- Category

- Opinion

What Russia is Doing to Crimea’s Indigenous People Echoes Soviet Repression From 81 Years Ago

Can a nation heal if its wounds keep reopening? On May 18, Ukraine marks 81 years since the Soviet deportation of Crimean Tatars. Russia’s repression continues, but so does Crimea’s resistance.

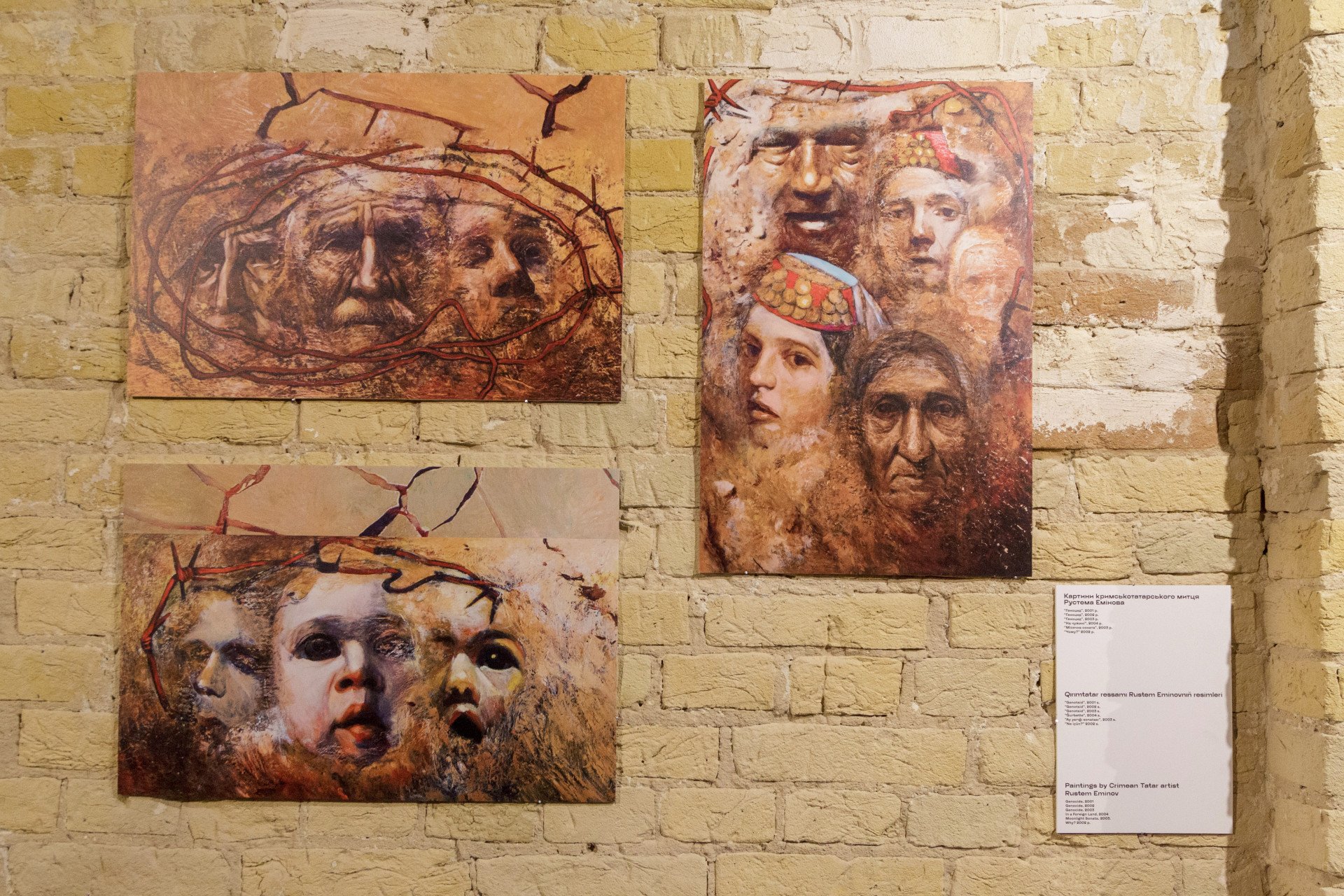

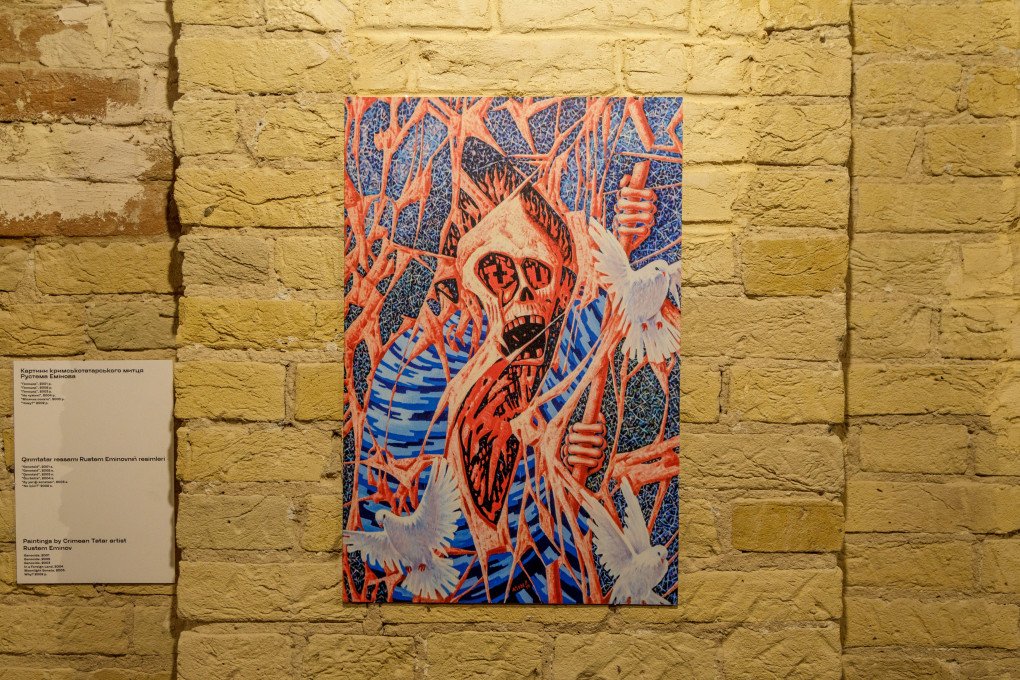

Last year, our office at the Crimea Platform opened an incredibly moving exhibition titled QIRIM İÇÜN / FOR THE SAKE OF CRIMEA. It commemorated the 80th anniversary of the Crimean Tatar people's deportation by the Soviet Regime. This exhibition, made possible through the tireless efforts of a large team, covered historical aspects, current events, cultural dimensions, and much more.

Yet, in my view, the most striking element of the exhibition was the deportation diary Butterflies of Paradise, authored by Mavile Khalil. At its core lies the true story of a Crimean Tatar girl, Khatidzhe Kurtasanova. She was only 12 years old on the day of the deportation—May 18, 1944. The diary also includes memories passed down by elderly people who lived through the deportation. Essentially, it became a collective image of thousands of stories about this crime of the Soviet totalitarian regime in 1944.

Just imagine: young Khatidzhe describes in her diary the entire harrowing process of deportation—the forced eviction from her home, the long journey from her native Crimean peninsula to far-off foreign lands, hunger, the loss of loved ones due to horrific conditions during the journey, the pain and confusion