- Category

- War in Ukraine

The Men Learning to Live Again in a Land of Hidden Explosives

In Ukraine, where war has planted invisible killers beneath the soil, one wrong step can change a life forever. But what happens after the explosion? This is the story of Dmytro Huzhva and Dmytro Slepkan, whose lives were torn open by landmines, and how they found ways to live.

Dmytro Huzhva and his wife had just bought some food and were walking home through their neighborhood in Chuhuiv, a small city in Ukraine’s northeast. It was March 14, 2022—still the raw beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Then the sky split open.

A sudden barrage from a rocket salvo tore through the quiet street. One cluster munition landed right under Dmytro’s feet. The blast mangled his legs and sent metal shards flying through both sides of his wife’s hip.

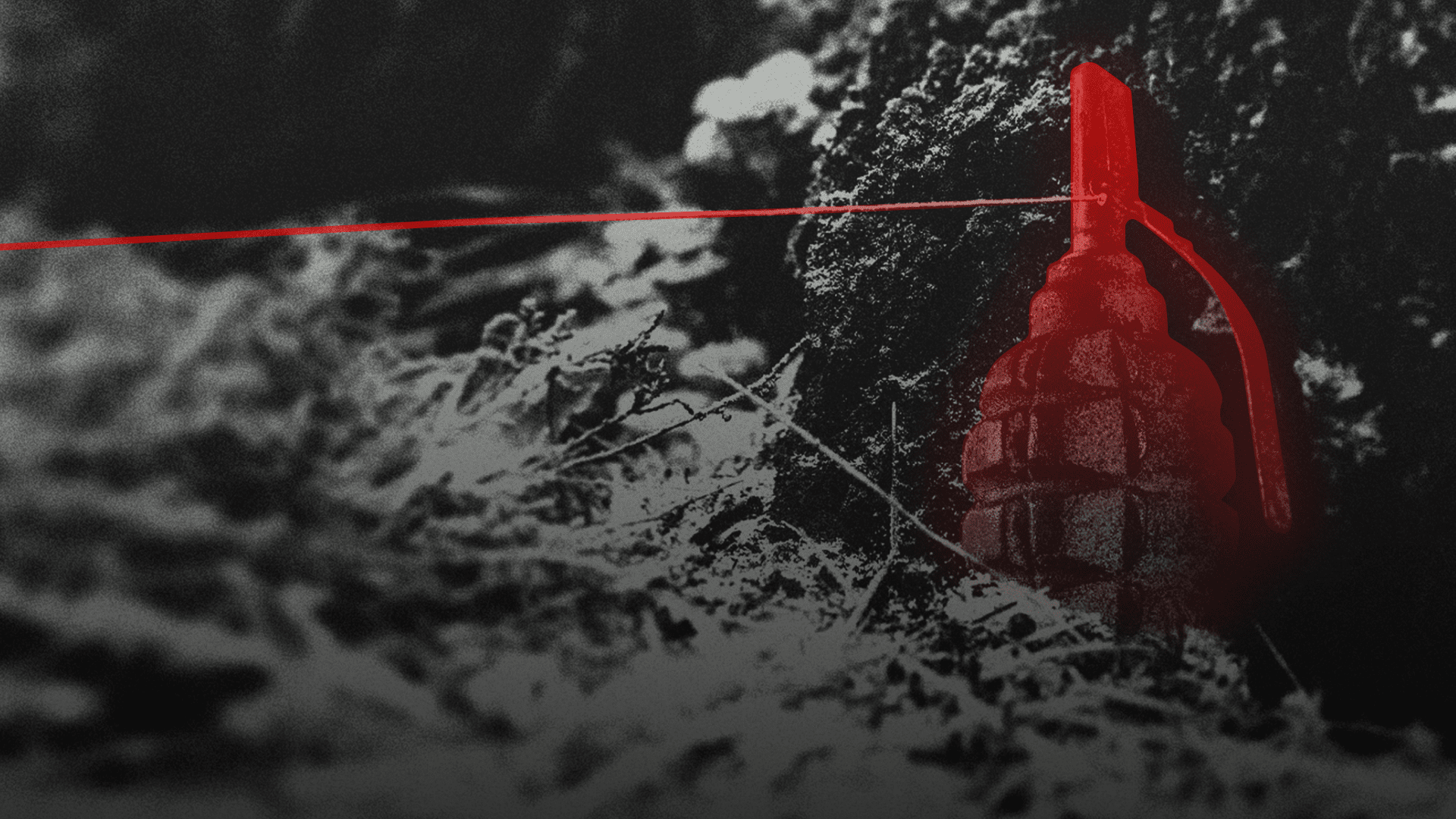

Сluster munitions, though dropped from the sky, often behave like landmines. Their small submunitions scatter widely, and many fail to explode on impact, lying in wait like a mine beneath the soil.

Just moments before, they had been planning dinner. Dmytro had spent the night patrolling the city with the local defense. By day, he helped deliver food to children sheltering underground. That afternoon, they were simply heading home. They didn’t make it those last few hundred meters.

Since 2022, Ukraine has become the most heavily mined country in the world, according to the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS), which reported in April 2025 that millions of explosive devices now contaminate Ukrainian land.

These weapons, hidden in fields, gardens, roads, and homes, don’t just disappear. They remain for years, sometimes decades, long after the fighting moves on, putting the lives of Ukrainians at risk not just today, but for generations to come.

Dmytro survived.

