- Category

- Latest news

What It Costs Russia to Bomb Ukraine? From Iskander to Kinzhal

Russia’s long-range strike arsenal—its Kalibrs, Iskanders, Kinzhals, and Zircons—has come to define the war it wages against Ukraine. But for the first time, leaked procurement records obtained and analyzed by the Ukrainian defense outlet Militarnyi shed light on what these weapons really cost—and how many are still being built.

The documents reveal exact unit prices, production timelines, and volumes for almost every missile in the Russian arsenal, exposing both the economic strain and the continuing scale of Moscow’s strike capacity, according to the documents obtained by Militarnyi on October 24.

The trove represents the first documentary confirmation of Russia’s missile pipeline through 2027, offering rare visibility into a sector that Moscow treats as one of its deepest secrets.

The price hierarchy of destruction

Russia’s new records read like an accountant’s view of modern warfare. The 9M727/9M728 cruise missiles, both derivatives of the Iskander system, are contracted at roughly $1.6 to $1.7 million apiece.

Their cousin, the 9M729—whose extended range triggered the end of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty—costs about $1.8 million each.

The naval Kalibr series, one of the most widely used weapons in Russia’s arsenal, costs around $2 million per unit.

Failed launch of a Kalibr cruise missile from an

— ToughSF (@ToughSf) January 8, 2025

Udaloy-class russian frigate:https://t.co/BZvcAhqcm3 pic.twitter.com/1E42A5C2El

Air-launched systems are pricier still. The Kh-101 strategic cruise missile averages between $2.0 and $2.4 million, while its next-generation derivative, the Kh-BD (“Item 506”), jumps to $4.2 million.

Among ballistic systems, the Iskander-M’s various configurations range between $2.3 and $3 million, and the air-launched Kinzhal, adapted from the same base technology, costs $4.5 million.

At the very top of the hierarchy stands the Zircon—one of Russia’s hypersonic missiles, valued between $5.0 and $5.6 million per round.

Together, these prices paint a picture of a country investing billions in the steady renewal of its long-range missile stockpile, even as sanctions squeeze its broader economy.

The cruise missile triad

9M727 and 9M728—the Iskander family

The workhorses of Russia’s land-based cruise arsenal, the 9M727 and 9M728 missiles, are used for precision strikes when drones lack the range or punch to destroy hardened targets.

Each carries a 480-kilogram warhead and can fly roughly 500 kilometers.

According to Militarnyi, OKB Novator—the Yekaterinburg-based missile design bureau—received at least two contracts covering 303 missiles for 2024–2025, each priced between 135 and 142 million rubles ($1.6–1.7 million).

-3336ca785df0ebe3e84fa8baef71d263.jpg)

9M729—the INF treaty breaker

The upgraded 9M729, infamous for its role in the 2019 collapse of the INF Treaty , stretches its reach beyond 2,000 kilometers.

It is incompatible with standard Iskander launchers, requiring the specialized “Iskander-M1” platform. Russia’s defense ministry ordered 95 units for 2025 at roughly $1.8 million each, Militarnyi reports.

Rare footage of Russian Iskander ballistic missile launch from close point. pic.twitter.com/78w9uFpqMW

— Clash Report (@clashreport) August 19, 2024

3M14 “Kalibr”—the sea-launched staple

According to Militarnyi, the Kalibr family—fired from frigates, corvettes, and submarines—has been Russia’s weapon of choice for deep strikes on Ukrainian infrastructure.

Procurement papers show two major contracts: 240 missiles for 2022–2024 and another 450 for 2025–2026. Each costs about 168 million rubles, or just over $2 million.

In addition, a smaller batch of 56 “3M-14S” versions with nuclear warheads is scheduled for production between 2024 and 2026, each priced up to $2.3 million.

🚨 The Kalibr missile has been launched from the Black Sea. pic.twitter.com/zq4noJwqEM

— Defence Index (@Defence_Index) June 5, 2025

Militarnyi notes that Novator is responsible for manufacturing the Kalibr line, whose range varies from 1,500 to 2,600 kilometers depending on configuration.

