- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Can Horses Really Heal War Trauma? The Bucha Stable Giving Ukraine’s Veterans New Strength

Horse therapy is emerging as a vital force in Ukraine’s struggle to heal from the brutal toll of war. For soldiers wounded physically and struggling with PTSD, these animals offer more than companionship, they provide a pathway to recovery that blends physical rehabilitation with deep psychological relief.

Bohdan and his wife built their stables from scratch on what was once an empty field outside of Bucha in January 2019. As the Russians moved into Kyiv and the towns and villages surrounding them in 2022, Bohdan and his wife watched the news helplessly, unable to visit the stables.

There were two lots of Russian forces that would occupy the stables. When the first batch arrived, they told the few workers left on site that they had ten minutes to leave, then they moved in. They would stay for less than 24 hours.

“They wrote on that activity log that they fed them [the horses] and gave them water,” Bohdan says. After that, Russian tanks came from Belarus. This second lot of Russian forces killed five of the 26 horses, letting loose seven others, and trashing the stables. When Bohdan and his wife returned, “Everything was broken, beaten, smashed,” says Bohdan.

“Russians came. Everything was stolen. Dead horses, dead dogs.”

Bohdan

Stable Owner

The photographs of the stables after the Russian retreat radiate an eerie energy, as the faces behind such violent desecration remain unknown. Yet, the proof of their passage is clearly tangible. Russian military rations lay empty in a dry field, a German shepherd which has been shot in the head is sprawled out with his mouth open, bloodied Russian uniforms lay amid mountains of trash in the stables kitchen, and dead horses are dotted around the exterior dressage arena, laying their heads turned up, stable blankets still on.

Bohdan is jovial, around 50, and an ex-biker, positive he speaks in short sentences, breathing heavily as he recalls the state of his stables. Just getting rid of the piles of ammunition shells, trash, and general destruction took four months to complete. Now, more than three years after Russia’s 2022 invasion, young girls in pristine equestrian riding gear share the dressage arena with veterans, some of them amputees, severely injured, or living with PTSD.

The science behind horse therapy

Twenty years ago, Bohdan met Tetyana Grubenyuk—now the head of NextStep—back when they were both part of a motorcycle gang. A medical rehabilitation center established in 2015, NextStep Ukraine, modeled after the US-based Next Step Fitness and run by the nonprofit Revived Soldiers Ukraine, addresses the shortage of state-funded psychological care and rehabilitation. Since 2014, the NGO has volunteered with veterans and in 2022 launched an Equine Therapy program inspired by Bohdan and the stables.

Therapeutic riding helps improve muscle tone, coordination, balance, and confidence in soldiers with traumatic combat-related injuries. Riders actively guide the horses under non-therapist instructors, enhancing sensory and motor skills. For those with amputations or spinal cord injuries, horses support the recovery of posture and physical control.

Riding horses can seem like a superficial activity in the face of a grave, life-changing injury, but Bohdan challenges this idea, recalling his first experience watching severely injured soldiers interact with his horses: “There was a clear difference between before and after. I saw their faces literally light up. The energy in the room changed.”

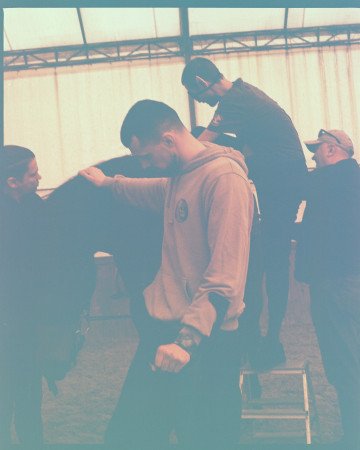

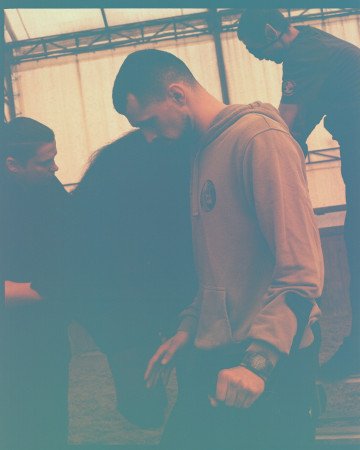

Grubenyuk firmly believes that someone’s physical level can exceed their pre-injured state. “In reality, sport is not only for the ‘able’ as is commonly thought,” she says as 30-year-old Vsevolod, a Ukrainian veteran, gets up on a towering brown horse named Playboy, lying his whole body along the horse and hugging him with his hand and legs. It’s his first time on the course.

