- Category

- Business

The Video Games to Avoid If You Don’t Want to Support Russia’s War

Fall is here, and with it comes a wave of blockbuster game releases on consoles and PCs. But behind the hype, some of these titles are tied to companies that help bankroll the Kremlin. The question is simple: shouldn’t players know what their money might be funding?

Escape from Tarkov, a popular multiplayer extraction shooter created by Russia’s Battlestate Games, is set for release on Steam, the world’s largest PC gaming platform. The launch comes despite glaring evidence that the studio’s leadership, including head developer Nikita Buyanov, has maintained ties to Russia’s arms industry and associates who joined Moscow-backed forces in eastern Ukraine during Russia’s invasion in 2014.

However, Tarkov is only the most visible example. Other titles—some developed in Russia, others operating through European subsidiaries—continue to profit in Western markets while their creators maintain links to Moscow’s propaganda networks, arms manufacturers, or even combatants in Russian-occupied Ukraine.

Who makes Tarkov?

Battlestate has long cultivated a culture of silence around the war. Its forums and subreddit scrub any mention of Ukraine. Their head developer, Buyanov, disappeared from social media after Russia’s full-scale invasion, reemerging months later without a word on the devastation it caused.

Silence doesn’t constitute neutrality here. Before the full-scale war, Buyanov and his team collaborated repeatedly with Kalashnikov, Russia’s weapons giant, recording promotional videos. He appeared alongside Dmitry “Goblin” Puchkov, a Kremlin-aligned blogger who called for the genocide of all Ukrainians. Other members of Battlestate’s circle openly fundraise for Russian troops and post invasion symbols on their pages.

Battlestate also maintained close ties with the 715 Team, a Kaliningrad-based crew of gun enthusiasts and “tactical trainers” with a massive YouTube following, where Buyanov was a frequent guest. The group built its brand through weapons tests and collaborations with Kalashnikov, but after the full-scale invasion, its leader, Roman “Khors” Chernov, began appearing in occupied Donetsk, declaring support for Russia’s war. At minimum, the crew provided material support in the form of fundraisers for Russian troops, blurring the line between hobbyist content and active participation in the invasion.

#tarkovarena #EscapefromTarkov pic.twitter.com/CmtNo7ijL1

— Escape from Tarkov: Arena (@tarkovarena) December 29, 2022

Their presence bled into Tarkov itself: players on Reddit—among them Georgian YouTuber Gattsu—noted pro-Kremlin graffiti and 715 references inside the game, along with official merchandise tied to the group. For a time, one playable character type in Tarkov was even labeled “hohol,” a derogatory Russian slur for Ukrainians. The overlap between Battlestate’s in-game world and its real-world circle of collaborators shows how deeply entwined the studio became with figures who went from gaming culture to fighting in Russia’s war.

Games that finance Russia’s war

War Thunder

Developed by Gaijin Entertainment, it is one of the most popular military simulators on Steam, with millions of players worldwide. Gaijin insists it is “out of politics,” operating from Hungary as a European publisher. But Ukrainian investigators uncovered a different story. According to Ukrainian military publication Militarnyi, Gaijin bought ad integrations for War Thunder and Crossout on the YouTube channel Krupnokalibernyy Perepolokh, run by Russian blogger Aleksei Smirnov.

Smirnov filmed on occupied territory in Donbas alongside “DNR” fighters, showcasing Russian-supplied weapons, armored vehicles, and even banned PMN-2 anti-personnel mines. His videos, shot at a Russian-backed training ground near Donetsk, doubled as ads for Gaijin’s titles. The revelation means that War Thunder’s publisher wasn’t just turning a blind eye; it was actively financing content produced with Russian militants in occupied Ukraine, giving Moscow’s proxies both visibility and revenue through gaming culture.

Russian blogger Aleksei Smirnov, who filmed a documentary in occupied Donbas, testing Russian-supplied weapons, is listed in Ukraine’s Myrotvorets database as a mercenary.

Even after Russia’s full-scale invasion, Smirnov remained active in the occupied territories. He began posting videos of himself delivering so-called “humanitarian aid” into Mariupol and other cities under Russian control—content that doubled as soft propaganda, portraying the occupiers as protectors. At the same time, the reality on the ground was mass graves, deportations, and destroyed homes.

Atomic Heart

A sci-fi shooter set in an alternate Soviet utopia became one of the most controversial game launches of 2023. Developed by Mundfish, the project drew criticism for its heavy use of communist symbols and its portrayal of a thriving USSR, just as Russia was waging a full-scale war against Ukraine. Ukraine’s Minister of Digital Transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, sent formal letters to Valve, Sony, and Microsoft, urging them to remove the title from their platforms, warning that “money raised from purchases of the game will be transferred to Russia’s budget, so it will be used to fund the war against Ukraine.”

Mundfish denied the allegations and insisted it was a “global studio” based in Cyprus. NBC News reported that it was unable to find proof that sales were directly funding the invasion, but noted that Mundfish’s investors include GEM Capital, a fund tied to a former Gazprom executive, and Gaijin Entertainment, which was founded in Russia. Ukrainian critics like YouTuber Harenko argued the game crosses the line from world-building into outright Soviet glorification, while Deputy Minister of Digital Transformation Alex Bornyakov warned it “romanticizes communist ideology and the Soviet Union.”

