- Category

- Culture

New York Artist Yelena Yemchuk Shows Her Native City Kyiv in an Artistic Homecoming

In an interview for UNITED24 Media, photographer Yelena Yemchuk reveals that she returned to Kyiv with no intention of taking pictures—but an organic encounter with memory, muse, and the momentum of women staying behind in wartime, gave rise to the project Mnemosyne. Her first exhibit in Ukraine, it is currently on display at The Naked Room gallery in Kyiv.

When Yelena Yemchuk came to Kyiv in August 2024—her first visit in four years—she had no intention of photographing. Only through dialogue with her gallerist, Maria Lanko, who co-runs The Naked Room based in Kyiv, did the project Mnemosyne emerge.

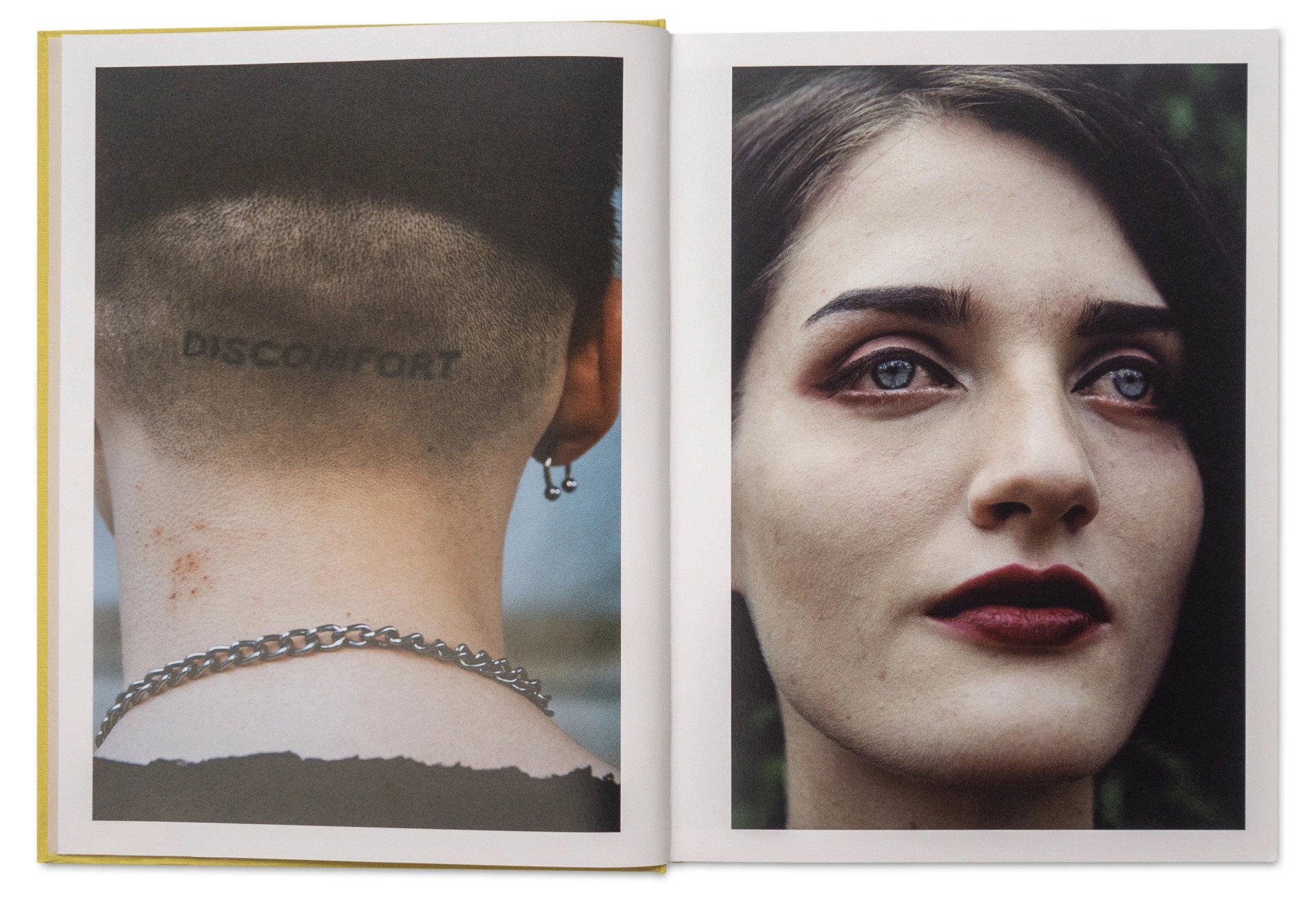

Yemchuk’s first exhibit in Ukraine, organized in conjunction with The Naked Room, Kolektiv Cité Radieuse, and the Institut Français in Ukraine, is named after the ancient Greek goddess of memory.

