- Category

- World

How the Houthis Became a Russian Asset: Human Smuggling, Stolen Grain, and Weapons Procurement

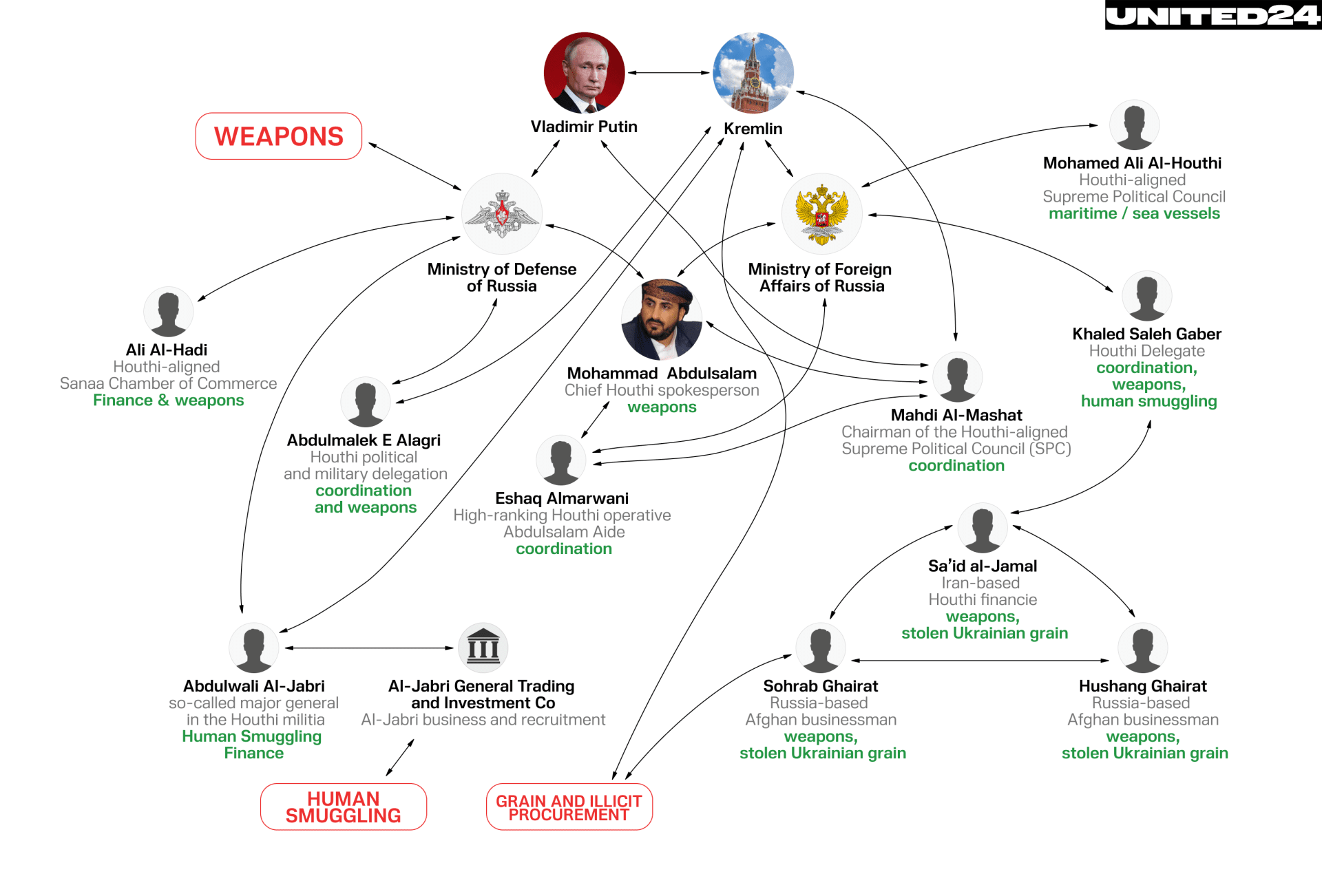

Russia has expanded its alliance to Iran-backed Houthis, a partnership that stretches beyond weapons into human smuggling, exploitation, and warfare. From the Red Sea to Ukraine, Moscow is outsourcing its war crimes to militias willing to trade lives for cash, weapons, and influence.

