- Category

- War in Ukraine

The Strategies and Challenges That Could Decide Ukraine’s Fight in 2026

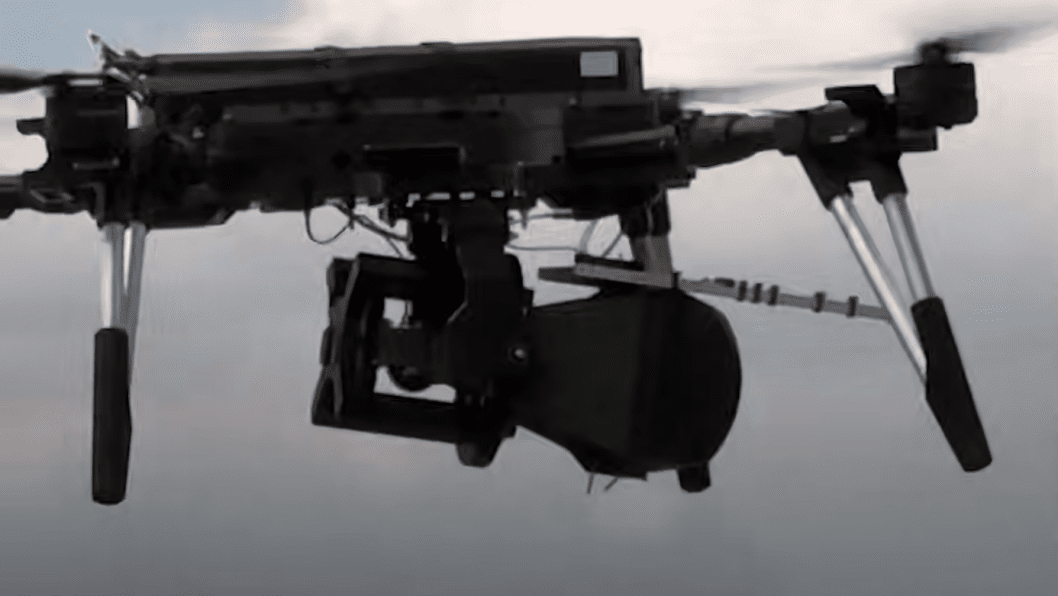

While Russia outmatches Ukraine in military size and industrial weight, Ukraine’s resistance has endured for nearly four years thanks to the ability to stay technologically one step ahead, building tools that replace soldiers in the most dangerous places. That edge is now being challenged as Russia adapts faster and scales wider. Which technologies may define Ukraine’s fight next year?

As the year winds down, events across Ukraine are pulling together the people who are trying to outline what Ukraine will need to hold that line in 2026. UNITED24 Media spoke with engineers, frontline commanders, and high-ranking officials shaping those discussions.

Four themes stood out:

Reinforcing air defense

Recruiting foreign engineers

Managing manpower shortages

Fixing the coordination gap between the military and private industry

Experts say Ukraine is at a critical juncture, and the country's resistance lies in its ability to find a solution.

Strategic view

Much of the battlefield has been reshaped by drones and precision munitions; this may be the case in all future armed conflicts. Tanks and heavy vehicles, once the spearhead of conventional land warfare, are now slow-moving targets and often rendered useless or, at best, operate with various configurations of “drone cages”.

At a defense tech event held in Ukraine, a high-ranking officer in Ukraine’s military offered a blunt forecast for the coming year. Ukraine has reached parity with Russia in drone numbers, he said, but remains behind in missiles and air-defense systems, as the country lacks the industrial base and engineering knowledge, specifically surrounding radars, to create its own systems.

“In the near future, we won’t have the technology to compensate for Russia’s advantage in resources,” he said. The only answer is innovation that “keeps people alive and builds an actual ability to fight further.”

The next phase of this war, the anonymous officer argued, will depend on how quickly Ukraine can redirect its resources, which are currently focused on churning out around 4 million drones a year, toward rocket and missile production to expand its air superiority.

