- Category

- Opinion

“Are They Real?!” – How the Ukrainian Delegation Presented Fragments of Russian Weapons with Western Components in The Hague

A sanctions-focused conference recently concluded in the Netherlands, marking the first large-scale event dedicated exclusively to sanctions policy since the full-scale invasion. Participants—including government officials, experts, and representatives of major businesses—deliberated on how to enforce and strengthen sanctions and why Russia continues to evade these restrictions.

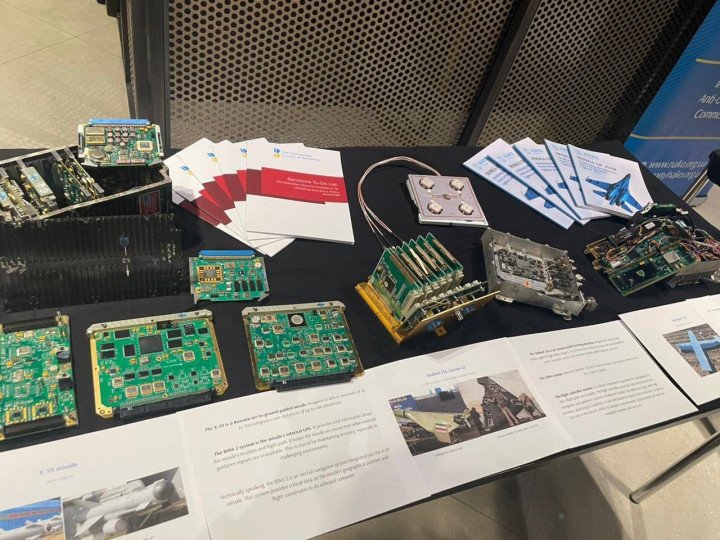

The Independent Anti-Corruption Commission provided visual proof of these evasions. As the only NGO invited to the event, and with the support of Ukrainian expert institutions, the Office of the President, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Ukraine’s Embassy in the Netherlands, we brought 14 compelling exhibits to The Hague. These fragments, retrieved from Russian missiles and Shahed drones that attacked Ukrainian cities, painted a vivid picture. Among the display were circuit boards from Kh-101 and Kh-59 missiles, UAVs (Forpost-R, Lancet), and an optical-electronic targeting system from a Kh-101 missile. We also showcased a gyroscope from the Tornado-S multiple-launch rocket system and other components.

All these systems contained microelectronics of Western origin, proving that Russia continues to acquire them despite EU and US sanctions. Crucially, these are not old stockpiles but often new components produced as recently as 2023 or even 2024. These Western parts, primarily microchips and circuit boards, serve as the “eyes” and “brains” of these weapons.

One striking example is a part of the navigation module of a Shahed drone, which includes four small antennas manufactured by Taoglas in Ireland. These antennas are resistant to electronic warfare (EW) measures. Initially, such modules had four antennas, but after Ukraine began jamming these signals, Russia upgraded the modules to include eight antennas.

This is critical because even these small antennas cause immense damage.

Drones have already destroyed dozens of buildings and taken many lives. For instance, Shahed drones alone have launched 15,366 attacks across Ukraine since February 2022. From January 1 to January 18, 2025, 1,431 Shahed drones have already been launched. Disabling these antennas could either halt these attacks entirely or at least make it significantly harder for Russia to procure the components.

In addition to Irish products, we found numerous American components, which form the majority of the Western parts. Microelectronics from the Netherlands, Switzerland, Germany, France, and other countries were also identified in Russian weapons.

For European attendees, it was essential to see these real weapons from battlefields—sites of war crimes against Ukrainian civilians, destroyed homes, and lost lives. One of the most common questions from visitors to the exhibit was: “Are these real?” They were surprised that such items could be brought to the Netherlands.

It was particularly interesting to observe the reactions of microelectronics manufacturers whose products were found in Russian weapons. We showed them their markings, the blast traces—concrete evidence that their technologies had been used in war. Manufacturers carefully examined and photographed the items.

The exhibition also caught the attention of Dutch Foreign Minister Kaspar Veldkamp, who attended with Finnish Foreign Minister Elina Valtonen and Latvian Foreign Minister Baiba Braže.

On the second day of the conference, we held a workshop for over 150 representatives from international companies in The Hague, including microchip manufacturers. The goal was to help them better identify the end users of their products and prevent Russia from accessing foreign components and technologies.

For example, Russian weapons often feature microprocessors from the Dutch company NXP Semiconductors, as well as products from LiteOn, Nexperia, and Philips. Dutch electronics were also found in the Msta-S self-propelled howitzer, the Iranian Mohajer-6 UAV, Russian fighter jets, and even the North Korean KN-23/24 missile.

Blocking all supply routes for these components is an incredibly complex task. Russia no longer obtains these items directly but uses intermediaries in third countries, such as China. However, with sufficient willpower from manufacturers and partner governments, it is possible.

What stood out most to me at this conference was the growing system of professional people, institutions, and departments within ministries of foreign affairs, finance, and trade. There is a clear understanding of the necessity and effectiveness of sanctions policy.

For these professionals, seeing that, even in the third year of the full-scale invasion, technologies are still reaching Russia underscored that their work is not mere bureaucracy—it is a matter of life and death for Ukrainians.

For the EU and the US, this also represents a real threat from the totalitarian alliance of the “Axis of Evil”—Russia, Iran, and North Korea.

-7e242083f5785997129e0d20886add10.jpg)

-cc5860059e044295cd5738becdb4e387.png)

-e27d4d52004c96227e0695fe084d81c6.jpg)