space of media freedom that the authorities could not control. But Babylon 13 was not there to inform—it was there to strike emotions. Even when they lasted less than a minute, their films were conceived as collective works of cinema.

“From the beginning, we were not filming the events themselves, but the consequences of those events,” Tykhyi explained. “They were operational reflections, small in form, but they allowed the protesters themselves to understand what they were doing differently.”

Without reflection, he argued, historical moments are erased by time. He believes their approach helped Euromaidan protesters grasp the importance of what they were doing.

“We had a concrete goal—to change Yanukovych’s regime,” Tykhyi said.

Documenting the invasion

After the revolution’s victory in February 2014—following over a hundred protesters killed by regime forces and Yanukovych’s flight to Moscow—Russia did not stop there.

“Russia had prepared a kind of plan A/B in case the revolution succeeded,” said Volodymyr Tykhyi. Indeed, Moscow sent troops to Crimea to pressure a false referendum aimed at attaching the Ukrainian peninsula to Russia.

Babylon 13’s mission became broader: to fight Russia and its ideology through cinema. The events that followed left them no respite. “There wasn’t even a sense that we could breathe,” Tykhyi said.

Two filmmakers from Babylon 13 went to Crimea as early as March 2014. “And we got them out almost by a miracle,” Tykhyi said, recalling that other Ukrainian journalists and filmmakers—such as Oleh Sentsov—were less fortunate and were imprisoned by Russia.

Soon after, Russian-backed forces in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions initiated a hybrid campaign against Ukraine, combining conventional military tactics with irregular warfare and disinformation. Babylon 13 became, by force of circumstances, a producer of “war films.”

For Tykhyi, filming the war came naturally. Many Maidan protesters volunteered to defend their country from the Russian invasion, and because Babylon 13 had filmed them during the revolution, they readily allowed the filmmakers to document them during combat.

You live with them in basements or buildings where the enemy position is literally 200 meters away. Back then, everything was very democratic.

Volodymyr Tykhyi

Film director / Co-founder of Babylon 13

The Babylonians became inventive in drawing attention—both in Ukraine and abroad—to the war and its consequences. In 2015, they released War Note, composed exclusively of videos filmed by soldiers themselves.

They also began traveling extensively—especially across Europe and the United States—screening their films wherever possible, from Ukrainian diaspora associations to festivals. They even devised unconventional outreach strategies, including promoting their films on Facebook to users frequenting fast-food locations near US military bases.

“When you can target advertising directly—for example, at military bases in the United States—no one will tell you how to get onto the base. But every base has a Burger King,” Tykhyi said. “A soldier walks into Burger King, opens Facebook, and sees an offer to watch a film about the war in Ukraine.”

We bring you stories from the ground. Your support keeps our team in the field.

At the same time, they began producing feature-length films with credited authors, including Volodymyr Tykhyi, Kostiantyn Kliatskin, and Ivan Sautkin.

They also became a model for a generation of filmmakers growing up in independent Ukraine, embracing the documentary format. New production companies, such as TABOR, emerged, eventually influenced by the Babylon 13 model to their own visions and projects.

The full-scale invasion turned every filmmaker into a war actor

Until February 24, 2022, only a few intelligence agencies warned of an imminent Russian invasion. In Ukraine, even though the threat was felt more strongly than elsewhere, not everyone expected the intensity of the invasion.

“We were ready, we expected it, but until the very last moment, we couldn’t believe it would be this massive,” Tykhyi said.

On February 25, Babylon 13 released its first video compiled from amateur footage collected from social media: “Ukraine, stay strong. But this is not only about Ukraine. It is a threat to the entire civilized world. Wherever you are—go to demonstrations. Push your governments to act.”

For the collective, the first days of the full-scale war were dedicated to organization. As Russian troops encircled Kyiv, Babylon 13 created a group called Babylon’s Sirens to track members’ safety in real time and coordinate actions.

