- Category

- War in Ukraine

The Russian Monster Built on Oil and Loopholes is Already Choking

“They don’t care how many people in Ukraine are being killed by the Russian War Machine,” US President Donald Trump said, naming the brutal reality: Moscow’s war machine is grinding on, but that machine is starting to buckle under pressure.

Ukraine is the frontline force dismantling Russia’s war machine every day on the battlefield. But this machine isn’t just tanks and missiles. It is powered by oil revenues, smuggling routes, foreign labor, and even Western technology slipping through sanctions.

Ukraine and its allies have slowed it, but it’s far from over. Tightening sanctions and cutting re-exports could finally halt Moscow’s relentless attacks. Experts at the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) confirm: with urgent Western action, Russia’s war machine can be fully dismantled.

⚡️ US Senator Graham: Now it’s time for our European allies to step up and pull their weight.pic.twitter.com/eWxVpyeDuq

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) September 14, 2025

The anatomy of Russia’s war machine

Russia’s war machine is a sprawling network of economic, industrial, and political enablers that keeps the Kremlin grinding forward in a war of attrition. At its core is oil money: every barrel sold abroad fuels tanks, drones, missiles, and soldiers on the front lines.

The military-industrial complex (MIC) is centralized and dominated by Rostec and state conglomerates that monopolize production. Feeding it are Western parts smuggled through sanctions evasion, foreign labor, and an economy fully bent toward war.

But—underneath—the system is inefficient, dependent on foreign tech, labor-starved, and burning through reserves. It’s more about sheer mass and money than innovation or sustainability. Every Ukrainian strike on Russian oil refineries and every Western sanction chips away at its capacity.

Russia has turned its economy into a war engine, with shadow logistics networks and imports from China, Iran, and North Korea filling gaps in ammunition, drones, and shells. But this machine cannot run forever. Ukraine is dismantling it piece by piece, proving that what looks unstoppable is, in reality, a giant on life support.

To dismantle it fully, Western allies must act: cut off oil revenues, tighten sanctions, seize assets, block tech transfers, and support Ukraine’s strikes and defenses.

Unity between the United States, the European Union, and the countries of Europe is very necessary. We need this unity to achieve peace, and I think that only together, the United States and Europe can really stop Putin and save Ukraine.

President of Ukraine

Russia’s economy, fuelling its war machine

Russia, despite spanning one-sixth of the globe, runs an economy smaller than the UK and ten times smaller than the EU. The Kremlin plans to boost defense spending to $141 billion in 2025 but faces a record deficit as reserves—built up over the past 15 years—could be depleted as early as this year.

