- Category

- Culture

Life Near Ukraine’s Frontline in the Early Years of Russia’s War, Captured by Anastasia Taylor-Lind

Families in the East of Ukraine lived through a war long before Russia’s 2022 invasion. In 5k from the Frontline, a digital platform and short film, British-Swedish photojournalist Anastasia Taylor-Lind and Donetsk native Alisa Sopova captured the everyday lives of civilians in towns like Avdiivka and Toretsk before the Russian army wiped them off the map.

The concept of the “frontline” in Ukraine is shifting. Today, it’s often referred to as a “kill zone”—a 30-kilometer bubble saturated with deadly first-person view drones. But before Russia’s full-scale invasion, it was different. Anastasia Taylor-Lind and Alisa Sopova have been documenting this evolving frontline since 2014.

“When we started, we always had to explain to people that there is a war in Ukraine,” says Taylor-Lind. The toll of Russian attacks on civilians living in the area, those who, from today’s perspective, knew the war before the full-scale war, was not widely covered at the time.

The idea, Sopova says, that there are no “normal” people in a war zone was extremely widespread, both abroad and inside Ukraine. 5k from the Frontline is an attempt to answer such questions through the portrayal of family and relatives coexisting within a context once unimaginable to those portrayed.

In resisting the temptation of the “breaking news” story, the two reporters remember “At the time, Donbas was seen as a frontline, but a very slow one.”

