- Category

- Perspectives

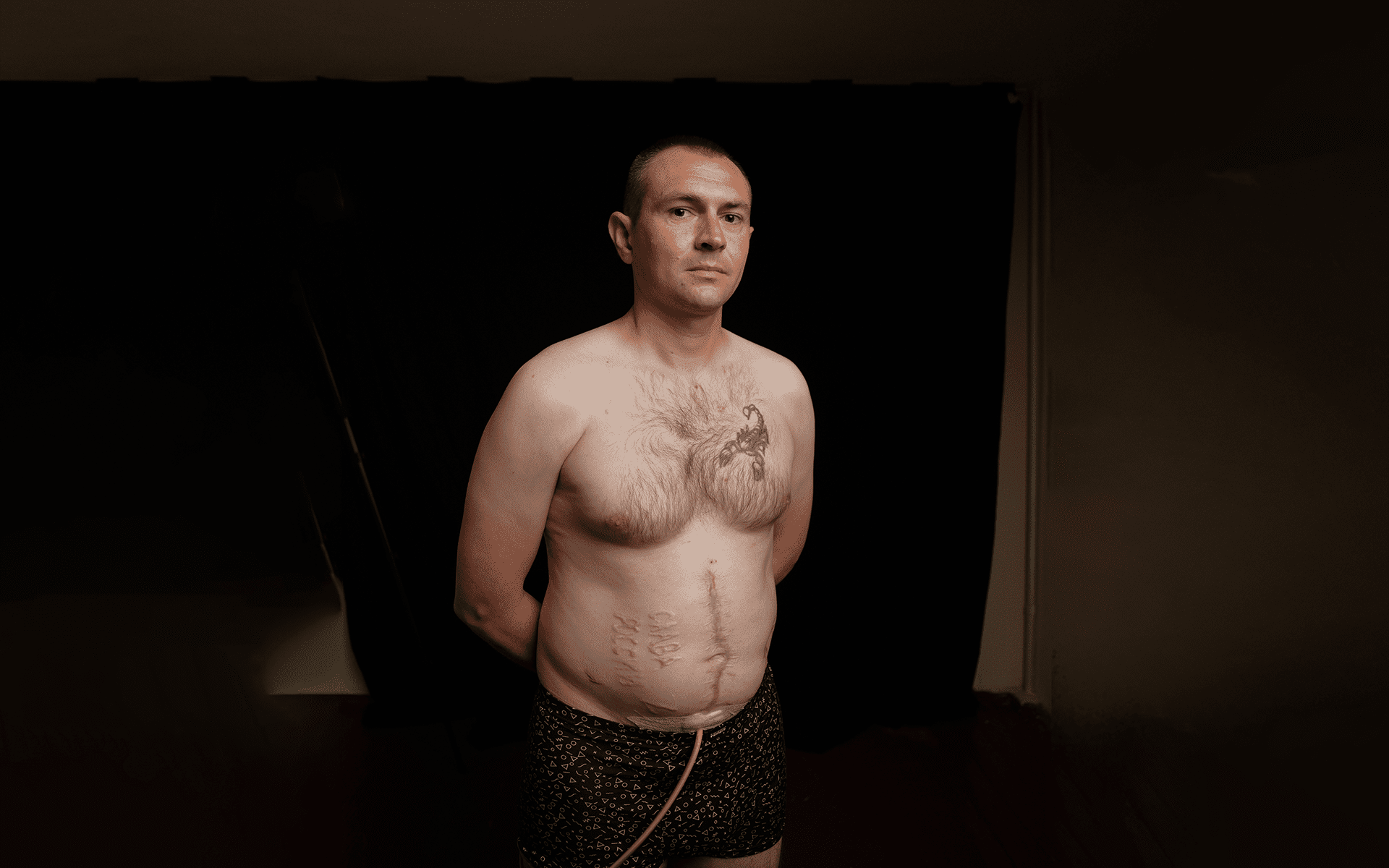

“They Burned ‘Glory to Russia’ Into My Stomach”: Ukrainian Soldier’s First Interview After Torture in Russian Captivity

Andrii, a paratrooper from Ukraine’s 79th Air Assault Brigade, spent over a year in Russian captivity. Tortured, starved, and left with scars both visible and invisible, he returned home thanks to a prisoner exchange in May 2025. Here’s his story.

In February 2024, Andrii fought in the Donetsk region with his unit. They were repelling Russian assaults for days when a grenade blast badly wounded Andrii.

“My first thought was that my legs had been blown off,” says Andrii. “I reached down—they were still there. But I couldn’t feel them.”

Losing consciousness from blood loss, he was dragged out of the dugout by Russian troops. Unable to walk, he was loaded onto a stretcher and taken behind enemy lines.

I thought I was done for. While they were carrying me, I kept asking them, ‘Finish me off, just end it.’ But they didn’t.

