- Category

- Anti-Fake

Russia’s Only Hope for Real Change Lies in Losing the War in Ukraine

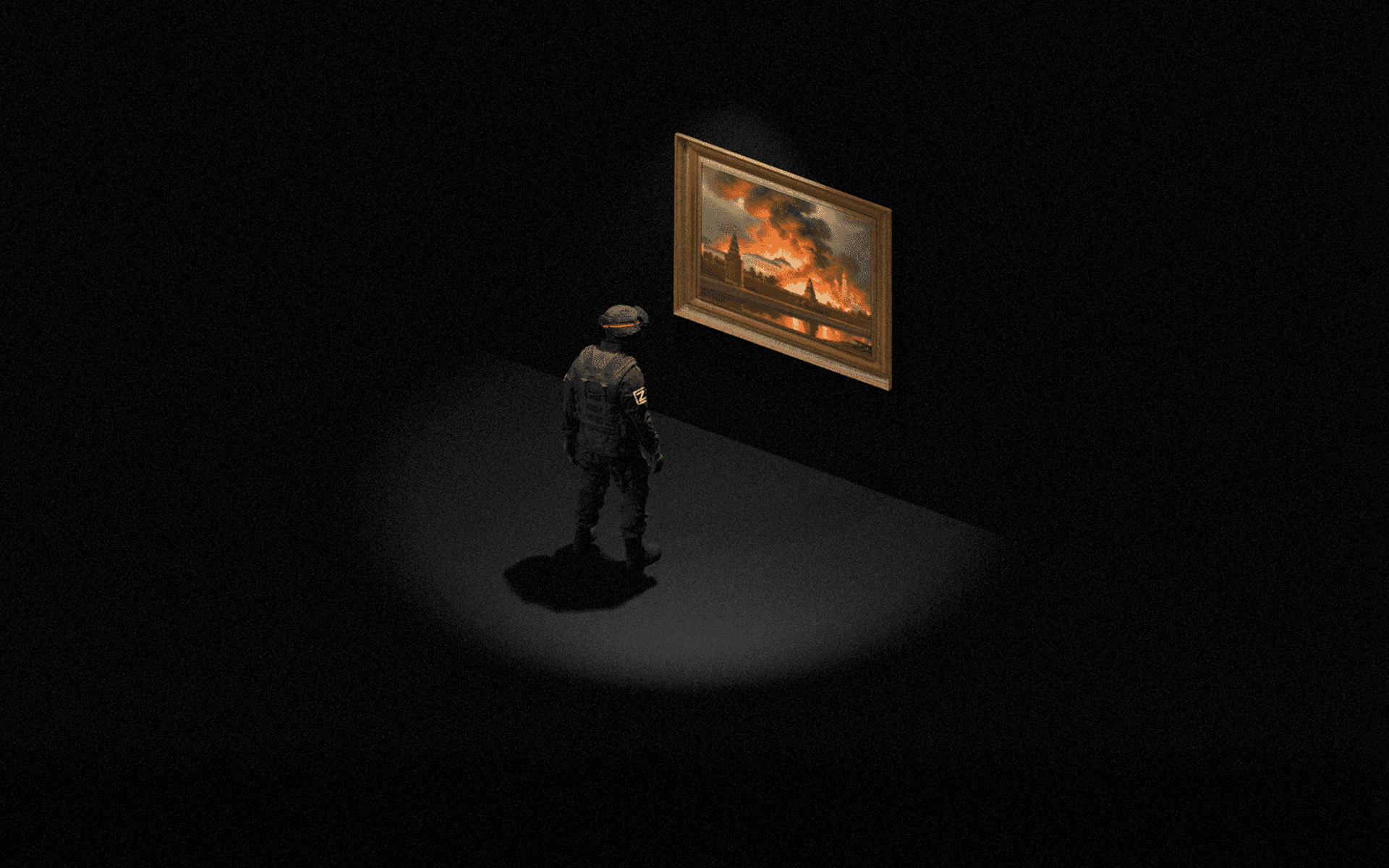

Nazi Germany confronted its crimes only after military defeat made denial untenable. Russia, by contrast, continues to equate victory with moral legitimacy. Without a clear and undeniable defeat, there is no sense of guilt—and without guilt, no basis for reflection or reform.

Nearly four years into Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian society shows little evidence of collective reflection or acknowledgment of responsibility. Kremlin propaganda is gaining ground in European and American cities; athletes who support the war are allowed to compete in international events; and Russian cultural figures supporting Putin are returning to global stages.