“Emotional contagion,” better understood as the mirroring of human emotions by animals, is particularly strong in horses. Their behavior changes in response to the person’s emotional state. A horse has natural empathy and a non-judgmental presence, which helps people develop emotional regulation and build trust in their own abilities, states Dr Clare Thomas-Pino, senior lecturer in Human-Animal Interaction with Psychology at Hartpury University in Gloucestershire, England.

More importantly, bonding with horses triggers the release of oxytocin, a hormone associated with trust and positive social interactions. This chemical response occurs in both humans and horses during positive interactions.

Horses help patients take their first steps

When Vsevolod was in the Netherlands for rehabilitation, he recalled the staff’s approach as cautious and fearful. “I could see it, feel it,” he says. Back in Ukraine, Vsevolod spoke to a surgeon about his injured leg. He was told he needed to walk through the pain, “through the tears.”

The surgeon warned Vsevolod that his leg would “turn into jelly” if he didn’t walk. Vsevolod begged the doctor not to amputate it, and from then on, he stopped using a wheelchair. “I started walking on crutches, and about 3-4 weeks later, I was already walking around the house without them,” he says.

In the first half of 2023, some 15,000 amputations occurred, Ukraine’s Health Ministry reported. It was not specified how many of these were soldiers, but because of the scale and nature of the war, most are likely to be military personnel. In just six months, Ukraine saw more amputations than the UK had through out all of World War II, when 12,000 service members lost limbs.

Excited, Vsevolod is helped off the horse. “You reconnect with another creature, and it seems like trust in a living being is restored,” he says. “Now I understand why people spend so much time with them.”

In this instance, all the participants in the next phase of the rehabilitation program were men. Coming to terms with the vulnerability imposed by a life-changing injury may be the most difficult challenge of all, and many male soldiers refuse to open up, as reported by Ukrainian military psychologists.

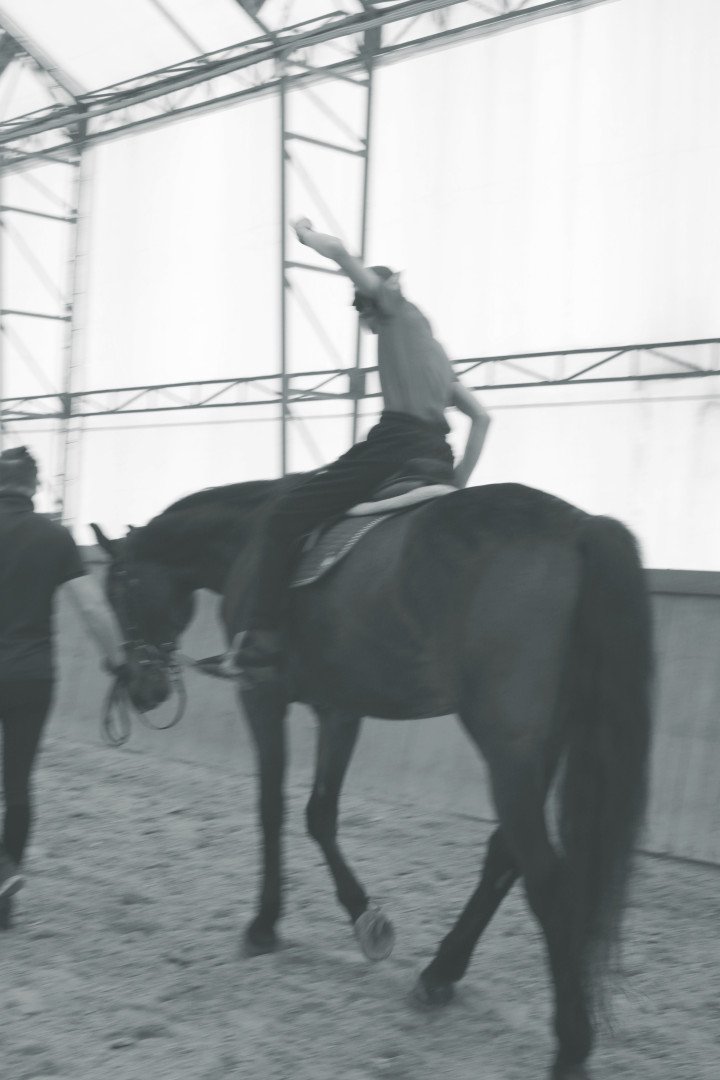

Another Ukrainian soldier, Rostyslav Prystupa, rides with confidence and ease, a slight smile on his face as the horse turns the corner of the dressage arena. Spirits are high, and Prystupa, with his high cheekbones and dark hair, could be mistaken for some kind of prince. Wounded in Mariupol, he lost the ability to walk following a spinal cord injury, “No one understood why I couldn’t walk,” he says.