“I flew maybe 30 meters,” he recalls. “I was concussed so badly I couldn’t see anything. My wife—she was in shock, bleeding, but she managed to call the ambulance.”

People were running, panicking. The emergency dispatcher told them no one could come while there was shelling. But someone did. “Two guys came anyway,” he says.

Seeing Dmytro’s leg torn to the bone, the paramedics immediately said he might lose his leg. “But in the hospital, a doctor asked me to move a toe. I couldn’t feel anything, but somehow, I moved it. That gave them a chance to save it.”

He kept his leg. His wife’s injuries healed. But their lives would never return to what they were before that walk home.

Dmytro’s story ends with hope. But not all do. Many victims of mines face permanent disability—if they survive at all.

Learning to live again

There was a flash, then a blow. The explosion happened while Dmytro Slepkan was serving in the State Emergency Service (SES) in the Donetsk region. He was the commander of a pyrotechnic unit.

"It was a sharp explosion, and then I was thrown back and hit the ground," he recalls. After that came a strange sense of weightlessness—like falling through empty space. His memory of those early moments is hazy: voices of doctors, his wife, his mother.

In the first days after his injury, Dmytro still believed his vision might return. "I thought it was temporary," he told me. "That it would all be over soon, that I’d recover and return to life as it was before."

No one told him directly at first that he’d lost his sight. The doctors focused on stabilizing him and carrying out necessary procedures. But as months passed and his condition didn’t improve, reality slowly set in.

“Only in the fourth month at home after the hospital, I realized my sight wouldn’t come back,” he said.

Today, Dmytro works with the Ukrainian Deminers Association, the country’s largest humanitarian demining organization. "Our work focuses on clearing explosives, educating communities, and helping survivors," he explains. It was this very organization that reached out to him shortly after his injury and later offered him a position.

Now, as someone who was both a rescuer and a victim, Dmytro uses his experience to help others navigate the long and difficult road to recovery.

“I just kept living,” he says. “I was a sapper. I used to clear explosives to prevent these tragedies. Now I help the people who live through them. And being one of them myself—that’s what gives me the strength to do it.”

The body and beyond

Coming home should’ve felt like relief. But for both Dmytros, it marked the beginning of something even harder—learning to live in new bodies, with altered rhythms, and the lingering silence of trauma.

For Dmytro Slepkan, the first shock came in his own house.

He’d reach for the tea bag and miss. Try to plug in his phone and stab at empty space. He’d bump into walls, bruise his shoulders, hit his head. Simple things—finding a towel, locating a spoon—suddenly felt impossible.

The hardest part was the helplessness of not being able to do what he used to. The despair would come in waves—after another failed attempt, another bruise. For six months, this was his daily life. Until, little by little, he began to adapt.

“I started to learn how to move through space again,” he said. “To do simple things on my own—that became a victory.”

He began walking with a cane. Then using a screen reader. Then transferring money, paying bills, navigating his phone. The goal wasn’t just survival—it was independence. Rebuilding a life not around what was lost, but what could still be his.

Dmytro Huzhva had a different injury, but the process was similar. Nothing came easily. He dropped from 120 kilos to 56. Months in bed. Several operations. And then, slowly, movement.

Today, he still lives with pain—neck, spine, and headaches. But he works. He walks. He stretches every muscle he can. “You do what you need to do,” he said. “I never give up.”

His wife became his constant, always by his side, even while recovering from her own injuries. Her presence grounded him. Even during the interview, I could hear her voice behind his back.

For Dmytro Slepkan too, family became an anchor. “They always believed in me. From the very first day it happened,” he said.

Support matters

For both Dmytros, family became a lifeline. But recovery rarely happens in isolation. Emotional and practical support—from loved ones, communities, and professionals—can mean the difference between simply surviving and slowly returning to life.

Dmytro Slepkan now channels his experience into helping others. Through the Ukrainian Deminers Association, he offers support to survivors—not only material, but emotional, through presence and careful listening.

“At first, we just talk. Carefully. You don’t want to say too much or say the wrong thing,” he said. “Because beyond the physical trauma, the emotional and psychological wound is just as deep. And early on, every word—even a half-word—matters.”

Sometimes they start interviews. Sometimes they wait. If needed, they connect people with psychologists. The goal is not to push, but to be there. To make sure no one feels forgotten or alone.

“Everyone has their own kind of pain,” he said. “Even if the injuries look the same, the way people carry them is different. It depends on how they see themselves. On whether they have support.”

Support, he believes, is not only therapy or finances. “It’s human. It’s being seen. It’s knowing you’re still part of the world.”

For him, that understanding came with time.

“When I was in the hospital, I heard stories of other veterans who’d gone through it,” he said. “At the time, I thought—that can’t be real. That kind of life after injury felt impossible.”

Now, he speaks publicly, trying to shift the narrative.

“In the media, we mostly see the tragedy—deaths, wounds, losses. But almost never what happens after. How someone lives with that loss. How they manage. Maybe it’s a different life, maybe harder. But they still make plans. They move forward. No pretense. Just real life.”

Dmytro Huzhva remembers those first days, too—when no one really knew what to do after a mine injury.

“There weren’t any clear rules. So I started calling foundations. I asked for help on Facebook. I looked for anything—any resource that could help me get better,” he said.

Some places helped. Others didn’t respond. But he kept trying. “Even small things mattered. I walked. I wrote. I called. I insisted. I didn’t stop.”

-c6522ae9e5320af1cc92504c0aaa1b34.png)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)