- Category

- Life in Ukraine

Ukrainian Teen Marta’s Daring Escape From Russian Occupation to Freedom

Having secretly enrolled in a Ukrainian online school and waiting for her 18th birthday, Marta was finally able to leave Russian-occupied Donetsk in spring 2025. Without saying a word to her parents, she packed her belongings and headed to Kyiv. Marta told her story to UNITED24 Media.

Marta’s journey is told with the help of Bring Kids Back UA—the initiative of the President of Ukraine, that unites government institutions, NGOs, and international partners to return all Ukrainian children who were deported or forcibly transferred by the Russian Federation.

Keeping a secret

Marta came to the studio interview along with her friend Serhii, who she met a few years ago in Donetsk. They shared the same idea—that they are both Ukrainian and that Donetsk is a Ukrainian city.

“I met most people who felt like this online, or they were friends of friends,” Marta told us when asked about her like-minded friends. “With most of them, we just spoke Ukrainian in everyday life—we weren’t afraid to talk about politics. Even though there were a lot of Russian soldiers on the streets of Donetsk.” Many of her friends are still in Russian-occupied territories.

This was Serhii who played an important role in Marta’s life—he helped her discover a way to flee the occupation.

“I had been waiting for this for a very long time,” she said. “Since I was 15, I was literally counting down the days until I turned 18 so I could leave.” Born and raised in Donetsk, Marta was in 2nd grade when the Russians occupied her city. Shortly after, she moved in with her relatives in Mariupol for several months.

“The clearest realization of what had happened came when I returned to Donetsk—by my own choice. I saw all those tricolors, their [Russian—ed.] posters, and the changes in the education system.” Right after the occupation, her school teachers were continuing to use Ukrainian textbooks “which hadn’t been burned yet”; however, they asked the pupils to keep it a secret. “Don’t tell anyone, because we could be arrested for it,” Marta said, remembering her teachers’ words.

But the next school year was completely different. “They had already started fully adapting to the Russian curriculum,” Marta said. “The entire system is built on Russian propaganda— they organized events where they would bring in soldiers. Or they had their clubs, like ‘The Movement of the First ,’ or the subject ‘Conversations About Important Things,’ which is full-on propaganda glorifying Russia.”

“Even those [pupils—ed.] who are more pro-Russian just find it funny—what they’re being told and what they’re being taught,” Marta says.

At home, the situation was almost the same, as Marta’s parents had (and still have) a pro-Russian stance. “At first, I didn’t talk about my views at all—I understood it was better for me to stay silent. But then, at some point, when they either found some of my Ukrainian notes or something like that, I had to admit it,” she recalled.

Back then, Marta told her family about her plans to leave: “I don’t care what you think about it. I’m not trying to convince you—I understand there’s no point.” In the end, though, Marta had no choice but to smooth things over, since they continued living in the same apartment. “And so I kept it a secret again, all those years.”

Quiet preparation

“I never saw myself as Russian, and I never considered Donetsk to be Russian,” Marta stressed. From childhood, she knew she was Ukrainian. “I honestly don’t know why everyone else there doesn’t feel the same way. I think it’s just crazy to have a different opinion or take a different stance.”

At the same time, to share this opinion can be dangerous in Donetsk nowadays. “How would you describe the occupation?” I asked Marta. She thought for a moment before answering: “To me, it just feels like some kind of senseless survival game. The only goal is to preserve your own consciousness.” Marta continued: “Being yourself every day—for them, that's a criminal offense that can get you 15 years in prison.”

In 2022, Marta made her final decision to leave Donetsk and immediately started looking for ways to make it happen. “After the full-scale invasion, it all just piled on even more—all that talk about Russia. Because before that, they first acted like the so-called “DPR ” was in charge, and only later came the so-called “joining” Russia.” Being underage, however, made the process of leaving complicated.

”I looked for organizations or companies that could take a minor out without parental consent,” she says. “I also spoke with relatives from Mariupol who by then had moved to Kyiv.” Together they realized it was unlikely she’d be allowed to cross the border without the necessary documents. Hoping Marta’s parents would give permission was pointless. “My relatives advised me to just wait and focus on preparing.”

In 2024, Marta enrolled in a Ukrainian online school. After attending university classes in temporarily occupied Donetsk, she would come home and continue her secret studies to obtain Ukrainian certificates.

“I had very little free time, but whenever I had the energy, I would do all the assignments and online tests.” The only thing she couldn’t do was join the online lessons. “I wouldn’t have been able to do it without being noticed,” Marta explained.

At the beginning of 2025—a few months before her 18th birthday—she began communicating with volunteers from the organization her friend, who had moved from Donetsk a year earlier, had told her about.

“We planned everything together [with a volunteer—ed.]: the dates, waiting until enough people joined so I wouldn't travel alone.”

In the first week of April, Marta packed her belongings. Her parents, who thought that she was somewhere in the city, knew nothing of her plans. The next time she would talk to them was from Kyiv—their last phone call to this day.

Welcome home

It took several days to get to the border.

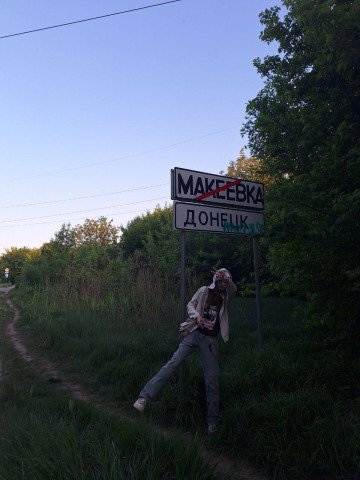

“When I saw the Ukrainian flag and the sign saying it was a Ukrainian checkpoint, I realized I was on the right path. The road was quite difficult— inconvenient to cross with all my belongings—but I was completely in the mindset that I would make it no matter what, that most of the difficulties were already behind me.”

A few days later, Marta was safely with her relatives in Kyiv.

“I didn’t have a clear idea of what might happen in Kyiv, but my aunt insisted that I stay with her for a while. First and foremost, I needed to take care of my documents, and only then could I think about education,” Marta explained.

As of now, she has already enrolled at university in Kyiv, choosing to study the Japanese language. Now in the Ukrainian capital, Marta is making new friends, but still communicates with those who remain in Donetsk. She strongly believes that one day she will be back in her hometown.

“I would like to return to Donetsk—when it’s de-occupied. I would like to meet friends who are still there—if they’re still around. And just try, with all my strength, to rebuild everything that was destroyed.”

-73e9c0fd8873a094288a7552f3ac2ab4.jpg)

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)