about what was happening, where their family was being taken, and why everyone was crying. Khatidzhe also speaks of the deaths of her little brothers and sisters before her very eyes, victims of hunger and the grueling journey in freight cars from Crimea.

Can we draw parallels between Khatidzhe’s story and our present-day reality? Sadly, yes. We have all seen how the silence surrounding past crimes has led to their repetition. That’s why Ukraine emphasizes that today, the Russian Federation—heir to both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union—is once again employing the old-new tactic of destroying Ukraine’s Indigenous people—those who historically formed on the Crimean Peninsula. The name for this imperial “know-how” is quiet deportation.

Russia’s 2014 attempted annexation of Crimea was a painful echo of 1944, reigniting trauma, reopening unhealed wounds, and instilling a very real fear of renewed deportation. House raids, repression, persecution—these are the new trials facing Crimea’s Indigenous people under Russian occupation.

“If you have a Russian friend, keep your axe close,” warns a Crimean Tatar proverb

The Russian attempted annexation of Crimea has revived a well-known Crimean Tatar proverb: “If you have a Russian friend, keep your axe close.” This was a topic we explored in the art project QIRIM İÇÜN / FOR THE SAKE OF CRIMEA. Russians have a deep-rooted drive to destroy identities different from their own. This impulse is an inherited trait from the Russian Empire, which sought to impose its imperial mark on the history of Crimea and its peoples.