Preskupa was captured in May 2022 while defending the Azovstal steel plant and remained in Russian captivity for about a month and a half. He required evacuation by helicopter, though he was never evacuated. In the end, Preskupa was exchanged and taken to a hospital in Zaporizhzhia, where he was informed that a fragment was lodged in his spinal cord and surgery was necessary.

After a long rehabilitation period, he joined Next Step in 2023. Initially, he mostly used a wheelchair and stayed in a professionally equipped house. Over time, he learned to use crutches and was able to walk between 50 and 150 meters with them.

Most people in the equine therapy program at Next Step remember the first time Preskupa stood up from his wheelchair. As of now, Preskupa has nearly fully regained movement, though he still walks with difficulty.

Riding since childhood, Preskupa recalls his first experience on horseback, herding cows: “I just got on and rode. I was comfortable, I felt like I was flying.” His ease with horses is on show at the stables, calling up to the horse as he makes jokes with Bogdan and the instructor. Afterwards, he describes the benefits as helping him feel emotions.

When nature feels like war, horses teach peace

For Yulia Komarova and Oleksandr Ihnatenko, “people who love horses always work with them,” they say. Oleksandr started off working as a veterinarian in the West of Ukraine.

“It was my dream,” he says about starting his horse farm, which consists of a herd of about 81 horses. Up in the Carpathian mountains, they adapted their civilian equestrian therapy program for soldiers, known as EquitoursUA (NGO Equine World).

Before the war, they operated a similar initiative known as “Equine Guests,” which catered primarily to civilians. “Initially, we thought: why can’t soldiers, who are also ordinary people, go to this course?" says Ihnatenko who is visibly passionate and invested, always thinking of future iterations of the program.

“For many soldiers, nature has become associated with threat,” he says. “Trees, fields—they’ve seen those explode or hide danger. Nature itself feels like an enemy.”

One veteran described stepping outside at night and spotting glowing dots on a cabin. His first instinct was to assume it was the reflection of a Russian thermal scope, only to discover it was an owl. That shift from perceiving a threat to experiencing nature simply is the kind of transformation that Komarova and Ihnatenko aim to create in soldiers.

For most of the program, participants remain on foot. They mount a horse twice throughout the course, and only briefly each time. As opposed to a trail ride through the mountains, in this instance, it is more about building a connection with nature and the horses. Often, it’s enough to simply feel the horse breathe.

This contact helps. They realize the horse feels them too, it reacts to their mood. It reflects their state of mind. Horses are incredibly sensitive. That feedback helps build trust and self-awareness.

Oleksandr Ihnatenko

Head of EquitoursUA (NGO Equine World)

Participants are usually placed bareback to enhance their awareness of the horse’s movement and presence. For those with amputations, the experience is less about traditional riding and more about fostering a sense of connection.

Ihnatenko observed that uneven terrain played a role in recovery; walking along mountain trails naturally stimulates physical activity, often without participants realizing it. The varied landscape encourages movement, even in the presence of pain or physical limitations.

“They see how the herd functions, how it protects itself, how it maintains hierarchy,” he says. “This is a real herd: stallions, mares, foals. If someone acts wrong, the horses respond because they live in a natural social structure. It teaches people a lot, just by watching. As Hippocrates said, ‘The doctor treats, but nature heals.’ That’s our foundation.”

Ironically, Ihnatenko says the program, originally designed to help veterans reintegrate into civilian life, has, over time, led him to learn from the veterans instead, adapting to their way of seeing the world. “It’s humbling,” he says. “And it’s powerful.”

PTSD meets peer trust—and a climbing wall

In Kyiv, a group of severely injured veterans meet at their local climbing wall, preparing with resistance bands, and doing push ups on the soft colorful floor. All are undergoing or have undergone rehabilitation with Next Step Ukraine and started climbing thanks to the Ukrainian mountaineer Alevtyna Kovalchuk who initiated climbing sessions with veterans through Climb to Life UA.

Ukrainian soldier Roman has kind eyes and is shy, talking with a lot of enthusiasm. Wounded in 2022, his recovery took about a year and a half. He underwent multiple surgeries and rehabilitation phases, spending roughly a year bedridden before beginning to use a wheelchair.