Peace talks without accountability

Thanks in part to the US efforts, discussions about possible peace negotiations continue to emerge. However, Russian officials consistently decline to participate in actual negotiations, rather than merely discussions about them—a fact recently acknowledged with concern by US Vice President J.D. Vance: “We remain committed to peace, but it takes two to tango. Unfortunately, what we have seen over the last couple of weeks is that the Russians refuse to sit down for any bilateral meetings with the Ukrainians. They refuse to sit down with any trilateral meetings where the President or some other member of the administration could sit down with the Russians and the Ukrainians at the negotiating table.”

Even amid discussions of potential negotiations, the issue of Russia’s responsibility for its aggression in Ukraine, including civilian casualties, widespread destruction, and alleged violations of international humanitarian law, is largely absent from the conversation.

💬 "Peace doesn't come when country which was invaded stops fighting. That's not peace. That's occupation," says Ukrainian Nobel laurate Oleksandra Matviichuk. pic.twitter.com/mSlrEpE6zw

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) August 31, 2025

Nor do Russians themselves appear to feel either personal or collective guilt for the war. Most support the invasion, while a significant and vocal portion expresses approval of civilian bombings and openly celebrates Ukrainian deaths. According to Russia’s own Levada Center, as of summer 2025, 74% of Russian citizens supported the war against Ukraine. The state continues to advance a narrative of a besieged nation under external threat—a framing that many citizens appear to accept. This narrative may serve to deflect feelings of guilt, an emotion often linked to processes of societal reflection and change.

“Guilt is a complex mix of emotions—sadness, anger, regret, anxiety, confusion, shame, remorse, self-awareness, and empathetic concern for others,” says crisis and military therapist Liubov Yunak. “Some experts see guilt as a duality, where fear and joy, sorrow and satisfaction coexist. It’s a complicated feeling that reflects social maturity.”

Perhaps the only attempt by Russians to recognize collective guilt was Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin’s regime between 1953 and 1964. But even that was superficial and selective. Khrushchev’s denunciation did not fully acknowledge the broad collective responsibility of the Soviet system or the Soviet people; many historians argue he tried to place the blame primarily on Stalin personally, rather than acknowledging structural or societal complicity. Khrushchev himself, as historian Yaroslav Hrytsak points out, “had blood up to his elbows.”

“Even that timid effort kept Stalin from being rehabilitated for quite a while,” says Hrytsak. “That all changed under Putin. Stalin is being hailed as a hero again, and monuments to him are resurfacing. Russia’s rapid pivot from anti-Stalinism to Stalinism shows just how shallow its reckoning with past crimes really was. If Russia ever becomes a democracy again, it will face a monumental task in confronting its own history.”

So far, there are no real signs that such a reckoning is even beginning. As long as a person—or a nation—has not experienced defeat, the illusion of moral rightness remains intact. For Russians today, that illusion takes the form of a persistent narrative that by invading a neighboring country, “we defend our country”—a message regularly echoed by Russian officials and by Putin himself. A clear defeat would dismantle this framework of self-deception. That is why any broader awakening is unlikely to occur until military failure becomes both undeniable and irreversible.

Still, could a moral shock over their country’s crimes awaken a sense of guilt?

Why Russia can’t reform without defeat

Even proven atrocities by Russian soldiers in Bucha, Mariupol, and other Ukrainian cities haven’t triggered mass reflection or guilt. Simply admitting the truth would mean accepting responsibility, says Yunak.

“The average Russian’s psychological makeup, lacking any reflection, builds a kind of collective moral deafness—it’s the only way to ‘survive,’” she explains. “They retreat into clichés like ‘not everything is so clear-cut,’ or use primitive denial mechanisms like: ‘Bucha was staged!’”

Russian propaganda supports this mindset. The “firehose of falsehood” strategy floods all media channels with multiple, contradictory versions of events, disregarding truth and consistency—just enough to muddy the waters.

But the human psyche itself has powerful mechanisms for avoiding responsibility. Yunak offers an analogy to explain how the brain reacts when confronted with news that should evoke deep guilt. In cases where a father sexually abuses his own daughter, the daughter, not the father, may be the one cast out of the family. If the truth were acknowledged, those around her could experience intense guilt for not having protected her. “People cling to denial—because it is hard for the psyche to bear that level of responsibility,” says Yunak.

In Yunak’s view, similar psychological patterns help explain how many Russians respond to the war. While there are no strict boundaries, she observes a few recurring tendencies. Some people remain largely uninformed and susceptible to manipulation—sometimes because of limited access to independent information. Yet many others actively avoid uncomfortable truths, relying on denial, repression, or emotional detachment. And then there are those who engage more intellectually, but use rationalization to justify the war, framing it in false ideological terms such as “we’re fighting Nazis” or “we’re defending ourselves from the West.”