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Iranian-backed Ansarallah, commonly known as the Houthis, have been strengthening their military capabilities through their latest calculated alliance, Moscow. Recently, a deeper layer of the Houthi-Russia relationship has been exposed—one that goes beyond arms deals, to the exploitation of human lives.

Under the guise as a mediator and peace negotiator for Yemen’s conflict, Mohammad Abdulsalam, the chief Houthi spokesperson, has been travelling to Moscow, cementing the growing Houthi-Kremlin relationship.

Abdulsalam and six other high-ranking Houthi leaders were served with sanctions for weapons procurement and human smuggling operations.

The US designated the Houthis a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) in March 2025. After years of “fruitless diplomatic efforts,” international partners treated the Houthis as legitimate partners at the negotiating table, “only to be outplayed at every step,” the Atlantic Council reported.

A Houthi-affiliated operative and his company were also sanctioned for their human smuggling operation, recruiting Yemenis to fight for Russia in its war against Ukraine, while generating revenue to support the Houthis' militant operations.

For a movement that once claimed to be “independent,” the Houthis have instead become a tool of foreign powers, shifting from an Iranian proxy to a Kremlin asset.

The US further sanctioned a network of Houthi financial facilitators and procurement operatives in April 2025. The network received tens of millions of dollars’ worth of commodities from Russia, including weapons and sensitive goods, as well as stolen Ukrainian grain from Crimea, for onward shipment to Houthi-controlled Yemen.

Recruitment of Yemenis to fight for Russia

The Houthis are an Iran-aligned militant group that controls much of Yemen’s populous northwest. Since Yemen’s war began in 2015, a UN report estimates that more than 250,000 have been killed, over 80% of the 30 million population are now living in poverty, and thousands have fled the country.

Many Yemenis sought safety and employment across the border in Oman. Instead, they were funneled into a human smuggling scheme run by Houthi operative Abdulwali Abdoh Hasan Al-Jabri (Al-Jabri). Through his company, Al-Jabri General Trading and Investment Co (Al-Jabri Co), he promised vulnerable Yemenis jobs and citizenship in Russia.

In reality, recruits were sent to fight for Russia in its war in Ukraine, pushed to the frontlines after just days of training, according to investigative reporters. Their lives were sold for cash to fund the Houthis’ war machine.

Thousands of Yemenis are believed to have been recruited. Some have been confirmed dead. Many remain missing. Others are imprisoned in Russian camps, where they are exploited and forced to perform hard labor.

Yemenis who were recruited, speaking with investigators at Arab Reporters for Investigative journalism (ARIJ ), said that they were initially held in the Russian embassy in Oman. The recruiters said that they would only have their passports returned on the day of travel, and no backtracking was allowed.

A total of 38 Yemenis were on one flight to Moscow, accompanied by a Russian national. Once they arrived, they had their passports confiscated, and their phones closely monitored. They began training on rockets, landmines, and trench warfare but still had no idea they were recruited to fight. During, a medic told them that they were lied to, and they’d be sent to the front to fight.

Yemenis signed contracts with the military that they could not read or understand. Africans have also fallen victim to this recurring Russian tactic, coerced by job promises, but forced to “fill the gaps in Russia’s battered manpower”.

The contracts stated that they’d receive a much lower salary than agreed, and the recruiting company would keep the rest of the money, which was funnelled straight back to the Houthis.

Saleh al-Sammad, head of the Houthis' so-called Supreme Political Council, and the sanctioned Al-Jabri’s relationship dated back several years, say the investigators. Al-Sammad often visited Oman via UN and Omani mediation planes, which flew between Yemen's capital, Sana'a, and Oman’s capital, Muscat. This relationship is believed to be the beginning of the Yemeni human smuggling trade to Russia.

Ghanam Yahya, a Yemeni soldier sent to the Russian front in Ukraine, shot himself in November 2024 in protest against the mistreatment he faced by the Russian army, ARIJ reported. He, according to reporters, is one of several Yemenis to shoot themselves.

Who is behind the Houthis' weapons procurement from Russia?