Andrii

Basement torture and the first “welcome”

His first stop was a basement.

Blindfolded and with his hands tied, Andrii was “greeted” with three hits to the head with a five-liter plastic bottle filled with water. He blacked out, only to be revived for interrogation.

“I already knew… they were going to break me. Hard.”

In practice, interrogation means torture. While trying to obtain the information about weapons, the number of soldiers, and the positioning of the Ukrainian forces, the Russians used electric shocks on his open wounds until Andrii lost his consciousness again.

“Once they found out what kind of unit I was from, it set them off. They were furious.”

The torture lasted for hours, from midnight until dawn.

“A surgeon did this to me”

In the morning, still blindfolded and bound, Andrii was put onto an operating table. After the surgery and two days in intensive care, Andrii ended up in a hospital bed under guard.

“They came to change my bandages, and a nurse came in,” he says. “I just lay there, staring at the ceiling.”

The nurse said, ‘Don’t worry. You can cover it up when you get home with a tattoo or something.’ I had no idea what she was talking about. Absolutely none.

Andrii

A few days later, he lifted his head for the first time to check his wounds. On his stomach, burned into his flesh, were the words: “Glory to Russia.”

It was done by the surgeon who had operated on Andrii. A Russian medic used a medical cautery tool—designed to stop bleeding during surgeries—to mutilate him.

When Andrii protested, the guards poked him in his wounds with their fingers.

For two months, Andrii couldn’t leave his bed – he was too weak. Once the guards learned Andrii had started walking again, they called on their superiors to inform them.

“A group of guys came to see me… real lowlifes,” he says. “Supposedly for an interrogation, but it wasn’t that. They just came to entertain themselves, to torture me for fun. One guy was sitting at a table, typing on a laptop, while the other one was torturing me. He kept hitting me on the ears, punching the back of my head, and using a stun gun on me. They asked me where my wound was—I pointed to my leg. So they ripped off the bandage and started electrocuting me right there, directly into the wound.”

After minimal recovery, Andrii was transferred to a prison colony in the temporarily occupied city of Chystiakove in the Donetsk region.

From the hospital to a prison colony

For most Ukrainian POWs, the absolute nightmare begins with the so-called “reception”—a brutal ritual of beatings, stun gun attacks, and psychological humiliation right after POWs enter the colony premises.

Because Andrii was still classified as a “300”—meaning seriously wounded—he avoided the worst of it. But others weren’t as lucky.

“I got hit once across the back, and that was it for me. But the guy behind me—Mishanya—he had serious leg injuries, full of shrapnel wounds, barely able to walk. Because he couldn’t run, he was just slowly walking. They beat him down with their batons, pinned him to the ground right there on the asphalt.

The conditions inside the cell, which prisoners called “the hole,” were inhumane. Overcrowded, cold, no space to lie down, and 16 hours a day spent standing on swollen legs.

“It was cold. We had just taken a shower, and they gave us only underwear and pants—that’s it. Barefoot on the concrete floor, just in underwear and pants, no shirt, no socks, nothing. They gave us our clothes back on the fourth or fifth day. On the fourth day, we got our clothes, and on the fifth, they gave us our shoes.”

There was another constant: mandatory recitation of the Russian national anthem.

“Those who didn’t know it—they’d get beaten. Severely. Beaten until they couldn’t get up.”

The exchange

Andrii spent four months in the colony, fighting infection, malnutrition, and despair.

On May 22, 2025, after more than 14 months in captivity, he heard his name read out on the exchange list.

Crammed into a transport van, they were finally driven to the exchange point and onto a plane. They were held for hours at Rostov airport grounds in the heat, with no food, water, or toilet access.

“When we saw our buses arriving… that’s when my heart started pounding for real,” Andrii recalls.

When he finally crossed into Ukrainian territory, he kept only one thing in his mind:

That promise to his daughter.

When I saw my daughter again, she didn’t recognize me at first. But I knew her right away. I kept my word. I came back.

Andrii

Torture as policy: Russia’s systemic crime

Andrii’s story is not isolated.

Since the start of Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine, over 96,000 criminal cases of war crimes have been opened under Article 438 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine, Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) reported.

Hundreds of Ukrainian POWs across multiple Russian colonies report the same patterns:

Electric shocks

Beatings with rubber batons

Broken ribs, limbs, and noses

Psychological humiliation

Systematic physical torture

These are not random acts of cruelty—they are systemic, deliberate, and likely sanctioned at the highest levels of Russian command.

Andrii continues to recover.

Despite multiple surgeries and lingering injuries, he hopes to return to military service, depending on what the doctors say after his next operation.

“If I can carry body armor again, if I can lift heavy stuff… I’ll go back.”

-588ae190d45987800620301cc34e2cf8.png)

-886b3bf9b784dd9e80ce2881d3289ad8.png)

-c42261175cd1ec4a358bec039722d44f.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)