- Category

- Business

Are Global Brands Going Underground? How Business Is Adapting to Russian Airstrikes in Ukraine

When the full-scale war began, businesses left Russia due to sanctions, while their departures across Ukraine were driven by the threat of Russian missile strikes. Now, big brands are coming back to Ukraine. Here’s how global companies are learning to operate under air-raid alerts—and sometimes, underground.

The golden arches that still stand

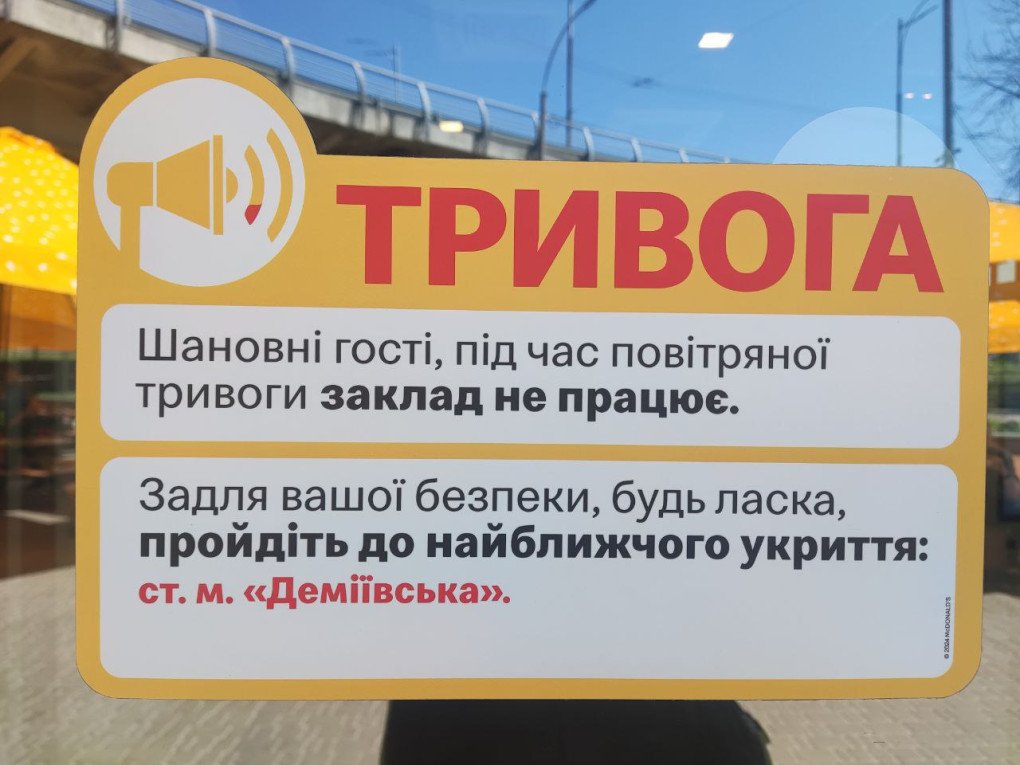

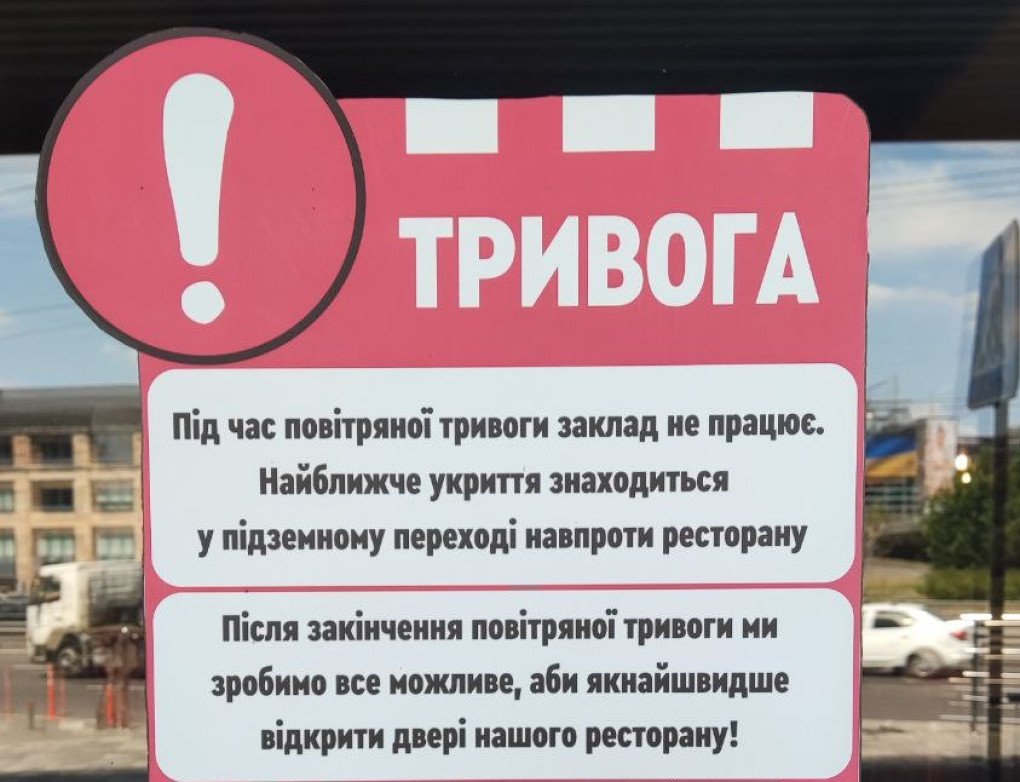

It was the middle of the day in Kyiv, and the McDonald’s attendant announced that orders had stopped, while a colleague calmly ushered customers outside. An air raid alert had just sounded, and staff were strictly following safety protocols. I filed out with everyone else in what had become a now-familiar scene in wartime Ukraine.

Even in the capital—where the time between sirens and impact is longer than in frontline regions—clearing the dining area, stopping service, and evacuating staff is no small feat. These repeated drills have become a routine, and McDonald’s crew members huddling on makeshift stools in underpasses or on metro platforms have become a familiar part of the city’s landscape.

Several months after suspending business at the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion, McDonald’s resumed operations in Ukraine in late 2022—a move widely seen as a symbol of resilience. And with as many as 400 employees currently serving in the Ukrainian Armed Forces, it is a stark reminder of life in a nation at war.

