- Category

- Life in Ukraine

He Had Two Tickets and a Lie: How One Ukrainian Teen Escaped the Russian Occupation

Ivan spent years under Russian rule in Luhansk. But the night before he turned 18, he made a decision beyond his years and left everything behind to reach free Ukraine. This is his journey.

Ivan Sarancha left his home in the temporarily occupied Luhansk on January 11, 2025. That day, he went to Russia’s Rostov. There, he bought two tickets: one of them—back to Luhansk. Ivan took a photo of it and sent it to his parents. Then, he immediately threw it away. That moment marked the beginning of his roundabout way to Ukraine.

Ivan was brought back as part of Bring Kids Back UA—the initiative of the President of Ukraine, that unites government institutions, NGOs, and international partners to return all Ukrainian children who were deported or forcibly transferred by the Russian Federation.

How to leave the occupation?

"I was looking at my childhood drawings shortly before leaving,” says Ivan. “There was a sketch of a Russian flag, next to a Ukrainian one, which was crossed out. They were telling me what I had to draw and do."

Ivan is sitting in a studio in Kyiv, telling UNITED24 Media what life was like in Russian-occupied Luhansk. He was just seven years old when Russian-backed forces illegally took over his hometown. That was the last time he saw a Ukrainian flag, back when he entered first grade at school. The next time would be 11 years later.

“I remember most vividly the time when I entered second grade,” says Ivan. “We used to sing the anthem of the [so-called—ed.] “LPR ”, and I still remember it. Then we started using Russian textbooks, and teachers began telling us their own versions of the war.”

Back then, Ivan didn’t understand what was going on. “But now I realize it was pure propaganda,” he says.

The atmosphere on the streets also changed, says Ivan: “There was nothing Ukrainian anymore.” While Ivan’s parents were pro-Russian, everything seemed fine for the boy. The only adult around him who supported Ukraine—his grandfather—moved to the Dnipropetrovsk region shortly after the Russian occupation of Luhansk.

“Why would we be enemies?”

Everything changed when he turned 12. It was 2019, and while playing games online, Ivan made some new friends from Dnipro.

"Our whole conversation started with me asking, 'Can we be friends if we're enemies?' And the response I got was: 'Why would we be enemies, if you and I are both from Ukraine?' I replied, 'How can I be from Ukraine if I'm in Luhansk, in the “LPR”?' And they said, 'That doesn’t exist—it’s an occupation.' That’s when my perspective started to change."

After that conversation, Ivan started searching for news beyond Russian propaganda sources. "I was following the major media outlets—BBC, The Washington Post—those are the Western ones I definitely remember."

Making the decision

By the time Ivan turned 15, he was already thinking about moving away from Luhansk.

“At first, it was the desire to meet up with friends,” says Ivan. “I just wanted to see them. But after the full-scale invasion, it turned into a desire simply to live in Ukraine.”

As time passed, Ivan began to realize that he had to start making decisions for himself. “My plan was: find out how to move, earn money, then—distance myself from my parents so they wouldn’t know where I was going, and prepare my documents.” However, as soon as he began looking for ways to move to Ukraine, another problem quickly emerged—there was hardly any reliable, up-to-date information.

“I opened Google and typed ‘how to leave the occupation’ or ‘how to get to Ukraine,’” says Ivan. “There might have been some transport companies or something, but they didn’t really help. I needed to know exactly what to do. Then I opened YouTube and searched for the same thing. I could only find two videos, both already six or seven months old. They didn’t give me a lot of information either, but at least they showed me it was possible.”

The road to freedom

To earn some money for his journey, Ivan worked as a barista with a salary of nearly 1,000 rubles ($12.5) per day. Besides saving up for the trip, he was also paying for his own education.

“In Luhansk, I studied in two different places,” he says. “First, I went to a construction college to study economics. Then, after the first year, I switched to the Academy of Arts to study sculpture. I wasn’t accepted into the second year, so I had to start over from the first, this time as a paying student.” He left halfway through his second year at the Academy to start his life all over again in Kyiv.

