- Category

- Life in Ukraine

These Kids Lost Everything to Russia’s War. Now a Ukrainian Camp Is Helping Them Heal

“I drew death and war. And the future—because I’m scared of what’s coming.” Seventeen-year-old Valeriia lived through the Russian occupation and lost her father. Now she’s one of hundreds of children finding a way forward at Gen.Camp, where games and therapy help war-traumatized kids begin to heal.

Tens of thousands of Ukrainian children have lost their parents because of Russia’s aggression. Gen.Ukrainian, the organization behind Gen.Camp, was created for children who have experienced traumatic events—lost loved ones, endured captivity, were forcibly deported, or lived under Russian occupation. Each year, Gen.Ukrainian runs a handful of these camps, offering what looks like a joyful summer retreat. But beneath the hikes, movie nights, and dance parties lies something far more urgent: a trauma-focused recovery program designed to help kids live with their grief—and move forward.

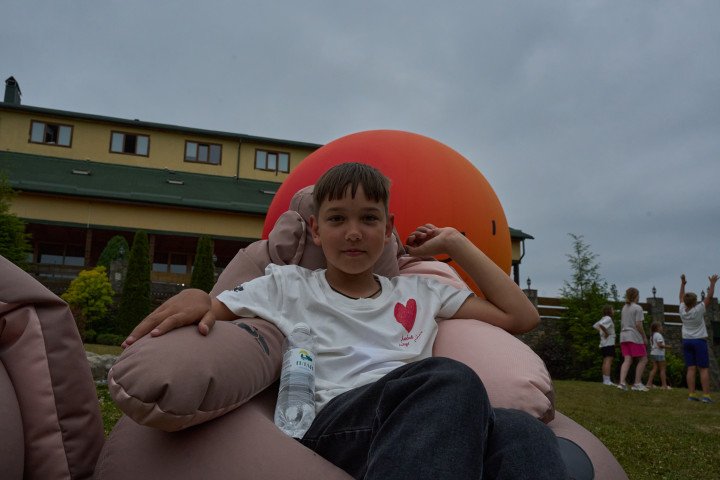

“My dad was a combat medic,” says 9-year-old Ivanka, whose father died in December 2023. “When he left for the front, I gave him a piece of gum. When they brought his body back, that same gum was in his things. He kept it. It was so strange to see it again.”

Ivanka’s father loved to sing and play guitar. She turned nine during her time at camp, and now carries a small orange ukulele wherever she goes—a guitar is still too big for her.

“I’ve almost gotten used to the fact that my dad is gone,” she says. “Before, I’d cry every time I talked about him. I still love him a lot, but I don’t cry as much now. I dream he’ll come back to life, even though everyone says that’s impossible. I also wish the war would end. There was World War I, World War II… now it feels like World War III. It’s so weird.”

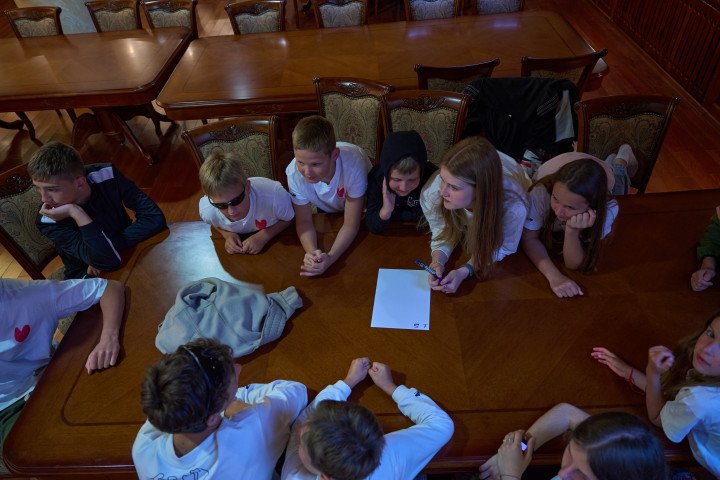

Ivanka is one of 50 children attending the 11th Gen.Camp, nestled in Ukraine’s Carpathian Mountains. For a few weeks, kids between 7 and 17 swim, hike, play, and bond—learning how to live with their grief. Every child here has lost someone because of Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Reclaiming the value of life

Life at Gen.Camp follows a schedule: wake-up at 8 a.m., three meals a day, two snack breaks, plus lectures, board games, swimming, sports, dancing, outdoor movie nights, mountain hikes, and more. Phones are allowed for just one hour a day. Each child also receives individual and group therapy sessions.