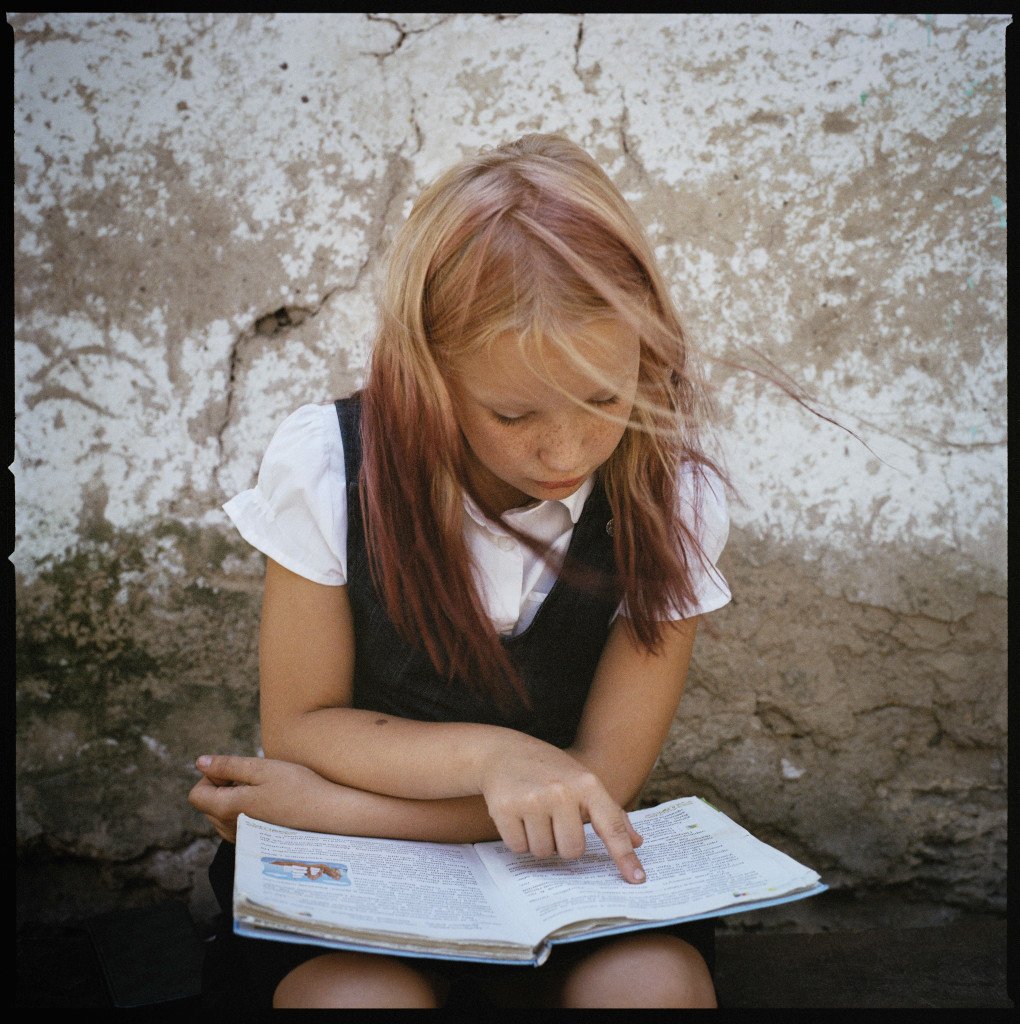

The launch of their short film, as well as the website 5k from the Frontline—more of a digital journey—breathes life into their project. Taylor-Lind’s photographs, mostly taken on a medium-format Hasselblad, and her videos, paired with Sopova’s words unfold as you scroll down. Photographs and Stories of many Donetsk families, taken around 2018, such as the Hrynyk family from Avdiivka—are built from everyday moments: barbecues, caring for pets, and weddings.

When Avdiivka fell to Russian forces in 2023, this long record of the banal and the intimate took on a different weight, becoming a rare and singular document of a place and a way of life that no longer exists in the same form.

“I’ve spent twenty years working in war zones, listening to people say they never believed war could reach their town, their street, their home. No one really believes it until it happens,” emphasises Taylor-Lind.

Ultimately, the project emerges in defense of those who stay behind.

“I was in Crimea in 2010, but I really began reporting in Ukraine in 2014, at the very start of Maidan,” says Taylor-Lind. “I was on my way to Donetsk for a different story. I stopped in Kyiv to apply for a press pass, and while I was waiting for it, I started photographing in Maidan Square. I didn’t want to leave. I set up a makeshift portrait studio inside the barricades and made portraits of the men fighting the running street battles.”

2014 was the year Russia first invaded Ukraine. That summer, Taylor-Lind went to Donbas for the first time. There, she met Alisa.

“The point of our project was that what was happening in Ukraine was being described as a ‘frozen conflict’ or ‘Europe’s forgotten war,’” says Taylor-Lind. “The experiences of civilians in Donbas had slipped from the headlines. The project was very much about the people who chose to stay, even when millions had already fled.”

But the funding for it came only after Russia’s full-scale invasion. The National Geographic Society, the CatchLight Global Fellowship, and the Canon Female Photojournalist Award—all chipped in.

“The project was completely self-initiated and self-financed for the first five years,” says Taylor-Lind. “We’d go on a reporting trip, then package it up and pitch it to the New York Times, Time Magazine, NPR, The Guardian—all of whom published it in chapters, but it never all sat together. There are only about a hundred pictures on that website. That’s a small edit.”

We wanted to make it in English and Ukrainian so it would be accessible and free. Typically, photographers would make a photo book at this stage, but photo books are expensive and hard for people to get. It just felt inaccessible and not in the spirit of our project.

“5k from the Frontline, started in 2018,” says Taylor-Lind. Before working in Donbas, she covered Iraq, Afghanistan, Gaza, Libya and more. In 2013, Taylor-Lind spent three days in Jalalabad, photographing Afghanistan’s polio eradication campaign. Her resulting project, The Surge, captured vaccinators at work during wartime. “Before I met Alisa, I had that judgment—Why stay? Why not leave? I hadn’t experienced war destroying my city or my home. In my family, war is distant by a generation. My father was born at the end of World War II. My grandmother took him to the underground shelters during air raids. That history felt remote to me. Working in Donbas changed that.”

“It was my story,” says Sopova, explaining her commitment to “slow journalism.” “I was a civilian from there, and I saw a huge gap between what was happening and how it was being covered. I wanted to tell the story no one seemed to care about. I was living it, my family was living it.”

“Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, our reporting has been very different,” says Taylor-Lind. “I have a large edit of images just of Mira, her brother, and their parents. Mira is part of a big extended family, the Hrynyk family. We first met Olha and Mykola, her parents, when they were living about fifty meters from a Ukrainian frontline position in Avdiivka. Both Mira and Kyrylo were born after 2014. They have never known peace.”

