- Category

- Photoreports

You Hand Ukrainian Soldiers Disposable Cameras. They Show You the War You Rarely See

“This film roll is both a record and a reminder,” says one Ukrainian soldier. This is a story of how a camera carried in a pocket becomes a diary of dust, silence, work, people, and the moments that survive between missions.

In early 2025, as Russia’s advances intensified and the places that had been relatively safe to reach grew increasingly dangerous, the problem was that there was no longer enough time to reach the front lines. However, the need to reveal the truth about the war only grew. So a new idea emerged—let the soldiers document themselves.

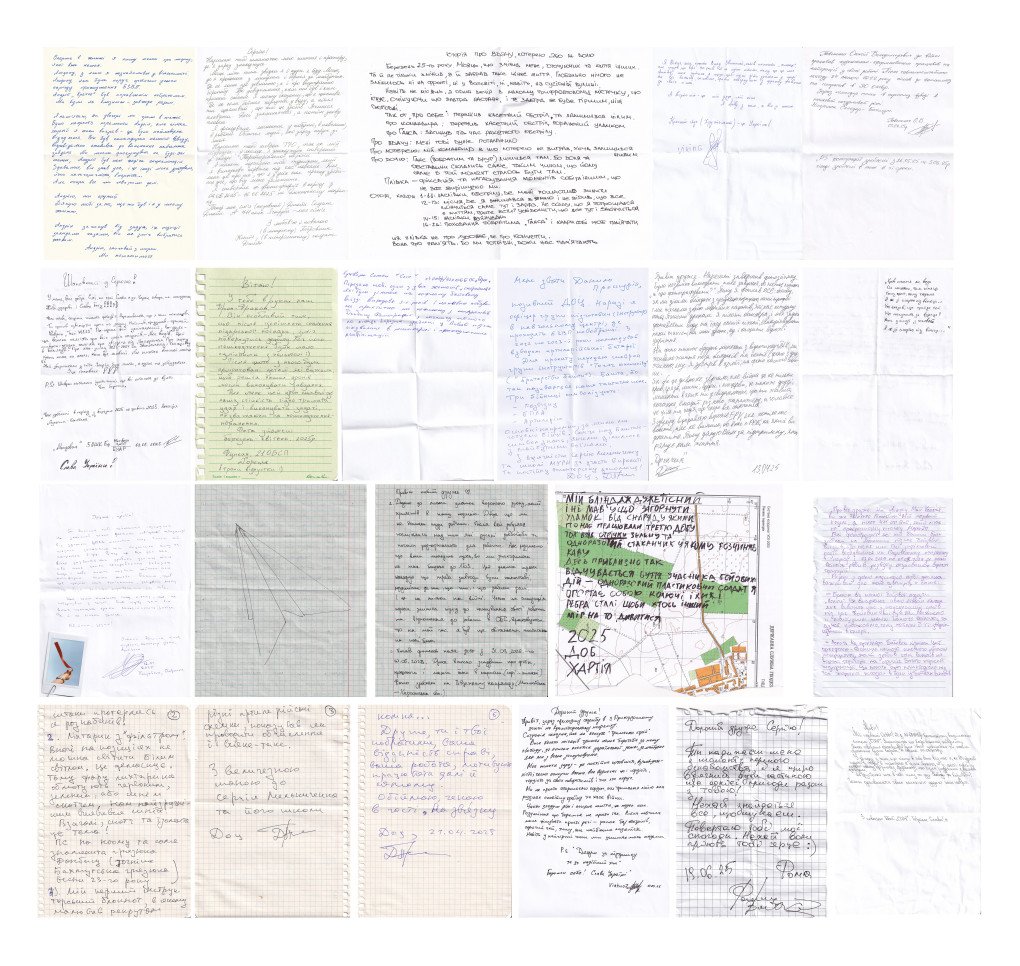

Fotovramci photography company supported me—this is how 25 disposable cameras were sent to servicemen and women across Ukraine’s different fronts. Each soldier was asked to capture whatever they wanted: their routines, their work, their silences, their landscapes. And when the cameras came back, they returned with something more: a personal artifact, a handwritten letter, and a fragment of memory.