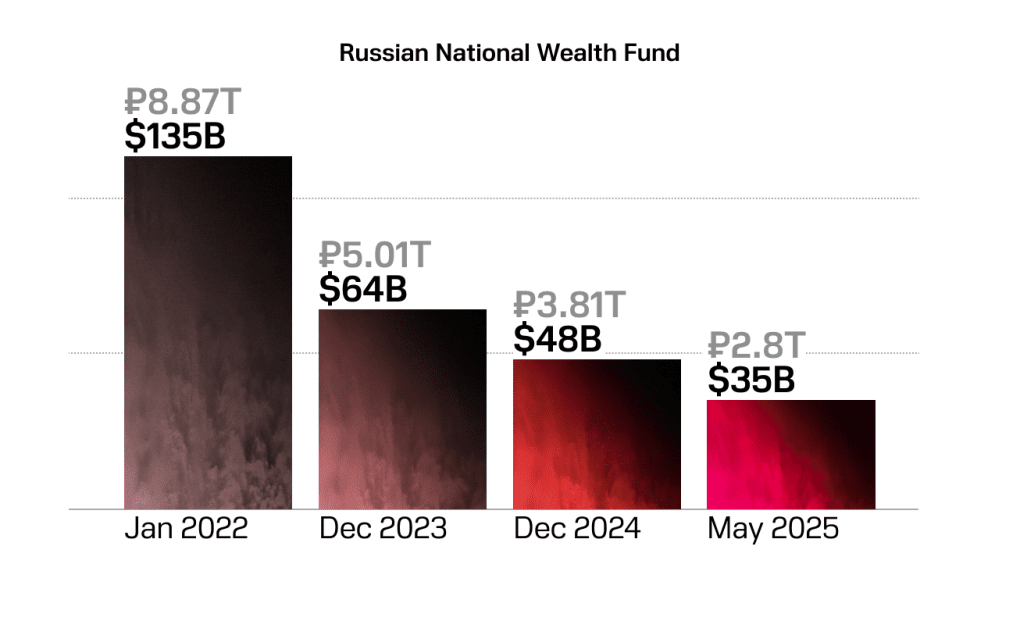

National Wealth Fund

The National Wealth Fund (NWF)—Russia’s main financial cushion built from oil and gas profits—has been drained from $185 billion in December 2021 (over 10% of GDP) to just $30 billion by March 2025, as the Kremlin diverts it to expand the military-industrial complex and finance the war in Ukraine.

Oil and gas revenues fund infrastructure projects, while the NWF plugs budget shortfalls. When oil prices are high, a portion of excess revenue is taxed and funnelled into NWF.

Oil and gas revenues

Despite sanctions, Russia still rakes in billions from oil and gas, which fund around 40% of the defense budget and serve as the country’s main source of foreign currency.

Russia controls over 10% of global oil exports, with revenue from sales fueling the military-industrial complex, from drone factories in Yelabuga to troops on the front lines in eastern Ukraine.

Oil and gas earnings keep ammunition flowing, modernize weapons production, and bankroll the search for mercenaries worldwide. This energy dependence keeps Putin’s war machine running—but it is also his deepest economic vulnerability.

China and India buy 80% of Russia’s crude, giving Moscow a financial lifeline while offering those countries discounted energy and a competitive edge. However, from August 1, 2025, a 25% tariff on Indian goods was imposed, with Trump warning of an additional 25%, bringing the total to 50%. Continued cooperation with Russia, especially in the oil trade, could now carry more risks than benefits for many countries.

⚡️ Zelenskyy: It is necessary to reduce the consumption of Russian oil, and this will definitely reduce Russia's ability to fight. pic.twitter.com/0qodql9Cos

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) September 13, 2025

Mounting economic strain

Ukraine has targeted Russia’s oil dependence. In August 2025 alone, Ukraine reduced Russia’s refining capacity by roughly 17%—fueling tanks, artillery, and transport. Gasoline prices hit a record 77,000 rubles ($1,000) per ton, with retail costs up 8% since early August. On August 1, 2025, Moscow banned fuel exports to non-CIS states and may extend the ban to allies. Companies could also be forced to sell 17% of output domestically, up from 15%, squeezing export profits.

Rising pressure from falling oil prices and sanctions is forcing Russia to drain the National Wealth Fund, while local authorities have been forced to introduce ration cards. Belarus is seeking to pivot from exporting fuel to Russia, instead, exporting to China, India, and Africa—just as Russia struggles most.

The war costs $142 billion this year alone, with over one million troops killed over the last three years. Every dollar stripped from Russian oil revenues is a dollar less for weapons. Limiting these funds doesn’t just support Ukraine—it directly constrains Moscow’s ability to finance further aggression.

The key players behind Russia’s military industry

Russia’s war machine is dominated by a handful of state-linked corporations. Of total assets, 52% sit within the top ten, including Rostec, Almaz-Antey, KTRV, Roscosmos, and Rosatom, highlighting deep government control.

