- Category

- War in Ukraine

Sold for a Passport: Russia’s Recruitment Pipeline Sending Young Africans Into Its War

To offset mounting losses and dodge another unpopular mobilization, Russia is luring foreign recruits with more than money — passports, residency, and promises of safe, technical jobs. But once contracts are signed, many are sent straight to the front. Deception, not duty, is the cornerstone of this recruitment strategy.

Under a decree signed by Russian leader Vladimir Putin in January 2024, any foreign national who signs a one-year contract to serve in the so-called “special military operation ” becomes eligible for fast-tracked Russian citizenship.

It’s part of a broader campaign to fill the gaps in Russia’s battered manpower, and it’s working. Thousands of soldiers from approximately 50 countries are fighting for the Russian Armed Forces. Over 600 African nationals were fighting for Russia by mid-2024, according to the Russian investigative outlet The Insider.

Some were lured in with promises of jobs or education. Others, like Zambian student Lemekhani Nathan Nyirenda, were pulled straight from prison. He died in Ukraine in September 2022, becoming the first confirmed foreign fatality of Russia’s war.

Not every foreign fighter is coerced. Russia has been conducting a wide-ranging recruitment campaign, targeting foreign mercenaries, particularly in Africa. Over the past decade, Russia has quietly built political, military, and media influence across the continent, casting itself as a counterweight to Western powers.

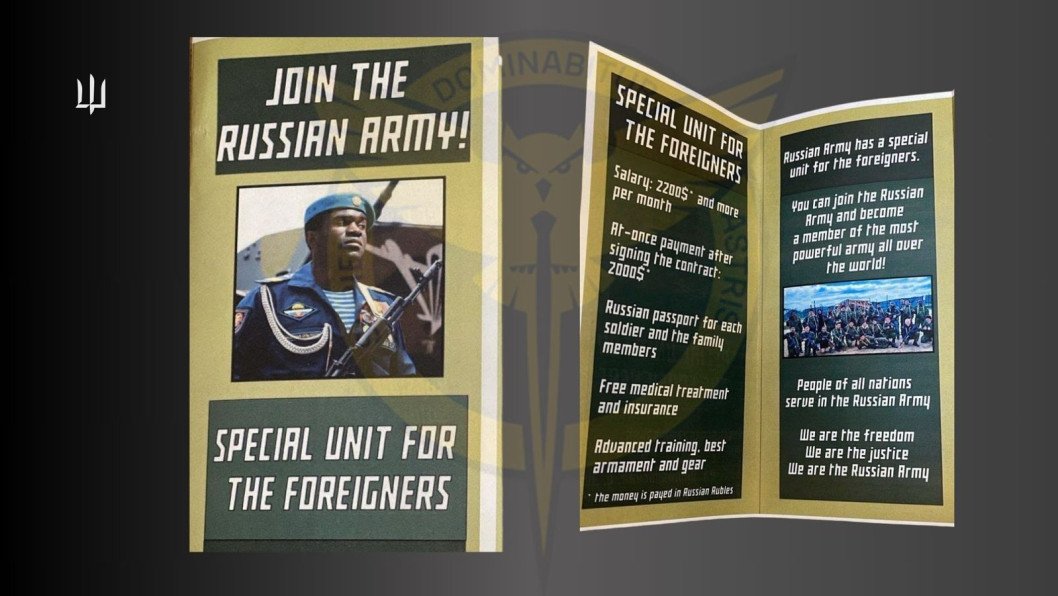

“The recruitment of Africans for their participation in ‘meat assaults’ on Ukrainian territory is carried out by a special unit of the Russian Defense Ministry,” reported Ukraine’s Defense Intelligence (HUR), adding that the initial cash payment promise can go up to $2,000 for signing a contract.

Few of these fighters ever make it back. Some are killed. Others –more fortunate– are captured. But what’s telling is how little effort Russia makes to get them home. Ukrainian officials say that over the past year, not a single African POW has been exchanged. Russia hasn’t asked for them back, and many of their home countries want nothing to do with them either, threatening criminal prosecution for mercenary activity.