Extending back to 1991, a time when Yelena didn’t really take pictures yet, the exhibit transformed into a hybrid of collages and portraits.

The artist, who emigrated from Ukraine to the United States in 1981, stays deeply linked to her homeland. Her first photobook, Hydropark, was published in Spring 2010 and featured portraits of bathers enjoying the water, while simultaneously encasing the memory of a country in flux.

On equal footing to her stance as witness is Yemchuk’s unapologetic affinity for the concept of “muse.” Yemchuk mostly photographs people, which she sees as a collaborative act. This belief has permeated the majority of her work, which often circles around a central figure or figures.

In this interview, the photographer speaks of her love of accidents, her inspirations such as David Lynch and the city of Kyiv. The result is a down-to-earth conversation that firmly anchors Yemchuk among her Ukrainian counterparts, such as Boris Mikhailov, who noted in an interview with UNITED24 Media: “For me, the essence of photography is chance transformed into meaning.”

Intuition, feminine energy, and Ukraine

How did it feel being back in Ukraine after four years?

It’s like living a completely different life. You’re so present, so incredibly engaged. I can hang out with 25-year-olds and just learn. The conversations you’re having—they’re completely different from the ones you’d have in London or New York or wherever. It’s just a different world.

Oh, I fucking love it so much. I’ve always loved it. That’s why I keep coming back. So many of my immigrant friends who left when they were kids—most of them never went back. Not even once.

I guess I just keep coming back. I can’t stop. I couldn’t. It would feel horrible not to.

Do you see this intuitive approach as something maybe inherently feminine? I’ve heard you describe Ukraine as a woman before.

I don’t know. I always feel like women have more intuition than men. We all have it, but women are just more aware of it. Men are different—we’re all different. I feel like we experience the same emotions and feelings, but we don’t connect to them in the same way.

Intuition can feel like destiny. It’s connected to something ancient, almost spiritual. People associate it with being witchy or feminine. That’s how it’s framed.

I think of someone like David Lynch—he’s kind of my hero.

Yelena Yemchuk

I’ve said it in many interviews, but he’s the reason I became an artist. When you listen to him talk, it’s clear—he follows his intuition. You can have a plan, a clear path, everything set. But then something inside you says: “Look left.” And if you do, and if you’re open to it, something magical happens. That’s what I follow—my gut more than my mind. That’s a huge part of my work.

