- Category

- War in Ukraine

Inside Ukraine’s Rapid Counteroffensive in Dobropillia—Before Facing Russia’s Meat-Grinder Assault in Pokrovsk

While Ukraine’s elite corps and regiments managed to contain a major Russian breakthrough near Dobropillia this fall, the battle further south in Pokrovsk has turned into brutal, close-quarters urban combat. Russia’s push grinds forward, but not without cost.

Dozens of soldiers sit in front of massive screens, divided into hundreds of smaller rectangles that cover the entire side of the room. This is their eyes in the sky, the livestream of hundreds of reconnaissance drones patrolling the sector, in search of any sign of the enemy’s infiltration.

“If even one Russian infantryman manages to sneak 5 kilometers into our rear and gets spotted, it immediately triggers an alert, as he can just stay there and send information about our positions,” says “Horik,” one of the commanders of an assault unit from the 1st Separate Assault Regiment.

“His presence alone can disrupt coordinated strikes—whether by drones, artillery, or other systems. We took some prisoners of war that stayed there quietly for up to 5 days, lying low and disclosing where we are.”

The labyrinth of corridors is used as a makeshift headquarters for the 1st Separate Assault Regiment, in charge of this sector northeast of the Donetsk region’s Dobropillia salient. The underground command center is a hive buzzing with frantic activity.

The soldiers crack jokes. Some shout orders into radios and computers via encrypted chats. They wait for the screens to flash red: this is the signal that a Russian has been spotted, and the hunt begins.

Even after months of “clean-up” operations, some Russian pockets still subsist here and there. Tens of small screens keep flashing red: the salient is still swarming with them, but the Ukrainians continue methodically eliminating them, one after another.

Further south, this tactic has worked: the city of Pokrovsk, with a pre-war population of 60,000, is now reportedly largely under Russian control, to the point that Russian troops were recently seen holding the Russian flag in the city center. But despite Kremlin claims of capturing multiple Ukrainian cities, including Pokrovsk and Kupiansk, President Zelenskyy and OSINT analysts have pushed back with battlefield data showing those areas remain contested and far from the sweeping victories Moscow reports.

Zelenskyy said Russia had concentrated around 170,000 troops—more than most European armies—in the area to capture the city. At least 25,000 Russian troops had been killed in October, most of whom were killed in the battle for Pokrovsk.

Russia’s potential takeover of Pokrovsk also threatens its twin city, Myrnohrad, roughly 7 kilometers east of the city.

“The situation in Pokrovsk is extremely difficult, but the Defense Forces continue to hold the northern part of the city, approximately along the railway line,” Dmitry Lykhov, Ukraine’s General Staff’s spokesperson, said. “Our units are also actively engaged in eliminating enemy cells.”

Meanwhile, up north, Ukraine announced on November 11 the completion of the Dobropillia operation, Lieutenant General Oleh Apostol, Commander of the Air Assault Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, said on national television.

“As of now, we have preliminarily completed our operation on the Dobropillia axis,” he said, adding that Russia was still attempting to attack Dobropillia using marines from the east and units of the 76th Division from the south.

Dopropillia defense: How Ukraine sealed the breakthrough

“The Russian offensive is still underway, and the enemy is going to bring in additional reserves in this area,” Lieutenant Colonel “Lemko,” 1st Azov Army Corps’ chief of staff, said.

In the 1st Separate Assault Regiment’s command center, a handful of commanders scribbles in red on a big map rolled out on a large table while debating where to deploy troops. The scene looks out of time in this era of drone warfare, but it’s a testament to the need to communicate for a successful operation.

