- Category

- Culture

Who Were the Cossacks in Ukrainian History?

Were the Cossacks Ukrainian or Russian? The answer’s simpler than it sounds. The Cossacks were born in the flatlands of what is now southern Ukraine, where they carved out a fierce, democratic society that became a cornerstone of Ukraine’s—and Europe’s—unfinished struggle for freedom from empire.

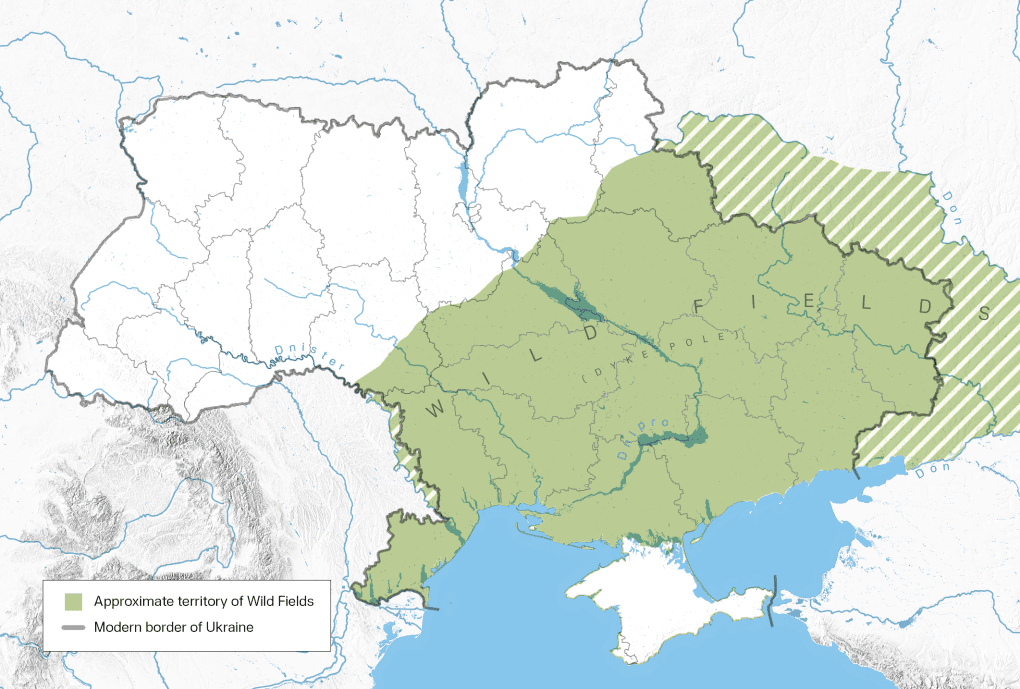

The Ukrainian Cossacks didn’t appear in a vacuum. Forged in the chaos of competing kingdoms, they emerged from the Wild Fields of the Dnipro. Slavic peasants, runaway serfs, burghers , lesser nobility, and even Tatars, Greeks, and Jews gathered in a borderland where no empire’s law reached. These people built fortified camps called Siches, elected their leaders, and created a society where power came from consent, not bloodlines.

The Ukrainian Cossacks became part of a cosmopolitan world, descending from the same warriors who once sailed the Dnipro with the Vikings, trading from Kyiv to Byzantium.

Who were the Cossacks

The Turkic word Qazaq, which means “free man" or “wanderer," originally described people who lived on the edges of settled states—free from serfdom, military service, or direct rule.

By the 1500s, the Ukrainian Kozak—Cossack emerged, becoming a symbol of defiance and a serious political force. These were people who didn’t just want freedom from a landlord, but who imagined a different political order entirely. British historian Arnold J. Toynbee later wrote that the scattered Cossack hosts from the Don to the Ussuri all traced back to the brotherhoods formed along the Dnipro—a root that carried the idea of self-government across Eurasia.

The Ukrainian Cossacks were a major defensive force in the 16th and 17th centuries, guarding the volatile frontier. Positioned between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Muscovy, and the Crimean Khanate, they fought to protect local communities across one of Eastern Europe’s most contested regions.

The Cossacks were both warriors and pragmatic statesmen. Nothing proves this better than Hetman Ivan Mazepa’s alliance with Sweden’s Charles XII during the Great Northern War in the early 1700s. From the time of Kyivan Rus , Ukrainian lands had been connected to Scandinavia through trade, as well as political and cultural exchange. The Dnipro was once part of the “route from the Varangians to the Greeks,” a highway of commerce and ideas that tied Kyiv to Stockholm as much as it did to Constantinople.

The alliance was part of a longer, underacknowledged arc of Ukrainian history: moments when Ukraine looked north and west for alternatives to imperial domination. Mazepa’s move was a calculated bid to secure independence from the Tsardom of Moscow by joining forces with one of Europe’s strongest armies. He understood that to break free from the empire, Ukraine needed not only swords but connections.

Zaporozhian Sich, Magdeburg law, and early autonomy

The Zaporozhian Sich, founded in the 1550s, was a functioning republic where the Sich Rada elected the Hetman , passed laws, and ruled by consensus. It was here that Bohdan Khmelnytsky launched the 1648 uprising, uniting peasants and Cossacks into a force that birthed the Cossack Hetmanate — Ukraine’s first modern state with its diplomacy and borders.