Whether Atomic Heart is propaganda by design or by aesthetic accident, the effect is the same: a blockbuster release that launders nostalgia for empire at the very moment Moscow seeks to rebuild one.

Squad 22: ZOV

The most brazen example is Squad 22: ZOV, released on Steam in May 2025 and openly endorsed by Russia’s Defense Ministry. Developed by SPN Studio, the game reframes the invasion of Ukraine as a “liberation” and packages war crimes as playable missions: the first free campaign is the “liberation of Mariupol,” where more than 10,000 civilians were killed, with further missions available for purchase to reenact Russia’s 2014 invasion of Donbas and Crimea. On Steam, the title is advertised as “recommended by the Russian military” for cadet training, and its ZOV branding deliberately echoes the extremist symbols painted on Russian tanks and missiles.

Behind the project is Alexander Tolkach, a former Russian diplomat with a background in behavioral “influence games” and suspected intelligence ties. His work is backed by RVKO, a Kremlin-linked foundation that supports Russian soldiers, raising fears that in-game purchases could funnel directly into the war effort. Ukraine’s Digital Transformation Ministry has demanded the game’s removal, calling it “a tool of war propaganda that should not appear on Steam,” while reviews on the platform have devolved into a propaganda battleground between pro-war users and those condemning it as “Putin’s fever dream.”

Double standards

Steam continues to operate in Russia despite sanctions, allowing Russian players to access and pay for games through workarounds. At the same time, Steam has complied with Russian censorship demands—removing titles or restricting access when ordered by state agencies.

At the same time, in March 2025, Russia’s Internet Development Institute (IRI), which received $275 million in state funding, proposed building a “Steam Killer” for BRICS nations. The platform would push “morality-strengthening” content, censor “destructive” ideas, and even include VR simulators for mobilization training. Officials framed it as a way to set their own cultural standards rather than rely on the West. Few experts think it will work—Steam is simply too dominant. But the proposal shows what’s at stake: Russia sees video games not just as entertainment, but as a strategic domain.

Ukraine’s alternative

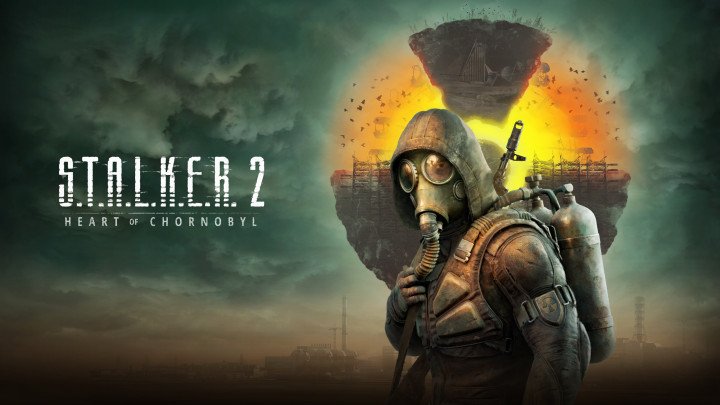

If Tarkov represents the problem, Ukraine’s own game industry represents the alternative. This spring, Ukrainian AAA title S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2: Heart of Chornobyl surged to the top of Steam’s charts just days before release. Developed by Kyiv-based GSC Game World under missile attacks and power outages, the game has already outperformed Call of Duty, FIFA, and other global blockbusters. It will soon be released on PlayStation 5 as well.

The contrast could not be sharper. On one hand, a Russian studio that partners with arms manufacturers and maintains ties to Russian fighters. On the other hand, a Ukrainian studio is building a cultural export under Russian bombardment.

Ethical gaming in wartime

Russia’s war in Ukraine has already forced major publishers to act. Ubisoft, EA, and Rockstar pulled sales from Russia and Belarus. Steam, Epic, and GOG stopped accepting ruble payments. But Russian developers remain adept at evading scrutiny—registering companies in Cyprus, Hungary, or the UK while continuing to sell to Western audiences. Western platforms, eager for content, rarely ask questions.

Though it isn’t just about Tarkov, or Atomic Heart, or War Thunder. Each of these games shows how Russia’s war machine and its propaganda networks can seep into global gaming markets—sometimes overtly, sometimes behind a veneer of neutrality. Steam, PlayStation, and Xbox aren’t just storefronts; they’re distribution channels with the power to normalize or to reject titles tied to a genocidal regime.

Gamers don’t need to be told what to play—but they deserve to know where their money goes. If a purchase props up companies tied to Russia’s war machine or glorifies the Soviet past, that should be clear. What players choose to do with that knowledge is up to them. The fact that so many of these studios and platforms operate in opaque ways is no accident—it’s the only way they can keep the cash flowing.

-270e13af43760897c8cb3e7f3ee9adf1.png)

-b63fc610dd4af1b737643522d6baf184.jpg)

-099180a164f53abb1128c9b5025a2b0e.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-4390b3efd5ecfe59eeed3643ea284dd2.png)