- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Ukraine’s Military Penguins Are Real, But They’re Not What You Think

-6a6141d76c3e7b9e99e995edd6ec0612.jpg)

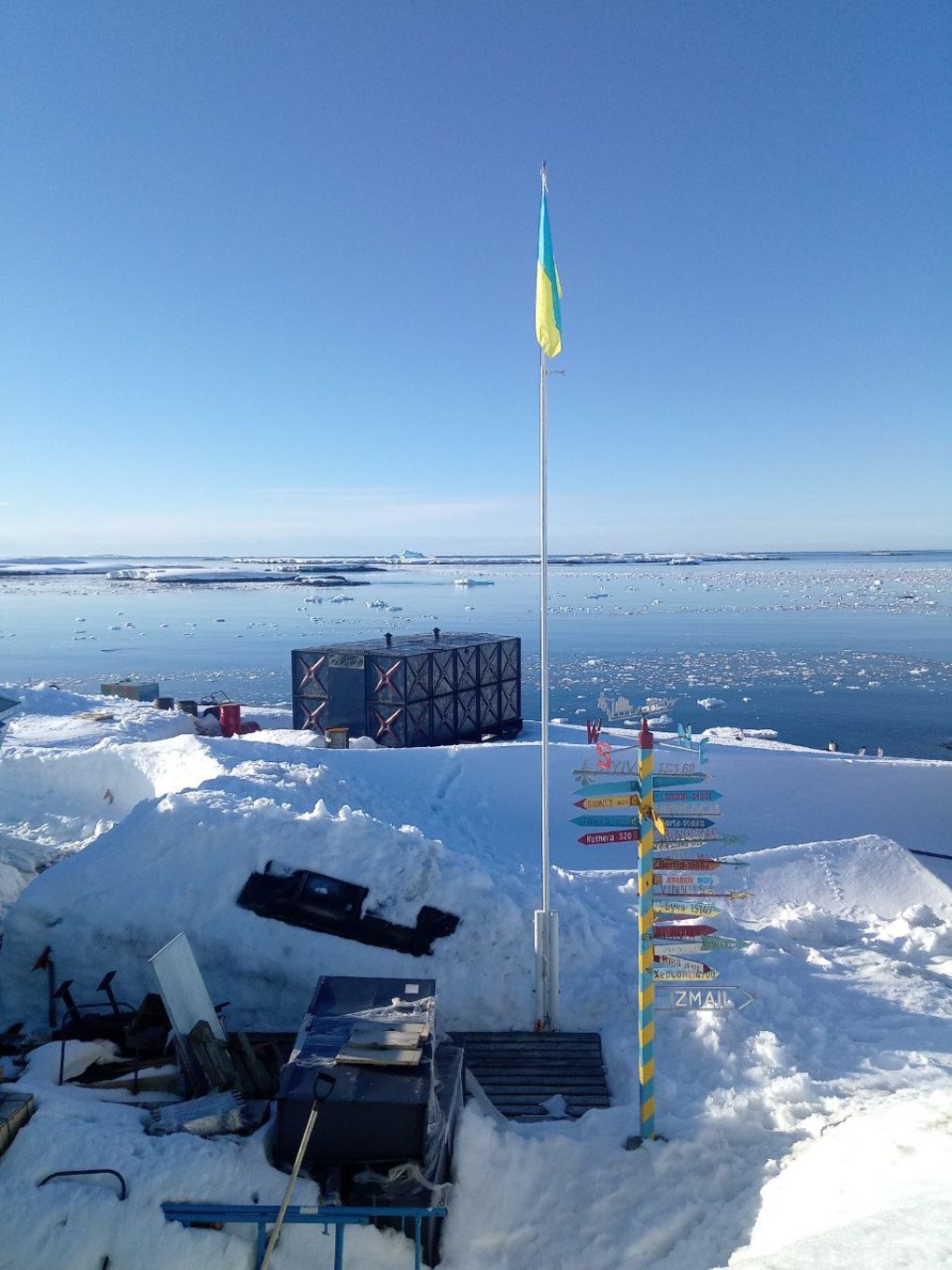

The Vernadsky Research Base is Ukraine’s polar research station in Antarctica. But when Russia launched its full-scale invasion, even this icy frontier wasn’t untouched. Thirty-one polar scientists joined Ukraine’s Armed Forces. They’re now known, unofficially but proudly, as the Military Penguins. This is their story.