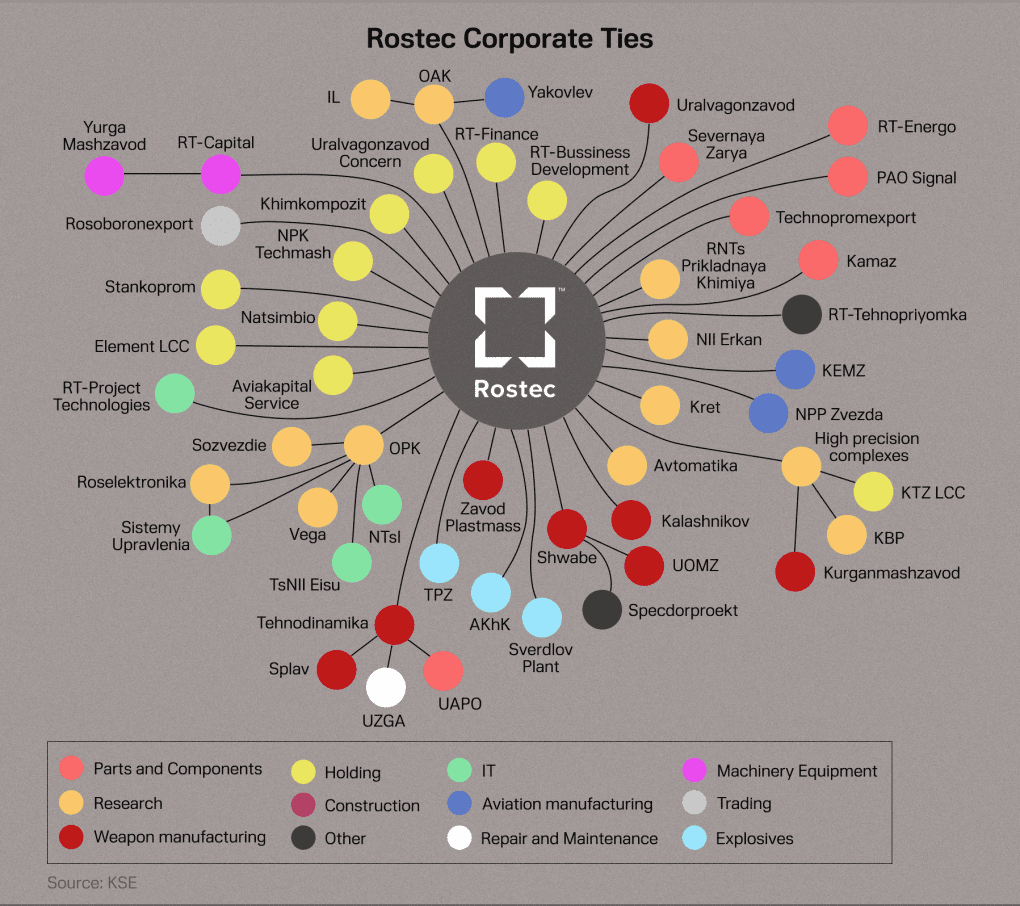

Rostec

State-owned Rostec alone oversees 800+ companies across twelve sectors, monopolizing war contracts and most of the military-industrial complex’s output. Led by Putin ally Sergey Chemezov, Rostec has expanded into Ukraine’s temporarily Russian-occupied territories, Donetsk and Crimea, controlling roughly 90% of military production across Russia and funneling nearly half of Russia’s procurement through its networks.

Rostec also works with sanctioned firms: in February 2025, one subsidiary secured $7.4 million in US and German equipment to boost electronic warfare capabilities, showing how it continues to source critical technology despite restrictions.

Rosatom

Russia’s state-run nuclear giant, Rosatom, controls the country’s entire nuclear infrastructure and supplies missile fuel to the military, making it a direct enabler of the war in Ukraine. Its entities design submarine reactors, produce nuclear weapons, and manufacture pure uranium, linking civilian and military operations.

Since March 2022, Rosatom has been involved in the occupation of Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, reportedly aiding abductions and torture of staff and local residents—showing its influence extends beyond energy.

