- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Much Has Russia Spent on the War in Ukraine, and Can They Keep It Up?

Russia’s wartime spending is running into a problem: how to maintain record levels of military output as hydrocarbon revenues decline, reserves are depleted, and the budget comes under growing strain.

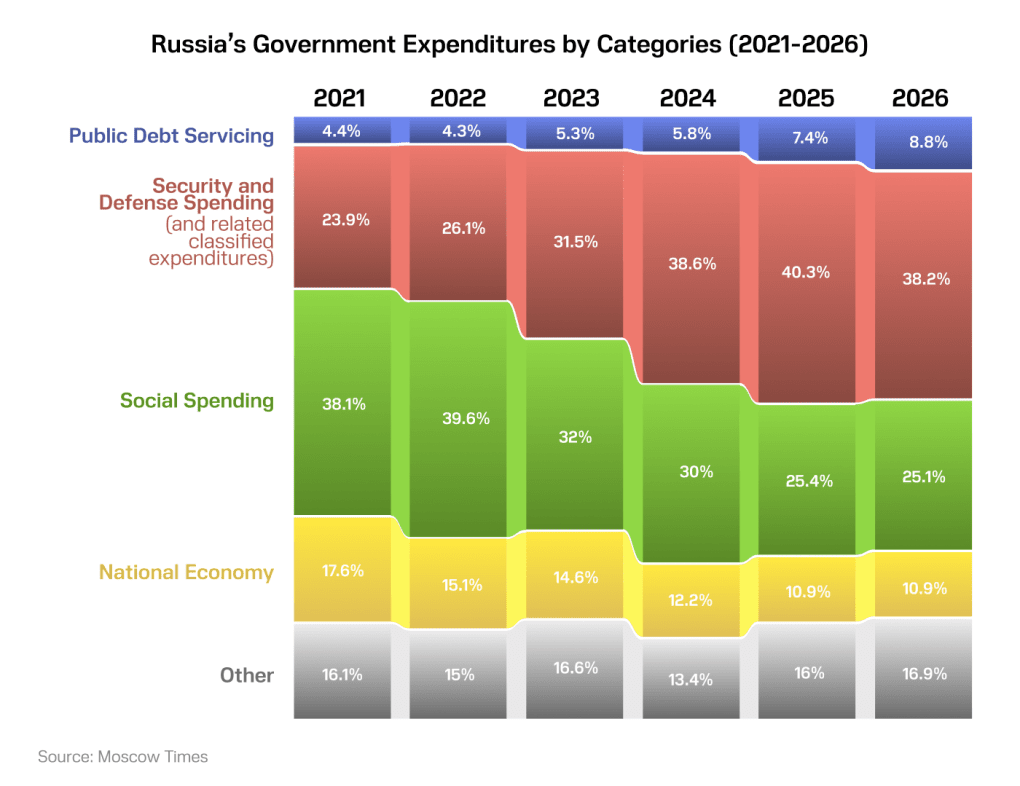

Year after year, Russia has pushed defense spending to levels not seen since the Cold War, even as revenue streams have steadily narrowed. As the war drains reserves and sanctions take effect, the government has begun shifting the burden inward, raising taxes and cutting social spending to keep military expenditures afloat.

We asked economists Yuliia Pavytska of the Kyiv School of Economics and Roman Sulzhyk, a former banker at JPMorgan and Deutsche Bank and a former senior executive at the Moscow Exchange, how long the Russian war machine can operate under these conditions.

Diversification

Russia has financed the war through three main channels: current budget revenues, financial buffers, and, increasingly, domestic borrowing.

In the early stages, it relied primarily on budget revenues, with oil and gas income playing a central role in sustaining cash flow despite European and American sanctions. While energy revenues did not collapse immediately after the invasion, they increasingly came under pressure from price caps, discounts on Russian crude, and declining export margins. As spending grew faster than revenues, the Kremlin began drawing on financial buffers, particularly the liquid cash and gold held in the National Wealth Fund, to cover widening budget gaps.

That model is now under strain, as depleted reserves and significantly weaker oil and gas revenues have pushed the Kremlin toward financing the war by raising taxes on Russian households and businesses, and central bank support, explained Pavytska

Information published by The Moscow Times shows that Russian leader Vladimir Putin has approved a 2026 budget that locks Russia into a wartime economic model. Total government spending is projected at roughly 44.1 trillion rubles, equivalent to about $440–550 billion depending on the exchange rate used. Nearly 40 percent of that spending, 16.84 trillion rubles ($166.8 billion), is directed to the military and security services, while allocations for social programs and the broader economy fall to multi-year lows.

The shift is now visible in the budget itself. For the first time, Pavytska said, Russia is financing the federal budget mainly by borrowing rather than relying on surplus revenues or reserves, with a planned deficit of 5.6 trillion rubles (roughly $56 billion). Although the Finance Ministry managed to hit its official deficit target, she said this was likely achieved by cutting or delaying spending at the end of the year. That, she warned, should not be seen as a sign of stability, as overall spending remains at record levels and budget pressures are expected to worsen as energy revenues fall.

How much has Russia spent?

