- Category

- World

Europe’s Hidden Arsenal: Can France and the UK Forge a True Nuclear Deterrent?

Europe has nuclear weapons—and not just American ones. As France and the UK maintain their independent arsenals, the question now is whether these silent forces can evolve into a collective European deterrent.

Somewhere beneath the cold waters of the Atlantic, nuclear submarines are on patrol—silent, strategic, and unmistakably European.

They belong to France and the United Kingdom, the continent’s only nuclear-armed powers.

Their missions are secretive, their presence rarely acknowledged in public discourse. In Europe, nuclear weapons are something of a taboo—a legacy of the Cold War that many would rather forget than confront.

But they are still here. And as Europe faces a new era of insecurity—with Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, growing fears of US isolationism, and a broader rethinking of defense priorities—the question of Europe’s nuclear future is becoming harder to ignore.

If Washington’s umbrella begins to fold, can the continent rely on its own nuclear assets?

France and the UK have long maintained independent nuclear forces, each shaped by its own strategic logic and political history.

Understanding their current posture and doctrine is a necessary first step in assessing whether Europe is truly prepared for the security challenges ahead or whether it remains strategically dependent.

Inside and outside the NATO framework

The United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent is closely embedded within the NATO structure.

Its four Vanguard-class submarines, each armed with Trident II D5 missiles. At least one UK submarine is always on patrol under posture of continuous at-sea deterrence (CASD).

While the UK maintains sovereign control over its nuclear weapons, it has repeatedly affirmed that its arsenal contributes directly to the collective security of the NATO alliance.

In times of war, British nuclear forces are declared to the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), reinforcing NATO’s nuclear posture alongside US capabilities.

France, by contrast, has always charted a more independent course.

Since Charles de Gaulle withdrew the country from NATO’s integrated military command in 1966 (a decision partially reversed in 2009), Paris has insisted on the autonomy of its force de frappe—a nuclear force designed to defend French sovereignty, not alliance-wide interests.

While successive French presidents have expressed solidarity with NATO, French nuclear weapons are not formally committed to the alliance and are unlikely to be used outside the context of French national defense.

Yet in practice, the line between national and collective defense is increasingly blurred. In a 2020 speech, President Emmanuel Macron offered to initiate a “strategic dialogue” on the role of France’s nuclear deterrent in European security—a proposal that acknowledged growing concerns about US reliability, but which was met with limited enthusiasm from other European capitals.

Macron’s initiative failed not because of a lack of logic—but because of poor timing, said Ukrainian political analyst Mykola Davydiuk in an exclusive interview with us.

“Security is seasonal,” he told me. “When there’s a football championship, no one talks about nukes. But when Russian troops get close to Poland, everyone starts thinking, maybe we do need nuclear weapons.”

In early 2020, the threat didn’t feel immediate enough to trigger serious engagement. For France, it was a step forward. For the rest of Europe, it was too soon. For Ukraine, it was already too late.

And so, while Europe technically has two nuclear powers, in practice, only one, the UK, is meaningfully integrated into a collective defense structure.

What happens if the US pulls back?

For decades, Europe’s security architecture has rested on a foundational assumption: that the United States would be there.

About 100 US nuclear bombs are currently stationed in five European countries—Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Türkiye—under NATO’s nuclear sharing arrangements. These weapons form a critical part of the alliance’s deterrent posture. Alongside them, thousands of American troops, aircraft, and conventional assets help secure the continent from external threats.