New locations have opened since returning, bringing the total to more than 100 nationwide. In sharp contrast, McDonald's announced in May 2022 it would exit Russia, calling continued ownership “no longer tenable” amid the war in Ukraine—“nor is it consistent with McDonald’s values.” It sold the business, removed the brand name and logos from the restaurants—a move the company described as “de-Arching”—writing off $1.3 billion in the process.

From counters to couriers, Kyiv keeps delivering

Other major US food brands in Ukraine follow similar rules, pausing service during air-raid alerts and relocating staff and customers to shelters. Among them, KFC exited Russia in April 2023, while Cinnabon said in March 2022 it would suspend new investment and development there. In Kyiv, all seven Cinnabon outlets are located in shopping centers that, during alerts, follow mall protocols: closing trading floors and directing staff and visitors to parking-level shelters which we will explore in a later chapter.

Domino’s, which left Russia after filing for bankruptcy in August 2023, operates differently as an off-premise-first pizza brand. While other restaurants in Kyiv suspend deliveries during air-raid alerts, Domino’s keeps orders moving—a small act of continuity in a city under fire—though it raises obvious safety questions.

Meanwhile, Glovo, a global on-demand platform, states that it suspends service in Ukraine during alerts and advises couriers to take shelter. “We monitor the cities we operate in, make sure they’re safe and keep them open; and if a city is in trouble [air-raid alerts—ed.], we close the services,” co-founder Sacha Michaud said in a June 2024 interview. In practice, however, the app does not always fully shut down.