Only the latter two groups—those who are avoiding or rationalizing—may eventually be capable of experiencing guilt, says Yunak. However, as long as Ukrainian territories remain under the Russian occupation, even preliminary investigations into war crimes are impossible. United Nations reports that an “climate of fear” prevails in the Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories. Some 600,000 Ukrainian children are being educated in schools where their native language is banned, and military training is mandatory.

Moreover, the Russians have been unlawfully deported or forcibly transferred nearly 20,000 of Ukrainian children. In March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Russian leader Vladimir Putin and the Commissioner for Children’s Rights Maria Lvova-Belova, specifically for the abduction of Ukrainian children to Russia. Yet these crimes are ongoing.

History, however, has shown that even the most harrowing atrocities can, in time, lead to collective remorse.

The German post-war model

After 1945, following Germany’s defeat in World War II, denial was no longer a viable option. The world saw the truth about Nazi atrocities and the Holocaust, leaving no room for “it’s not so black and white.” Defeat ended the war, but also forced the nation to confront collective trauma. Though even that was a difficult and gradual process.

“What proved pivotal was Karl Jaspers’ essay on historical responsibility?” says Hrytsak. “Germans at the time were pretending nothing had happened—claiming they hadn’t known about the camps or the Holocaust. But Jaspers said no, the Germans were guilty. There is such a thing as collective moral guilt. That’s what Russians lack—a Jaspers-like figure.”

Even Russian opposition figures routinely reject the idea of national responsibility, insisting that only individuals can be guilty. That means it’s not Russians who are at fault—it’s Putin. Maybe a few generals and bureaucrats, too. The rest, supposedly, were just “following orders”—as Nazi officer Adolf Eichmann claimed at his post-war trial. Yet Eichmann was one of the Holocaust’s chief architects.

It took Germany just over a generation to begin confronting its guilt. Hrytsak notes that by the 1960s, young Germans were asking their parents and grandparents what they did during Hitler’s reign.

“To collectively accept responsibility is to risk the collapse of a nation’s identity,” says Yunak. “It’s easier to blame past generations than to see yourself as guilty. In postwar Germany, we saw this dynamic clearly. Early on, most Germans saw themselves as victims—persecuted, not perpetrators. They viewed Nazism as something that happened to them, not something they actively did.”

She points out that the first postwar generation lived with fear, stigma, and silence. The second experienced anxiety and self-reproach. Later generations built memorials and cultivated a culture of remembrance.

Eventually, war crime education, historical reflection, and memorialization became integral to the formation of a new German identity. Germany didn’t change overnight—but defeat made change possible.

How life in Russia changed during the war

Russia still seems to live in a mirror reality—where victory equals righteousness, and strength equals morality. The cult of military glory has replaced critical thinking; hero-worship of the past has destroyed the capacity to see the present.

Today’s Russian propaganda follows the same pattern: bombings and human-wave assaults are framed as “liberation,” enemies are “Nazis,” and the world is a “conspirator.” Until an undeniable collapse comes, there’s no incentive for society to rethink anything.

A truce without accountability is just a pause before the next war. Any compromise that lets Russia cling to the illusion that it hasn’t lost will only delay the inevitable—without preventing it.

Russia’s defeat is not about punishment—it’s about possibility. A chance for a society long hidden behind imperial pride to finally confront the reality of its actions. Only then can there be trials, open archives, education about crimes, and a culture of remembrance. Without this, there will be no “other Russia.”

-29ed98e0f248ee005bb84bfbf7f30adf.jpg)

Germany’s story shows that painful reckoning is the only path to renewal.

“Putin is obsessed with Ukraine in a similar way Hitler was obsessed with Jews,” says Hrytsak. “Once he’s gone, the war may stop—or enter a stagnant phase. Someone from his inner circle will likely take over, like Khrushchev after Stalin, and say: ‘It wasn’t us—it was him. He fought a senseless war. Let’s make peace and lift the sanctions.’”

We already know what that leads to. Germany’s failure to reckon with its guilt after World War I led to the worst war in history.

Ukraine’s victory is not just a matter of justice or European security. It’s a chance to spark a reckoning in Russia.

And perhaps the only way to prevent the next war.

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)

-4d7e1a09104a941b31a4d276db398e16.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-3db1bc74567c5c9e68bb9e41adba3ca6.png)