- Category

- War in Ukraine

Beneath Six Silent Reactors: Russia’s Military Takeover of Europe’s Largest Nuclear Plant

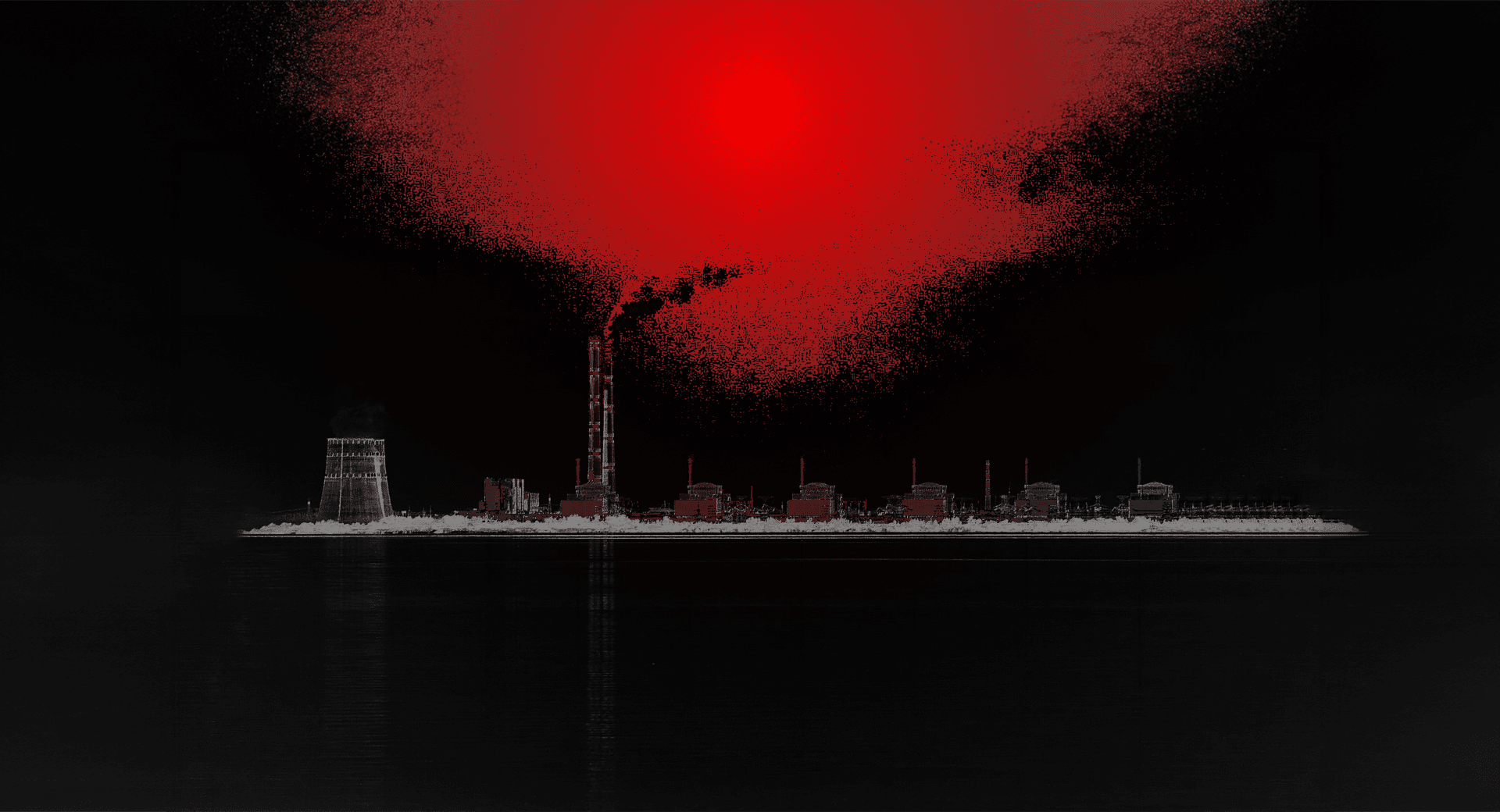

Four years into Russia’s full-scale invasion, Europe’s largest nuclear power plant no longer produces electricity. Instead, it shields a Russian military base.

“In the morning, at around 8 or 10 o’clock, there was targeted shelling,” say Andrii and Halyna, Marhanets’ residents. “Eleven shells were fired at the street. Our neighbor was killed. When the shell hit, she went out into the street to see how her windows had been blown out. Then a third shell hit, and shrapnel killed her right under her house.”

Marhanets lies eight kilometers from the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP)—the largest in Europe. The site is under Russian occupation and has been turned into a military base.

“They’re using the nuclear power stations as cover. We don’t have permission to shoot in that direction,” says Ostap, a local resident.

The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant is no longer generating electricity. Its six reactors are shut down. The territory now hosts armored vehicles, heavy machinery, artillery, multiple rocket launch systems, and a FPV pilot school (training ground).

For the first time in history, a nuclear power plant was seized by military force while its reactors were operating at maximum capacity. At the time, 12,000 employees were working there.

The seizure

The Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant is the most powerful in Europe, explains Yurii Malakhov, Chief Executive Engineer of the KyivEnerhoproect R&D center. Its 6,000-megawatt capacity is roughly comparable to the total nuclear generating capacity of countries like Slovakia or Hungary.