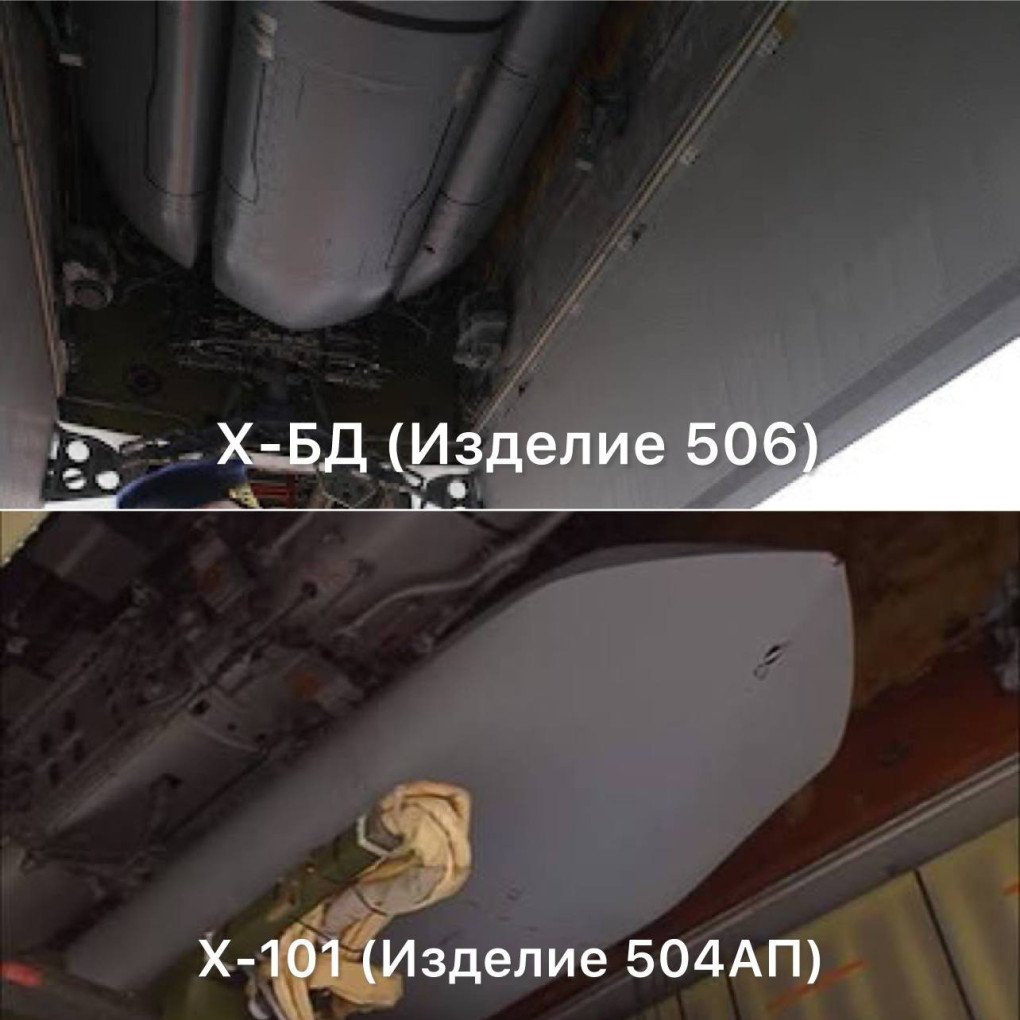

Kh-101 “Item 504AP”—Russia’s air-launched striker

The Kh-101 has become one of the most frequent missiles seen over Ukraine’s skies. Designed for strategic bombers like the Tu-95MSM and Tu-160, it uses a turbofan engine and an advanced guidance system that combines satellite, inertial, and terrain-matching navigation.

Militarnyi’s records show that Russia’s MKB Raduga design bureau received contracts for 525 missiles in 2024 at $1.97 million each, 700 more in 2025 at up to $2.3 million, and an additional 30 units in 2026.

The latest “504AP” version incorporates countermeasure dispensers and electronic warfare equipment to protect against infrared-guided interceptors, giving it a range of about 2,500 kilometers and a top-tier role in Russia’s long-range strike campaign.