Some Babylonians moved to Lviv, farther from Russian attacks. Others stayed in Kyiv, but strict curfews and early chaos limited their ability to film. A third group—especially those with experience using drones in cinema—joined the fighting. They fought and filmed, filmed and fought. The line between “filmmaker” and “soldier” began to blur.

Babylon 13 actively used private videos posted by Ukrainians themselves, especially on TikTok. “We went through a period of working mainly with footage shot by others,” Tykhyi said, “At the same time, we filmed evacuation stories and military units wherever we could reach.”

All topics were covered—from the training of territorial defense volunteers to animal rescue patrols, and even icon painter Lev Skop, who sent his works to army brigades.

Their first feature film about the full-scale invasion, One Day in Ukraine, followed their founding principle: not to deliver information, but to make cinema. Shot in a single day—March 14, 2022—it showed an entire country mobilized for war and humanitarian effort just 20 days after the invasion began.

The film was produced in just a few weeks and quickly screened at international festivals, including Sheffield Doc/Fest 2022 (UK), Kaohsiung International Film Festival 2022 (Taiwan), and Warsaw International Film Festival 2022.

Another example of the Babylonians’ creative force is Fortress Mariupol (directed by Yuliia Hontaruk), a documentary series built from video calls with the soldiers trapped inside the Azovstal steel plant .

“Finding foreign partners is becoming increasingly difficult,” said producer Ivanna Khitsinska. “Ukraine is fading from the global agenda. Many foreigners say they are ‘tired of war stories.’ We must find new ways to tell our stories.”

Babylon 13 is a democratic organization, she continued: “It is sometimes harder to manage than an authoritarian structure, because no one gives orders. As a producer, I must convince others that my idea is interesting—and filmmakers must convince us of their projects. It’s a more honest process.”

Khitsinska, who also directed the VR short Shelter, is now producing a new Babylon 13 film, DNA of a Nation, directed by Ivan Sautkin.

A living archive of independent Ukraine

Babylon 13’s films have become one of the monuments of Ukraine’s independent history—almost a national archive. Nearly 700 films produced since November 2013 trace Ukraine’s path toward defending and defining its independence, the formation of its inclusive and dynamic identity, in contrast to the folkloric monolith Moscow seeks to impose.

“We have produced 14 feature films and more than 600 short films. Our YouTube channel has become a national archive of Ukrainian resistance,” Khitsinska said.

The full-scale war has created immense difficulties for artists—especially filmmakers, whose image-making skills are now crucial in a drone-dominated battlefield.

Today, almost all the men in the collective are mobilized. They film when they can, but it is often operational footage to raise funds for drones rather than creative documentary filmmaking.

Volodymyr Tykhyi

Film director / Co-founder of Babylon 13

Denys Vorontsov exemplifies this reality. A first assistant director by profession—he worked on Pamfir, selected at Cannes in 2023—he picked up a camera at the start of the invasion. After filming extensively in Kharkiv, he continued directing until volunteering to join the armed forces in 2024. His upcoming film, The Schoolmates, follows three Kharkiv photographers caught between war and their desire to continue living as documentary artists.

“Completely different people make films here, in completely different styles, with completely different perspectives,” said Ivan Sautkin. “That is our value. Nothing is imposed. This is a living creative collective.”

Sautkin’s next film is not directly about the war, even though war dominates everyday life in Ukraine. DNA of a Nation is a collective portrait of Ukraine and Ukrainians—told through humor, self-irony, and the figure of poet Taras Shevchenko.

People know Ukraine has corruption. They know boxer Usyk and footballer Shevchenko. But Europe and the world do not know Ukraine’s unique national character.

Ivan Sautkin

Film director / Co-founder of Babylon 13

“In Shevchenko’s poetry, continued Sautkin, are embedded all the core principles of the Ukrainian nation: resistance to Russian imperialism, love of the homeland, and, of course, the global aspiration for freedom.”

-7f54d6f9a1e9b10de9b3e7ee663a18d9.png)

-24deccd511006ba79cfc4d798c6c2ef5.jpeg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)