- Category

- Opinion

How Russian Soldiers Can Surrender and Actually Survive: A Step-by-Step Guide

With over 1 million Russian casualties, surrendering through Ukraine’s official program is the only real path to survival—and the only right move left.

Russian military losses have surpassed one million soldiers as of June 12, 2025, since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Statistically speaking, the Russians are losing about 1,100 to 1,300 soldiers per day. In practice—given that Russia’s main tactic relies on relentless meatgrinder assaults with little regard for casualties—this means that for nearly every Russian soldier sent to the front, death or serious injury is virtually guaranteed.

Add to this the widespread practice of summary executions—known as “obnuleniye”—carried out against comrades who refuse to take part in assaults, surrendering to Ukraine’s Armed Forces is often the only way for a Russian soldier to preserve their life.

While the Russian state knowingly drives its people into a slaughterhouse, Ukraine offers them a chance to live and “break free from the war machine.”

How can a Russian soldier surrender?

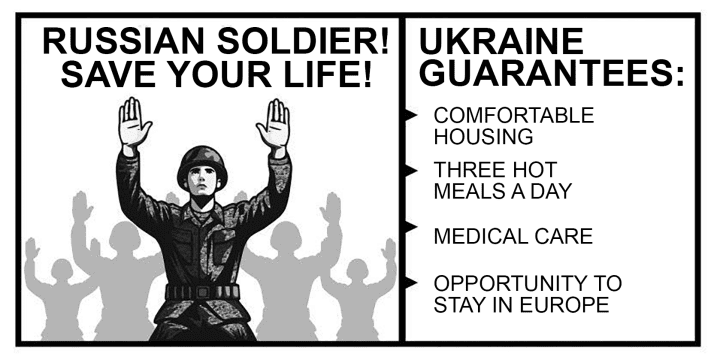

As difficult as it may sound in wartime conditions, seizing that opportunity is relatively straightforward. Calls to surrender are literally dropped on the Russian soldiers in the form of leaflets. These flyers typically instruct them to raise their hands or wave a white flag. Increasingly common now are instructions on how to surrender to a drone—a method well-suited to modern battlefield conditions.

Ukrainian troops don’t need additional motivation to take Russian soldiers prisoner. They understand that every new captive can contribute to the exchange pool, helping bring Ukrainian captives home from Russian torture chambers. What’s more, even in such a brutal war, Ukrainians continue to uphold a basic sense of humanity.

Another path to laying down arms is through a dedicated Ukrainian government project called I Want to Live, which operates 24/7 and accepts voluntary surrender requests from Russian troops.

Why is there a dedicated hotline for surrendering Russian soldiers? First, surrendering on the battlefield is inherently dangerous. There’s always a risk of getting hit by stray fire or shrapnel. Voluntarily surrendering while surrounded by Russian soldiers is even more dangerous—Russian propaganda brands surrender as betrayal, and traitors in the Russian Armed Forces are often executed. Numerous documented cases confirm that Russians have killed fellow soldiers attempting to surrender or who had already surrendered.

Contacting “I Want to Live”—via phone call, messaging apps, or chatbot—helps minimize those risks. Specialists prepare and coordinate the handover operation, making the process as safe as possible.

Second, not only can frontline soldiers contact the program, but rear-echelon personnel and those facing mobilization can as well. The project was originally created to help Russians avoid the partial mobilization announced by the Russian leader, Vladimir Putin, functioning as a preventive measure. That role remains relevant to this day.

What are the benefits of surrendering through “I Want to Live” or entering Ukrainian captivity?

Beyond the obvious—staying alive—the project gives Russian servicemen a chance to choose their future. Those who surrender can remain safely in captivity until the end of hostilities. Afterward, they may seek asylum in a European country or return to Russia.

Ukraine also guarantees confidentiality. No commanding officer will know that a particular soldier voluntarily surrendered via “I Want to Live.” This anonymity is deeply valued—many fear exposure more than anything. On paper, it will appear as though the soldier was captured in combat or against his will. His family will continue receiving state payments and will not face persecution.

Being a prisoner of war (POW) in Ukraine is significantly safer for a Russian soldier than remaining in the ranks of the Russian military. Ukraine abides by international humanitarian law. Conditions in Ukrainian POW camps are as humane as possible. There is no abuse, no summary executions. In fact, Russian POWs can even earn modest wages for light labor—no less than eight Swiss francs ($10) a month, as stipulated by the Geneva Conventions.

Russian surrender by the numbers

In nearly three years of operation, the “I Want to Live” project has received over 47,000 applications from Russians. The number of individuals who have voluntarily surrendered through the program exceeds 400.

It’s important to understand that just raising your hands or waving a white flag isn’t enough. Every evacuation of a Russian soldier who contacts the project is a complex special operation that takes careful planning and time. Crossing the front line is never 100% safe, but Ukrainian specialists do everything possible to minimize the risks. So far, every evacuation attempt has been carried out successfully.

The best way for Russian troops to stay alive is to surrender. Ukrainian forces take Russian soldiers who chose life. pic.twitter.com/f7szlic1Te

— UNITED24 Media (@United24media) March 3, 2025

The project has also become a tool of counter-propaganda and an important channel of communication with the Russian population on the issue of prisoners of war.

Is “I Want to Live” only for Russian citizens?

In the past year, the number of foreign mercenaries in the Russian army has risen sharply. Russia has established a large-scale global recruitment network targeting the war in Ukraine. Most of those recruited come from impoverished countries in the Global South or nations once part of the Soviet Union. Many are coerced into joining—lured by promises of well-paying jobs or forced to sign contracts under threat.

As of mid-2025, citizens of 33 countries are being held as POWs in Ukraine. Last fall, Ukraine’s Foreign Affairs Ministry called on all foreign nationals to avoid serving in the Russian military at all costs and, if sent to the front, to contact “I Want to Live.” The project’s website includes English and Spanish versions specifically for foreign audiences.

Ukrainian citizens conscripted by the Russians from temporarily occupied territories can also use the program. Provided they haven’t committed crimes against Ukraine, they are not considered traitors but victims of a war crime under the Third Geneva Convention.

To Russia, POWs are just another weapon to use against Ukraine. Since 2014, Russia has used them as bargaining chips and tools of psychological pressure on Ukraine and its society. It’s essential to keep this in mind and not fall for Russian propaganda about prisoners of war. Rely only on official sources—first and foremost, Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters for the Treatment of Prisoners of War.

-1431a66f1b13d892705a77a1a89702a5.jpg)

-7e242083f5785997129e0d20886add10.jpg)

-657d7bbeba9a445585e9a1f4bccfb076.jpg)

-c48eebd28583d39a724921453048d33f.jpg)

-56360f669cb982418f455a4b71d34e4e.jpeg)