“We work with the highest concentration of grief you can imagine,” says Vanui Martirosyan, lead psychologist at Gen.Ukrainian. “Our job is to help these kids cope with it, find hope, and a path forward.”

“The highest concentration of grief” is no exaggeration.

A boy runs past whose mother was raped and murdered by Russian soldiers in the room next to his. Another camper, nine-year-old Misha, was running to his parents during an air raid when a Russian missile hit the children’s room—his brother and sister were killed. He’s back at camp for the second time.

Twelve-year-old Arina survived a Russian drone strike. A Shahed hit her apartment. She dug through the rubble with her bare hands to reach her father and brother. Her brother didn’t survive.

Ten-year-old Artem lost his father, a commander in an anti-tank missile unit, to a landmine. Afterward, he grew close to his uncle. Then the uncle went to the frontlines—and never came back.

“He died too,” Artem says simply.

Artem dreams of becoming a pilot.

“I really love planes,” he says. “Especially the An-225 Mriia—the biggest plane in the world.”

To show how massive it was, he reaches for a comparison he understands now.

“The Mriia could carry about 20 Leopard tanks in one go,” says Artem

The iconic aircraft An-225, a symbol of Ukrainian pride, was destroyed by Russian forces in the early days of the invasion.

Artem also likes the F-16. “They’re good planes, long-range,” he says seriously.

Artem doesn’t want to fly just to fly—he wants to be a military pilot. Many of the kids here talk about joining the army. When you’ve lost a father, a mother, a brother, it’s easy to feel like there’s only one understandable path.

“Some of them think about revenge,” says Martirosyan. “They want to find the person who killed their loved one. We don’t tell them not to be angry. We tell them: hate is normal. You have a right to it. But we try to bring them back to valuing their own lives. We try to turn that anger into strength, not destruction.”

Most of these children never had a chance to learn how to grieve. Someone they love was there—and then wasn’t. How does one process that? How does one mourn? Move on? Gen.Camp tries to teach exactly that.

Healing through games

A girl lies on the grass, looking up at the sky. A group of kids stretches a transparent mesh above her, toss colorful balls onto it, and walk around in a circle. The balls bounce up and down, never falling on her. She smiles.

It’s one of Gen.Camp`s exercises. The balls represent the fears the girl named earlier. Their bouncing — close but not touching—symbolizes that fears can be managed.

In another exercise, children hang bells—one for each fear—creating a “corridor” they must walk through without touching a single bell.

“It’s a game to reinforce caution,” Vanui explains. “Fear can be useful—it keeps us alert. This labyrinth helps break the stigma that fear equals weakness.”

Some children refuse to engage. They avoid activities or, if forced to participate, purposely ring every bell. These cases are addressed in one-on-one sessions. Each child has regular private therapy, in addition to daily group sessions. The mix of fun, community, and personalized therapy is working.

More than 500 children have gone through Gen.Camp already. Officially, over 313,000 children in Ukraine have the legal status of war-affected. 1.6 million are living under Russian occupation. 2.1 million school-age children were forced to flee Ukraine. All of them have lost a part of their future—a chance to live the lives they once imagined.

As of 2022, an estimated 75% of all Ukrainian children had experienced war-related trauma. This year alone, hundreds applied to Gen.Camp—but only 50 can attend each session.

Drawing out the fear

One evening at camp, the kids gather for a round of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? The questions range from basic trivia—What’s the largest country in Europe? (It’s Ukraine) or How many legs a spider has (eight)—to trickier brain teasers like: Which month has 28 days? (All of them).

The prize is genchiks: the camp’s own currency, earned through knowledge, effort, or kindness. By the end of the session, genchiks can be spent on rewards—extra swim time, a late-night movie, or even the right to douse counselors with icy water.

The room is loud and full of energy. Kids are shouting answers, laughing, and arguing over which insect has the most legs. But off to the side, on a nearby table, is a quieter reminder of why they’re really here: drawings of fear.