This piece can open in two ways. The first captures the romance of the polar mission.

“What strikes you first at the station? Antarctica itself, of course. It’s like flying to space!” says Maksym Bilous, who served as a systems mechanic on two consecutive expeditions. “The natural world is incredible—icebergs, mountains, the ocean, and islands. For the first few days, I couldn’t believe my eyes. That such stunning beauty even exists.”

Romantic enough? Here’s another perspective.

“One thing you notice right away is the penguins,” says Maksym. “It’s far from a cutesy story. Like all living creatures, they poop and pee. Our island isn’t that big, and there are thousands of penguins. Just imagine the smell.”

Today, two species live near the Vernadsky Research Base: the sub-Antarctic penguin, whose population recently hit a record 7,000, and the Adélie penguin, though only a few of them inhabit the island. Other companions to the roughly 15-person station crew include seals, sea lions, leopard seals, whales, and orcas.

All of them are subjects of Ukrainian scientific research. The station’s three main disciplines are biology, geophysics, and meteorology. One crucial task is continuous monitoring at the geomagnetic observatory. These measurements support technologies like smartphones and other global devices, specifically, the accuracy of built-in compasses used in geopositioning. That’s where Vernadsky Base’s research plays a key role.

Ukraine is part of Intermagnet, an esteemed international network of geomagnetic observatories. All magnetic equipment at the station was developed by Ukrainian scientists. They say their instruments don’t just meet Intermagnet’s standards—they exceed them, placing Ukraine’s observatory among the world’s most advanced.

Meteorological research there also feeds into global weather forecasting and long-term climate models. All three disciplines are monotonous but fundamental; breakthroughs come not in years, but decades. The key requirement is continuous data collection. That’s why, when Russia launched its full-scale invasion in 2022, polar scientists faced a tough decision.

At the other pole of the war

“On February 24, 2022, we were in Chile, waiting for the ship to take us to Antarctica,” says Bilous. “It was autumn in the Southern Hemisphere. At midnight local time, we saw the news of our homeland being bombed. No one slept. Everyone was worried for their families, their friends. Many wanted to return home, but that was nearly impossible. COVID restrictions were still in place, and if anyone dropped out, we risked losing the station. Every specialist is essential in an expedition.”

The team ultimately decided all wintering personnel would stay. There are two types of staff at Vernadsky Base: the year-round expedition (winterers) and the seasonal crew of scientists and technicians who work during the summer months. That’s when research activity peaks, as the surrounding waters are ice-free and travel becomes easier.

“We agreed that after the winter, everyone would make their own decision,” Bilous says. “Eventually, two members of the seasonal team hitchhiked on yachts to South America to return to Ukraine and join the defense forces.”

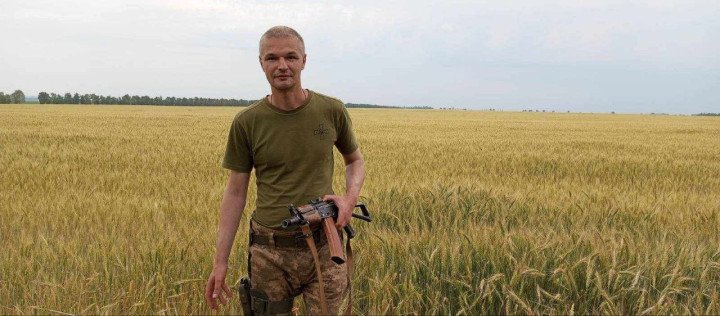

He himself now serves as a sapper in the military, training both new recruits and seasoned soldiers.

His colleague, candidate of sciences Ihor Artemenko, also joined the Armed Forces after returning from the 2020/21 expedition, where he worked as a meteorologist. Science runs in his family—his father, Hennadiy Artemenko, was a geologist, a Doctor of Sciences, and a corresponding member of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. After Russia’s 2022 invasion, his father also volunteered for the military.

“He pulled a trick—didn’t even show his passport at the draft office,” says Ihor. “He was already 72. Someone finally checked in June and said, ‘No way, absolutely not!’ But by then, he’d already been through Bucha, Romanivka, Irpin, and other hotspots. I wanted to prove I was no less capable than my father.”

