- Category

- War in Ukraine

How Russia Continues Committing Ecocide in Ukraine, from Chornobyl to Today

For decades, Russia has systematically destroyed Ukraine’s environment, starting with the Chornobyl catastrophe that threatened the entire continent with a nuclear disaster. As the latest oil spill in the Kerch Strait shows, Russia’s disregard for the environment threatens Ukraine with an ongoing ecocide, among the numerous war crimes the Kremlin is hell-bent on committing in Ukraine.

The Russian army has committed over 6,500 environmental crimes in Ukraine as of November 2024, Svitlana Hrynchuk, Ukraine’s Minister of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources, reported at the UN Climate Change Conference.

In total, the war destroyed three million hectares of forests. Mines contaminate 139,000 square meters of Ukraine’s territory, the equivalent of 23% of its territory, roughly the size of Greece.

The damage caused by the Russian ecocide is estimated at $71 billion so far. Ecocide is used as a weapon of war in Ukraine alongside the systematic destruction of the country’s civilian infrastructure and energy network.

Ukraine wants the overlooked crime of ecocide to be added to the International Criminal Court's (ICC) list of recognized international crimes, alongside genocide, crimes against humanity, aggression, and war crimes—Russia’s primary weapons of war.

Russia’s ecocide is bringing Ukraine to the brink of ecological collapse, according to the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe.

“Vast swaths of Ukraine are contaminated with landmines, toxic chemicals, and heavy metals,” the commission’s briefing reads. “Hundreds of thousands of square miles of agricultural land are decimated, groundwater contaminated, and nature reserves consumed by fire.”

Ecocide makes the country’s regions uninhabitable for civilian life, transforming them into a potentially toxic wasteland, a study published in The Conversation by researchers Renéo Lukic and Sophie Marineau said.

Destroyed dam: Nova Kakhovka

One of the most devastating, without a doubt, was the destruction of the Nova Kakhovka dam in June 2023, when the Russians blew it up, submerging 620 square kilometers of territory in the Kherson, Mykolaiv, Dnipropetrovsk, and Zaporizhzhia regions, impacting 100,000 residents.

The explosion destroyed the ecosystem in this area, killing a large number of fish, flooding over 11,000 hectares of forest, and causing the extinction of a significant portion of rare flora and fauna.

Greenpeace warned that the dam’s destruction caused the flooding of at least 32 fuel stations, warehouses, and oil refineries, potentially leaking chemicals, oil, and gasoline into the river’s waters and soils.

Satellite data analysis reveals that approximately 150 tons of motor oil leaked into the water in the initial days following the disaster.

Soils and water bodies could remain unsuitable for agricultural production and drinking water for many years, said Manfred Santen, a Greenpeace chemist from Germany.

This brutal ecocide could be added to the list of Russia’s war crimes following the destruction of the Khakovka dam, said President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in June 2023.

Killing endangered species

Russia’s military has set up a military base and a training site for newly mobilized soldiers on the occupied Arabat Spit, a strip of land occupied by the Russians that connects the eastern part of Crimea with Ukraine's mainland.

Russian soldiers also found a new way to entertain themselves between boring training: killing endangered white swans migrating to the Arabat Spit for winter “just for fun,” Kherson Region Administration advisor Serhiy Khlan reported in December 2022.

This is not the only reserve the Russians have decided to wipe out. In June 2023, the occupying troops decided to take animals from the Askania Nova reserve in the Kherson region and bring them to the Krasnodar Safari Park in Russia, effectively stealing the animals and destroying a unique reserve.

Some stolen animals died due to a lack of proper care, said the reserve’s director, Viktor Shapoval, the UACrisis media center reported.

In 2022, the Russians burned almost 1.4 thousand hectares of the reserve, according to the online outlet UkraineWorld. Military aircraft have been constantly flying at low altitudes over the protected area, causing wild animals to panic and die.

On the coast of the Kherson region, the Russians opened the Dzharylhach Island, home to rare bird species such as pelicans, waders, common eiders, spoonbills, and large groups of swans, for tourism and hunting.

Forests up in flames

Over two years of war, over 8,000 square kilometers of Ukrainian territory burned because of the ongoing fighting—including over 1,000 square kilometers of forests that went up in flames, Ukraine War Environmental Consequences Work Group (UWEC) reported in April 2024.

Russia has already destroyed almost 3 million hectares of forests in Ukraine, Zelenskyy said in November 2022.

Long-lasting fires destroy roots, grass seeds, bulbs, and corms in the soil, along with the animals that live in them, said UWEC.

Meanwhile, Russia’s brief occupation of Chornobyl’s exclusion zone in early 2022 cost Ukraine 22,000 hectares of burned forest, potentially displacing radioactive particles with smoke beyond the exclusion zone and over large distances.

A total of 44% of the most valuable natural reserve territories are in the war zone, under Russian control, or inaccessible to Ukraine, reported the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, quoted by Ukrainian NGO EkoDia.

Powerful fires damaged the Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, Askania-Nova Reserve, and all national parks in southern Ukraine.

Almost the entire land-based section of the Dzharylhach Island went up in smoke in 2023, UWEC reported.

“Absolutely every single one of the most important protected areas within the conflict zone has been damaged by fire,” the report reads.

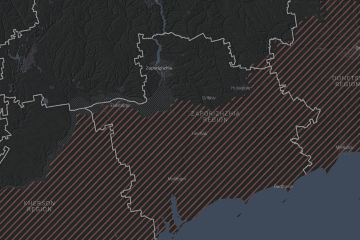

Flooded mines

Since the start of the conflict in 2014, Ukraine has lost control of around 80% of Donbas’ coal mines, according to an OpenDemocracy media platform report published in 2019, before the full-scale invasion.

The mines are increasingly flooded due to a lack of care or the industry's disarray.

More than 35 mines in the region were either in the process of flooding or had already totally flooded in 2017, according to a report by the OSCE’s Project Coordinator in Ukraine.

Mine flooding can lead to methane explosions in cellars, flooding of residential buildings, soil subsidence, and, of course, damage to infrastructure in the surrounding areas, OpenDemocracy underlined.

Mine water can pollute under and over groundwater with iron, chlorides, sulfates, other mineral salts, and heavy metals, directly affecting the region's drinking water quality, according to the same report.

Worse, the Oleksandr-Zakhid mine was contaminated by waste from the Horlivka chemical plant in the 1980s, while the Uhlehorska and Kalinin enterprises, two other mines, were used to store waste.

In 1979, an underground nuclear test was conducted in the Yunkom mine in Donetsk’s Yenakiieve district—and partial flooding might lead to the radioactive contamination of groundwater.

“This would have unpredictable consequences for natural resources not only in Donbas and other parts of Ukraine, but for the Black Sea Basin in general, and they will either be dire or really dire,” Ostap Semerak, former Minister for the Environment and Natural Resources, said back then.

However, if 30 to 40 mines potentially flooded in 2019, the number might be closer to 60 now, according to Yevhen Yakovlev, a hydrogeologist from the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, quoted by New Eastern Europe.

Donbas is now at serious risk of becoming “two-thirds uninhabitable” due to uncontrolled massive mine flooding, he said.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)