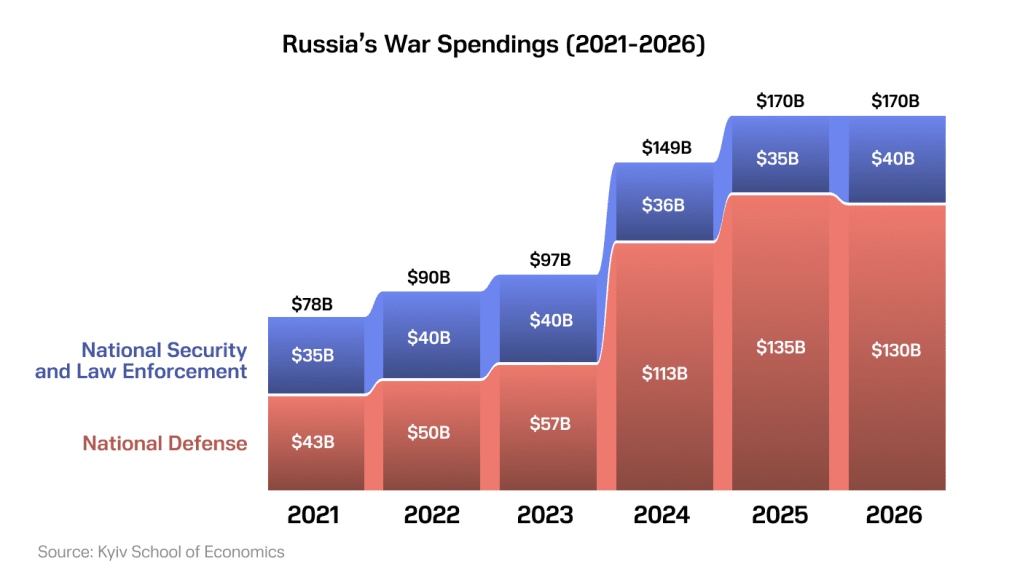

Using official Russian budget figures compiled by the Kyiv School of Economics, Russia allocated at least 50.6 trillion rubles to military and security spending between 2021 and 2025. Adjusted for annual exchange rates, this amounts to roughly $580–600 billion. These figures represent a lower bound, based on publicly reported spending on National Defense and National Security.

The estimate excludes classified budget items and other off-book war costs. “Russia does not fully report how much it is actually spending,” Pavytska said, adding that total war expenditures are likely significantly higher than what appears in official budget figures.

Spending was already elevated before the full-scale invasion. In 2021, Russia allocated about 5.6 trillion rubles ($75–80 billion) to military and internal security, a level that carried into 2022 and rose modestly to 6.3 trillion rubles ($90–95 billion) in the first year of the war. That spending reflected what Moscow believed a short campaign would cost: an operation centered on occupation and regime change, expected to last days rather than turn into a prolonged war of attrition, and met with only a limited response from the West.

-4a231d1d99053f64a758529c488b327d.jpg)

Instead, Ukraine fought back and Western countries began financing its defense, driving costs sharply higher for Russia as the war dragged on. Combined military and security spending reached 8.5 trillion rubles ($95–105 billion) in 2023, before jumping to 13.7 trillion rubles ($145–150 billion) in 2024. The increase was driven by near-total wartime weapons production, higher pay and bonuses for soldiers, compensation payments to families of the dead and wounded, and the mounting logistical burden of sustaining a large force along the front.

By 2025, military and security spending was set to reach 16.5 trillion rubles (approximately $165 billion), accounting for nearly 40 percent of the federal budget. Projections for 2026 push that figure slightly higher, to around 16.8 trillion rubles, or roughly $165–170 billion, locking Russia into a wartime budget that shows no signs of being rolled back.

Russia is no longer paying for the war with excess cash. It is now financing the war through borrowing and internal reallocation, pushing strain deeper into the federal budget, Pavytska said.

How long can Russia keep paying for the war?

In the short term, the answer is: longer than many expected, but not indefinitely. Pavytska says the current budget framework suggests Russia can sustain military spending at roughly its present level for another one to two years, assuming no major external shocks. “But it is becoming harder each month,” she said.

This outlook depends heavily on oil prices, sanctions enforcement, and the government’s ability to continue borrowing domestically without triggering broader economic instability, she said.

A key constraint is the depletion of reserves. The liquid portion of Russia’s National Wealth Fund has fallen by more than half since early 2022, sharply limiting the state’s ability to plug budget gaps with savings. “They are entering this year in a much weaker position than before,” Pavytska said. “The buffers that allowed them to absorb shocks in the first years of the war are largely gone.”

That analysis is echoed by Sulzhyk, head of the Ukrainian defense fund Resist.UA and a former senior executive at the Moscow Exchange. Sulzhyk said Russia’s ability to sustain the war so far has rested less on financial ingenuity than on steady export revenues and pre-war cash reserves, both of which are now under pressure.

“They had roughly $250 billion in liquid reserves at the start of the war, and those are effectively gone,” Sulzhyk said. “That cushion allowed them to absorb early shocks. Now they will feel every shock.”

Russia has been burning through hard-currency buffers at a rate of $75–100 billion per year to support the war and stabilize the economy, Sulzhyk estimates.

