- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Ukraine’s War Veterans Trade Rifles for Paddles in Kyiv’s First Ever Dragon Boat Race

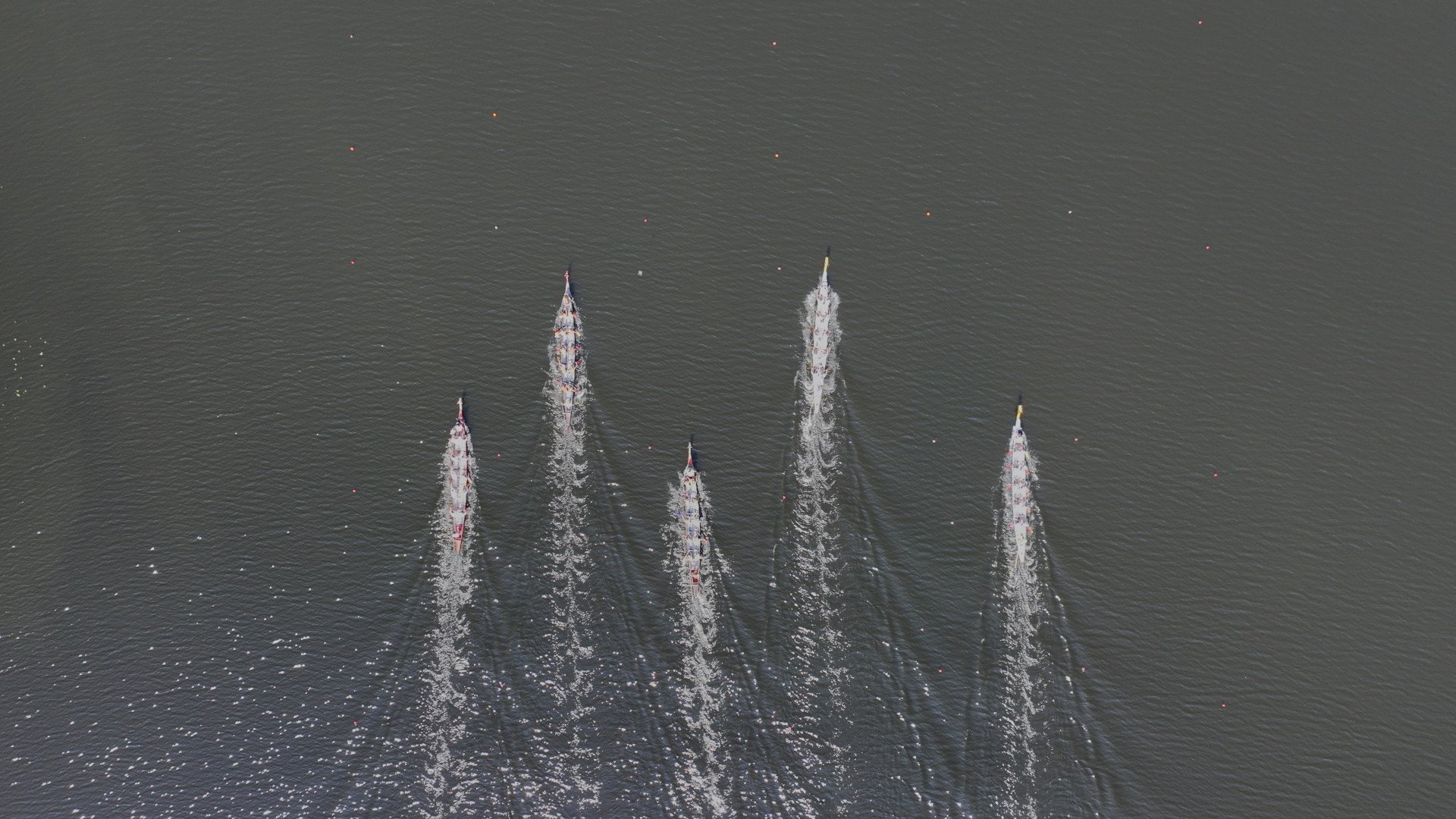

“1,2,3,4!” The commands echo across the river as blades slam in unison. On Kyiv’s Trukhaniv Island, soldiers and veterans swapped rifles for paddles, driving long dragon-headed boats down the Dnipro to the beat of a drum in Ukraine’s first-ever dragon boat race.

Dragon boat racing relies on rhythm and teamwork. About 12 people sit opposite each other in two lines, pulling their oars through the water in time to a drumbeat. The drummer sits at the bow, shouting the cadence that binds the crew together. On Saturday, September 6, roughly 20 teams competed on the Dnipro River in boats built for 10 and 20 rowers. Each team raced three 200-meter heats: a preliminary, a semifinal, and a final.

From frontline to finish line

This was the first competition of its kind in Ukraine for active service members, veterans, and disabled veterans. The festival took place on Trukhaniv Island, the green river island across from Kyiv’s Podil district, reachable by a short walk over the Parkovy Pedestrian Bridge. For decades, the island has been a space for running, cycling, and weekend picnics. On this day, it became something different: a meeting ground for those who once fought together in war, now sitting side by side in long red and blue boats with dragon heads fixed to their bows.