In theory, candidates and doctors of science are exempt from service unless they volunteer. That’s what Artemenko Jr did. He became head of communications and a platoon commander in the 1st Special Purpose Brigade. He now serves with the 4th Separate Tank Brigade, having fought Russian troops in places like Vovchansk, Lyman, and Kupiansk.

“They didn’t want to take me at first,” Artemenko admits. “Like my father, I had to bend the truth a bit to get in.”

And he wasn’t surprised by the war’s onset.

“For me, it was just a matter of time,” he said. “I know Russian history too well not to see it coming. They were massing troops near the border a year before the full invasion. I even remember us talking about it at the Faraday Bar in 2021. We knew if war broke out while we were wintering, we wouldn’t be able to get out and help.”

The Faraday Bar? That’s right.

The station was originally established by the British in 1947 as Faraday Station. Ukraine purchased it in 1996 for a symbolic £1. That very coin is now embedded in the bar counter of the southernmost bar in the world, named Faraday. It has three tables and seven seats. In the book Straight Up: The Insiders’ Guide to the World’s Most Interesting Bars, Faraday is named the best bar in Antarctica. Though also the only one.

In recent years, the main topic of conversation there has been the war. But some traditions from peacetime endure. Every Saturday, off-duty personnel gather for a formal dinner. Men wear suits and ties; women wear blouses or dresses.

“It’s a harsh environment,” says Bilous. “But we didn’t want to become savages. These traditions help us keep it together.”

Now, their polar experience helps them keep it together on the battlefield.

The Military Penguins

“If you’re a scientist, you have to be flexible and quick to adapt,” says Artemenko. “On an expedition, you learn that even more. The polar hardship gives you extra strength. Sometimes in the army, someone would shout, ‘I’m a career soldier!’ Well, I can shout just as loud: ‘I’m from the Academy of Sciences. I’m a polar scientist.’ So what?”

Only the most qualified make it to Vernadsky Research Base. The selection process involves multiple stages, including interviews, psychological assessments, medical exams, and team coordination, often resembling special forces tests.

Today, the polar scientists form a real community. The 31 Military Penguins stay in touch. They represent every Antarctic role: scientists, mechanics, cooks, medics, diesel engineers, sysadmins. Now, they’re communications officers, sappers, infantry, drone operators, and scouts. They even have their own unit patch featuring a penguin with a flag. “It’s like a big family,” says Maksym.

The group also holds regular charity auctions of memorabilia—photos, handmade items from the station, and patches. The most sought-after item is a virtual tour of the base. All proceeds go toward equipping or supporting polar veterans in the Armed Forces.

Some have been wounded. Yurii Lyshenko, who took part in several Vernadsky expeditions, led an assault team with the 54th Mechanized Brigade. In fall 2023, a Russian mine hit his trench. He lost part of his leg. While recovering in the Kyiv region, he came under fire again—and miraculously survived. In February 2025, he returned to the polar station.

“Now I’m an Antarctic pirate—with one leg and a penguin on my shoulder,” he jokes.

Ihor Artemenko is currently in a hospital, recovering from combat-related health issues.

“I work in communications, which is vital,” he says. “I don’t have the luxury of choosing whether to go to the front, no matter how I feel. The tank crews trust me. They know I’ll come, day or night, hot or cold. Under fire, I think: will I make it through? I give myself an injection and go. But now, the health problems have piled up. At some point, my legs just stopped working,”

Constant danger takes its toll.

“In Antarctica or when mountaineering, I faced risks too,: he says. “But war is different. When you live under threat long enough, you stop sensing danger. That’s dangerous in itself. You forget the body armor, let your guard down. But we have a reason to live. We all do.”

After the war, he plans to return to science. “Being a scientist—it’s for life.”

A few hours after the interview, Ihor sends a message:

“I’ve been thinking about your questions. You know what’s truly terrifying in war? When you’re unsure your loved ones back home are safe—your daughter, your wife, your mother. That fear is real. Getting shot at, drones, bombs—that’s the daily reality. An airstrike hit a tank I was fixing a radio in. One hit a building I was in—here it is burning in the video,” he shows. “That was five days before I was supposed to go home on leave. But what if I had no one left to go home to? That’s the scariest part.”

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)