The notion “peer trust” is a psychological concept referring to the trust and rapport developed between individuals who share similar experiences. In the rehabilitation of soldiers, peer trust plays a crucial role in the healing process, particularly for soldiers coping with PTSD.

“After combat and injury, something changes in you,” says Romil, as other veterans scale up and down the climbing wall behind him. “You trust someone who’s been through what you’ve been through, even if you just met them today. There’s an immediate connection.”

Each time he climbs up the colourful wall jutted with an array of holds, it is an improvement on the next and faster. On the subject of NextStep, he says, “Programs like this, and interaction with civilians, help you re-enter civilian life. You’re forced to engage, to trust.”

Hanging high up off the wall, suspended by the climbing rope, the success of the activity becomes apparent. Trust is the first step to reentering civilian life, and is gained in incremental steps, through connection to people, horses, or climbing walls.

As trust builds, the physical condition improves. Roman remembers seeing it himself.

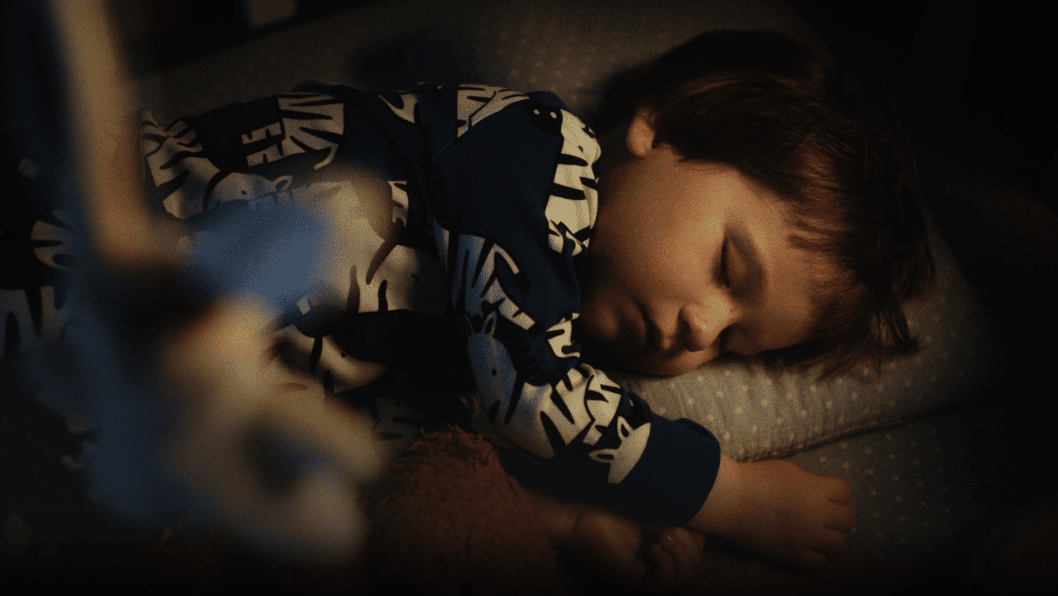

“It’s hard to explain—it’s like some invisible changes happen,” he says. “A child who usually needs side support in a wheelchair suddenly starts holding their back straight. They calm down, and the tremors go away.”

The same goes for Prystupa, a close friend of Roman’s: “Doctors said he’d need a wheelchair for life, but he stood up and said, ‘Forget that, I’m going to walk.’ And now he walks.”

Roman remembers seeing Prystupa riding the horses at the stable, seeing his shaking stop. “Almost like an old magic trick,” says Roman. The emotional transformation, he says, is striking.

Yan, who is at the climbing center with Roman, is 21 years old and scales up the climbing wall, pushing himself, seemingly mapping out his ascent as he grasps the holds, right until his head touches the ceiling. He was injured in 2024, during an assault on a Russian position, when a bullet tore through his palm and got lodged in his shoulder.

Abseiling down, the climbing rope whirring, he says, “I came in feeling okay, maybe a little tired because I didn’t sleep well. But after the climbing session, I feel amazing—full of energy.” Showing a picture on his phone, taken before his injury, Yan stands in a snow-covered field, a line of white capped trees behind him, his youth apparent under his helmet and full tactical gear.

Yan’s attitude to his injury adapted quickly: “At first, I used to hide my arm. But over time, I thought, ‘Why should I? ’Eventually, I just stopped caring.”

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-7f50738271c122a9b5e663cb80703dd6.jpg)