- Category

- War in Ukraine

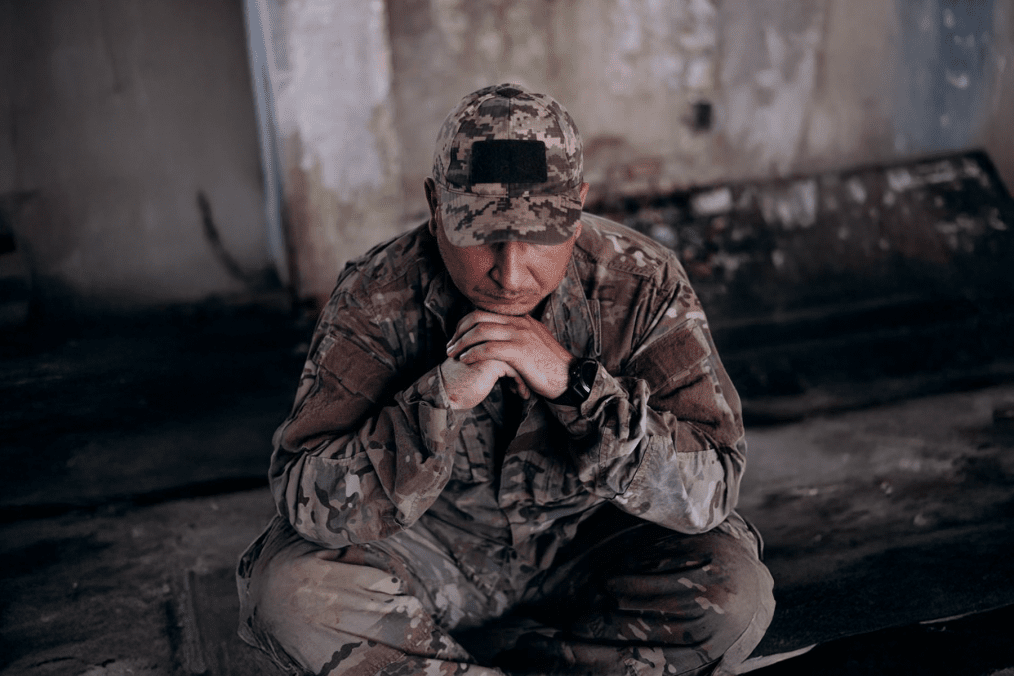

The Philosopher in a Flak Jacket: What Can a Stoic Soldier Teach Us About Surviving Modern War?

Deep in a dugout near Ukraine’s front lines, a soldier sits with a book. It is not a tactical manual or a thriller, but Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations. His call sign is Stoic, and he lives by this philosophy.

Stoic serves in the “Black Swarm” strike drone company of Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Brigade. Before the full-scale war, he studied history and museum studies and had plans to go into business. But after February 24, 2022, everything changed.

“I volunteered,” he says calmly, as if he weren’t describing one of the most pivotal decisions of his life. “It was March—I sent my family to the west of Ukraine, where it was a bit safer, and went to the enlistment office myself. A few days later, I was already in the brigade, even without basic military training.”

His unit has since carried out missions in Toretsk, Kharkiv, Lyman, Bakhmut, and Chernihiv. Before joining the drone team, Stoic served as a machine gunner in reconnaissance. He remembers his first combat mission vividly—when he realized he needed to learn how to manage his emotions.

“We went on a recon mission into the gray zone,” he says. “It was right after my birthday—I had just turned 30. An enemy drone was flying overhead, so we tried to hide and dig in. At night, we suddenly heard voices—the enemy’s observation post was just 15 meters across a narrow river. And their flank was already on our side.”

His imagination kicked in instantly: the Russians would find them, kill or capture them. They’d been out all day, drenched in sweat, and the September nights in Kharkiv were cold.

“I thought: if I get out of this, I’ll go to my commander and say I’m done—I’ve had enough, send me to the rear,” Stoic admits.

Adding to the tension, their comrades—whose sector they were crossing—hadn’t been informed of their movement. It was only thanks to the soldiers’ composure that friendly fire was avoided.

“When we got out, I realized I needed to build some kind of resistance to these panic attacks,” says Stoic. “I started working on my passions, my excessive emotions. Then, something happened that showed me the way.”

Wounded in action

“I was near Bakhmut in November 2023. We had to move from one position to another, hold it, and wait for reinforcements. I was the last in line. When we were about a kilometer away, an enemy bomber drone hovered over us. I moved left—it followed. I moved right—it followed. It was tracking me. So I made a decision to run in the opposite direction from the group,” he says, almost dispassionately.

The drone chased him. A grenade dropped, wounding him in the arm and back. “Luckily, my legs were untouched, so I could keep moving on sheer will,” he says. But the drone didn’t stop.

“I fell into a trench, looked up—another grenade. The first blast knocked the strength out of me. I don’t know, maybe it was grit, but I ran—the second explosion went off to the side. I started crawling out, and then the guys came to help. I was lucky. A year earlier, I’d managed to get Kevlar neck protection. One of the fragments got stuck in it. Without it, I’d be dead,” Stoic states bluntly.