Russia-based Afghan businessman Hushang Ghairat and his brother, Sohrab Ghairat, assisted al-Jamal with Houthi commercial initiatives in Russia, including arms procurement.

In the summer and autumn of 2024, Hushang and Sohrab, under Sa’id al-Jamal’s direction, orchestrated at least two shipments of stolen Ukrainian grain from Crimea to Yemen on board the Russia-flagged AM THESEUS, also known as the ZAFAR, the OFAC reported.

The network of those sanctioned in March 2025 is broad. Houthi spokesperson Mohammed Abdulsalam has played a central role in deepening ties with Moscow. He facilitated weapons deals and coordinated military support from Russia, meeting with officials at the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and arranging visits for Houthi delegations to Moscow.

His close aide, Eshaq Abdulmalek Abdullah Almarwani, has joined these high-level meetings, reinforcing the group’s diplomatic and military channels with the Kremlin.

At the political level, Mahdi Al-Mashat, head of the Houthi-aligned Supreme Political Council, has worked to expand direct cooperation with Russian leadership—including Vladimir Putin.

Houthi-aligned Supreme Political Council member, Mohamed Ali Al-Houthi, has ensured safe Red Sea passage for Russian vessels, linking the Houthis’ military leverage with Moscow’s strategic interests in global shipping routes.

Financially, Houthi networks have used shell companies and covert channels to secure Russian military equipment. Ali Muhammad Muhsin Salih Al-Hadi has led procurement operations, while Abdulmalek E. Alagri and Khaled Gaber have acted as key envoys, meeting with senior Russian officials and coordinating logistics through known sanctions-evading networks.

Russia’s Victor Bout back in the arms business with the Houthis

European officials anonymously confirmed in October 2024 that Russia was planning to carry out an illegal arms deal with the Houthis. Arms deliveries were thought to take place under the guise of stolen Ukrainian grain shipments .“When Houthi emissaries went to Moscow in August to negotiate the purchase of $10 million worth of automatic weapons, they encountered a familiar face: the moustached Bout,” the reports said.

Houthi representatives had traveled to Moscow under the cover of buying pesticides and vehicles, and visiting a Lada factory.

Russia’s Viktor Bout, known as the “Merchant of Death,” spent decades fueling global conflicts with Soviet-made weapons, making him one of the world's most prolific international arms dealers and, according to Michael Braun, the former chief of operations for the US Drug Enforcement Administration, “one of the most dangerous men on the face of the Earth.”

Just two years after being released from a lengthy US prison term, in a prisoner exchange, Bout was trying to arrange the sale of small arms to the Houthi militants.

“The first two deliveries will be mostly AK-74s, an upgraded version of the AK-47 assault rifle, and they discussed potentially selling the ‘Kornet’ anti-tank missiles and anti-aircraft weapons,” the sources claimed.

The impact of the Houthi–Russia relationship

Russia and Iran are deepening ties, using proxy groups like the Iran-backed Houthis to destabilize the global order and challenge Western influence. Their growing cooperation poses an escalating threat to international security.

As Western policymakers looked elsewhere, the Houthis quietly evolved into a strategic force empowered to execute operations with severe global consequences.

The illegal smuggling networks recruiting Yemenis to fight in Ukraine violate international law while offering Russia low-cost manpower in exchange for cash and political support. It’s a sign of how far Russia is willing to go, relying on irregular and unethical tactics, potentially influencing other actors to do the same.

Houthi attacks in the Red Sea threaten 15% of global trade. With Russian support, they gain access to advanced weapons and training, further undermining peace efforts in Yemen.

Things were “moving in the right direction,” said Swedish diplomat and UN Envoy for Yemen Hans Grundberg in 2023, after negotiations with the Houthis led to 887 detainees being released.

However, behind international negotiations in Geneva, Moscow and Tehran were transforming the Houthis “from mere terrorists into something more contemptible: traffickers in human misery, directly serving Russian military interests,” the Atlantic Council said.

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-605be766de04ba3d21b67fb76a76786a.jpg)

-2c683d1619a06f3b17d6ca7dd11ad5a1.jpg)

-661026077d315e894438b00c805411f4.jpg)