One of the few governments to speak out is Togo’s. After several of its citizens were captured in Ukraine, including students who had arrived in Russia on scholarships, the country’s Foreign Ministry confirmed they were misled with promises of education and jobs. It urged young people to be wary of too-good-to-be-true offers—especially from Russia—and said it was working with partners to assist those affected. But like so many others caught in this trap, the students were left stranded: used by Russia, unwanted at home, and now facing war crimes trials far from either.

“I planned to study medicine.”

Koulékpato Dosseh left Togo with a dream: to become a doctor. Russia was supposedly a fast and affordable way to study abroad, especially after his visa applications to Canada and France were denied. But within months of landing in Saratov, that dream began to fall apart.

Dosseh is currently a prisoner of war held in a Ukrainian detention center. He agreed to speak on camera voluntarily and stated that he was not under duress during the interview. However, it is important to note that his story cannot be independently verified.

He studied for just one month. Then came the paperwork delays, the dormitory backlogs, and the growing sense that without legal residency, he’d be forced to return home. That’s when someone he calls a “brother”—a fellow African already serving in the Russian army—offered a different path: a job in law enforcement that came with papers.

Instead, Dosseh found himself signed up for war.

“They told us we were just going to ask for information,” he said. “But we didn’t understand anything—we don’t speak Russian. That same day, they made us sign a contract. Only later did we find out it was a war contract.”

Dosseh was sent to the front line with almost no training. He didn’t speak the language, couldn’t read the documents he signed, and had never held a rifle before arriving at boot camp. He was told he would be used in a support role. Instead, he was deployed into an active assault unit.

His first mission was also his last. Within 20 minutes of contact, four of the six men in his squad were dead. He crawled through snow, hid in an abandoned bunker, and played dead under tree branches to avoid drones. By the time he surrendered to Ukrainian soldiers, he was seriously wounded. His legs no longer work. Ukrainian doctors have warned that they may need to be amputated.

Now, Dosseh sits in a Ukrainian detention center, awaiting trial. He is not considered a lawful combatant under international humanitarian law and may be prosecuted as a mercenary. He has had no contact with Russia, and believes his family back in Togo thinks he’s dead.

“I regret everything,” he says. “I don’t even know if it was my fault or my fate. But I regret it.”

His story, as Ukrainian MFA spokesperson Heorhii Tykhyi put it, is not unique. Russia is targeting undocumented African students and workers—those at risk of deportation—with promises of work, legal status, and even citizenship. In reality, many are thrown into frontline roles with no training and no way out.

“It felt like they were sending me to be sacrificed,” Dosseh says.

How Russia exploits Africans without papers

Of the many cogs in the Russian war machine, a campaign to fill its ranks with false promises and coercion is underway. Across the country, African nationals are being sent into military service through a system that relies on desperation, deception, and legal limbo.

Many arrive in Russia as students or migrant workers, drawn by promises of affordable education or under-the-table jobs. But once their visas expire—or if they get caught in one of Russia’s mass police raids—they lose all protection. Without legal documents, they can’t work, study, or even rent housing. And that’s when the recruiters move in.

Richard Kanu from Sierra Leone paid heavily for a Russian visa, only to end up near death in the war, lured into Russia’s large-scale recruitment program targeting Africa and Asia. pic.twitter.com/tnRbiWE91g

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) December 15, 2024

Russia has turned the threat of deportation into a recruitment tool. In one documented case, Gambian national Lamin Jatta was arrested and told point-blank: sign a contract with the Russian Ministry of Defense (MoD) or get deported. He was later killed in Ukraine. Others were offered “a way out” of detention centers if they agreed to join the army.

But coercion isn’t the only tactic. Russia is also offering carrots. A decree signed by Putin in January 2024 grants any foreigner who signs a military contract for at least one year during the so-called “special military operation” the right to fast-track citizenship.