The city that sleeps underground

Hotels have had to adapt in unique ways to the realities of war. Unlike fast-food chains—where customers must leave and seek shelter elsewhere during an air raid—overnight guests can’t simply be turned out onto the streets. This is especially true in the middle of the night, when Russian attacks are most frequent. Many international chains have transformed their facilities to handle various scenarios, including converting underground parking areas into on-site safe areas for those on the premises.

The Radisson Blu Hotel, Kyiv City Centre, is a five-minute walk from the Golden Gate metro station, which is classified as a civil-defense structure and can serve as a bomb shelter. For guests’ convenience, the hotel has also converted its own level-2 parking into a safe zone to ride out the sirens: around 20 beds, plenty of beanbags, and enough tables and chairs for everyone.

“Some guests even bring their own yoga mats,” general manager Juris Zudovs tells us. “It’s an emergency situation. We can’t make it as comfortable as a guest room, but it's a place to wait out the alert. Sometimes it lasts a few hours; sometimes, unfortunately, the whole night.”

Guests are advised at check-in to download the official air-raid app, while the hotel’s PA, linked to Kyiv alerts, sends announcements to all rooms and public areas at any hour. Referring to a Russian attack in late August, which killed 25 civilians in Kyiv, Zudovs notes: “While some guests don’t react immediately, when there are really heavy blasts outside, a lot of people go down to the parking level.”

Beds on level-2 are “first come, first served,” he adds. “If an alert starts early enough, some guests choose to bunk down there for the night, regardless of whether the alert has ended.” The level also includes conference rooms, so meetings can continue uninterrupted during daytime warnings; it’s not unheard of for morning delegates to pass sleeping guests on their way to a 9 a.m. session.

As Russia’s full-scale invasion began—and with temperatures near freezing—Radisson Blu opened its doors to shelter displaced residents in its secure basement level. In the weeks that followed, staff partnered with a local supermarket to prepare and distribute hundreds of free meals daily to those in need. Radisson Hotel Group suspended new partnerships and investments in Russia on March 18, 2022.

The show must go on, but first the sirens must go quiet

Cultural life in Kyiv has adapted to wartime conditions, with cinemas, theatres, and concert halls operating under the constant threat of interruption. Air-raid alerts dictate when shows pause, resume, or are abandoned altogether.

In January 2025, the audience for The Snow Queen at Kyiv’s National Opera was limited to 560, less than half the hall’s 1,300 seats. The restriction mirrors the capacity of the opera house’s shelter, the number of people who could be protected if sirens forced a pause mid-performance. Reflecting on the audience’s experience, prima ballerina Tetiana Lezova told The Times: “Each performance can be the last.”

Cellist Vladyslav Primakov of the Kyiv Philharmonic recalled in The Guardian how a concert might suddenly be interrupted by air-raid alerts. “You have to stop, take cover for an hour, then get back on stage and re-establish your rapport with the audience”—something he describes as exhausting. If an alert extends beyond that hour, the Philharmonic postpones the performance and announces a new date.

Disruptions extend beyond live performances. Major cinema chains in Kyiv, including Multiplex, suspend screenings when air-raid sirens sound and evacuate guests to designated shelters. Depending on the venue, showings resume if the alert lasts 15 to 30 minutes; longer delays lead to cancellations. In such cases, Multiplex CEO Roman Romanchuk said, viewers can choose vouchers for another show or a refund. “What matters most to us is that viewers come back, even on a second or third try, to finish their favorite film,” he said.

Business as usual, almost

Malls

Retail in Ukraine has adapted to wartime routine, as shopping centers and supermarkets work around air-raid alerts. After the late-June 2022 Russian strike on Kremenchuk’s Amstor Mall that killed 21 people, sites nationwide adopted protocols to close trading floors during alerts and route people to shelter—though, as lawyer Yevhen Bulimenko notes, current law “does not impose a direct obligation” to suspend operations, so businesses set their own plans.