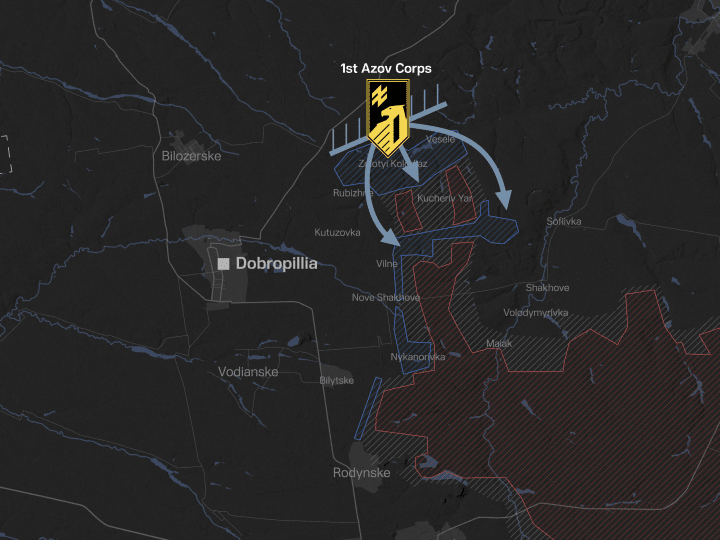

Coordination was key for Ukraine’s elite Azov corps when it was deployed in August this year to stop the breach in the Dobropillia direction.

The situation was critical, he recalled, as “the enemy had broken through the first line of defenses of the Ukrainian Armed Forces in that area,” threatening Dobropillia, Pokrovsk, and Myrnohrad all at once.

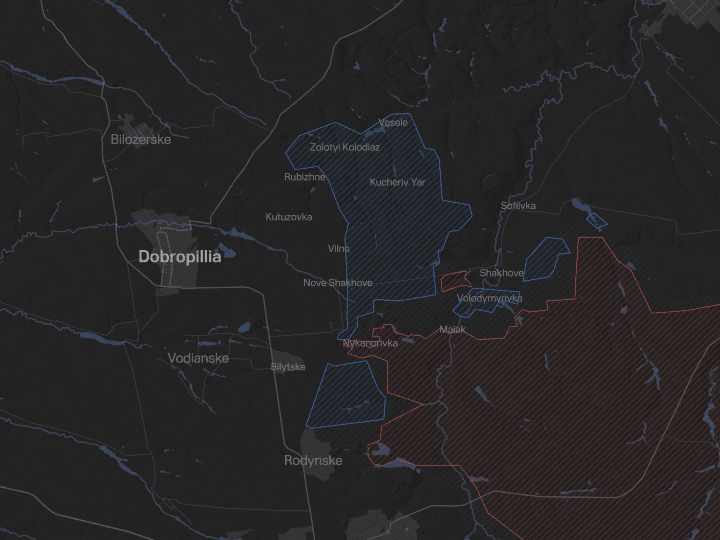

After a 15-kilometer-deep Russian breakthrough at the start of August, Ukraine scrambled Azov and numerous other brigades in a rapid-reaction operation to stop the bleeding that suddenly appeared on the Ukrainian open-source frontline tracker DeepState map, primarily due to local units' misleading reports and Russia’s ability to exploit a breach in the front.

“Azov united all units within the area and the sector,” Lemko said. “We sent our liaison officers to other units and command posts. We helped them, and sometimes they helped us; we all united to achieve this common goal.

Their first task was to establish blocking lines to prevent the Russian movement. “We stopped the enemy and established the final blocking line at Zolotyi Kolodiaz, along with blocking lines on the flanks,” Lemko said.

