- Category

- Culture

War Veterans in Ukraine Bring Their Stories to the National Stage

Ukrainian veterans are taking to the stage with the Theatre of Veterans and retelling their experiences, reclaiming control of narratives often written without them. Many have sustained life-altering injuries, from amputations to severe burns, and now translate those realities into physical performance. Directed by professionals but shaped by the veterans themselves, the productions are raw, immediate, and cathartic.

In Kyiv, a theater company, Theater of Veterans, led by and for veterans, is transforming personal trauma into live performance, shifting war stories from the trenches to black-box theaters.

“The courage of these people—the second courage after the war, the courage to go on stage—is a hope for our society,” said playwright Maksym Kurochkin, a veteran and Educational Program Lead at the Theater of Veterans, created within TRO Media (the Communications Department of the Command of the Territorial Defense Forces of Ukraine). “We can accept this kind of art, enjoy it, and live in this new reality, where people like us do not look away, but look with gratitude” he said when we met at the company’s rehearsal space in Kyiv, where he sat in the break room between rehearsals.

A professional playwright, Kurochkin has a graying beard, and isn’t afraid to swear.

He explains: “When words like ‘fuck’ and ‘shit’ are spoken on stage, when there is profanity, it is because writing about war requires telling the truth.” Kurochkin says unvarnished, documentary rigor is “one of the core principles” of the theater’s work, aiming to reflect “how people actually speak,” a choice that can surprise Ukrainian audiences expecting a more polished performance.

And, he adds: “Therapy is, roughly speaking, a side effect.” Beyond rehabilitation, the Theater teaches soldiers the basics of dramaturgy—how to write plays.

Veterans reclaim movement on stage

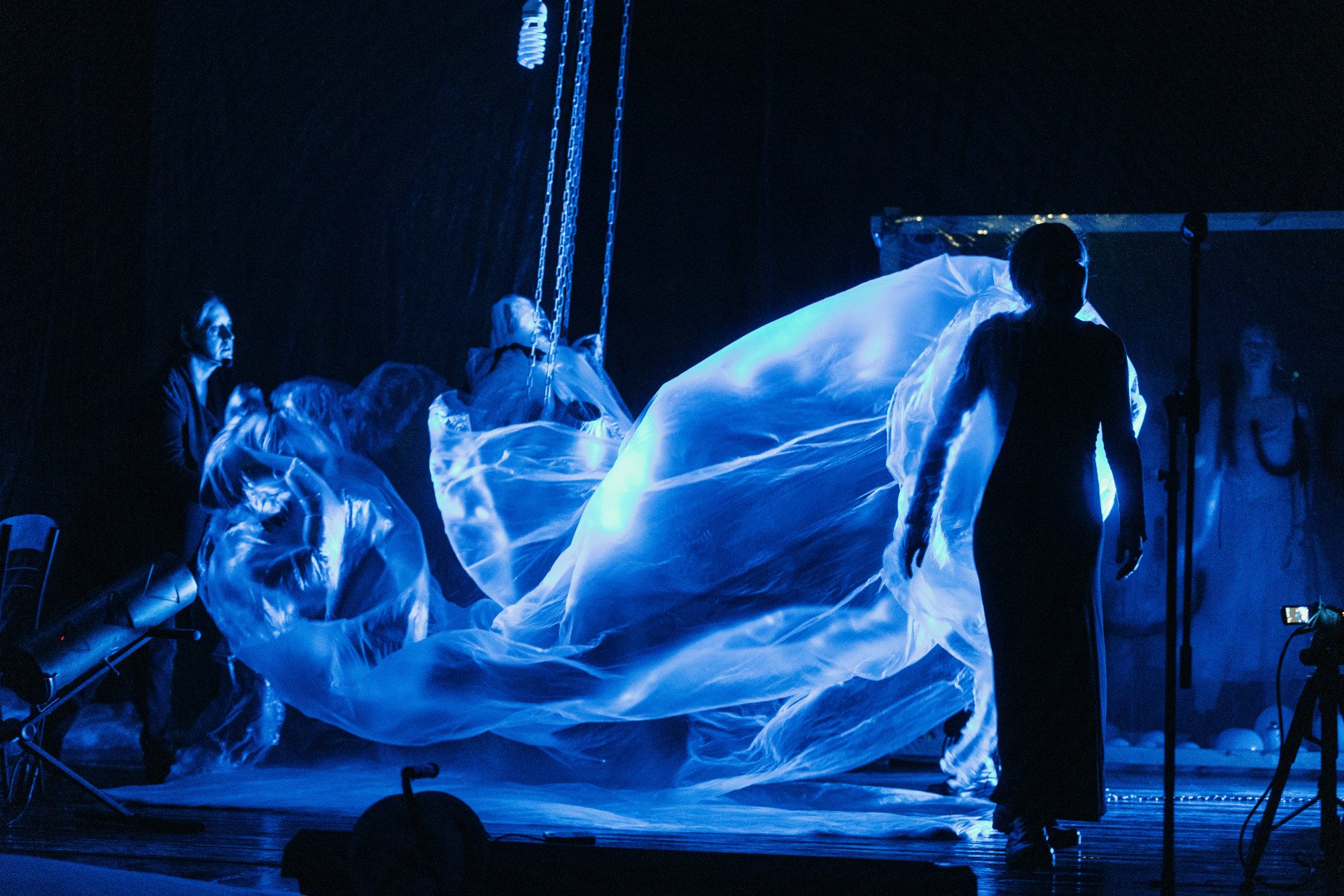

This was on full display in the theater company’s latest play, Eneida, which brings veterans onto the stage, taking cues from Ivan Kotlyarevsky’s literary classic but speaking in the language of physical and performative theater.

