- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Can Syria’s Conflict—And Now Toppling of Assad—Affect Russia in Ukraine?

In Syria, now fugitive dictator Bashar Al-Assad has been ousted by rebels after decades of atrocities on his people. Russia’s troops located in Syria have scrambled to help Vladimir Putin’s long-time ally in the region without results. What could it mean for Ukraine?

Syrian rebels officially declared the demise of dictator Bashar Al-Assad after taking control of Damascus on Dec. 8 in a historic moment. Al-Assad reportedly fled Syria, and his whereabouts are unknown.

The takeover dealt a significant blow to Moscow’s influence in the region, as the Kremlin-backed Syrian regime collapsed over a week while Russian troops struggled to stop the rebel’s advance.

Syrian rebels moved fast, with the capture of Hama in central Syria on Dec. 5 marking the opposition coalition’s second big victory after Aleppo in an eight-day striking attack aimed at toppling the regime of dictator Bashar Al-Assad.

Assad’s loyalist army faced one humiliating defeat after another, with rebel troops potentially cutting off access to strategic Russian bases for the Kremlin in the Mediterranean Sea.

Putin is now facing a dilemma between keeping Moscow’s foothold in the Middle East and focusing its war effort on Ukraine, according to experts.

Dwindling support for Syria?

Russia has been a staunch supporter of the Assad regime since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011 and formally entered the conflict in 2015. Like Putin, Al-Assad is no stranger to war crimes.

The conflict killed at least 300,000 civilians as of 2022, according to the UN, while the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights documented over 40,000 civilians killed by the Bashar Al-Assad regime, including in prison.

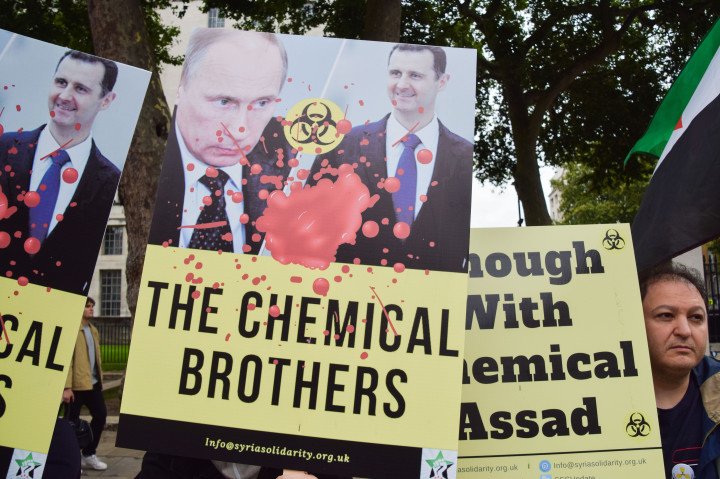

The regime is subjecting political prisoners to systematic torture and is responsible for numerous chemical attacks on civilians, including in Ghouta in 2013, that killed over 1,700 people at once.

France issued an arrest warrant against him in 2023 for the use of chemical weapons.

If Russian dictator Vladimir Putin could afford to help Al-Assad troops on the ground in 2015 after freezing the conflict with the Minsk-2 agreements, ten years after, the configuration has changed.

Russia can hardly help Assad, according to Nikola Mikovic, a journalist and researcher covering Russia’s foreign policy.

Moscow is stuck in Ukraine and ”cannot send serious reinforcements to its military contingent in the Middle Eastern country either,” Mikovic wrote in a Lowy Institute analysis.

Since the murder of Yevgeniy Prigozhin, the late head of mercenary company Wagner, the group has been dissolved in Russia’s Rosgvardia and the (unironically-named) Africa corps, with some units reportedly deployed in Kursk in August 2024, according to the Institute For the Study of War.

Still, Russia is reportedly sending mercenaries from the Africa Corps to reinforce its troops in Syria, the Ukrainian military intelligence agency (HUR) claimed on Dec. 3.

“The arrival of fighters – probably from the so-called ‘Africa Corps’ – is expected," according to the HUR.

It’s hard to estimate the number of Russian soldiers or mercenaries currently fighting in Syria since official figures have never been disclosed.

Putin mainly deployed his air force in Syria, and according to Deutsche Welle’s estimates, between 2,000 and 4,000 soldiers were additionally deployed.

Russia’s main strategic footholds in Syria are the naval base of Tartus and, further north, the Hmeimim Air Base, from where it gained access to the Mediterranean Sea.

Aaron Zelin, senior fellow at the Washington Institute, told RFE/RL that losing the Tartus naval base, in particular, would be an "extremely huge loss for Russia” as it’s the country’s Russia's only warm-water port that it can use for its naval activities and power projection.

"Losing it would essentially cut Russia out of the core of the Middle East," Zelin said.

And Russia has reportedly started evacuating its Tartus naval base in western Syria, according to a report by the Institute For the Study of War published on Dec. 3.

This could indicate Russia "does not intend to send significant reinforcements,” according to the U.S.-based think tank.

"Russia will likely, therefore redeploy the vessels to its bases in northwestern Russia and Kaliningrad Oblast," on the Baltic Sea, the ISW wrote.

Meanwhile, according to Ukraine's Defense Intelligence, Russian soldiers withdrew from the Syrian city of Hama and started fleeing in the direction of Damascus on Dec. 2, yet another blow to Putin’s image in the Middle East.

International blow for Russia

The Kremlin has recently lost credibility with Armenia, part of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), Russia’s military alliance, for its inability to fulfill its protection needs against Azerbaidjan.

Armenia announced its withdrawal from the alliance in June 2024. Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashynian declared the suspension of its activities in the coalition on Dec. 4.

“If the CSTO does not have an area of responsibility in Armenia and cannot show this line, then the CSTO as an organization does not exist,” he said. “I think we have passed the point of no return.”

In Syria, the rebels’ advance lighting advance shows that the Kremlin can’t protect Bashar Al-Assad against renewed instability, according to Mikovic, let alone send a massive amount of troops on the ground at the moment, striking a blow to its international reputation.

Putin is facing a dilemma, as the end of Assad’s regime would weaken its strongman image among allies in the Middle East and across Africa, where Russia offers its services to autocratic regimes against guarantees of stability.

These guarantees often go hand-in-hand with war crimes committed on the civilian population by Russian mercenaries, with numerous cases of exactions committed by the Wagner Group over the past years.

What about Russia’s war in Ukraine?

Still, experts say the consequences on the Ukrainian front will likely be limited.

“So far, Russia’s regional setbacks are primarily tactical and of limited consequence for its Ukraine campaign,” Hanna Notte, the director of the Eurasia Nonproliferation Program at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, wrote in Financial Times.

Russia thought it could maintain the status quo in Syria with limited effort while invading Ukraine again in 2022, she wrote.

Still, the Kremlin learned “the hard way that frozen conflicts like Syria are frozen only until they are not,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, William Freer, a research fellow in national security at the U.K.-based think tank, the Council on Geostrategy, told Newsweek that “any level of Russian political, economic, or military bandwidth which is diverted from the conflict against Ukraine is beneficial to Ukraine.”

"The impact, however, will likely be extremely limited," Freer added, as “Ukraine is too important to the Kremlin."

-9377b86f9f8cd8a2b08f20ffd5f043e0.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-5568db4fb3d8644b8f1bf8244594bec1.png)