“Once, when my father was busy, I took his phone,” says Ivan. “Knowing the password, I unlocked it and started going through his contacts. I didn’t find my grandfather’s contact, but I did find my aunt’s.” Ivan and his friends messaged her, but without a reply. “I thought, well, at least I have the phone number, the surname, and I knew the approximate address—from what I remembered or maybe heard from my parents. I decided to go with that.”

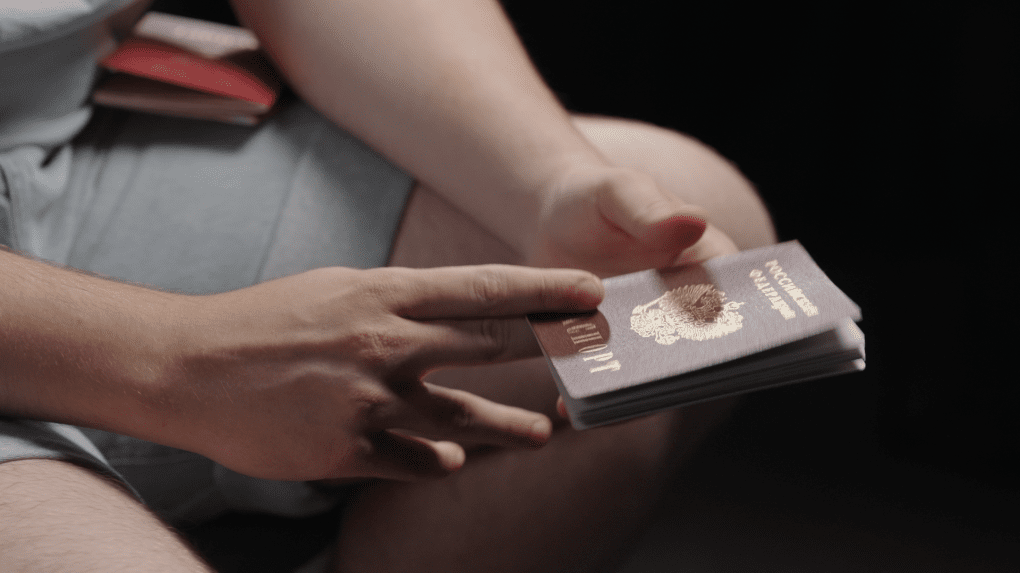

The next step of his plan was to get all the necessary documents. “To leave, you need to have a Ukrainian document. In my case, the only document I had was my birth certificate. Based on that, I submitted an application for a temporary “white passport ” at a Ukrainian consulate.” With the help of his mom, Ivan was also issued an international Russian passport. However, apart from his friends in Dnipro, no one knew about his plan.

A birthday wish

"I told my parents that I wanted to give myself a gift for my 18th birthday—to go to another country, Georgia,” says Ivan. “When my dad found out, he forbade me from going there. We started negotiating. I said I wanted to go to Moscow, which was better for me anyway, but he still didn’t allow it. In the end, we agreed that I would go to Rostov."

On January 11th, one day before his 18th birthday, Ivan started his journey. “When I arrived in Rostov, I immediately bought a ticket further. I also bought a return ticket to Luhansk for January 15. I sent a photo of that ticket to my parents to prove I was really coming back, but then I immediately threw that ticket away.”

Ivan booked a hotel, dropped off his luggage, took a few photos of the room, and then went for a walk around Rostov to take more pictures to send to his parents, who still believed he was on a short trip. Only after reaching Ukraine did he finally tell his family that he wasn’t going back to Luhansk.

Crossing the border

Remembering those days, Ivan says he experienced the most intense fear and stress in his life: “I only took a small bag and a backpack with me, travelling with almost no belongings. In the bag, all I had was some documents, a charger, and a power bank. I had food and two liters of water. In the end, I only drank the water and didn’t eat.”

On January 14, 2025—two days after his 18th birthday—Ivan was safely in Ukraine and on his way to Dnipro, where he would meet his friends in person for the first time.

"I had expected that I would scream with joy, but I was so completely exhausted that I just accepted it as a fact—that I made it,” says Ivan. “I felt like a weight had been lifted off my chest. I just looked around in silence, saw the [Ukrainian—ed.] flag, and realized: I’d done it."