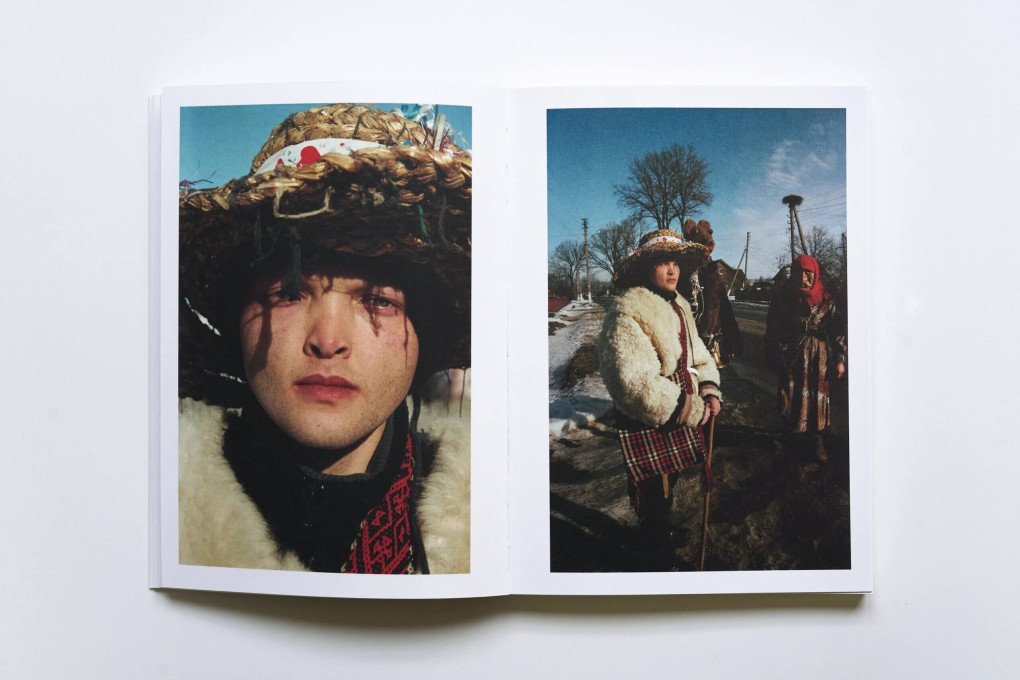

Like with Malanka [short film, 2023]—I had an idea, a basic script. A woman who’s an alien, a time traveler, arrives in this place. A man is looking for her. Why? I don’t know. But things start happening if you’re open. If you’re closed off, stuck in your head, trying to control everything—that need for perfection, for order—that’s such a masculine way of being. Women are just more open to accidents, to following the unknown.

That’s also why I say Ukraine is a woman. Some cities or countries feel masculine or feminine, and Ukraine just feels feminine to me. It’s instinctive. I could be wrong, but I feel it. I carry strong female energy, and I feel it reflected there. It’s interesting.

At the beginning, I just wanted to come home to Ukraine, see my aunt, do my stuff, hang out with my friends, be present. The fact that I started photographing was kind of weird to me, because I wasn’t planning it at all. But I guess it goes back to that female energy—I was just like, “What are these women doing here?” You know?

Women who could be living in Paris or London or wherever—they’re in their 20s or 30s, no husbands in the war, and they choose to stay. I don’t know… just talking to these woman made me want to take their picture. Because that’s part of history too. That’s important documentation—from a completely different perspective.

David Lynch and the creative process

What is your connection to David Lynch, and how have his ideas—like accidents and inspiration—influenced your work?

When magical things happen as I’m shooting—which they do all the fucking time—at this point in my life, you know, I’ve been doing this for 30 years now, you just smile. You know what I mean? I’m so aware of it when it’s coming. And then I’m in the right place, at the right time, doing the right thing.

It’s the best. We just finished part three of the short film trilogy that Malanka is part of. In the first short, we were shooting in Odesa. I had this vision—I wanted a fly to land on the actor’s face.

I asked my friend, who was the producer, “We need a fly.” We couldn’t find one.

In the last scene, the finale—she [the actress] is sitting. We’re zooming in—and the DP says, “Let’s do it again, it didn’t go right.” I say okay, and—I swear—a fly lands in the same place, on her cheek.

We’re all completely silent. And she’s so focused—this girl is amazing. She does this perfect little smile at the end. I’m like, are you fucking kidding me right now? When I send it to the sound guy, he goes, “What’s with the fly, Yelena? How did you—? I say, it was an accident. It just happened—it’s magic. I mean, there’s no other way to explain something like that. It’s the best.

With experience, you can now sense when you’re in the right place creatively—do you think that kind of awareness only comes with time?

When I think back to when I started shooting—really young—you constantly feel like you need to be in control. You feel like your vision comes from your control: you, controlling the situation, you, finding the thing. And it’s just not true.

First of all, photography is such a collaborative—and filmmaking, obviously—it’s such a collaboration between you and the subject. I mean, unless you’re shooting houses, or trees, or nature, whatever. But I mostly photograph people.

The magic really happens when that person is willing to share. That’s the best feeling—when you’re getting that emotion. To me, that’s the most powerful: being able to capture someone who’s not closed off.

That’s the gift. That’s my gift. My gift is not like, “Oh my god, I’ve got the best light set up—my lighting is insane,” you know? I just really think my ability is to connect with somebody—a stranger on the street, or whoever—and them feeling like they can open up to me.

Ethics and boundaries in photography

Have you ever had ethical doubts or conversations with yourself about photographing people?

My work is positive in a sense, but it’s not sugarcoated. I’m not trying to make something beautiful, per se. If I find it beautiful, I don’t give a fuck what anybody else thinks. It’s beautiful to me. Maybe that resonates with people who connect with what I’m doing.