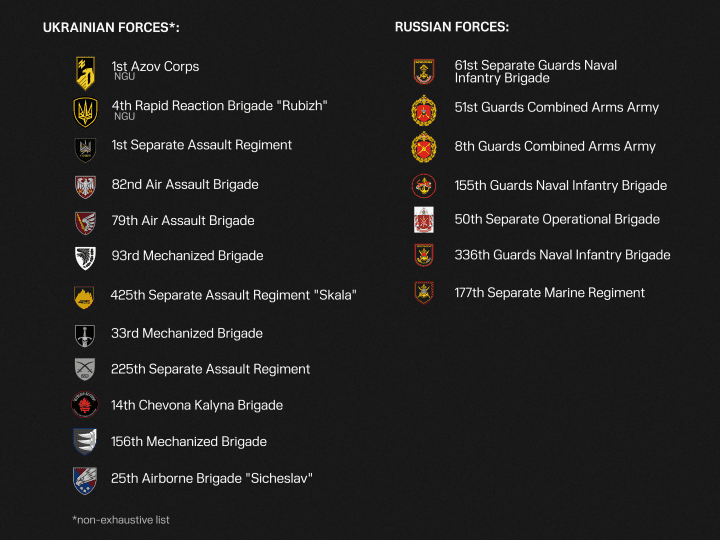

Ukraine had to swiftly deploy most of its elite forces to cut off Russia’s 51st and 8th Armies, supported by Naval reserves.

The 1st Separate Assault Regiment, led by its commander “Perun,” reportedly played a key role in cutting off Russia’s logistics from behind through a “pocket” tactic, systematically isolating Russian units, pinning them down, and then encircling them.