Each picture is part of another therapeutic exercise—children are asked to draw what frightens them most.

“I drew death and war. That’s my biggest fear,” says 17-year-old Valeriia. “During any attack, a drone or a missile could kill you. I also drew the future—because I’m scared of what’s coming.”

Valeriia is the oldest camper. She just began her first year at university, where she studies architectural design. She plays volleyball, and she dances. She also spent eight months under Russian occupation. Her parents helped 50 people escape to Ukrainian-controlled territory. After that, she was terrified of anyone in uniform—even Ukrainian soldiers. Her father later joined the military. He was killed at the front in April 2024.

Some children don’t want to talk about their loss. Others, like 10-year-old Davyd, feel a need to speak.

“My dad was a hero,” he says. “Everyone should know.”

Davyd’s father was a rescue worker with Ukraine’s State Emergency Service.

“It was July 13, 2024,” says the boy. “The enemy launched a missile. Dad went to the scene—they struck again. He saved everyone. Everyone, except himself.”

His father had just enough time to lead his team and nearby civilians to safety, but didn’t make it to the shelter himself. He was posthumously awarded the title Hero of Ukraine. The coffin was closed. Davyd still secretly hopes it was a mistake—that somehow, his dad is still alive.

These types of attacks—known as double-tap strikes—are a Russian military tactic: targeting a site, then hitting it again to kill medics, first responders, and those trying to help. They began doing this in Syria, including Russia’s notorious 2016 attack on Aleppo. In Ukraine, by the end of 2024, more than 60 such strikes had been documented by the human rights group Truth Hounds.

Davyd tells his story with pride. He dreams of becoming a singer and even writes music using AI. He listens to Shakira.

During sports hour, he unloads his anger on a punching bag.

“Guess who I’m picturing? I hate him!” he shouts to his friends.

“Hint: he’s not in Ukraine.”

They all know. The answer comes fast—Putin. Davyd keeps punching, harder and harder.

He’s earned 43 genchiks—an impressive sum. For context, an extra hour at the pool costs 10.

Asked what he’d do with an infinite number of genchiks in real life, he answers without hesitation: “I’d give them all to soldiers and rescuers.”

“I remember the day my dad went to war”

Watching these children play board games or volleyball, scream with joy in the pool, or dance at the Neon Party, it’s easy to forget why they’re here.

But they’re not at camp just because they deserve a childhood—though they do. They’re here because the people who once gave them that childhood—fathers, mothers, siblings—are no longer alive to share it with them.

“I don’t remember when the war started,” says 15-year-old Illia. “No one told me. But I remember the day my dad went to war.”

Illia’s father volunteered to fight. He was killed trying to save a fellow soldier. When the memorial plaque in his honor was unveiled, Illia stood through the entire ceremony with his eyes closed.

“I’ve seen a lot of dads,” he says. “But mine was the best. He always knew how to motivate me. We loved fixing things together, especially this one cabinet that always broke. It still does, but now I fix it alone.”

Illia also remembers watching movies together. “He had this funny way of watching them—he always fell asleep at the best part. In the morning, I’d tease him: you don’t even know what happened! But somehow he always did. I still don’t know how.”

Illia dreams of becoming a basketball player. He’s a fan of the Minnesota Timberwolves, especially Anthony Edwards, and he trains almost every day. If basketball doesn’t work out, he wants to become a prosthetist.

“I saw it in movies and looked it up in real videos,” he says. “At first a person can’t do anything—and then a prosthetist helps them get their life back. They’re so happy in those videos. I want my work to bring that kind of happiness. I want to be remembered. Like my dad.”

The mission of Gen.Camp isn’t to erase grief. It’s to help children remember their loss and still choose life. One day during each session is devoted entirely to remembrance. Campers gather to honor those they’ve lost.

At the appointed hour, little Ivanka leaves behind her orange ukulele and climbs a nearby hill. When she reaches the top, she lights a small candle.

“I want Dad to see better,” she says. “I want him to know that I love him.”

-9a7d8b44d7609033dbc5a7a75b1a734e.jpeg)

-554f0711f15a880af68b2550a739eee4.jpg)

-6ead6a9dd508115a5d69759e48e3cad1.jpg)

-29a1a43aba23f9bb779a1ac8b98d2121.jpeg)