Now the Hrynyk family lives in the Poltava region, where Kyrylo and Myroslava attend school. Mykola, along with all the men in the extended family, is serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. “They are all safe and well,” says Taylor-Lind when I ask her about them.

“My preference is to make pictures using a Hasselblad and film,” says Taylor-Lind. “You hold a Hasselblad at waist level, so you never cover your face when photographing someone. You can maintain eye contact, and the process feels less intimidating.”

Another reason to use it—the square shape. “A square frame is easier for me to compose than a 35mm rectangle,” she says. “And with film, I only have 12 frames on a roll. That forces a different pace. I might spend hours looking through the viewfinder, but I’m not pressing the shutter very often.”

“I remember when Instagram Stories arrived,” she adds. “It’s only relatively recently that the Instagram grid itself shifted from square to a portrait format.”

In the short documentary 5k from the Frontline, the split-screen idea came from Paolina Stefani, the director and editor of the film. When Taylor-Lind sent her entire iPhone archive from the past seven years, Stefani spent weeks going through it. The vertical videos turned out to be perfect for split screen, and played seamlessly into the narrative Taylor-Lind and Sopova had explored.

Now it feels as if the way Taylor-Lind films becomes a record of time itself—from before Instagram Stories reshaped visual habits to the present. “That approach is striking,” she says, “Especially toward the end, where the split screen conveys distance and simultaneity—different things happening at once, thoughts and events misaligned.”

It was Sopova who wrote the voiceover. “Her writing, her voice, and her story,” says Taylor-Lind. “She talks about me and my life—and mentions that she grew up in Donetsk. I’m introduced as a character about halfway through.” Alisa, who is from the very communities they documented, has known these places her entire life.

“In Krasnohorivka, people lived without heating since 2014, burning furniture to survive, but international media ignored it,” says Sopova. “And Ukrainian media would overwhelmingly focus on the army.”

Working as a fixer taught her a lot. “Most journalists would get close to destroyed places, but then they were in a hurry to leave. The people who were always ready to host us, like soldiers or civilians, were left behind. I wanted to stay, drink their wine, eat their pickles—not abandon them at the most sensitive moment.”

Foreign outlets covering Ukraine are especially important now. “Ukraine depends so much on international support,” says Sopova. “When foreign newspapers report on the war, people talk about Ukraine. That attention really matters.”

Despite this, Sopova saw the ugly side of frontline journalism. “Journalists would try to get as close as possible to the most destroyed places. But once they got there, they were scared, stressed, and in a hurry to leave so they could file their story.” She describes it as trying to grab something then getting out.

“That felt really bad to me,” she says. In one instance she remembers going to trenches in the middle of nowhere. Soldiers would be so happy to see visitors. They’d bring out tea, cook borscht, lay out everything they had, “trying to host us.” And then the security advisor would say, “Time to go. We leave now. And we’d just say goodbye and leave,” she adds.

With civilians, it was the same. “We’d arrive in these SUVs—Land Rovers, Canada Goose jackets, body armor, helmets—and sit there with grandmothers, kids running around,” then suddenly she recounts, someone would say, “We have to go. Shelling is coming. Good luck staying here.”

Today’s fast paced news cycle quickly moves past coverage of wars, leaving the long-term human impacts underexplored. “The war’s human side is deeply underrepresented,” Sopova underlines, stressing that the conflict’s effects on civilians are more than often overlooked in favor of rapid headlines.

While their work is political, Sopova and Taylor-Lind have intentionally kept the focus on the personal lives of those affected. “We wanted to minimize politics as a form of protest,” they explain, aiming to highlight that private human lives matter just as much as political narratives.

Living in the US today, Sopova is pursuing a PhD in anthropology at Princeton. She explains that it’s why she went into anthropology in the first place, to dig deeper into the issues encountered in 5k from the Frontline.

“My dissertation focuses on everyday life in Ukraine whilst in a state of war, examining how people connect to objects and material environments.” What does home mean? What does losing your home mean? How to recreate a sense of normalcy? Right now, “I’m fully immersed in writing it,” states Sopova. Her aim is to create a version that Ukrainians—especially those she’s writing about—can truly connect with. It should be ready in a few years.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-707273464d1ff31c2d79c472b81e1827.jpg)

-ef906d8c7daeee38b707ac8966246a92.jpg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)