While recovering in the hospital, he stumbled upon Meditations by Marcus Aurelius.

It was like meeting myself. I saw my own thoughts on paper—only systematized. That’s when I realized there was a philosophy that not only gave meaning but also practical support—even in a trench, even under fire.

Stoic

Drone operator at Ukraine’s “Black Swarm” Territorial Defense Brigade

Later came a three-month course with Ukrainian philosopher Oleksandr Poltavtsev, and a deep dive into the ideas of Seneca, Epictetus, Zeno, and others. Stoicism became not just solace but a shield.

“I’ve always been drawn to living according to reason,” says Stoic. “When I read that stoics value wisdom, courage, justice, and moderation, it felt like an inner sigh of relief. That was it. That was my path.”

A citadel of the spirit

Stoicism teaches how to live rightly and be happy—to act with reason rather than emotion, and to choose what is good.

“I don’t suppress my emotions,” says Stoic. “I just don’t let them control me. Stoicism isn’t about being cold. It’s about staying in control so you don’t make mistakes in moments of weakness. I always remember Cleanthes’ quote: ‘Fate leads the willing and drags the unwilling.’ I chose to walk on my own.”

One Stoic idea—Amor fati, love of fate—says to accept everything with gratitude. But how do you accept shelling or wounds with gratitude?

“Of course, I’m not thrilled by the enemy’s actions,” says Stoic. “It would be wrong to say I’m grateful they’re trying to kill me. But Stoicism helps me stay calm. Whatever happens, I try to take something useful from it. Stoicism builds an inner citadel of the spirit. No matter the circumstances, that spirit doesn’t let even the worst events change who you are. You remain who you’ve shaped yourself to be, not who the situation wants to make you.”

Service, Stoic says, is a great place for refining oneself. Philosophy helps him strive toward a better version of himself. And military challenges test the virtues and values he fights for.

“There are many things I can’t control, like when the war will end,” he says. “But I won’t complain about that—it’s irrational. I accept both the negative and the positive sides of reality. If I can’t change the situation, I don’t worry about it. I focus on the areas where I can influence things.”

Sharing his knowledge

“In the Serebrianskyi Forest in 2023, we were under heavy shelling—six hits per minute. Every day. One day, a soldier from a neighboring unit jumped into our position in a panic, yelling that we had to run or we’d be wiped out. I was close to panicking myself, but I told him we were in a safe spot, below ground, and if we ran, bullets or shrapnel would definitely catch us. Eventually, he calmed down. We overcame our panic—because where there’s panic, there’s no reason.”

Visualization, Stoic says, often helps him prepare.

“Between missions, I’d constantly think about how I’d react to different scenarios: shelling, drones, injuries. That helped,” he said. “Even when I got hit, I made the right decisions—distracted the drone from the group, didn’t wait for another grenade, ran, told the guys I was wounded, asked them to take my weapon and pack. I didn’t lose my mind.”

Another core belief of this philosopher in a flak jacket: always do a bit more.

“In the army, you often hear, ‘That’s not how it’s done.’ I say: Maybe it’s not, but it can be—and it would be right. Don’t shirk responsibility—do more than expected. Not for praise, but because you can.”

In April 2024, Stoic decided to do a bit more to share his values. He launched a Telegram channel called “Stoic,” where he shares personal stories from the front, analyzed through the lens of philosophy. It now has over 10,000 subscribers and a unique community.

“People say it’s a calming space. One subscriber commented, then wrote again an hour later, asking: ‘What kind of channel is this? Why hasn’t anyone insulted me? Everyone listened and responded politely with arguments!’ There’s a certain atmosphere of respectful conversation here—and I’m glad for that.”

Many Ukrainians find support and answers in the channel—ways to stay grounded amid endless shelling and loss. Around the world, people are searching for something solid to hold on to. Perhaps a soldier-philosopher knows a bit more about that.

“We need to build inner anchors, not external ones,” says Stoic. “Don’t attach yourself to material things. And—though this may sound strange—not even to people. Love them, respect them, be friends, start families. But your inner foundations must be yours. If you lose something or someone, it’ll affect you less. Distinguish what you can control from what you can’t. Wisdom, justice, moderation, and courage—these are the core inner virtues. And if, God forbid, something happens, they won’t leave me unless I choose to give them up.”

The channel also supports his unit, bringing in over $32,000 in donations in its first 10 months.

Stoic continues to fight and write. He doesn’t yet know what he’ll do after the war, but he might walk thousands of kilometers on foot.

“The war tested me, so I’ll test myself with a journey,” he says. “Then maybe I’ll go into business. I want to make society better and the country stronger. In any case, I’m not a soldier who happens to love philosophy. I’m a philosopher who had to fight to defend his values.”

-35249c104385ca158fb62273fbd31476.jpg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-206008aed5f329e86c52788e3e423f23.jpg)