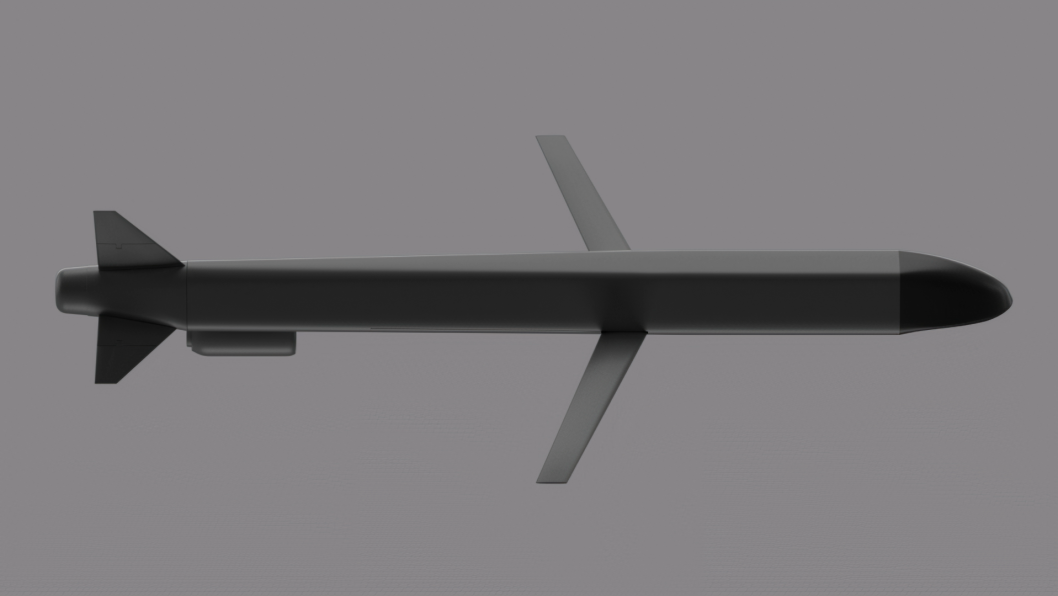

Kh-BD “Item 506”—the next step

If the Kh-101 is Russia’s proven long-range cruise missile, the Kh-BD is its ambitious successor. Dubbed “Item 506,” this new design is roughly three meters longer, carries an 800-kilogram warhead, and can reportedly reach up to 6,500 kilometers.

According to Militarnyi, Raduga received two orders—one for 2024 and another for 2026—for a total of 32 missiles, both conventional and nuclear. Each costs about 337 million rubles, or $4.2 million.

The Kh-BD is expected to arm the future PAK-DA stealth bomber and be integrated into the upgraded Tu-160M aircraft. Its development aims to restore the range lost in the Kh-101 after engineers added a tandem warhead that reduced fuel capacity.

The ballistic backbone

9M723 “Iskander-M”

For strikes against military targets, Russia relies on its 9M723 Iskander-M tactical ballistic missile—a design that remains difficult to intercept due to its quasi-ballistic flight path. The missile can carry a half-ton warhead, either high-explosive, cluster, or specialized, Ukrainian defense media outlet Defense Express noted.

Kolomna’s Machine-Building Design Bureau (KBM) received contracts for 1,202 Iskander-M missiles for 2024–2025.

Ukrainians discovered a Russian missile that fell into the Dnieper River during the Russian missile strike on 2 January of 2024.

— 𝔗𝔥𝔢 𝕯𝔢𝔞𝔡 𝕯𝔦𝔰𝔱𝔯𝔦𝔠𝔱△ 🇬🇪🇺🇦🇺🇲🇬🇷 (@TheDeadDistrict) January 26, 2024

The missile is 9M723 of Iskander-M. pic.twitter.com/8JuyenrSgD

Militarnyi’s analysis of the documents reveals a breakdown of variants: the 9M723-1K5 cluster model (185 units at $2.86 million each), 9M723-1F1 with a penetrator warhead (59 units at $2.86 million), 9M723-1F2 high-explosive (771 units at $2.3 million), and 9M723-1F3 improved version (217 units at $2.3–2.9 million).

A smaller order of 18 units labeled 9M723-2—possibly the long-rumored “Iskander-1000” with extended range—is planned for 2025, each costing about $2.6 million.

According to Militarnyi, these numbers show that Russia plans to produce more than 1,200 Iskander-class ballistic missiles within just two years—a remarkable figure that underscores the priority given to this weapon despite Western sanctions.

Kinzhal—the “hypersonic” derivative

The air-launched Kinzhal (9-S-7760) is essentially an Iskander adapted for flight from MiG-31K and MiG-31I interceptors, Militarnyi reports.

It launches at around 25 kilometers altitude and accelerates to over Mach 5.5, briefly reaching Mach 10 in its ballistic arc before slowing to about Mach 3 on descent—the stage when Ukrainian Patriot batteries have proven capable of shooting it down.

Each missile costs roughly $4.4 million. Contracts seen by Militarnyi show 44 units ordered in 2024 and 144 in 2025.

The launch of the Kinzhal hypersonic cruise missile as part of a planned exercise of the strategic deterrence forces conducted under the leadership of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation V.Putin #DefenceMinistry #ArmyRussia #Exercise pic.twitter.com/vovVU3M0h6

— Минобороны России (@mod_russia) February 19, 2022

The Kinzhal carries a 480-kilogram penetrating warhead packed with about 150 kilograms of high explosive and can also mount a nuclear payload.

Technically, the missile uses a dual-mode solid rocket motor similar to that of the Iskander but optimized for high-altitude ignition.

Its guidance suite combines inertial and satellite navigation with an active radar seeker derived from the 9B918 model, giving it terminal accuracy measured in tens of meters.

-8ff74eb427048fb43a21b623ab814c0b.png)

Zircon—the myth and the metal

Few Russian weapons have been surrounded by more hype than the 3M22 Zircon. Presented by state media as a scramjet-powered “hypersonic” missile capable of outpacing all Western defenses, it has been used sparingly and, according to Ukrainian investigators, with poor accuracy, Militarnyi stated.