But there are many times when I see something and think, “Oh my god, I want to take a picture of this person.” And it just doesn’t feel right. And I feel like that’s not okay. I know they’re not okay with it—so I just walk away. It’s really important to respect what’s happening. That kind of imagery isn’t respectful. There’s a line, you know? You have to feel that line instinctively.

You might want to take the picture—you think, “This is fucking crazy, this is insane”—but it’s not okay. It’s not okay because that person is vulnerable in a way where I’d feel like I’m taking advantage of them.

Even when I’m doing portraits, sometimes I can feel that they don’t want it. You can feel that. You need to be open, you need to respect boundaries. Because it’s very intimate. They’re sharing something with you. You’re taking something—but you’re also giving something.

And that’s the best exchange. For me, it’s more about the process. I don’t care as much about the outcome. I mean, I care—because I like looking at my books—but I don’t love showing so much. For me, it’s really about the actual experience.

There are definitely things that are not okay to photograph. I have a hard time. I could never be a war photographer, let’s say, just personally. I don’t think I could have my camera up if I saw someone being hurt. I’m just too sensitive. I would lose my shit.

But there are people who are amazing at disconnecting that part of themselves. They’re just like, “I need to document this. The world needs to see it.” I take my hat off to those photographers. Not to mention—they’re risking their lives.

How Mnemosyne began

What was the first image that made you realise you wanted to take pictures during the full-scale invasion?

We were just hanging out in Kyiv. My friend, who helps me produce stuff, was like, “Do you want to take some pictures?” I said, “No, I’m good. Let’s just hang out.”