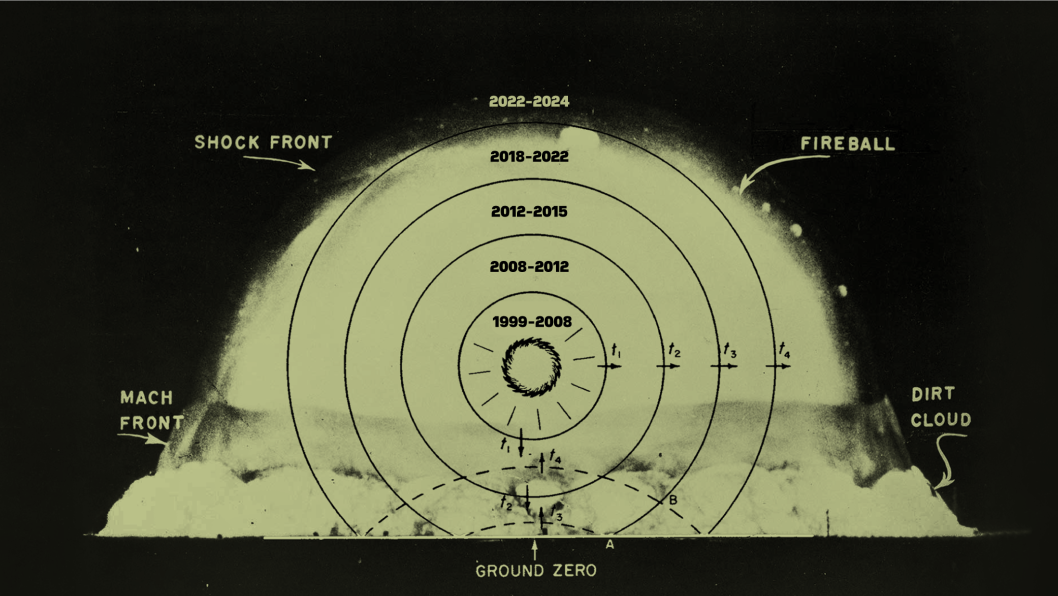

But that assumption is no longer ironclad. In 2016, President Donald Trump openly questioned the value of NATO and mused about withdrawing from it altogether. Even under more traditional presidents, there is growing pressure within the US political establishment to prioritize the Indo-Pacific and domestic concerns over European commitments.

Trump’s signals serve a dual purpose: one of pressure and one of strategy. “On the one hand, it’s a way to shake the alliance—to make partners pay more. On the other hand, it’s a bargaining tool: if allies raise their defense spending, the US might stay,” Davydiuk explains.

When asked whether US disengagement poses a real military threat or remains in the realm of politics, Davydiuk notes: “He’s already pressuring them politically. The big question is whether he’ll move into military disengagement. There’s precedent. Look at de Gaulle—he pulled France from NATO’s military structure but stayed politically. Something similar could happen again.”

In that vacuum, attention would inevitably turn to France and the UK. Could their arsenals, designed primarily for national defense, scale to meet the demands of continental deterrence?

This is no longer a theoretical question, Davydiuk argues. They speak to the heart of Europe’s post-war order and the very real risk that, in the absence of US leadership, that order may need to be rebuilt.

Rethinking the architecture

Some strategists have proposed a more coordinated European nuclear posture, one that leverages the existing arsenals of France and the UK in a collective framework.

This wouldn’t necessarily mean full nuclear sharing in the American sense, but rather a strategic realignment—shared planning, common threat assessments, and perhaps conditional guarantees for key allies. A kind of "Europeanized deterrence" that remains independent but complementary to NATO.

The challenge, however, is not only military but also political.

“Right now, neither France nor the UK is ready to extend their nuclear security beyond national borders,” Davydiuk says. “These are national shields. They won’t just hand over their missiles to Poland or anyone else. It’s not the US model of sharing.”

And yet, the conversation is shifting. This interest in expanded nuclear protection is not limited to Poland. In Germany, long reliant on the American nuclear umbrella, concerns are mounting about the reliability of the US as a security guarantor.

Friedrich Merz, the leader of the Christian Democratic Union and likely the next chancellor, recently called for discussions with France and the UK about the possibility of nuclear protection for Germany. He stressed that Europe must be capable of defending itself independently, especially in the face of a potential US retreat from NATO commitments.

In response, French President Emmanuel Macron expressed openness to discussing the role of France’s nuclear deterrent in European security, noting that France’s “vital interests” have a “European dimension.”

These signals reflect a broader reassessment of Europe’s strategic future. Davydiuk points to an opportunity in the current geopolitical moment: “Europe could use Trump’s rhetoric about rearmament to change the post-WWII rules of the game.”

“We’re entering a decade of chaos,” he says. “Now it’s the law of the strong, not the strength of law. Europe has to become stronger or risk becoming the perfect target: rich, weak, and tempting.”

This doesn’t necessarily mean a return to Cold War arsenals, he notes, but it does require Europe to think seriously about its role, its tools, and its autonomy.

Strategic upgrades

While political discussions about European nuclear deterrence remain cautious, France and the United Kingdom have steadily invested in modernizing their arsenals.