“There was a small battle, and our soldiers suffered losses, as did the enemy,” recalls Enerhodar deputy mayor Ivan Samoidiuk. “But when they started firing at the buildings, both the station management and the battalion had no choice but to raise the white flag. Because when shells are flying into the nuclear station, it's too serious.”

International humanitarian law strictly prohibits military operations near nuclear facilities, says Yevhenii Nahornii, Chief of the CBRN Defense Forces of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. Accidents at such sites would not remain local. They would be global.

“As they fired at the station from their tanks, they said that nothing would happen to it,” recalls Oksana, a former ZNPP employee.

Malakhov calls it unprecedented—the first military seizure of a nuclear power plant in world history.

From power plant to military base

What followed was not chaos but structure.

Nahornii says the operation appeared planned. Under Russian occupation, ZNPP ceased generating electricity and became a military base. Armored vehicles, heavy machinery, artillery, and multiple rocket launch systems were stationed on its grounds.

The transformation extended beyond military hardware.

Together with the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB), Rosatom initiated what local officials describe as “filtration.” Collaboration with the new administration became mandatory.

“If, within the first hour, the head of Rosatom called the station director and said, ‘Welcome home,’ then it's clear that this was entirely expected; they did it,” says Samoidiuk. Russian specialists arrived almost immediately to supervise the Ukrainian staff.

Before the Russian occupation, Enerhodar’s population stood at around 50,000. Today, it is roughly one-fifth of that, according to Denys Sultanhaliiev, Senior Researcher at Truth Hounds, Ukrainian human rights organization.

Truth Hounds has documented 226 cases of illegal detention involving Enerhodar residents and ZNPP workers. At least 78 were plant employees. Thirteen remain in Russian captivity or have already been sentenced by Russian courts.

The basements

“It was done quietly,” Samoidiuk says. Loyal managers were instructed to persuade staff to sign contracts with Russian authorities. Those who refused were detained and taken to basements by the FSB.

“When I heard the terrible things happening in the hallway, I ran to the peephole and saw some guys there,” recalls Oksana. “I turned to my husband and said, ‘Well, they've probably come for you.’”

They tied her husband’s hands. They beat him. Her mother pleaded: “Please don't do this, there are children in the house.”

When Oksana was later told to bring her husband new clothes, she complied. The items returned to her were burned by electric current and covered in blood.

“I just sat there,” she said. “I couldn’t eat or drink. I just didn't want to live. The children sat next to me and cried.”

Tetiana, another former employee, says masked men took her husband from his workplace.

Truth Hounds has documented beatings, electric shocks, strangulation, and severe detention conditions. Some detainees were reportedly forced to assault others. Medical workers were told to revive tortured prisoners so interrogations could continue.

Enerhodar, Sultanhaliiev says, now resembles a city prison—especially for nuclear specialists whose technical expertise makes them too valuable to release.

Rosatom’s role

The occupation is not only military. It is corporate.

Malakhov describes a system in which Rosatom specialists—not ordinary soldiers—determined which Ukrainian engineers were indispensable and which could be pressured. Only someone who deeply understands the station’s management structure, he argues, could have conducted such targeted filtering.

Sultanhaliiev notes that both Kremlin-appointed “mayors” of Enerhodar of Enerhodar built their careers within Rosatom structures. Enerhodar itself is a Soviet-era satellite city built around a nuclear facility.

Malakhov traces Rosatom’s institutional culture back to the Soviet Ministry of Energy and its embedded security officers—a legacy of KGB integration. He argues that Rosatom functions not merely as a corporation but as an extension of state policy.

Across the globe, Rosatom is constructing 24 nuclear projects in multiple countries. Each reactor block may cost between $5 billion and $6 billion. Financing structures often involve Russian state-backed loans, creating long-term political and economic dependency.

“It’s a political act, not a technical one,” Malakhov says.

For four years, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant has remained occupied. No sanctions have been imposed on Rosatom so far.

Nuclear risk

The plant’s six reactors are now shut down. But shut down does not mean safe.

“The destruction of even one reactor—let alone six reactors together with six spent nuclear fuel storage facilities—would constitute a global catastrophe with far-reaching cross-border consequences,” Malakhov says. Weather conditions, particularly wind patterns, would determine how radioactive contamination spreads beyond Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian drone operator Puer describes the territory as vast, filled with hangars and closed structures capable of storing military equipment.

“One can only imagine what types of weapons there are and how many,” he says.

He believes the plant may also serve as a training hub for Russian FPV drone pilots. The infrastructure allows instructors and trainees to operate under the shield of nuclear status.

“For our country,” said Russian leader Vladimir Putin in September 2025, speaking at the World Atomic Forum, “Ensuring nuclear safety and the physical protection of nuclear facilities and installations is an absolute priority.”

Sultanhaliiev says the reality at ZNPP suggests otherwise. There is a fundamental contradiction, he argues, between military use and nuclear safety.

Under FPV

FPV drones fly regularly over Marhanets.

“FPV drones often fly in Marhanets, looking for targets to hit,” says Puer. “But if there are none, they attack whatever they think is worth hitting. These can be buses or trucks.”

Ostap gestures toward a damaged church riddled with holes.

“The church is riddled with holes. Well, the main thing is that the Cossack church is completely destroyed, with about twenty holes. I go in, thinking I'll take a look. And there, not a single icon has been damaged, not one,” he says. “May the truth prevail.”

-7f54d6f9a1e9b10de9b3e7ee663a18d9.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-ca1a63b87c648c14784932e034e42964.jpg)