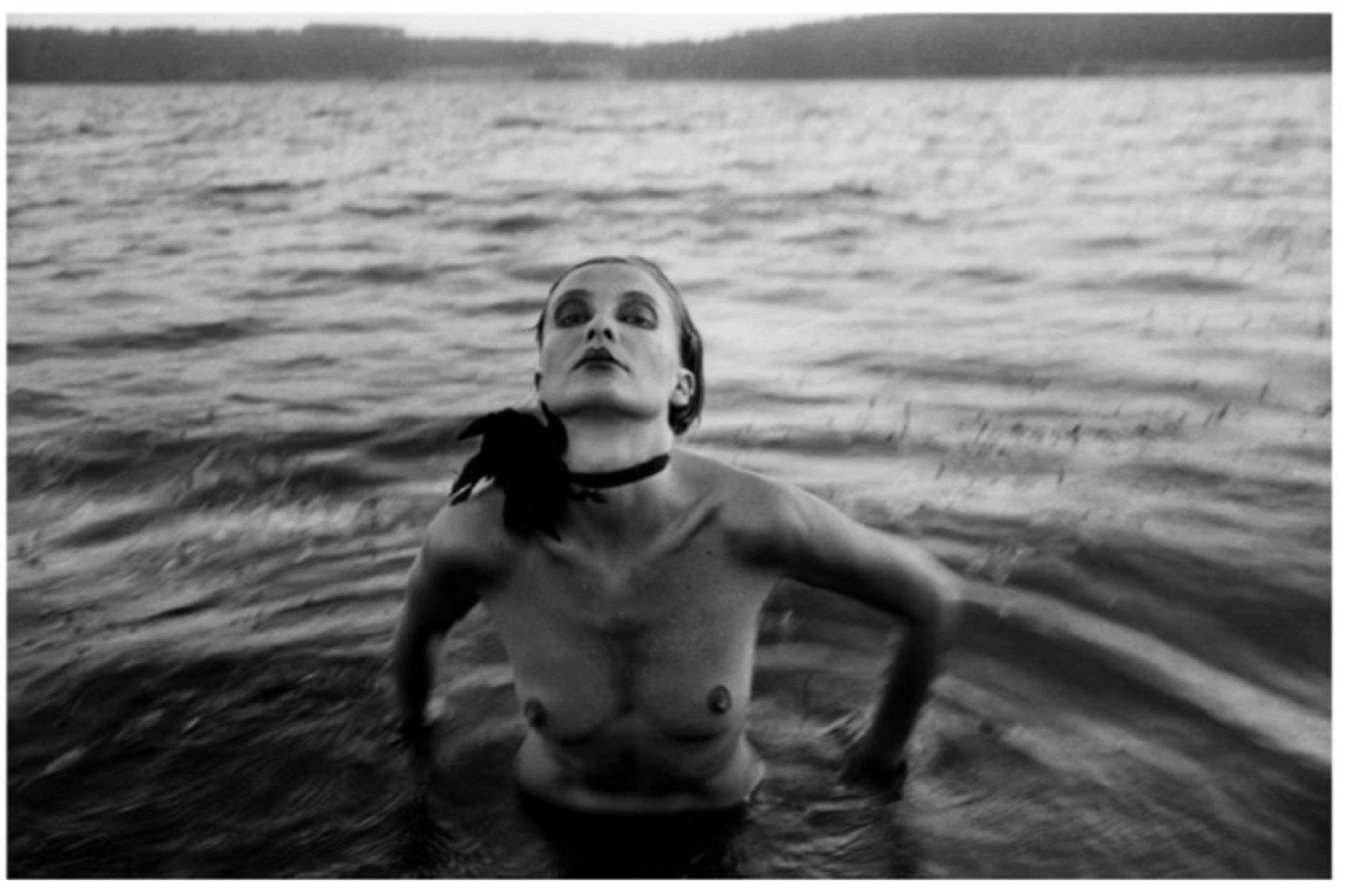

We were with some of our girlfriends, and it was beautiful. It was summer—August. It was hot. She said, “Should we go somewhere to swim?” Then I thought, why don’t we get a few women together? It’s beautiful, it’s nature—and I’ll just take some portraits. That’s how it began.

Did you get the film developed in Ukraine?

No, I usually bring it back with me.

You don’t immediately look at what you shot—is that a part of your process?

I usually shoot and then bring it back to New York with me. Last year, I was living in London, so I brought it back there and had it processed. I didn’t think much of it, really, just “Oh, these are nice pictures.”

The trip was more about moving my aunt—I moved her from Miami back to Ukraine. That was the main purpose. I spent a little time in the Lviv region and then about a week in Kyiv.

When I got back, I felt full. Something that had been missing was suddenly put back in. I figured I’d come back again in the spring or whenever.

Then Maria Lanko emailed me from The Naked Room. She heard I was in Kyiv and missed me at the gallery—I always go to the gallery. She told me she had been talking to people at the Kolektiv Cité Radieuse in Marseille and that they wanted to do a dual exhibition with me. That’s how the conversation began. They asked if I’d started a new project, and I said, “No, not really.” Then they said, “Well, maybe the show could be your documentation of bringing your aunt back. Did you take pictures?” I said,

“I always take pictures.”

Yelena Yemchuk

So we thought maybe it’s more like a diary. We kept talking, and something in me wanted to continue. I went back to Lviv in June and photographed a bunch of women. It felt organic.

In Lviv, when I was photographing—mostly girls I know or had photographed four years earlier—what they said made me feel like it was important. They said the experience made them feel really beautiful. It made them feel excited about being photographed. That, to me, gave me the strength—or the desire—to continue.

Your project is called Mnemosyne, and this exhibition is a three-part series—what does the title mean and how does this chapter fit into the larger body of work?

It’s the goddess of memory in Greek. When we started thinking about this exhibit, I was scanning a lot of old negatives.

When I came back from my first trips to Ukraine—the first time was in '91—I didn’t really take pictures back then. I was studying in art school, but I didn’t really know what I was doing yet. There are only a few photos from that time.

Then in 1997, I started going back to Ukraine after college, and those were the first images I made there—’97, ’98, ’99, 2000, 2001, 2002. Those trips shaped the early archive. Of course, I printed some of the work—this was still the darkroom days. I always knew there were good images there, but I hadn’t really gone back to look at the archive in a long time.

So I started digging through all my 90s and early 2000s negatives—I scanned the Ukraine images, and when I did, I realized: wow, there’s actually some really good stuff here. So part of the exhibit became about showing those early images—when I first started returning as an adult—and pairing them with the new work I’ve been doing. And because the archive is now old enough, I realized I could actually start collaging with it.

I’ve always worked with found imagery and made collages as part of multimedia projects. But now, I could do that with my own work. In the show, there are five collage pieces where the background is made from my 90s photos, and the girls I’ve been photographing for “Mystery of a Memory”—a project I started in 2019—are cut out and placed into those scenes. I dressed them to resemble the women from my childhood.

It was so fun—I love working like that. The title really ties it all together. These are memories from my childhood, memories of going back, and now, when I look at those 90s images, they’ve become historical. That’s so strange to think about. They’re capturing Kyiv—mostly Kyiv—and it doesn’t look like that anymore.