New life in free Ukraine

Ivan spent the first week in Dnipro. It was there, when he told his parents that he wasn’t going to come back. "I was supposed to arrive [in Luhansk—ed.] either at 8 or 8:30 am.” When that time came, Ivan’s mother started texting her son. For some time, Ivan could not reply.

Ivan’s mom: “Where are you?”

Ivan: “I'm in Ukraine.”

Ivan’s mom: “Is this a joke?”

“Then I sent her a photo of the Ukrainian flag," says Ivan.

Ivan doesn’t communicate with his father anymore. However, he keeps in touch with his mother: “Neither my mom, nor my grandmother, nor anyone else accepted this decision. They accepted it as a fact that I’m now here. But to truly accept it in their hearts… no. No one did.”

Starting over in Kyiv

After a week in Dnipro, Ivan moved to Kyiv. For the next few months, he lived in a dormitory for IDPs in the capital city—a place where he made a lot of new friends.

One thing that surprised him a lot was the freedom: “Here you can openly say things against the government, or in support of it. People are so different. Also, the infrastructure, the modern feel of everything. In Luhansk, everything has frozen in time. Nothing changed. But here, life is moving.”

Ivan also decided to return to education. For now, he has chosen to study law. His aim is to help people and protect their rights.

“Hopefully, by the time I finish my studies, there won’t be any more people needing to flee from occupation,” he says. “But if that’s still the case, then I’ll definitely work on that, because I’m already a bit involved now.” Ivan believes that, even now, by describing his experience of fleeing from occupation, he may help some other Ukrainians who want to move.

“When I was searching for information myself, I couldn’t find anything,” he says. “But now I’m a real person, not hiding my name or my face, and I can show people: this is me, I made it out, and it’s possible.”

Ivan’s vision for Luhansk

Though he’s gained freedom and a new life, Ivan’s passion for sculpture hasn’t changed. One day, he hopes to return to this, in particular, to create new monuments in his hometown.

“In Luhansk, the first thing I’d want to do is tear down all Lenin statues and get rid of all the others—that whole Soviet thing,” says Ivan. “I’d remove all of them and replace them with proper, meaningful sculptures. The most ironic thing is that on Lesia Ukrainka Street—which still exists in Luhansk—there’s a monument to a Berkut officer, and nearby is a Russian “basement” [detention site—ed.]. I’d want to tear all that down and put up a real monument to Lesia Ukrainka. That’s the first thing I’d do."

In a memory of his journey, Ivan got a tattoo on his arm—it was designed by one of his friends from Dnipro. "The triangle symbolizes torture, prison bars—basically the confines of life,” he says. “The tornado represents what you need to do to break free and continue growing. Regarding my own story, it reflects the occupation and what must be done to escape it. It’s a symbol of how my life completely changed after that."

FAQ:

When did Russia’s war against Ukraine start?

Russia launched an undeclared war against Ukraine in 2014. Shortly after the illegal attempted annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, Russian special operations units—along with other armed formations—seized Ukrainian local government buildings, police departments, and military facilities in Donetsk and Luhansk regions. They also carried out offensive operations against the Ukrainian army and law enforcement. Numerous Russian troops unexpectedly and treacherously invaded Ukrainian territory and engaged in violent hostilities against the Ukrainian Armed Forces. In 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion, targeting all Ukrainian regions.

What happened to the Luhansk and Donetsk regions?

Parts of two Ukrainian regions—Luhansk and Donetsk—have been occupied since 2014. Back then, illegal armed groups, backed by Russia, started occupying government buildings—and proclaiming so-called “People’s Republics.” Pro-Russian rallies, as well as seizing official buildings, began to spread in other settlements of the regions. On May 11, 2014, the illegal referendum on the status of Donetsk and Luhansk regions was held in the occupied territories. Both of these puppet states received no international recognition.

What evidence points to Russia’s role in the occupation?

There’s overwhelming evidence of Russia’s direct involvement—from the weapons it supplied to illegal armed groups, to the presence of its own troops, and the official attempts to annex occupied Ukrainian territories. For example, the Malaysian MH17 plane was shot down by the Russian BUK missile system that was transferred from Kursk to the Donetsk region. The Kremlin formally declared the annexation of the Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia regions in September 2022, a move unrecognized by the international community except for North Korea and Syria.

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)