Despite this, Rosatom itself remains unsanctioned, with only select subsidiaries and senior executives targeted, allowing it to continue fueling Moscow’s war efforts.

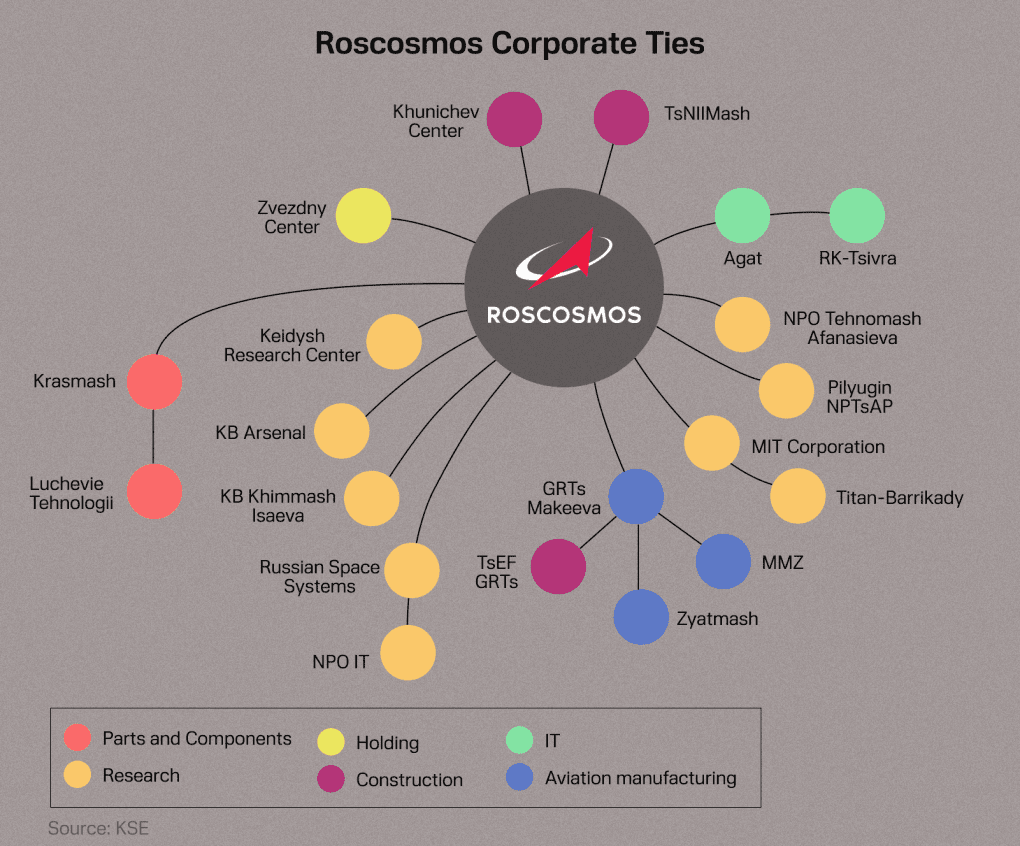

Roscosmos

Russia’s state-run Roscosmos oversees a vast network of subsidiaries that feed Moscow’s war machine, producing submarine-launched ballistic missiles, guidance and navigation systems, and missiles of all ranges—from tactical to intercontinental.

Previously bound by public procurement rules, in 2024 the State Duma allowed Roscosmos confidential contracts to shield it from Western sanctions, KSE reports.

While some subsidiaries face EU and US sanctions, Roscosmos itself remains untouched, continuing to supply critical technology to Russia’s war machine.

Russia’s war machine supply routes

Russia’s military-industrial complex runs on imported brains and machines, relying heavily on foreign-made parts, materials, and technology. Western sanctions have slowed it in some areas, but they have not paralyzed the system.