Another of the insane recruitment videos Russia is using to lure African women to Russia to slave in factories assembling kamikaze drones.

— Jay in Kyiv (@JayinKyiv) April 27, 2025

From the "Alabuga Start Program" Telegram channel. pic.twitter.com/eXLnxHdjz9

Women aren’t spared either. According to an investigation by the Insider, hundreds of young African women were reportedly brought to Russia under promises of hospitality jobs or scholarships, only to find themselves assembling Shahed drones at a military factory in the Alabuga Special Economic Zone. They described 12-hour shifts, toxic exposure, withheld wages, and guards who made sure they couldn’t leave.

It’s a pipeline. African nationals enter Russia legally. Many lose status due to bureaucracy, poverty, or scam employers. Then, the state or companies with military ties find ways to funnel them into the war effort. Some end up in uniforms. Some end up in weapons factories. Most end up with no way out.

And when they’re wounded or captured, like Dosseh from Togo, they’re left behind. Russia doesn’t claim them. According to some African POWS, their home countries can be slow to intervene. Many of these individuals face criminal prosecution for their mercenary activity in their home countries.

As Ukraine continues to document and detain foreign POWs, cases like Dosseh’s are becoming harder to ignore. These aren't isolated incidents. They're part of a pattern. Russia has figured out how to turn undocumented Africans into expendable assets for its war—and no one is really stopping them.

Russia's Africa Corp

In early 2025, the Kremlin quietly launched a recruitment blitz for its secretive military venture abroad: the Africa Corps. Ostensibly billed as a stabilizing force to expand Russia’s presence on the continent, the Africa Corps is a Ministry of Defense-controlled initiative that mirrors everything the Wagner Group once was, minus the name and the headlines.

Russia intensified recruitment for the Africa Corps in February 2025, the US-based think tank Institute for the Study of War reported. Regional recruiters, like those in Tatarstan, began flooding social media and local media outlets with flashy offers: six months of training in Russia, followed by deployment to Africa, and receiving generous bonuses and salaries far greater than what's available for the average civilian.

Those who signed up were promised generous state benefits, including payments for children and injury compensation. But the fine print—usually buried or omitted—made it clear that these contracts were with the Russian Ministry of Defense. And if Moscow decides, these men can be redeployed to Ukraine.

One local recruiter in Russia’s Tatarstan region confirmed it bluntly in April: while the Africa Corps is officially intended for operations on the continent, fighters are obligated to go wherever the Russian MoD sends them. In practice, that often means Ukraine.

This isn’t a peacekeeping mission. It’s a reserve pool, dressed up with Pan-African branding and vague promises of overseas adventure. The actual aim is twofold: keep Russia’s military footprint in Africa intact after Wagner’s public collapse, and quietly build up manpower reserves that can be redirected to Ukraine if needed.

The structure of Africa Corps—its salaries, contracts, and command hierarchy—is a carbon copy of Wagner’s post-2014 playbook. Recruits train on Russian soil, deploy to places like Mali, the Central African Republic, or Burkina Faso, and operate under the guise of bilateral agreements with pro-Russian regimes.

In an interview with UNITED24 Media, Candace Rondeaux, a senior fellow and Wagner expert, put it plainly: “Wagner’s operations in Africa have been integral in ensuring that Russia can continue to operate despite the sanctions that have crippled its economy.”

In return for propping up unstable regimes, the Kremlin gets boots on the ground, access to arms routes and mineral deposits, a foothold in geopolitically strategic territory—and a steady pipeline of fighters it can call up when the frontline in Ukraine gets thin.

Meanwhile, the idea that this is a strictly Africa-based force is a lie. Recruiters are clear: if the order comes from above, the front line in the Donetsk or Kharkiv regions could be next. Just like Wagner, the Africa Corps is Russia’s way of extending its war by other means, and testing how far desperation, economic coercion, and propaganda can stretch a soldier’s contract.

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)

-1afe8933c743567b9dae4cc5225a73cb.png)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)