For centuries, Crimea was a crossroads of tribes, peoples, cultures, and civilizations. The Crimean Tatar nation formed over hundreds of years, supported by the creation of the Crimean Khanate in the late 15th century, which spanned Crimea and the surrounding northern Black Sea steppes.

But in 1783, the Russian Empire seized the peninsula through deceit and war. The Crimean Khanate ceased to exist. Russia began transforming Crimea into a colony and a naval stronghold, destroying not only Tatar institutions but also their traditional way of life, customs, and culture. For the Crimean Tatars, 1783 marked a catastrophe, the tragic loss of statehood and the start of their displacement. Thus began Crimea’s “Black Century”—a time of decline, displacement, and repression for the Indigenous peoples under the Russian Empire.

The Crimean Tatars faced subjugation, land confiscation, and resettlement to less fertile and more arid lands within the peninsula. Many emigrated from their homeland. Historical records show that, over more than a century, three major waves of emigration occurred due to forced military service, pressure, and landlessness. By the end of the 19th century, Crimean Tatars had become a minority in Crimea.

In the 21st century, history repeats itself. Following Russia’s 2014 invasion, Crimean Tatars again became targets of repression. Take Reşat Amet—the first civilian victim of the Russian occupation. In March 2014, he staged a lone peaceful protest in central Simferopol. Days later, his tortured body was found. He had been brutally beaten, his eyes gouged out, his mouth taped shut. His murder was a savage warning to anyone daring to oppose the occupation or speak the truth.

Russian propaganda claimed Crimea accepted the invasion “peacefully” and without resistance. In reality, those who resisted were silenced permanently. Amet became the first victim in this renewed phase of Russian terror.

How Crimea resists now

Russia’s full-scale invasion became a test of endurance for all Ukrainians, especially those who had already endured occupation since 2014. Crimean Tatars are no exception—Russia launched a new wave of repressions against them. Forced conscription drove many men and their families to flee the peninsula. On social media, comparisons were even made between the events of 2022 and the 19th century, when Crimean Tatars were forced to leave due to conscription into the Russian Imperial army.

After over 11 years of Russian rule, the Crimean Peninsula has been turned into a military base and, essentially, a prison for its residents. Since 2014, human rights have been systematically violated. Independent media do not exist. Religious freedoms are suppressed.

The repression escalated after the 2022 invasion. Today, Russia illegally holds 223 Crimean political prisoners, 133 of them Crimean Tatars. The actual number is likely much higher, as many cases are partially or entirely concealed due to Russia’s control over information.

Those with views that support Ukraine to any extent face illegal searches, arrests, and torture. After the full-scale invasion, Russia has actively applied its so-called law against “discrediting the Russian army” to Ukrainian citizens in Crimea. The goal is clear: to silence everyone who resists the occupation, who posts on social media in support of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, or who openly condemns the Russian military. To date, around 1,350 such cases have been recorded. One documented case involved a woman fined because her 10-year-old daughter posted a video in support of Ukraine.

The number of such cases in Crimea has been steadily increasing over the years, while within Russia, this number is declining. This shows one thing: Crimea is resisting and will never become a legitimate part of Russia.

Cultural erasure as part of the Russian occupation

Alongside human rights violations, the Russians are systematically erasing Crimean identity and culture. The Russian Empire and later the Soviet Union tried to destroy Crimea’s authentic heritage by demolishing mosques, caravanserais, and Khanate-era landmarks, renaming places, and disfiguring the peninsula’s architecture.

Today, Russian officials build lavish palaces along Crimea’s southern coast to serve as new “symbols” of the region, continuing the legacy of cultural theft. Since 2014, Russia’s occupying administration has looted museum collections, conducted illegal archaeological digs, and plundered private and academic libraries and archives. They even destroy such iconic Crimean Tatar landmarks like the Khan’s Palace in Bakhchysarai. The site of Kalga-Saray in Simferopol was handed over to private developers to avoid cultural heritage recognition.

Construction of the Tavrida Highway unearthed numerous historical artifacts, the fate of which remains unknown. Crimea’s cultural heritage is also suffering under militarization, including at the Or-Qapı fortress, which is now entangled in military fortifications.