Through smuggling routes, shadow supply chains, and ramped-up domestic production, the Kremlin keeps its war machine moving. These examples represent just a fraction of Russia’s ongoing foreign procurement efforts.

Electronics and semiconductors

In 2023, over $5 billion in EU shipments, including sanctioned dual-use goods, never reached their intended destinations in Central Asia and the Caucasus. These goods—ranging from drone software and engines to encryption devices—are meant for civilian use but are repurposed for Russia’s military.

Microelectronics from sports watches end up in drones, and semiconductors from dishwashers and refrigerators in missiles. Civilian use of dual-use goods allows these items to be rerouted to Russia despite sanctions.

Russia also exploits online suppliers: a US-based distributor, Texas Instruments, shipped over 4,000 orders worth $6 million in the first eight months of 2024, with nearly $4 million going directly to weapons manufacturers.

Machine tools and equipment

Between January 2023 and July 2024, Russia imported $18.2 billion in CNC machines and components, essential for producing high-precision defense parts. While China leads as a supplier, EU countries like Germany, Italy, and Switzerland still provide equipment via third-country intermediaries—over 10,000 CNC machines worth $403 million and $1.1 billion in components reached Russia.

A Czech company funneled $22M in high-grade metallurgy and engineering goods through Türkiye, including EU-restricted materials vital for Kalibr, Iskander, and Kh-101 missile engines.

Bearings, tiny but critical for tanks, drones, and missiles, also flow from the EU and Japan despite sanctions—tens of millions of dollars’ worth. Sweden’s SKF officially exited Russia but remains a top supplier; Czech firm ZKL admitted selling its goods to Russia, via China. These items continue turning up in Russian weapons on the battlefield.

Materials

The Iskander-M ballistic missile, one of Russia’s deadliest weapons against Ukraine, depends on imported materials for its fuel. A key ingredient, sodium perchlorate, is sourced mainly from China and Uzbekistan after the EU cut supply.

However, exports of sodium chlorate, its precursor, are still not fully banned in the EU for export, re-export, or transit through EU countries.

Russia holds vast titanium reserves but imports 96% of its raw supply, mainly from the EU. Titanium powers missiles, warplanes, and engines. In 2022, the EU bought $365 million of Russian titanium, much for Airbus and Boeing.

-4c14bcf05599d267050b9396ccd717de.jpg)

Meanwhile, Rosatom’s Chepetsk Mechanical Plant, unsanctioned, expands titanium production for warships and aircraft, keeping Putin’s titanium lifeline alive.

Russia’s missiles may strike with steel and fire, but their power begins with cotton pulp. The country’s ten gunpowder plants, including Tambov, which has been hit multiple times by Ukraine’s precision strikes, produce 200 types of propellants for the war machine.

Ukraine sanctioned Russia’s key supplier, Rustam Muminov, an Uzbek-British national. Yet cotton pulp continues to fuel Russia’s missiles. Since 2022, Muminov has shipped over $170 million in cotton pulp to Russia. Controlling 85% of Uzbekistan’s exports, he supplies the raw material for nitrocellulose, the same substance used at the Tambov Plant to produce explosives for Russia’s weapons—keeping Putin’s missiles flying.

Russia’s foreign labor recruitment

Russia’s full-scale invasion has occupied less than 1% additional territory since its full-scale invasion began. Instead, the Kremlin relies on waves of drone attacks to wear down Ukraine’s air defenses and terrorize civilians. This wouldn’t be possible without equipment from its allies and a supply of foreign labor.

The military-industrial sector employs 4 million people, which is more than the population of some NATO countries, the Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Centre (USCC) reported. Even so, Russia’s State Duma claims a shortage of up to 400,000 people in the defense industry.

-b6ee4c6cf1e1afa682f60551181f4534.jpg)

Factories like Alabuga, producing 5,760 Shahed drones in the first nine months of 2024—double 2023 output—have doubled staff to 25,000, USCC reported, relying on underage students and foreign recruits, mostly young women from Africa, via the ‘Alabuga Start’ program.