“Currently, the team of the NGO ‘Veterans of the 128th Territorial Defense Battalion of the Dnipro District of Kyiv’ under the coaching of Artem Skrypnyk is undergoing training to participate in the competitions,” the Dnipro Regional State Administration reported ahead of the race.

Healing through teamwork

The symbolism was unavoidable. The counts of one, two, three, four, called out with each beat of the drum, echoed the cadences shouted on training grounds and battlefields. The same instinct of collective rhythm—of falling into step with those beside you—moved from combat drills into the waters of the Dnipro.

“Dragon boat racing is an international sport that embodies the spirit of unity,” states Anatolii Yehorov, a veteran who fought against the Russian full-scale invasion in Mariupol, and the director of Military Sport . The festival is meant to support wounded veterans as well as active service members. “It gives Kyiv residents, who we warmly invite, the chance to cheer for our heroes,” says Yehorov.

The festival itself was like a large community picnic. Families gathered in the shade of trees, and the lapping of the river carried over the shouts of encouragement from the banks.

Danylo, a soldier of the 5th Separate Mechanized Brigade, carried the memory of his injuries as clearly as the battles he fought. Near Bakhmut in 2022, a Russian anti-tank missile tore into his chest, breaking ribs and collapsing his lung. “I almost died,” he says, describing the open pneumothorax that left him gasping for breath until comrades pulled him out. The wound was his second—the first had come years earlier, before stints in Afghanistan, Somalia, and Libya. “That training saved my life,” he says.

Just by him, soldiers in matching brigade T-shirts joked and leaned back on the grass. Maksym, of the 210th Assault Regiment, sat by the water as his colleagues teased one another. He was calm, smiling, and reflective.

“I myself joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine, taking up arms almost from the first days,” he said. “At first, I served in a volunteer unit, and later I moved to a specialized infantry unit.”

Since 2025, he’s been stationed in Kyiv, focused mainly on logistics while remaining with an assault regiment. His unit operated in the Kursk region and Sumy region, now they are located in the Zaporizhzhia and Pokrovsk regions.

“In other words, we are active in many places,” Maksym says. “For us, taking part in these competitions is first and foremost about strengthening our team spirit. It is about showing everyone that we don’t give up, that we can work together and achieve success.”

Maksym says now it all feels natural, “Whether you are in uniform or back in civilian life, this has become part of who you are.”

Wanting to recover is already a win

The connection between rehabilitation and competition was visible. Polina Nepomichna, who works in a psychiatric hospital unit for soldiers and is a board member of the Rehabilitation Forces of Ukraine, spoke of the inner drive required for recovery.

“Together with other soldiers taking part, this event brings everything together—it really touches on all aspects of recovery and improvement,” Polina says.

Having witnessed many recoveries, she remains steadfast to one point: It comes down to taking action and having the will to get better. “First of all, you always have to think about yourself,” she says, “The will to recover already gives you a measure of success from the start.”

Polina explains it this way: if someone wants to join a competition, they might not make the team this time, but simply having that drive already says a lot. She says recovery is no different.

She knows how hard it is to summon such determination as the soldiers face heightened PTSD: technological advances are making the war more deadly for soldiers, with 60 to 70% of all battlefield casualties now caused by drones.

The same goes for civilians, Polina explains the PTSD is shaped by what happens in everyday life and Ukrainians' everyday life is Russian drone and missile attacks—nonstop.

People, she says, live with PTSD every single day because even when they think today should be quiet, there is still always a chance that something will happen again, that another Russian strike might come out of nowhere.

“You are in this constant state of anticipation, unable to fully relax,” she says, moving her hands emphatically. With PTSD outside of war, the trauma usually feels fixed in the past, with some assurance that it will not happen again. In wartime, there is no such certainty for soldiers as for civilians: what happened yesterday, with all its horrors, can happen again. That absence of safety makes the experience profoundly different—and far more difficult.

Sport in a wartime city

Even in the light atmosphere of the race, looking out onto the water covered with white water lilies, listed in the Red Book of Ukraine, the official national list of rare and endangered plants, the threat of attack looms large.

As the day stretched on, Kyiv’s mayor, Vitali Klitschko, a former heavyweight boxing champion known as “Dr. Ironfist,” took the stage to hand out the trophies. His words carried echoes of the battlefield as much as of sport.

“We, Ukrainians, have already amazed the world with our spirit—the spirit of our people, our soldiers, our resilience,” he says. “Some once gave us only a few days, maybe a few weeks. And yet, for more than three years now, I can say proudly, we have been successfully defending our state.”

“I often feel not like a mayor, but like a defense minister,” he said on the sidelines. For him, the race was different, separate from the state of war he had come to exist in. Quoting Nelson Mandela while the crowd around him lined up for selfies, he added, “Sport has the power to change the world.”

In the end, it seemed pointless to talk of winners and losses, of competition, the point of the event so obviously otherwise.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)