Another blow is the illegal excavation at Chersonesus Taurica , a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since 2014, artifacts have been unlawfully removed and transported to Russia.

Restoring justice and telling the truth are critically important for the world. So what can each of us do to help?

Permanent Representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea

Despite politically motivated persecution and the constant threat to their lives, Ukrainian citizens in Crimea—including Crimean Tatars—remain unwavering in their position: Crimea is Ukraine. Supporting those living under occupation, and doing everything possible for those illegally imprisoned by the Russians, is our collective duty. Each of us, wherever we are, can contribute to that effort.

To that end, the Mission of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (Mission), together with human rights organizations, launched the Letters to Free Crimea initiative, allowing anyone to write letters of support to political prisoners. These letters send a vital message: you are not forgotten, and we are fighting for your freedom.

In 2021, Ukraine’s Foreign Affairs Ministry launched a mentorship program for political prisoners, including citizen journalists. The ministry, together with the Mission and human rights defenders, is now working to expand the program to further spotlight the stories of those unjustly imprisoned.

Also notable is the Global Coalition for Ukrainian Studies under the patronage of First Lady Olena Zelenska. This initiative unites the Ukrainian Institute, the Presidential Foundation for Education, Science, and Sports, the Mission, the Crimea Platform, the Education and Science Ministry, and the Foreign Affairs Ministry. Its aim: to consolidate and expand Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar studies globally.

The European Court of Human Rights’ June 2024 ruling in Ukraine v. Russia (regarding Crimea) was especially significant, holding Russia accountable for systematic human rights violations in Crimea. The UN General Assembly and the European Parliament have repeatedly reported on these abuses. In May 2025, the European Parliament adopted a resolution demanding the return of Ukrainian children forcibly transferred and deported by Russia.

Equally important was the establishment of a Special Tribunal on the crime of aggression against Ukraine. It marks a major step toward justice, recognizing Russia’s war as an international crime that must be prosecuted.

Justice—especially historical justice—is essential. On May 18, Ukraine commemorates the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide. On this day in 1944, the Soviet regime began the mass deportation of Crimean Tatars from their homeland. This crime meets the international definition of genocide. Today’s Russian occupation echoes that repressive policy.

Ukraine, along with Canada, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Estonia, and Czechia, has recognized the deportation as genocide. We thank these partner states and urge other parliaments to do the same.

Ukraine’s Parliament adopted an appeal to foreign governments, international organizations, and parliamentary assemblies on May 14 to honor the victims of the Crimean Tatar genocide and unite efforts to end ongoing human rights violations in occupied Crimea. The appeal reaffirms Ukraine’s commitment to international law and UN human rights instruments, and highlights domestic legislation recognizing Crimean Tatars as an Indigenous people and acknowledging the 1944 deportation as genocide.

The US State Department’s 2018 Crimea Declaration is also referenced. It reaffirms the US non-recognition of Russia’s claims over Crimea and affirms a long-term policy of rejecting annexation.

The appeal was developed by the Mission’s team and submitted by the Ukrainian MP Tamila Tasheva.

The fight for Crimea continues

In 2024, to mark the 80th anniversary of the Crimean Tatar deportation, a Memorial to the Victims of the Crimean Tatar Genocide was unveiled in Kyiv at the initiative of President Zelenskyy. The site previously held a monument to Soviet security officers, glorifying a regime responsible for genocide. Its removal and replacement with a memorial to the victims represents a symbolic act of historical justice.

The fight for Crimea continues. Many Indigenous Crimean Tatars—soldiers and veterans—are now on the front lines, defending Ukraine’s sovereignty. Nearly every Crimean Tatar soldier fighting today descends from families deported in 1944.

Tragically, the Russians have once again denied the descendants of those targeted for destruction 81 years ago the chance to live in their ancestral homeland. But today, Crimean Tatar servicemembers, alongside Ukrainians and members of other Indigenous peoples, are resisting the occupiers and fighting for a free, strong Ukrainian state.

We must remember this. We must study history, learn to analyze, and—most importantly—draw conclusions so that the crimes of the past are never repeated.

-050b2b5554ed561c87f909a001f905b9.png)

-fb8f992b9d61f4272ace69523053416c.png)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)

-da3d9b88efb4b978fa15568884ef067f.jpg)

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-f3bede69822b36ac993a6cd5b65014f9.png)