- Category

- Culture

Inside Paris Photo 2025: Ukrainian Photographers Claim Their Space on the Global Stage

At the Grand Palais this week, amid the international throng, Ukraine will very much be present—not quietly, not apologetically, but with a persistent, urgent visibility.

From the polished floors of Galerie Alexandra de Viveiros, based in Paris but operating as a “nomadic” gallery, to the curated program of Carte Blanche Students, Ukrainian photographers claim space for their vision, their histories, and their silences.

Ukrainian photographers shine at Paris Photo 2025

Elena Subach, a Ukrainian photographer born in Sheptytskyi in 1980 and now based in Lviv, studied economics before she put her eye to a lens.

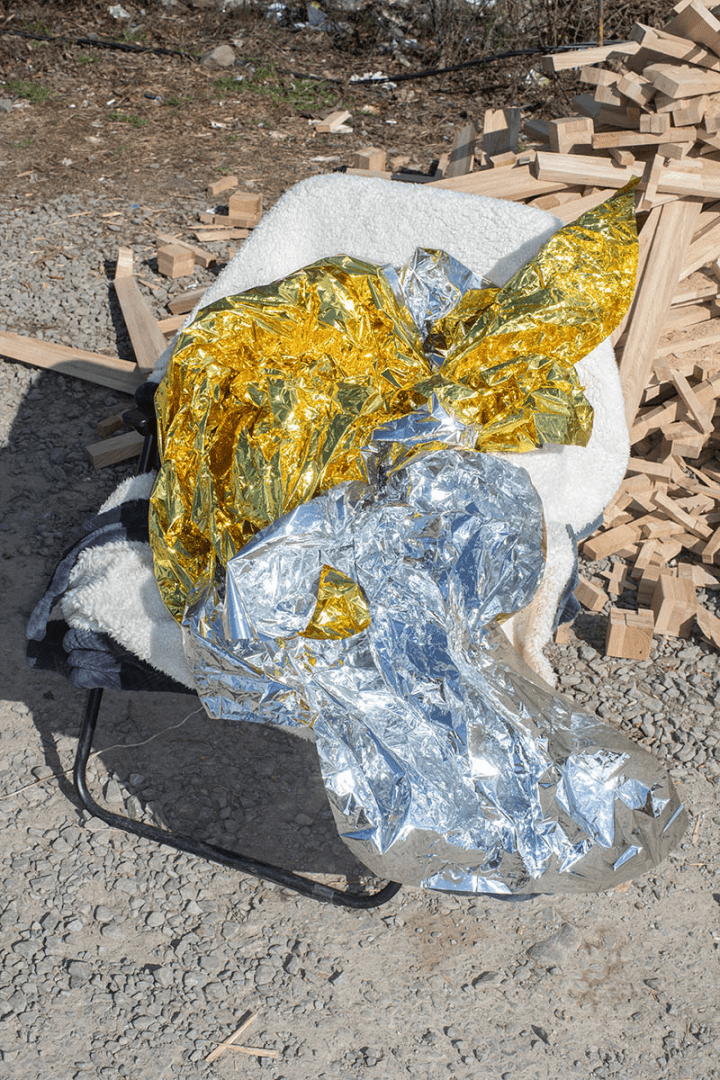

Her work deals with fragility, with bodies, with the weight of history and its violent erasures. At Paris Photo 2025, Galerie Alexandra de Viveiros presents her series Hidden, made in spring 2022.

The images emerged as museums, volunteers, and ordinary Ukrainians rushed to save the country’s cultural heritage amid escalating Russian military aggression.

In the shadow of this violence, invisibility became both ethics and safety: a strict prohibition on public photography held fast across cities and towns. Yet Subach’s photographs do not merely document—ironically, they shield.

While the world gasped at a theft in the Louvre, a far greater heist has been unfolding for years — the silent erasure of Ukraine’s cultural memory.

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) November 6, 2025

It’s about identity under attack, not just stolen objects.

🧵 1/15 pic.twitter.com/ibUPtDqs9e

The direct flash she employs evokes reportage, crime scene photography, even sensationalism; it also asserts a moral attention, a care for the vulnerability of what is seen, and what must remain unseen.

Subach’s work does not stand alone. The latest edition of Paris Photo’s Carte Blanche highlights emergent voices across Europe, and in 2025, Ukraine is represented by Viktoriia Tymonova—a Master’s student at the Academy of Arts, Architecture & Design in Prague (UMPRUM).

Tymonova navigates the liminal terrain between official histories and the hidden, the fabricated, and the conspiratorial. Her project, We Want to Know the Truth, blends fiction, reenactments, and memory to question the limits of knowledge and the construction of reality. “Why would you pay attention to the mysterious death of an ordinary person?” Tymonova asks.

Her words reverberate like an incantation, charting a path through the improbable and the suppressed. Her work has appeared at Le Centquatre Paris, PLATO in Czechia, and multiple Ukrainian venues, and now it circulates once again in the global arena.

Ukrainian photobooks and emerging voices at the fair

The Paris Photo photobook awards, too, bear witness to Ukrainian visibility. Since 2012, these awards have celebrated the photobook as a site of narrative innovation; this year, a dedicated section showcases Ukrainian photobooks.

The thirty-five shortlisted titles will be exhibited at the fair and online. The jury—featuring Clinton Cargill of The New York Times, Lesley A. Martin of New York-based Aperture, Brian Wallis of the Center for Photography at Woodstock, among others—awarded special mentions to works foregrounding Ukraine. These include Katya Lesiv’s I Love You (IST Publishing, Kyiv), Émeric Lhuisset’s Ukraine—Hundred Hidden Faces (Paradox, Edam; André Frère Éditions, Marseille), Katerina Motylova’s Loss (self-published, Kyiv), Mark Neville’s Stop Tanks with Books (Nazraeli Press, Paso Robles), and Yelena Yemchuk’s Odesa (GOST Books, London).

The Ukrainian photo scene is not a footnote but a pulse. With the Kharkiv School of Photography, which began in the early 1970s and was a quiet rupture in Soviet visual culture, Ukraine always stood out and innovated.

The polished booths of Alexandra de Viveiros, the curated Carte Blanche exhibitions, the glinting photobooks arrayed like evidence—together map the persistence of Ukrainian visual culture, insistently present in spaces that can, at times, claim neutrality.

And yet the work itself is haunted: Subach’s images of hidden objects and people, Tymonova’s archival conjurings, the photobooks’ testimonies—all bear witness to absence as much as presence. They remind the visitor that visibility, as in photography, in Ukraine is never merely aesthetic; it is necessary.

Amid the global reunion of photographers, Ukraine’s insistence on seeing and being seen—on resilience, on the hidden and the exposed—offers a counterpoint to the spectacle, a reminder that photography is never neutral, never innocent, and always in service to memory.

As Ukrainian photographer Boris Mikhailov spoke of color in his photographs: “Color becomes not just a formal choice, but a way of recording history.”

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-60190095464c40ccbc261d2114a1fe68.png)