Borrowing time

“What props Russia up is not accounting tricks,” Sulzhyk said. “It’s oil and gas revenue. If that falls meaningfully, the system starts to crack.” Even a moderate drop in export revenues could make a serious impact now that there is no reserve buffer left, he says.

In a Russian city, a woman sarcastically mocks a wretched bus, comparing its state to the Russian “Oreshnik” intermediate-range ballistic missile. pic.twitter.com/ZWwMUHF1WC

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) February 1, 2026

Both analysts agree that domestic borrowing can keep the system running for now, but at a growing cost. Russia is increasingly financing the war by borrowing at home, with the central bank ensuring the government can continue issuing debt even as borrowing costs hover around 16%.

Pavytska said this allows the government to maintain military spending in the short term but increases inflationary pressure and limits future policy options. “This is not a sustainable model indefinitely,” she said. “It buys time, not stability.”

This Russian woman says that the war against NATO is more important than repairing hospitals. pic.twitter.com/XkG3Bt8YrV

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) January 29, 2026

Sulzhyk was more blunt about the long-term outlook. “They have tremendous resilience, but it’s not infinite. The probability of a serious financial break is higher now than it was a year ago, but it’s still not guaranteed.” He estimated the risk of a major financial crisis in 2026 at 10 to 20 percent, noting that Russia has a high tolerance for economic pain and a population accustomed to declining living standards.

For now, both experts agree on one point: Russia can continue fighting at roughly the current intensity through 2026 and likely into 2028, but only by accepting rising economic strain and steadily worsening civilian conditions.

“They will always try to find money for war,” Pavytska said. “The question is how much damage they are willing to tolerate elsewhere in the economy to do it.”

Why sanctions have not broken Russia’s war finances

Sanctions have increased pressure on Russia’s economy, but they have not shut down the mechanisms that fund the war. Both Pavytska and Sulzhyk point to the same core weakness: weak enforcement makes sanctions evasion relatively easy and, in many cases, highly profitable.

During his speech today in front of the 56th Annual Summit of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky criticized Europe for its inability to properly defend against or punish Russia, specially stating, “Europe loves to discuss the… pic.twitter.com/YvbYXYo6em

— OSINTdefender (@sentdefender) January 22, 2026

Russia has adapted quickly by rerouting trade through third countries and intermediaries. Critical components, including electronics used in weapons systems, are often purchased legally by shell companies and then resold into Russia with minimal oversight. “It is extremely low risk and very high reward,” Sulzhyk said. “You can sell sanctioned goods through intermediaries, make enormous margins, and the chances of getting caught are still very small.”

This, he says, has created a parallel supply chain in which companies can plausibly deny responsibility for where their products end up. “A reseller can say they sold to a company in Türkiye or Central Asia, and that’s the end of the paper trail,” he said. “There is no real incentive to ask where the goods actually go.” As a result, sanctions on technology and equipment have slowed Russia down and made it more expensive, but have not stopped it from sustaining military production.

Energy revenues remain the larger issue. Before the war, Russia earned roughly $230–300 billion a year from oil and gas exports; despite price caps and shipping restrictions, it is still bringing in an estimated $180–200 billion annually, often at a discount. That income has been enough to keep the budget afloat and soften the impact of sanctions, particularly in the early years of the war.

As long as oil and gas revenues continue, the Kremlin retains the ability to finance the war, even as financial pressures mount elsewhere, Pavytska says.

Feeling a little exposed

Where both analysts see potential leverage is in tightening enforcement rather than expanding sanctions lists. Sulzhyk argued that penalties should extend beyond direct exporters to include resellers and suppliers further up the chain. “If a sanctioned product ends up in Russia, responsibility should not stop at the last company in line,” he said. “Everyone involved should face real consequences. Otherwise, the system will keep working.”

It is in that context that Sulzhyk argues for mandatory disclosure by Western companies still operating in Russia. Publicly traded companies are already required to report how much they’ve paid in taxes to foreign countries; however, Russia is one of the few places where that information often remains opaque.

Applying the same rules, Sulzhyk said, would be a practical step, requiring transparency on which firms are still contributing to the Russian budget and giving investors and regulators a clearer picture of who continues to support the war economy.

Tougher enforcement and more transparency would matter far more now than they did at the start of the war, Pavytska said. With reserves mostly gone and borrowing replacing savings, Russia has less room to absorb shocks. The system is still running, she said, but it is much more vulnerable than it was in 2022.

The system may still be functioning, but analysts say it has become more exposed to pressure. While sanctions have limited prices and access to finance, weak enforcement has allowed Russia to continue exporting energy and earning revenue. At the same time, Ukraine has increasingly targeted oil infrastructure, and Western authorities have begun detaining vessels linked to Russia’s shadow fleet, both of which have proven to have a cumulative effect on Russia’s bottom line.

-457ad7ae19a951ebdca94e9b6bf6309d.png)

-19428fefbe2e33044463541807f3be57.jpeg)

-a6234ca475e2ff3b65e041f9235b512b.jpeg)

-048987b1cb8d32e4786971ae6cd0f55f.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)