Militarnyi’s procurement documents list Zircon at 420–450 million rubles per missile ($5.0–5.6 million), with deliveries of 80 units per year between 2024 and 2026. It can be launched from both naval platforms and land-based Bastion systems.

Debris from a downed missile over Kyiv offered the first physical proof of its real design. Photos showed a 400-millimeter-diameter warhead casing weighing around 150–200 kilograms, with just 40–80 kilograms of explosive.

Analysts detected the smell of Decilin-M, a high-energy liquid fuel used in experimental ramjets—confirming that the weapon runs on a liquid-fuel air-breathing engine rather than a solid booster alone.

Its fuselage, built largely from titanium and composite materials, uses thin walls and a “soft” outer layer likely serving as a thermal interface for heat insulation. The design features a ring-shaped air intake hidden under a detachable cap at launch—similar to the older 3M55 Oniks.

According to Militarnyi, this evidence suggests Zircon is not a new technological breakthrough but a heavily modified Oniks with a lighter structure, reduced warhead, and higher speed. The missile’s range is estimated between 600 and 1,000 kilometers—short of Russia’s initial boasts.

I don’t usually post MOD videos but this one shows the launch of Zircon Hypersonic missile from the Admiral Golovko during Zapad 2025. pic.twitter.com/yJ2ruo1U8S

— ayden (@squatsons) September 14, 2025

On the same day that fragments were recovered, Patriot PAC-3 interceptors shot down several Zircons approaching Kyiv.

Militarnyi’s sources say the missiles slowed to around Mach 3 on their terminal approach, making interception possible once the plasma sheath dissipated. The finding undercuts Moscow’s claim that Zircon is “impossible to shoot down.”

The industry behind the arsenal

Militarnyi’s investigation doesn’t just expose numbers—it outlines an industrial network that remains adaptive and productive despite sanctions.

Novator, Raduga, and KBM—the three core bureaus responsible for Russia’s major missile families—continue to receive multi-year orders. Currency fluctuations account for small price variations in the documents, but the overall pattern shows no pause in procurement.

Novator, founded in 1947 and absorbed into the Almaz-Antey defense conglomerate in 2002, remains the central producer of naval and ground-launched cruise missiles.

Raduga, specializing in air-launched weapons, handles both the Kh-101 and Kh-BD projects.

KBM in Kolomna maintains the Iskander and Kinzhal lines, the backbone of Russia’s tactical and quasi-hypersonic force.

Even at conservative estimates, Russia’s 2024–2027 missile spending exceeds several billion dollars—an enormous burden for a wartime economy already strained by mobilization and sanctions. Yet the documents confirm that contracts remain active, payments scheduled, and deliveries planned through at least 2027.

What the numbers reveal

The data points to a two-track strategy: sustain mass production of proven systems like the Iskander, Kalibr, and Kh-101 while pursuing expensive prestige projects such as the Kh-BD and Zircon.

The cost gradient—from $1.6 million for basic cruise missiles to over $5 million for advanced prototypes—reflects both industrial capability and propaganda priorities.

According to Militarnyi, Russia’s missile industry is compensating for Western sanctions by sourcing components domestically where possible and stockpiling imported electronics through parallel trade networks.

The consistency of the procurement schedule suggests that Moscow expects to maintain large-scale strikes for years, not months.

For Ukraine and its partners, the takeaway is straightforward: Russia’s deep-strike capacity, though not infinite, remains substantial. The leaked contracts quantify what has long been assumed—the Kremlin is still investing heavily in the tools of long-range terror, and those tools continue to roll off production lines.

The cost of the range

The documents obtained by Militarnyi offer a granular look at how Russia balances cost, technology, and propaganda. For each dollar added in missile sophistication, the returns in accuracy or reliability are questionable.

Yet the political symbolism of “hypersonic” and “nuclear-capable” designations ensures that projects like Zircon and Kh-BD receive disproportionate funding.

The intact warhead of the downed Kh-101 cruise missile (9-E-2648) pic.twitter.com/JJcJXab6pJ

— PS01 □ (@PStyle0ne1) March 21, 2024

Meanwhile, cheaper systems—Iskander, Kalibr, and Kh-101—do the actual work of sustaining Russia’s campaign against Ukrainian cities. In that sense, the missile budgets are less about battlefield necessity and more about maintaining the illusion of technological supremacy.

Earlier, Russia’s United Aircraft Corporation (UAC) had breathed new life into its Cold War-era aircraft by arming the MiG-31 interceptor with the long-range KS-172 missile.

-331a1b401e9a9c0419b8a2db83317979.png)

-c439b7bd9030ecf9d5a4287dc361ba31.jpg)