This became a frontline diary told from the inside: cockpit reflections, dusty roads, dugout kitchens, fields at sunset, camouflage suits, and the marks of a war carried on walls and vehicles. Together, these images form a human archive of how Ukrainian soldiers live through the war—one disposable frame at a time.

“I’m a bomber drone pilot,” says Andrii, callsign “Dronchik” who joined Ukraine’s military in August 2022 immediately after his birthday.

Dronchik says his responsibilities are straightforward:

Deliver water and food to the infantry.

Evacuate the “Mavics” and other drones.

Destroy Russian positions.

“I worked as a cook and lived a carefree life,” he writes. “Couldn’t even imagine that life was just beginning. In the army I met comrades who will always help. I met my love. Will build my family. And we also got a dog. Here I understood the value of life, and how awesome it is.”

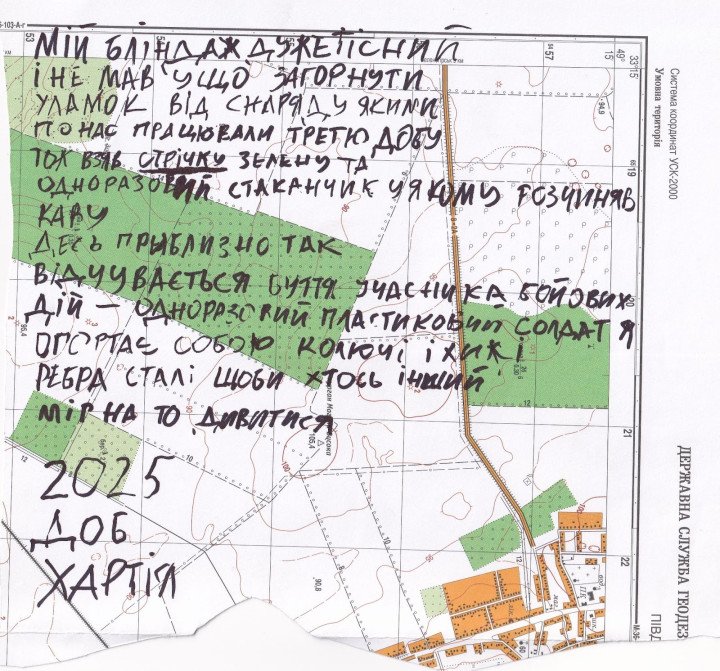

“My dugout is very cramped,” says “Dob,” a soldier in Khartiia Brigade. “I had nothing to cover the shrapnel with—the one from the shells that had been hitting us for three days straight.”

Dob talked about how he decided to join the army ranks: “I didn’t feel I was doing enough in the rear. In civilian life I was first a photographer, then a volunteer, then a disabled person. It can be bad in the army, but somewhere outside the army is even worse.”

“I had someone and something to defend,” said Danylo Proskurin, callsign DOC, a senior lieutenant and instructor at Ukraine’s Instructor Training Centre, explaining his decision to enlist.

He first joined the Territorial Defense Forces’ Legion D and formally entered the Armed Forces of Ukraine in May 2022. He later served as a mortar commander and then as an artillery platoon commander in the 23rd Separate Special Purpose Battalion.

In April 2023, Proskurin injured his knee while on the frontlines. After surgery, he was reassigned as an instructor. Before the war, he taught mathematics at Shevchenko University, where he holds a doctorate in physical and mathematical sciences and served as a professor.

“Now I feel absolutely in my place,” he writes. “Teaching is my thing, and I am not ready to return to civilian life yet. For me, the army is, above all, a sense of brotherhood. It is hard to describe—you can only understand it from the inside.”