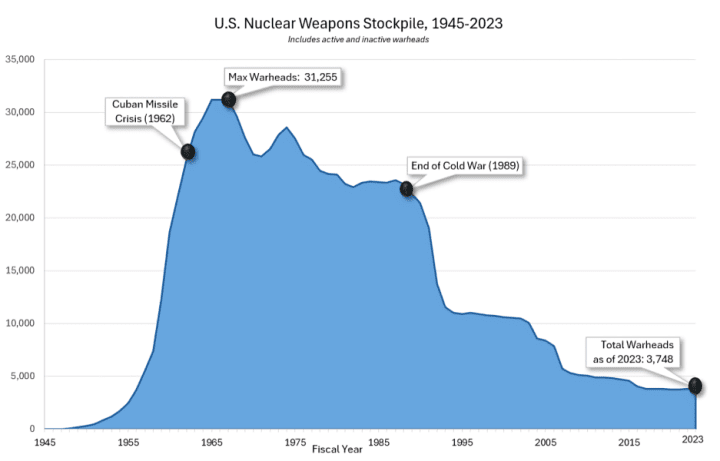

In 2021, the UK announced a significant reversal of its previous policy by increasing its nuclear warhead cap from 180 to 260, citing evolving security threats.

The UK government also allocated billions of pounds to the development of a new class of submarines, the Dreadnought-class, which will replace the current Vanguard-class boats starting in the 2030s. This program, part of the UK’s broader Integrated Review, is expected to cost over £30 billion, with a £10 billion contingency fund.

France, for its part, is pursuing its own long-term nuclear modernization under the “Programme 2030”, which includes upgrades to its Triomphant-class submarines, the development of new air-launched cruise missiles, and improvements to its command-and-control systems.

In 2023, the French Ministry of the Armed Forces allocated over €5 billion for nuclear deterrence, about 10% of its total defense budget.

French President Emmanuel Macron also announced a modernisation of one of the country's main air bases with the latest nuclear missile technology. During a visit to the Luxeuil-les-Bains air base in eastern France on April 29, Macron pledged €1.5 billion in upgrades and confirmed the creation of two new Rafale squadrons, totaling about 40 aircraft.

By 2035, Luxeuil-les-Bains is expected to become the first base to host next-generation Rafale fighter jets equipped with hypersonic nuclear missiles. “The world we live in is increasingly dangerous,” Macron said, urging Europe to defend itself amid Russia’s growing military threat.

More strikingly, Macron has openly suggested that France's nuclear umbrella could extend beyond national borders. According to reports, Paris is considering deploying nuclear-capable jets to Germany—a symbolic signal to Russia and a challenge to Britain to match France’s leadership.

Are two enough?

France and the United Kingdom each maintain what they describe as independent, credible, and survivable nuclear deterrents.

Davydiuk emphasizes that while the UK’s nuclear arsenal is reliable, it lacks strategic weight on its own: “They don’t have the superpower status—submarines are not 5,000 warheads like Russia,” he says, pointing also to the UK’s tight coordination with the United States.

In contrast, France retains more flexibility in its nuclear policy. Thanks to Charles de Gaulle’s legacy, France has “a decent base, more or less comparable to China… for defending Europe, this moderate policy is sufficient,” Davydiuk says.

As of 2024, France possesses approximately 290 nuclear warheads, most of which are deployed on submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), with some assigned to air-launched cruise missiles. The UK maintains around 225 warheads, with up to 120 available for deployment via four Vanguard-class nuclear submarines. In comparison, the United States has a much larger arsenal—roughly 3,700 deployed and stored warheads, with over 1,300 additional warheads awaiting dismantlement.

However, numbers alone don’t shape deterrence. To truly influence the European strategic landscape, both France and the UK would need to elevate their political messaging and take more proactive initiative regarding nuclear security, says Davydiuk.

He also argues that both powers would benefit from openly revisiting past nuclear commitments to Ukraine: “It would be in their interest to talk about maybe returning nuclear missiles to Ukraine. After all, both of them signed the Budapest Memorandum.”

Even symbolic steps in that direction, he suggests, could help unlock stronger military and political support for Ukraine while reaffirming Europe’s own strategic relevance.

For now, French and British deterrents provide a backstop, an implicit floor to European security.

“Russia, even in its war against Ukraine, considered crossing that line, using nuclear weapons. But they were stopped,” he says. “They got the message when Americans warned what would happen if they did. And Russia shelved its missiles. But whether they can anchor a broader European posture in a post-American scenario remains untested.”

-27ef304a0bfb28cb4215e5deede4a665.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)