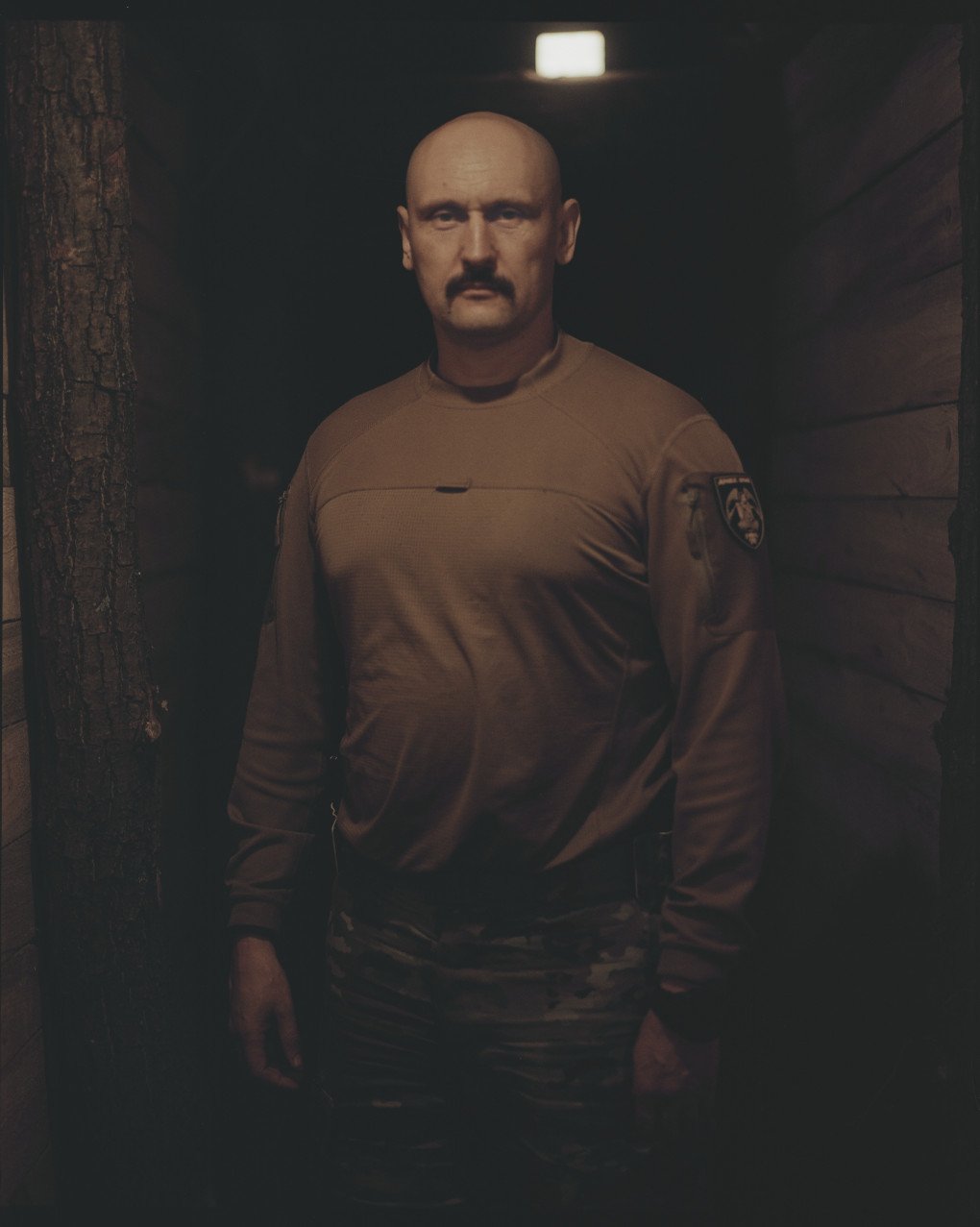

Dmytro “Perun” Filatov, the regiment’s commander, with his massive handlebar moustache, his shaven head, and the Ukrainian mace that has the pride of place on his war desk, could look the part of a 19th-century Cossack novel.

Judging by the screens and the order that reigns in this command center, where every wall is covered by carefully cut wooden boards, even behind a computer, his men are as deadly efficient as the tactic chosen to eliminate Russian pockets in the area.

“The regiment decided to split the operation into stages,” he said. “In the first stage, we cut off the flanks—the furthest salient—and carried out a comprehensive clearance of the settlements.”

The Russian forces remained in the wooded belts, and clearing there took longer, said Perun. “First, we blocked their advance in depth, then executed a second envelopment and severed the main ring,” he said. “Several assault units were involved—the 225th and our regiment, with the 425th Separate Assault Regiment operating slightly farther down.”

It was a complex operation, he explained, as some positions couldn’t be held, which is why the 1st Separate Assault Regiment initially advanced with mechanized brigades.

While the Russians concentrated on that mechanized thrust, they held the sector with small groups and “gradually destroyed or captured the enemy forces trapped in the encirclement.”

Throughout September, Ukrainian troops used a “pockets first” tactic to isolate and eliminate Russian groups around Pokrovsk and Dobropillia, with steady map gains confirmed by open-source analysts. From mid-September to early October, Ukrainian advances pushed back Russian units near Volodymyrivka, Shakhove, and Nove Shakhove, while minor clashes flared around Nykanorivka and Zoloty Kolodyaz.

By late October, Ukraine had crushed one of Russia’s biggest mechanized attacks near Shakhove–Volodymyrivka, and regained ground around Nove Shakhove.

Finally, at the end of November, Ukraine’s forces reportedly completed the “clean-up” around Dobropillia, eliminating Russian pockets and liberating multiple settlements across the front.

The adverse weather and the upcoming winter contributed to Ukraine’s localized success, said Lemko.

As the fourth year of Russia’s gruelling war advances, dropping temperatures and the lack of foliage leave little chance to any side eager to confront each other in an open terrain.

“When they entered these positions, the weather was warm. The temperature may fall to as low as eight degrees or lower during the night,” he said. “Their situation was deteriorating, and many of them have committed suicide without surrender, while some died of their wounds.”

However, the adverse weather is a double-edged sword further south, as the Russians have deployed additional troops to Pokrovsk, using the thick fog that hung over the city to their advantage, the 7th Rapid Response Corps reported.

The fog has hampered aerial reconnaissance, limiting visibility and preventing effective detection and targeting of troops.

“The enemy is trying to exploit poor visibility to amass forces, set up shelters in buildings, and prepare for a further offensive,” the report said. “In bad weather, they can bring more troops into the city.”

Close-combat in the trenches

Russians and Ukrainians have resorted to mirroring tactics in the area to deploy more troops: only small groups of two or three can move around and take up positions to avoid becoming easy drone targets, infantrymen from the 93d Brigade told UNITED24 Media.