Matching Russia’s near-total war tempo remains a struggle. A big topic of discussion was Moscow’s Rubicon unit. “Our deficiency is that we do not have a systematic approach—something like Rubicon, which can test and scale technology quickly.”

The officer, whose name is withheld for security reasons, says that Ukraine’s defense ecosystem, which operates under a free market system, must begin to operate as a single structure. “Private industry needs to join in the defense of Ukraine’s sky, integrate with current capabilities, and at the same time create new systems.” He says strategic industries must decentralise, protect themselves from strikes, and be able to produce even under bombardment. Small advantages matter. “Every advantage, no matter how brief, keeps our people alive.”

Protecting the sky

Ukraine’s airspace has become one of the most dangerous in the world. Hundreds of Russia’s aerial threats–a constant mix of drones, missiles, and gliding bombs terrorise the country day and night. Ukraine counters this with a patchwork of air defense systems, including Patriot batteries, mobile fire groups, and new interceptor drones. While they find relative success in shooting down threats, Russia is constantly adapting its approach.

“We shouldn’t rely only on interceptors,” says Oleksandr “Zhan” Vorobiov, head of air-defense training for the Third Army Corps. “We need mobile groups for low-flying Shaheds, interceptors for mid-range targets, and small, cheap rockets for the fast ones (reactive drones). Only a multi-layered system works.” Vorobiov offers a solution: an echeloned system that covers threats at every altitude.

However, such a system depends on something Ukraine still lacks on a large scale, he says: radars. “The rocket itself is simple—a solid-fuel engine and a camera,” says Vorobiov. “The real problem is detection.” Before 2014, Ukraine relied heavily on Soviet-made radar systems. Many were destroyed early in the invasion, leaving coverage gaps that Russia continues to exploit. New 3D radars are arriving from partners, and domestic production is slowly increasing, but not at a fast enough pace, he says.

Regarding what's outside Ukraine’s airspace, there is a need for longer-range strike capabilities. Artem Bielenkov, chief of staff of the 412th Nemesis Regiment, said 2026 will be “the year of aerial intelligence and the scaling of deep and middle-range strikes.”

Bielenkov’s unit coordinates with over thirty small manufacturers that supply the various hardware needs of his unit. “If you have a big challenge, then you have the innovation,” he said regarding the current state of Ukraine’s defense tech industry. “But we don’t need something that arrives six months late when it’s already obsolete.”

His complaint encapsulates a systemic problem in procurement: by the time drones reach Ukrainian units, Russia may already have developed countermeasures. This lag pushed brigades to build their own R&D labs, modifying equipment on the spot to fit battlefield needs. Meanwhile, Russia’s centralised structure and UAV units like Rubicon—which can test and deploy new drone designs within weeks—allow it to shorten its design–deployment cycle.

This design–deployment cycle is exactly what Ukraine’s defense advocacy group—Tech Force in UA (TFUA)—is trying to fix. TFUA’s executive director, Kateryna Mykhalko, said closing that gap requires more than new ideas; it needs long-term contracts, stable procurement rules, and clear testing standards. None of that is possible, she noted, unless the state and private sector finally start working in sync.

The manpower gap

Ukraine enters 2026 after two years of heavy mobilisation with what senior officers say is a shrinking recruitment pool and a frontline that is increasingly difficult to sustain. “We do not have infantry. Period,” said Andrii Onistrat, a senior officer in the Command for Unmanned Systems and a former commander of the Dovbush Hornets. “Whoever controls the drone kill zone will have the advantage.”

The Ukrainian Armed Forces are leaning heavily towards automation to compensate for the shortfall in soldiers. Rather than filling trenches with people, brigades are building dense networks of sensors, drones, and electronic-warfare tools. The idea is that machines cover the same territory with far less human cost.

Unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) are one area of rapid expansion. “If we have drones in the air and at sea, we’ll soon have them on the ground,” said Oleksandr Yabchanka of the Da Vinci Wolves battalion. “UGVs are being tested for logistics runs, reconnaissance, and even casualty evacuation. However, the main challenge for these drones is the harsh terrains that feature treefall, ditches, and rubble.

In tandem with machines, AI is becoming central to this transformation in doctrine. Ukraine already uses algorithms for target acquisition, but soon AI, and possibly a single operator, may be able to control swarms of FPV drones and launch combined-arms attacks. Vorobiov put it plainly: “In every part of the battlefield, even at command posts, we need to implement AI. It should work for us, not against us.”

Ukraine’s approach to developing drone systems, integrating AI, and making them usable in a battlefield full of electronic warfare, enemy loitering drones, and rough terrain will likely help offset the manpower shortage. In many ways, this is one of the few jobs people would actually be relieved to hand over to AI.

Military-led R&D and the push to finally coordinate it

Ukrainian defense tech has changed the way this war is fought. What started in 2022 as pure improvisation—guys in garages rewiring commercial drones, printing parts, salvaging whatever they could—has, four years later, become a respected and battle-tested ecosystem.

Western armies and venture capital firms are studying this war closely, and money is a valuable resource in war; however, the invisible hand of the free market is slowing Ukraine's progress. Companies need profit; armies need something timely and effective. Ukraine’s R&D cycle is faster than that of any NATO member, but it's still too slow for a war where Russia can deploy countermeasures to any available Ukrainian technology in weeks.

To keep pace, brigades built their own frontline labs and started reengineering everything they received. Viktoria “Tori” Honcharuk, a combat medic turned defense-tech lead in the Third Army Corps, told us: the shift was inevitable.

“Some brigades reworked 100% of the drones they received—nothing was ready out of the box,” she says. “Now we’re tired of redoing what private companies can’t get right. We’re building our own.” The third Army Corps proved the model works: one of its drone designs by the 21st Regiment of Unmanned Systems, Pavuk Dophina, was codified by the Defense Ministry and handed out to other brigades. Honcharuk puts it bluntly: “The military cares about victory, not profit.”

Opening the door to foreign engineers

Closing the gap between those fighting and those building is now the most pressing problem remaining. Ukraine might already be hitting the ceiling of its domestic engineering capacity, so brigades and startups are looking outward. Noah, an American engineer who co-founded Heron Precision , says the real bottleneck isn’t brains but structure.

“There’s a lot of fragmentation,” he says. “Our goal is to bridge those gaps so the operator in the trench has something that just works.” In his view, Ukraine’s problem isn’t finding volunteers; it’s getting the right people to the right task at the right moment.

That’s why foreign engineers keep showing up. Greg, a volunteer with Defense Tech for Ukraine , was tuning a UGV when we spoke. He said Ukraine has more room for outside talent than people think. “There is 100% space for people without military backgrounds,” he said, pointing to teammates who started as hobbyists—“one guy went from building guitar pedals to RF systems.” For him, the moral case is simple:

You can contribute by building machines that protect people; drone detection and anti-drone systems don’t necessarily kill anyone.

Greg

US Volunteer

New groups like the Snake Island Institute now match foreign specialists with Ukrainian units, speeding up fixes that would otherwise sit unsolved. Oleksandr Vorobiov, an air-defense instructor who recently mentored at one of the Institute’s hackathons, put it plainly: “Sometimes we fight with a problem for months, and a BMW engineer solves it in fifteen minutes.”

To most experts, Ukraine’s ability to stay in this war now depends on how well its private and public sectors can coordinate and adapt. New technologies appear every four to eight weeks, and the pace isn’t slowing. In a war increasingly fought by machines, the side that stops paying attention is the side that runs the risk of losing.

-457ad7ae19a951ebdca94e9b6bf6309d.png)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-0c8b60607d90d50391d4ca580d823e18.png)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-76b16b6d272a6f7d3b727a383b070de7.jpg)