Russia also recruits abroad: Rossotrudnichestvo, also known as Russian House, in the Central African Republic is actively sourcing labor, while a 2025 deal with Uzbekistan aims to bring in 10,000 workers; 1,150 Uzbeks are already employed. Russian House branches have not yet been sanctioned and continue to operate, even in Europe, keeping the workforce pipeline open.

How to take down Russia’s war machine

Sanctions hit Russia, but the war machine keeps turning

Russia is the world’s most sanctioned country, with EU trade and financial restrictions in place since 2014. While sanctions have slowed some operations, they haven’t fully dismantled the Kremlin’s war machine, forcing Moscow to exploit loopholes and evasive channels.

Sanctions on Russia has published a chronological overview of the main sanction packages imposed by Western allies alongside Russian countermeasures.

Sanctions are not a one-off action; they are part of a dynamic power struggle. It’s an economic arms race: the moment one loophole is closed, new ones are discovered. The EU and its allies must continuously tighten and refine their tools.

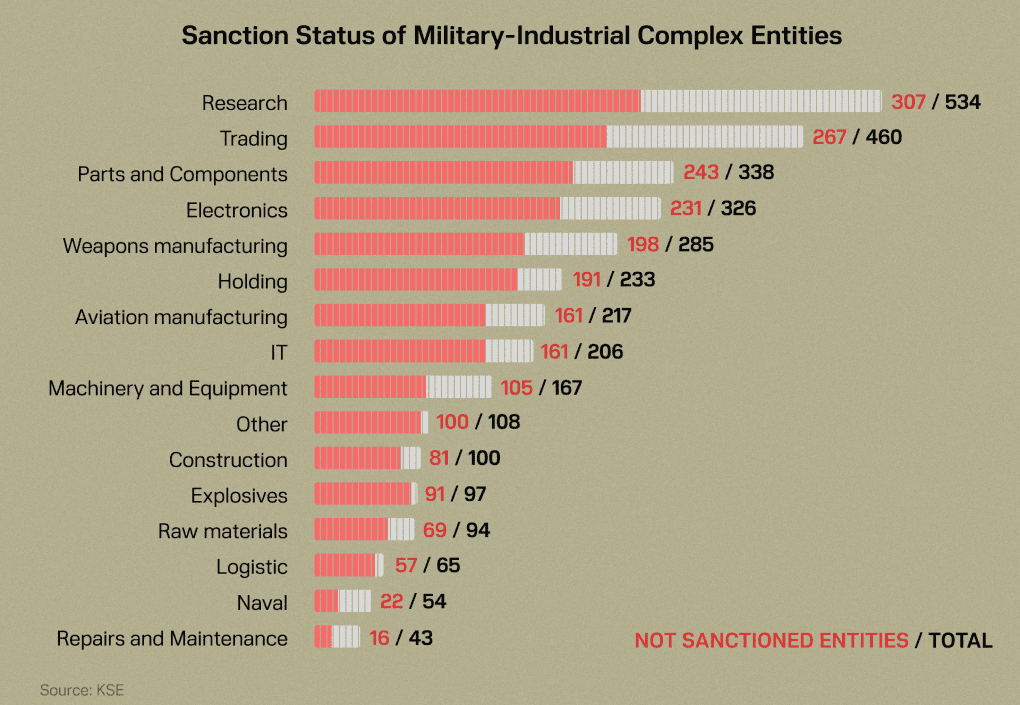

Many entities in Russia’s military-industrial complex remain unsanctioned, including most under Rosatom and Rostec. Only 37 of 85 Rostec companies are sanctioned, despite their key role in weapons production. KSE reported that there are many examples of a misalignment between companies’ roles in the MIC and missing sanctions coverage.