From process to memory

As your work has evolved, have you felt it shift from being personal to becoming more of a memory of a place—a record of a country’s destiny as much as your own?

I knew when I was shooting Hydropark—I mean, it was 2005 to 2008—I knew Kyiv was changing. I knew I was going back to a childhood place and trying to capture the last moments. I could feel it. You can sense things—intuition again—you can feel it. I sensed the urgency of doing that project then.

I felt the same urgency when I shot Odesa. I knew it was important because I was capturing something just before it changed. I didn’t know there was going to be a full-scale war—who could have known? But the urgency with which I shot Odesa felt very real to me. I needed to photograph the kids there, the feeling, the beauty of the city. Same with Hydropark—I thought, “This isn’t going to look like this forever.”

But when I was shooting in the ’90s, I had no idea. I was just a young photographer walking the streets. I had just started enjoying that. When I was in art school, I mostly did staged work—I didn’t think I’d enjoy documentary-style photography. It wasn’t like, “This is the kind of photographer I want to be.” It just came naturally. I was coming home, and I wanted to see what was going on outside. I wanted to capture it. That was it.

Showing that work now for the first time is really exciting.

What’s your relationship to archiving as a photographer—are you methodical, or more chaotic with your negatives and materials?

It’s the shit that wakes me up at four in the morning. You know what I mean? Drives me nuts. I shoot on film, so you always think, “After this, I’ll organize everything,” but it’s just a nightmare. It really is. I’ve started working with someone now, helping me sort it all—because now we’re dealing with negatives and scans. There are no contact sheets anymore, just endless scans.

I hate it. I can’t wait for it to be done.

Has your approach to archiving evolved as your work continues to gain a wider international presence?

No, I just want to be organized. The first thing that I actually put out in the world as a fine artist—whatever, fine art artist, photographer—was Hydropark. I knew I wanted my first book to be in Ukraine. That was important.

The first book I put out has to be from my country. At that point, nobody was even talking about Ukraine—

“Ukraine, what?”