But Ukrainian political sophistication didn’t end on the steppe—the vast frontier where the Cossack hosts ruled, rode, and negotiated their autonomy. Political life was grounded in the Magdeburg Law—a system of municipal self-government adopted across Central and Eastern Europe, including much of Ukraine, that allowed towns to elect their officials, run courts, and regulate trade. It became a striking contrast to both feudal hierarchy and imperial command.

In cities like Kyiv, Chernihiv, and Vinnytsia, the Law governed urban life for centuries before Russian centralization swept it away. This system was a European civic mindset that enshrined self-government, elected councils, and independent courts. The Cossack world wasn’t chaotic, as many may think—it was layered. The law provided something the Cossacks valued: order without submission, structuring towns while regimental councils governed the steppe.

What did the Cossacks look like?

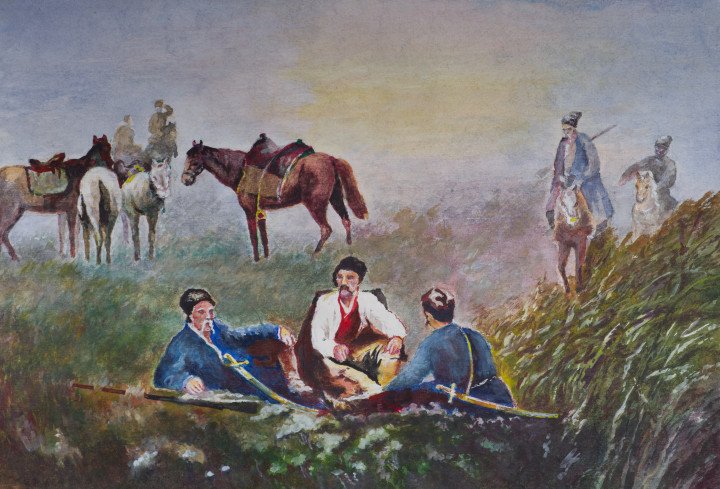

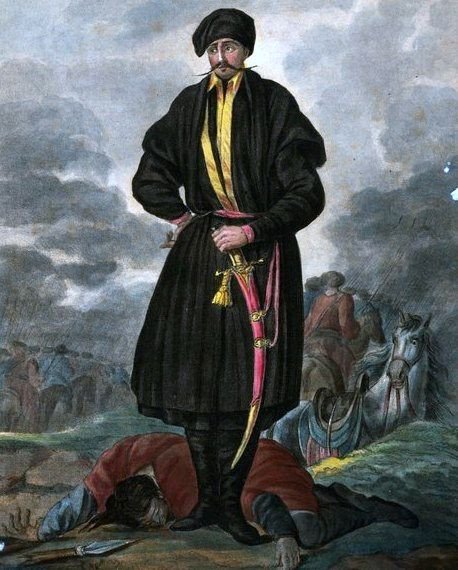

The Cossack warrior became an icon recognized from Stockholm to Istanbul: a shaved head with an oseledets forelock, thick mustache, embroidered sash, cross on the chest, and saber on the hip. Their weapons matched their ambition: curved shashkas, pistols, and the bulawa — the Hetman’s ceremonial mace.

But their image was only part of the story. From the 1500s on, Ukrainian Cossacks defended the southern frontier and raided deep into Ottoman lands with their fast chaiky boats. They burned ports and stormed ships, reaching the gates of Istanbul itself.

In folk songs, the Cossacks were praised as “falcons on horseback,” “sons of the steppe,” and “defenders of the faith,” depicting them as wild but righteous, chaotic but brave. They had a sharp sense of humor, too, often giving each other ironic nicknames: a towering warrior might be called “Shorty,” while a smaller one was dubbed “Giant.” When the Ottoman Sultan once demanded their surrender, the Cossacks famously replied with a letter so obscene, defiant, and gleefully vulgar that it became legendary across Europe.

The moment was later immortalized (or at least wildly imagined) by Ilya Ripin in his painting Reply of the Zaporozhzhian Cossacks, where a circle of swaggering, roaring warriors draft their profane response with infectious delight. Whether the letter was ever truly sent remains uncertain, but the spirit of the reply was unmistakably Cossack.

Do Cossacks still exist?

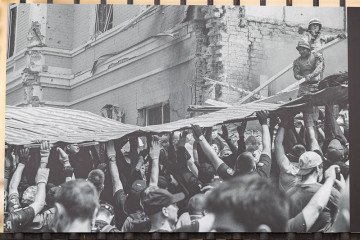

No more warrior republics or Siches stand today. But the Cossack legacy Ukraine inherited is alive in traditions, symbols, and a sense of identity. From Kostiantynivka to Zaporizhzhia, modern Ukrainian Cossacks keep these customs alive in reenactments and cultural organizations.

The Ukrainian Cossack—saber raised, forelock flying—still symbolizes freedom and defiance, emblazoned on military patches and echoed in schoolbooks. In today’s war-torn landscape, the Cossack story is more than folklore. It’s a reminder that Ukraine’s struggle for sovereignty is part of a European fight for self-rule stretching back centuries.

Cover image: Ukrainian Cossack piloting an FPV drone by Sestry Feldman (Source: Getty Images)

-85339c7a2471296aa16e967758e245c6.png)