Weapons manufacturers are most likely to be sanctioned, but despite desires to crack down on dual-use goods shipments to Russia, the West has partially failed to sanction the very entities that purchase these dual-use goods for military ends, KSE added.

The EU’s 18th sanctions package, announced July 18, 2025, targets oil revenues, banks, and trade routes used in evasion. The 19th package, expected by September 2025, aims to close remaining gaps.

As Russia adapts its circumvention methods, the latest package focuses on ensuring that existing sanctions are effective. It targets oil revenues, the banking system, and trade routes that have been used in sanction evasion.

On August 20, 2025, the UK government targeted Kyrgyz financial networks and crypto channels used by Russia to fund its war. The UK also targeted Kyrgyz financial networks and crypto channels, which were found to move $9.3 billion in just four months for Russian military funding.

If the Kremlin thinks they can hide their desperate attempts to soften the blow of our sanctions by laundering transactions through dodgy crypto networks–they are sorely mistaken.

Stephen Doughty

UK Sanctions Minister

Since Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine began, Kyrgyzstan has had a growing re-export trade, which has been actively helping Russia evade sanctions. In 2021, Kyrgyzstan imported just €230 million worth of goods from EU countries. By 2022, that number had quintupled to €1.2 billion. The trend continued, with imports nearly reaching €2.8 billion in 2024.

The country imports cars, spare parts, medical equipment, and many other high-quality goods from the EU—products far beyond the reach of ordinary Kyrgyz citizens. Since direct shipments are blocked by sanctions, the vast majority of these imports are then re-exported to Russia.

Russia’s arms export revenue is plummeting

Despite its militarized economy, Russia’s Rostec revenues plummeted sharply after the 2022 full-scale invasion due to sanctions, losing its most profitable activity: arms exports. Rostec reported a 60%+ decline in exports from 2022 to 2024, as domestic demand dominated.

Russia’s arms exports plunged 92% between 2021 and 2024:

2021: $14.6B

2022: $8B (-$6.6B)

2023: $3B (-$5B)

2024: $1B

Many traditional buyers have turned to China, leaving Moscow dependent on a handful of strategic clients like India, China, and Myanmar. The Kremlin has even been forced to buy back Russian-made weapons and spare parts from foreign purchasers, CSIS reported.

Seizing assets could fund Ukraine and cripple Moscow

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion, an estimated $290–330 billion of its assets in Western countries have been frozen—nearly equal to global support for Ukraine at just under $301 billion, the Kiel Institute for War Economy reported.

EU institutions continue to debate how to legally unlock these assets. Many governments remain cautious due to legal and financial risks, but momentum is building for more assertive action. “Using Russian rather than Western taxpayer resources is both morally and politically compelling,”Free Network stated.

Frozen assets limit Moscow’s ability to fund the war and cushion sanctions shocks. Russia is already running wartime deficits via its National Wealth Fund. Seizing assets would raise the cost of war, forcing higher domestic taxes and cuts to non-military spending.

In April 2024, the Council of Europe unanimously adopted Resolution 2539, which called for states to seize assets of Russian politicians, oligarchs, and war collaborators. On July 9, 2025, the European Parliament passed a resolution urging EU states to redirect frozen Russian funds into Ukraine’s defense and reconstruction, holding Moscow accountable for the invasion.

Russia must be held accountable and pay reparations for the destruction it has caused in Ukraine.

European Parliament

The West must finish dismantling Russia’s war machine

Sanctions have crippled Russia’s war machine, cutting access to Western components, draining the National Wealth Fund, and exposing reliance on foreign microelectronics, metals, and propellants. Factories slow, missiles lack chips, and supply chains buckle under disruption.

Yet the Kremlin’s military-industrial complex still turns, fueled by intermediaries, dual-use goods, and loopholes. To truly stop Moscow, the West must tighten choke points, close re-export gaps, and cut every lifeline feeding its weapons.

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-347244f3d277553dbd8929da636a6354.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)