Yelena Yemchuk

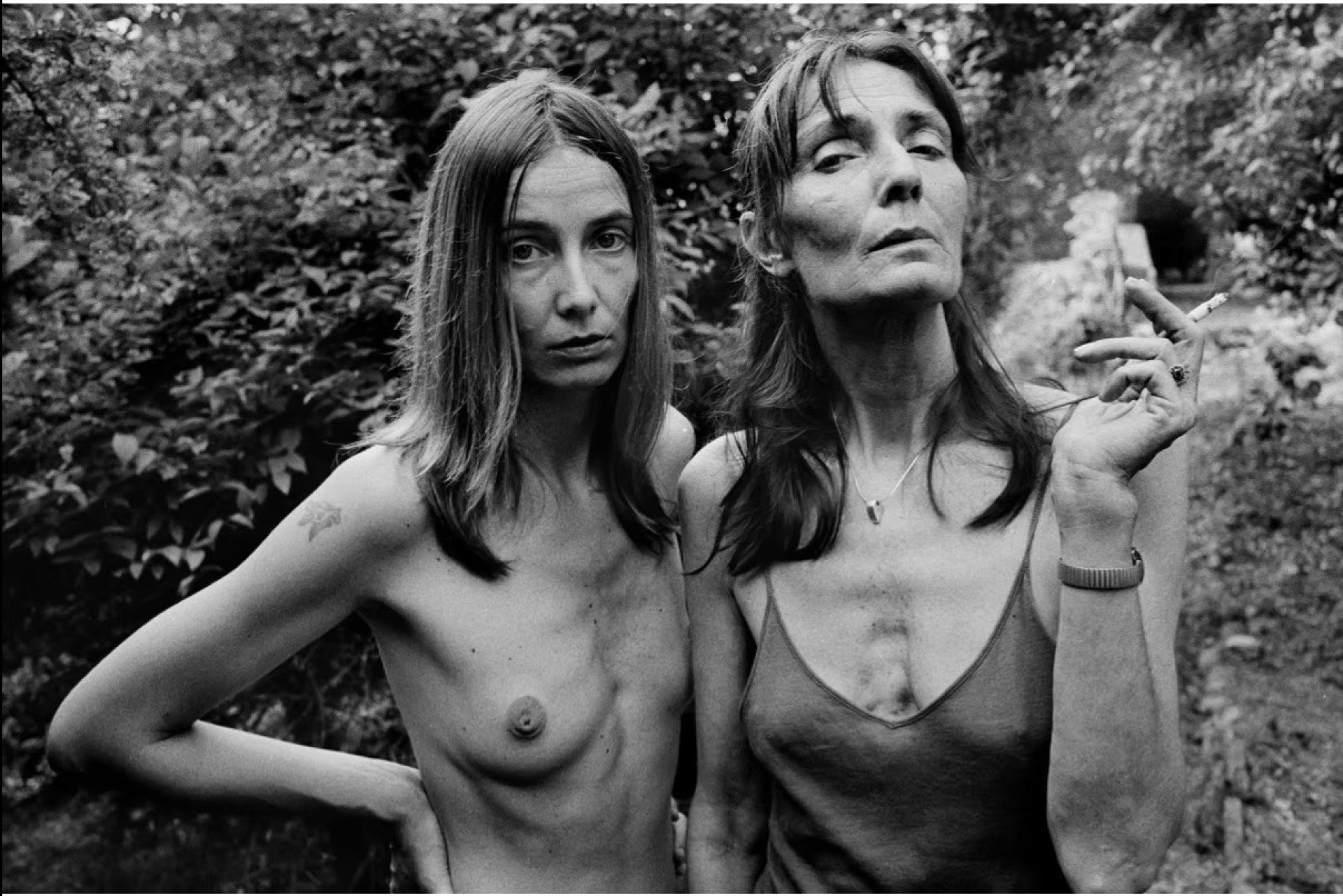

There was a project called Anna that I worked on in late 2017, and it began with me archiving. That’s a perfect archiving story. I had someone helping me scan; we had a really good scanner at this place. I was like, “You know what? Let’s scan all these Anna-Maria negatives.” She was a girl I met in New York; we worked at the same restaurant—an Italian girl. She moved back to Italy. When I ended up going backpacking through Europe with my boyfriend at the time, I landed in Italy for two months. I had just gotten out of school, and I started photographing her and her mom.

We continued for 20 years. I mean, I still shoot her. And I just thought, “Let’s organize Anna-Maria.” Then, somehow, this Japanese publisher reached out to me, saying he wanted to do a book. I sent him a few different projects I was working on, and he picked the one with Anna-Maria, and we ended up doing a book.

But if I didn’t have all those negatives scanned at the time, I wouldn’t have been able to say, “Here, here’s this work.” I wasn’t scanning them to do a book—I was just scanning to organize, and we did this really cool book about a friendship between two women. With her, I learned how to be a photographer, you know?

There are all these experimental black-and-white images—mostly black and white—of me at 23, 25, 27, 30, 40, and beyond, into our mid-40s. Me photographing this one girl.

That part of archiving is great. You just keep shooting—because you want to, or because you need to. Then, when you organize it, it might become something else. It might become a book. It might become a show. It might become nothing. But at least you have it organized.

The photographer and the muse

Do you think, in a way, you become a photographer through your relationship to the people you photograph?

In a certain sense, I was becoming a photographer because of the relationship I was creating with this other woman I was photographing. That made me a photographer.

Through the process of constantly experimenting with somebody, you start to grow. Because, you know, for me at that particular time, you need someone—like, you have your friends at school, and we learned from each other too. We would photograph each other, and through that constant experience of learning, you grow.

And with Anna in particular, every time I would see her—which would be once a year, or every two years—I came back to her with all the other things I was doing. I came back with different knowledge. So the next time we shot together, it was like: “Let’s try this,” or “Let’s try this camera.” You need that person.

I love a muse. I love photographing the same people. Even with Mabel, Betty & Bet, and Malanka, and Futura, which is the last—it’s all this one woman that I met in Odesa. She stars in all three films. I love that collaboration. That, to me, is heaven. To find someone who gets you, who wants to collaborate on such a personal level—I love it.

And my first muse was a boy. It wasn’t romantic; it was my boyfriend’s best friend. But he had the most amazing face. It started with a boy, just because I thought his face looked like something out of a silent film—I was super into silent movies. My second muse was Anna Maria. And that’s still going. Every time I see her, I still want to photograph her.

-8321e853b95979ae8ceee7f07e47d845.png)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)