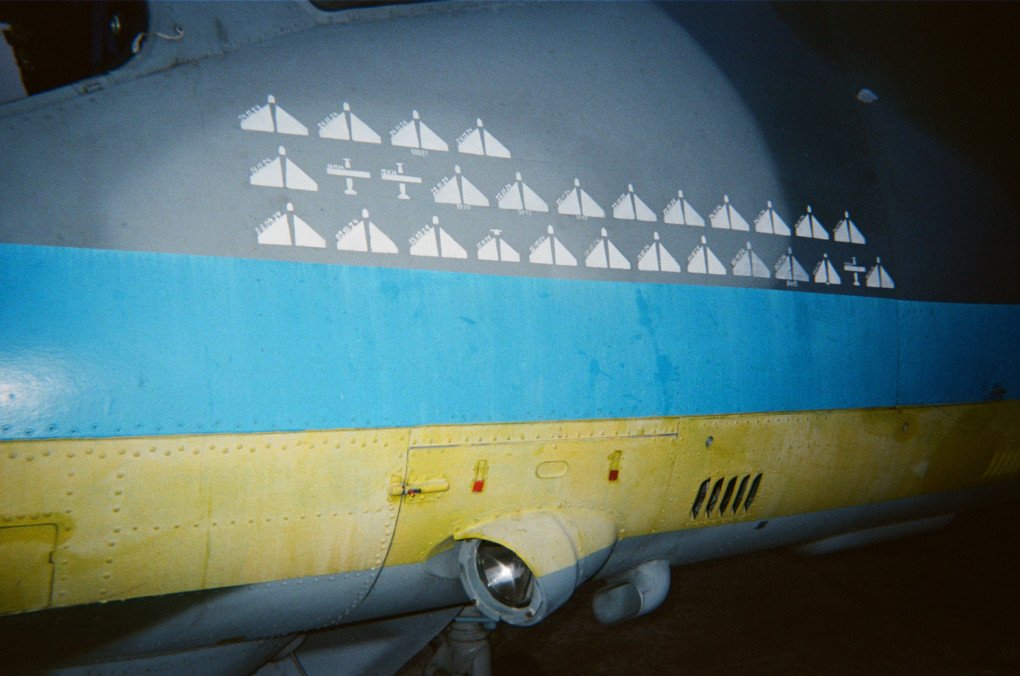

Vlad, who goes by the call sign “Viking,” did not start his path with mobilization. “I am a career officer,” he says. “My military path began back at the military lyceum. That’s where you realize whether you will become a soldier at all.”

He barely remembers himself as a civilian. “I have been wearing the uniform for 15 years already,” he writes. “In fact, I dreamed of becoming a reconnaissance man, but accidentally became a pilot.”

“As they say, where aviation begins—the army ends,” Viking added, suggesting that military discipline in aviation units is less rigid than in other branches.

Max, callsign “Kodak,” joined the military in 2023. After a pause, he returned in 2025.

“The decision was made after my trips as a photographer to the Donetsk region,” says Kodak. “Seeing the reality and how things are, I decided to join the Armed Forces.”

Before the invasion reshaped his life, Max worked in art and photography. He ran a small shop selling film cameras, took on creative and commercial projects, went hiking, traveled. “I was living my best life,” he says.

“In the army I remained a photographer—with one key difference: now I photograph ‘those fuckers’ from the air,” writes Kodak. “I am exactly where I should be, doing everything I can to make life easier for our infantry who are defending the country on the front line.”

Kseniia, callsign “Jane,” joined the military on March 14, 2025. She describes the decision not as a rupture, but as a continuation—a path that began with Russia’s full-scale invasion.

At first, there were other obligations. Her mother was facing severe complications from cancer, and Kseniia stayed until both parents were back on their feet. The time mattered. So did the debt it created.

“For that chance,” she says, “ I am deeply grateful to those who defend us, those who died, those who became veterans, and those who are now in captivity.”