“You have to have nerves of steel and serious stamina,” said Jean, a stormtrooper belonging to the brigade, while taking a break from his training in some abandoned quarry turned training ground.

“The enemy was sitting about 100–150 meters away,” said “Uncle,” Jean’s brother-in-arms. “The main thing for us was to spot them as fast as possible—they camouflaged themselves well,”

“We searched carefully for any signs. We were told the enemy would be in the last dugout, so we moved through the whole tree line, clearing every trench. There were dead enemy bodies everywhere—our guys had already hit them earlier,” Uncle added.

Infantrymen gamble with their lives more than any other soldiers—case in point, “Jockey” in the 1st Separate Assault Regiment.

Jockey is thin, and the kind of man anyone could meet in the cashier’s queue in the supermarket. Except that now he’s wearing Ukraine’s pixelated uniform and recently had to fight for his life.

“Our fighter, Jockey, got into hand-to-hand combat with the enemy,” said “Noah,” his commander. The entire crew saw the fight from a drone view, unable to do anything until they could finally take him out of the trench, hands burned and exhausted.

“He ripped the automatic rifle out of his hands bare-handed—burned his own hands,” Noah recalled, with a bit of pride in his voice. “Then—using the enemy’s knife in that close fight—stabbed him. ‘I killed him,’ he said afterwards.”

“He’s just an ordinary person, not some professional military guy,” said Noah. “He used to work at a factory. Killing an enemy in hand-to-hand combat is something else; many people’s psyches shut down, and they go into shock. But he stayed focused—a real champ.”

Noah was himself storming trenches before becoming a commander. A former policeman, he recalls how fear can sometimes take over a man, and how he overcame it.

“Fear is always here,” he says. “Never believe a soldier who tells you he’s not scared. Training helps a lot. To keep you breathing, to think in action. This is what we’re trained to do, to think.”

Assault troops had to add gas masks to their kits to survive chemical attacks. As if FPVs, shellings, and enemy assaults weren’t enough.

“When we’re holding positions, the enemy often drops gas on us — trying to smoke us out of the trenches,” said LM, one of the 93rd Brigade’s men training for his next assault. “They use chemicals, gases, anything they’ve got. The fumes and burning munitions can also cause internal burns.”

Such stories shouldn’t overlook the fact that Ukraine faces major mobilization issues.

After almost four years of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine struggles to refill its ranks against an enemy that keeps filling theirs, with salaries of up to $2,700, a sum unheard of in rural Russia in exchange for a certain death on Ukrainian soil.

The brutal war of attrition going on in southeastern and eastern Ukraine sees the constant threat of death from above. In this war, drones are cheaper than a man’s life.

Getting to the position and leaving the position are the hardest parts, Jean added.

Drone Domination: Eyes in the Sky and First-Person Killers

“Everything’s buzzing,” Jean said.

We’re in a field, surrounded by men in balaclava and shotguns, just in case. This war has become more post-apocalyptic by the day, with columns of motley vehicles following each other and soldiers armed with shotguns in the back of pick-ups, just in case another deadly buzz comes around. But better be accurate.

“If a drone flies to us, how long do we have?” we ask, in the back of a pickup. We’re feeling safe so far, surrounded by a Mad Max-looking escort.

A flashy green quad is in front of us, preceded by a few hillbilly trucks. On top of all of them, anti-drone antenna and soldiers holding shotguns, one hand on the car and eyes on the sky.

“It all depends on how far away it is,” one of the men, holding his shotgun close to him in the back of the pickup where we stand, tells us. “If it’s far, you don’t need it (a shotgun—ed)—it won’t work. If it comes up closer—say, about 15–20 metres—the shotgun is effective, very effective.”

Going from point A to point B has become increasingly deadly over the past year. The Russians expand the kill zone every day with longer-range fiber-optic and first-person-views (FPV) constantly patrolling the sky, transforming the front line into a fluid, large swath of virtual no man’s land for the infantry and for journalists trying to cover the conflict.