Across Kyiv, malls close during alerts and direct shoppers and staff to shelter—usually in on-site underground parking or the nearest metro—until the all-clear; reopening times have significantly decreased to five minutes, where previously it took half an hour, says commercial director Natalia Kravets.

Among mall tenants juggling business and bunker are global fashion brands H&M and Inditex—which includes Zara; both paused operations in Ukraine at the outset of Russia’s full-scale invasion. H&M, which operated eight Ukrainian stores, resumed trading in November 2023, saying “the safety of colleagues and customers will always be the first and foremost priority.” Zara, with more than 80 stores, resumed trading in April 2024, adopting a similar safety-first stance.

Each company exited the Russian market in response to its illegal invasion, with the Swedish retailer H&M saying in July 2022 it was “impossible … to continue business in Russia.” Discussing a possible return to the Russian market, Spain’s Inditex CEO Óscar Maceiras said in June 2025 that the conditions were “certainly not” in place. However, subsequent reporting states that the retailer Tvoe is operating in seven Russian cities, reportedly selling Inditex brands including Zara, Bershka, and Stradivarius.

Supermarkets

In the early months of Russia’s full-scale war, supermarkets across Ukraine routinely shut trading floors during air-raid alerts—even in relatively safe western regions like Zakarpattia, where I was living. Today, some stores still close on sirens, but many national chains stay open.

On a recent visit to Auchan in a Kyiv mall, I had just finished asking the manager about their shutdown protocols when he showed me a notification on his phone, incredulous. A fresh air-raid alert had just appeared, and he gestured for me to watch as shoppers kept strolling in. While other stores in the chain paused trade, this supermarket did not, owing to its location on the mall’s lower-ground level (minus one), effectively functioning as a shelter, he explained.

French retail giant Auchan halted operations in Ukraine in the early weeks of the full-scale invasion amid disrupted supply chains and escalating safety threats, then began a gradual reopening in late 2022 as conditions stabilized. In Russia, the company remains open for business: “We are continuing to work for the good of the country’s population,” Auchan said in a January 2025 statement.

Home-improvement hypermarkets

Home-improvement chains remain fixtures in the Ukrainian marketplace as the country rebuilds what Russia has destroyed, with government housing compensation now reaching 143,000 families and totaling close to $1.2 billion. Domestic giant Epicenter—whose Kharkiv hypermarket was hit by two Russian guided bombs in May 2024, killing 19 people—saw sales grow through the war, evidence of steady demand for repair and reconstruction materials.

Danish homeware chain JYSK was among the first international retailers to resume business in Ukraine within weeks of Russia’s full-scale invasion. At the same time, the company permanently closed all 13 stores in Russia, permanently exiting the market. In May 2023, JYSK rebuilt and reopened its store in Odesa’s Riviera Shopping Center, which had been previously damaged by a Russian missile strike. In late 2024, JYSK marked its 20th anniversary in Ukraine and the opening of its 100th store in the country.

IKEA, now fully exited from the Russian market, closed its Kyiv store in 2022 and still stands empty, both as a pause and a promise. Mall operators floated a 2025 reopening, but the company says any return depends on staff and customer safety, noting, “we cannot say when this will happen.” If McDonald’s return in 2022 embodied resilience, an IKEA reopening would be a symbol of continued optimism for retailers, investors, and households nationwide.

From fast-food counters to hotel basements and mall parking areas, global brands in Ukraine have learned to endure on every level—including underground. UKRSIBBANK, part of the French BNP Paribas Group, told UNITED24 Media that its Sumy team continues to serve clients from the branch’s shelter during air-raid alerts. The message is simple: whether the all-clear has sounded or not, Ukraine is open for business.

-7f54d6f9a1e9b10de9b3e7ee663a18d9.png)

-270e13af43760897c8cb3e7f3ee9adf1.png)

-b63fc610dd4af1b737643522d6baf184.jpg)

-099180a164f53abb1128c9b5025a2b0e.jpg)

-46f6afa2f66d31ff3df8ea1a8f5524ec.jpg)

-4390b3efd5ecfe59eeed3643ea284dd2.png)