Struggling to list her reasons for joining, she settles on the simplest explanation: there were many. She wanted to defend her country, her family, her people. “For Dasha and Dan from Sema, an organization working with TB and HIV patients; for those who endured occupation and captivity; for Lyosha, a UAV pilot with Azov who was killed in February; and for my fallen friends who once defended me.”

Before the war, Kseniia worked as a photographer and artist. “I filmed, edited video, worked in the film industry and in charitable foundations,” she says. “Now I am a UAV operator. It was important for me to do combat work.”

“In the army, I feel calmer,” she writes. “For the first time during the full-scale invasion, I have found a certain peace of mind, despite everything. Part of me still feels that I am not doing enough, but now this feeling no longer haunts me the way it used to.”

Photography has been part of Viktor Holikov’s life for nearly fifteen years. Now a serviceman, he continues to photograph for himself, documenting the ordinary moments near the front line, trying to preserve the fragile “here and now.”

Holikov listed a series of facts about his life in a letter, each framed as a brief reckoning: He survived a cluster munition strike without injury. “I was very lucky that day,” Holikov wrote. His commander was wounded by shrapnel. Hans, a fellow soldier and close friend, was killed in a missile attack.

His commander, Holikov notes, “did not win the lottery—but he survived.” Hans, he said, remained where he was: “Fate and circumstance lined up in such a way that he happened to be there at that very moment.”

“This film roll is both a record and a reminder—for myself and for others—that not everything is in our hands,” Holikov concludes.

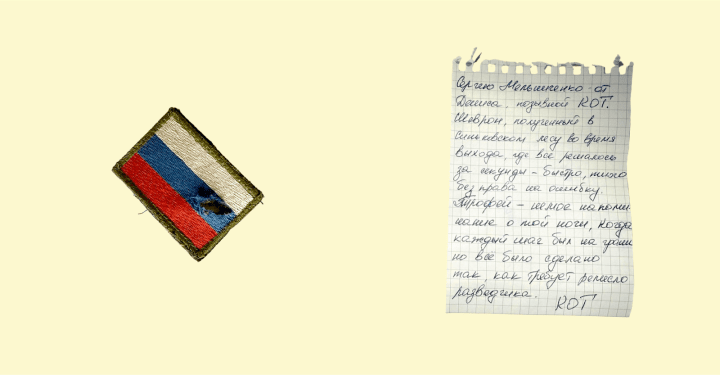

“I joined the military on October 18, 2023,” said Denys, who goes by the callsign “Cat.” Before the war, he ran his own business.

He fought near Kupiansk and later deployed to the Donbas, including the areas around Vesele, Siversk, and Zvanivka. “The situation is very difficult,” he said. “Unfortunately, the Russians are advancing.”

The chevron was taken during an exfiltration in the Synkivskyi Forest, an operation in which decisions were made in seconds and mistakes were not an option. It became a trophy and a silent reminder of that night, when every step carried risk but the work was carried out as the craft of a scout requires.

Denys, callsign “Cat”

Roman, callsign “Fjord,” joined the military in 2024. “It is my civic duty and a desire to be part of the events in the country. Before the full-scale war, Roman worked as a photographer. In the military, Fjord remains one as well, though the work bears little resemblance to what he did in civilian life.

“The photography is completely different,” he says. Much of military life, he notes, has little to do with photographing heroism. “I chose myself the place I wanted to join. The people around are wonderful, the conditions too.” Most importantly, he feels connected to what is happening in the country.

For him, and for many heroes of these stories here, that sense of connection matters.

The photographs featured here are part of Frontline Rolls: Photographs, Letters and Artifacts from Ukrainian Soldiers, a book where scattered film rolls, handwritten letters, and personal objects from the frontline are brought together into a single coherent narrative.

-f223fd1ef983f71b86a8d8f52216a8b2.jpg)

-5c1ba3fedbff10460136c89c0d3db7e9.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)