Kotlyarevsky’s poem, a burlesque reworking of Virgil in which Trojan heroes become Zaporozhian Cossacks, has a lot of movement in this interpretation directed by Olha Semoshkina, the chief choreographer of Kyiv’s Franko Theater. Kurochkin said this part took the longest to prepare because many participants were severely injured in Russia’s war against Ukraine, with some veterans’ wounds limiting their ability to perform physical theater.

While Maksym Kurochkin leads the Educational Course for Veterans: the program in which former service members learn to write dramatic texts — the Theater of Veterans is overseen by its artistic director, Akhtem Seitablaiev, a veteran, actor and director, and an Honored Artist of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

Seitablaiev, whom we did not meet, reportadly described the early phase of rehearsals as follows: “For the first month, the veterans we worked with were simply learning how to fall correctly.”

One of the actors, Yehor Babenko, sustained full-body burns in 2022 and lost half his hands. He plays the lead role of Aeneas in the production “Eneida,” and greets us at a veterans hub on Kyiv’s right bank. It’s filled with books, drawings, and a big drum set. When we sit down to talk, he explains that when he was young, he felt “very insecure.”

“It sounds ironic, but after my injury, I became more confident,” he says.

Acting had a significant impact on Babenko: “The rehearsal process helped me understand that even though I had been injured, I could still move, still express something. Psychologically, if you compare how people were when they first arrived and how they are now, the progress is very noticeable.”

Self-discovery through drama and myth

As part of the first acting exercise for veterans, Kurochkin begins with film analysis: “We begin with analyzing a film by Fritz Lang, referring to the two-part silent epic Die Nibelungen—Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge. The choice is deliberate. The film’s themes—revenge, loss, and the weight of myth—offer a powerful starting point for veterans learning to process their own narratives on stage.

Without focusing solely on therapy, as Kurochkin noted, the Theater of Veterans seems to achieve therapeutic results. Since Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, about 1.5 million people have gained veteran status.

The word “veteran” often implies someone who has completed their service and left the front. But in Ukraine, and by definition, it is a formal legal status that acknowledges military service. “I’m still serving, but I have veteran status,” Kurochkin said, using himself as an example. It doesn’t guarantee that someone is done with the war. Many veterans, if still eligible and fit, can be called back into service.

“When someone returns from the front to Kyiv or any other city, it’s a cultural shock for them,” Kurochkin says, adding that parties, social events, and everyday life can feel uncomfortable for returning service members, because they’ve grown used to something entirely different.

“The worst thing you can do is stay home and isolate yourself, thinking that you’ve changed and no longer belong,” says Babenko. “Your body may have changed. But that doesn’t mean people don’t still see you as a person.”

A veteran’s raw performance—the theater’s emotional breakthrough

Before long, one veteran’s raw performance would give the theater its emotional breakthrough. When Hennadii, a soldier in Ukraine’s Special Operations Forces, was first invited to perform the play he had written, it marked a turning point for the entire theater project.

“We asked him to appear as an actor,” one organizer recalled. “That was a decisive moment. If it had gone badly, the whole idea could have collapsed.” Hennadii, who lost a leg in the war, had written a raw, personal script about confronting that loss—arguing with his missing limb, giving it voice on stage.

His performance, delivered with unfiltered emotion, deeply moved those present. “The way Hennadii delivered his text changed people. We saw emotions that mattered.”

Theater leadership had been waiting to see real impact, and they found it in him. His personal story is just as striking: originally from Donetsk, Hennadii was once part of an organized criminal group before moving to Kyiv and enlisting after the full-scale invasion. Reflecting on his journey after the premiere of his play, he sent a message to one of the theater’s founders: “For the first time in my life, I like myself.”

How Soviet structure bridled personal voice

For Semoshkina, director of Eneida, one of the central challenges in working with veterans was guiding non-professional performers through deeply personal material without losing their individuality. “The hardest part was preserving individuality throughout the process—and keeping a truly personal approach to every scene, to every person,” she said.

When asked, Kurochkin also reveals how the theater managed to get soldiers to write honestly, without strict adherence to form or convention. “The idea that you should write the way you want is quite revolutionary,” he says, adding that much of the work focuses not on technique, but on breaking internal barriers. “Everyone has this feeling in their head that there are models you must imitate.” To get the soldiers to open up, Kurochkin uses honesty as a central tool.

I tell the truth about myself.

Maksym Kurochkin

Veteran and Educational Program Lead at the Theater of Veterans

The same standard is used when assessing a veteran’s work: “no one will call a shitty text ‘well done,’” says Kurochkin, “That is one of our principles.”

The Soviet form, which most Ukrainians are used to, also inhibits the writing. “Soviet theater was entirely embedded in the ideological structure. It served ideology,” Kurochkin says. There was only one dominant acting technique—derived from Stanislavski . Though evolutionary for its time, it permeated everything, mutating slowly into socialist realism. “Ukrainian society is still very traditional and regulated,” he says.

Facing reality head on

War-related plays or works by servicemen make up just 5-10% of major national theater repertoires in Ukraine. “That’s already a problem at the level of basic culture,” Kurochkin says, noting that traditional theaters often cater to audiences seeking light entertainment. “Theater of Veterans is about truth—about what’s happening right now. Not everyone is ready for that.”

Though increasingly, theatergoers are embracing this style of storytelling, grounded in everyday language rather than formal convention, it also creates a shared space for rehabilitation. As the audience is also navigating its own recovery

“We don’t give diplomas saying you’ve been healed,” says Kurochkin. “That’s not what this is. What we give them is a profession.”

-457ad7ae19a951ebdca94e9b6bf6309d.png)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)