Since the Russians have developed fiber-optic drones that are virtually undetectable, the Ukrainian side has had to develop its own. This is what the 93rd Brigade is working on: drones that, for once, copy the other side, but with bigger and more lethal charges.

Fiber-optic drones are the new counterpunch: their wired link makes them impossible to jam, letting operators strike with precision, but at the cost of reduced freedom of movement, since the cable can snag.

“Omar,” one of the commanders of the famed 93rd Brigade, is proud of presenting us their new baby. He has an easy laugh that goes well with his colossal beard, especially when he shows us on his phone each one of the columns the Russians tried to breach Ukrainian lines with.

Spoiler alert: In the video, the hedgehog-looking monsters turn back or explode.

“As soon as we increased our drones’ range by 3–4 kilometers, our strike zone expanded,” he said. “You can see the results: in a single day, we destroy up to 20 units of enemy equipment and infantry columns, and we disrupt their logistics.”

But that’s not even the best part. “We can now reach their artillery lines—we destroy their artillery and stop their supply routes.”

In the meantime, adding to the difficulties, over the past year, a recent unit appeared to do much damage among Ukrainian forces: Rubicon — Russia’s new weapon in the sky, an elite unit specialized in drone warfare, striking with precision and speed across Ukraine’s front lines.

The unit has become the Ukrainian forces’ nightmare, due to its ability to scale up innovation copied from the battlefield.

“Rubicon is a centre for investigative development that operates like an institute. They train and scale,” Vovchik, a commander in an Azov drone unit, told us. “Because of that, they don't take somebody from the street; generally, they pull leads from across the whole army.”

“They use the 'thousand-cuts' method,” added Auda, a babyfaced pilot in the same unit, while flying a Vampire drone. “For example, hit the logistics routes so we can't deliver water, rations, and ammunition, then hit the dugout we're sitting in.

Rubicon does as much damage as possible so that it becomes impossible to conduct combat operations, Auda said.

Winter Warfare: The Next Frontlines

A single trip along the desolated roads of Ukraine’s East offers a bleak hellscape. Houses that used to be full of hope opened in half, smoldering ruins, a few civilians here and there on a bicycle with a 7-liter empty water bottle trying to get by until the next gliding bomb falls around.

Whether it is in Kostiantynivka, Pokrovsk, or surrounding Dobropillia, the landscape is the same painful repetition of the desolation that reigns in Bakhmut, Avdiivka, or Toretsk.

An army of ghosts hiding from another one, hiding in basements, still clinging to the remnants of the place they once called home, hoping the next Russian hit won’t be for them. Almost 1,000 of them stay in cities like Pokrovsk, living in a purgatory, unable or resigned to the hell that’s coming for them, in the way of a Russian bullet or worse.

These are the places where the next fight will take place. Shattered windows, charred buildings, streets after streets.

Coffee shops where lovers used to meet will turn into graveyards where soldiers will meet their fate, between a broken barista-grade machine and a red star that’ll only glow on the medal received back home, with enough money to buy a Lada, for the sake of raising a Russian flag over a dead town where only crows will win their fair share of corpses.

Urban warfare is the worst, Noah told us.

“It’s tough to break through,” he said. “When the enemy fortifies there, it’s complicated to drive them out. But we’re gradually managing.”

“Until an infantryman goes in and makes the final shot to the head, no one else will do it. Where the infantryman sits—that’s considered our territory. If the area is empty, it means it’s not ours; it’s a gray zone. But once an infantryman goes in, digs in, and takes a position—that’s it, that’s our land.”

-29ed98e0f248ee005bb84bfbf7f30adf.jpg)

-0666d38c3abb51dc66be9ab82b971e20.jpg)

-f88628fa403b11af0b72ec7b062ce954.jpeg)

-051a89e5a5304a3f0a58cfb1746eda24.png)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-a68ec0e1961ffb8905a325650e6f0e3f.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)